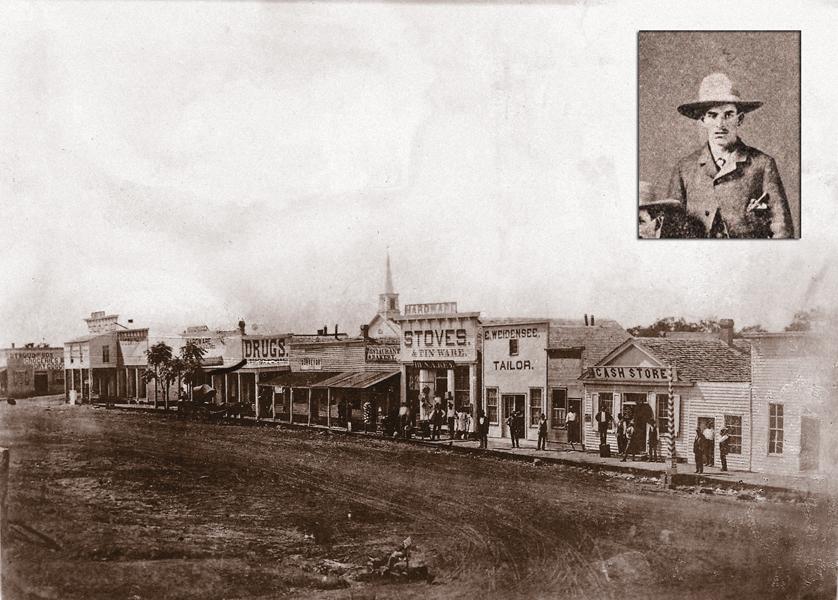

No one would call this Texas robber a criminal mastermind, despite the legend that often trails his name.

One stagecoach holdup netted about $38, while the take from an 1878 train robbery totaled just over $600. Hell, the robber didn’t even lead the infamous 1877 raid on a Union Pacific train in Nebraska, which garnered more than $60,000. His freighting partner, Joel Collins, actually did; but since it is still the single largest robbery of the Union Pacific, it makes sense that it launched the 26-year-old Sam Bass to fame.

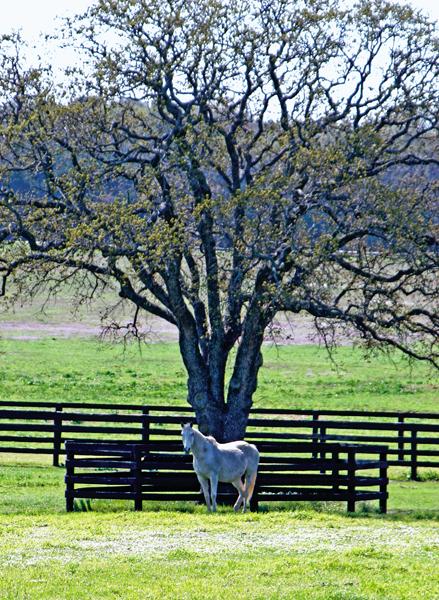

Sam did have an eye for horseflesh though, especially horseflesh that ran fast. He proved the point in the fall of 1874.

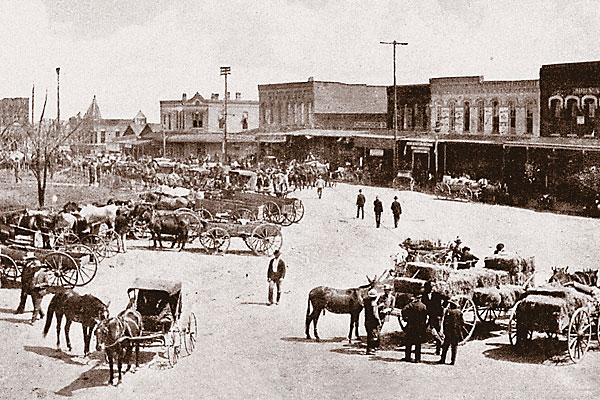

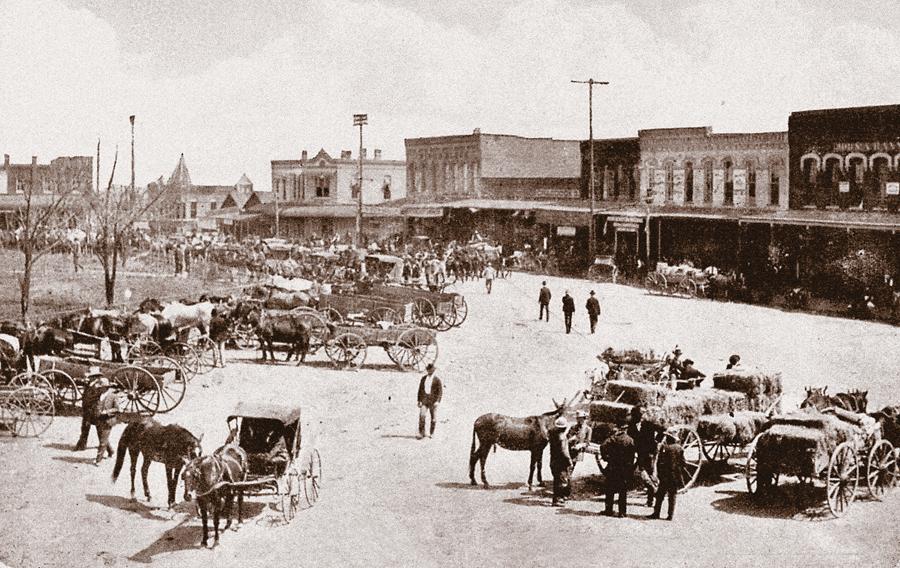

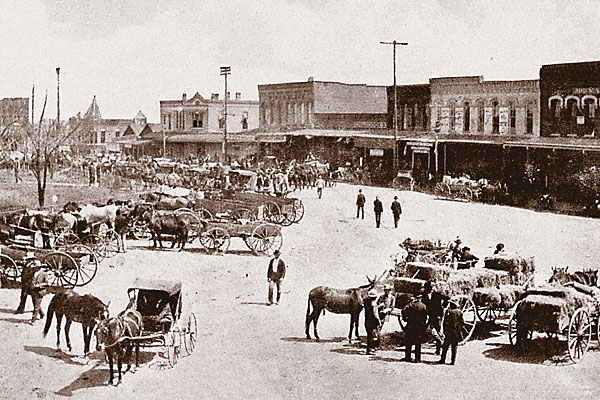

Bass was living near the town of Denton, about 35 miles north of Fort Worth, working odd jobs here and there. He also owned four horses, perhaps for use in some freighting work. Sam got interested in “scrub races,” one-on-one horse sprints over improvised quarter mile, straight-ahead tracks. These social affairs were well-attended, attracting dozens of onlookers—and plenty of betting money. Bass wanted a piece of the action. He spotted a two-year-old gray mare named Jennie, a speedy animal bred in the Denton area, and quickly bought her. With the skinny black jockey Charlie Tucker aboard, Jennie began winning races.

In fact, the Bass stable was doing so well that Sam began taking Jennie across Texas. Folks started calling her the “Denton Mare.” Even today, she is one of the best-known horses in North Texas history.

That says a lot. For the Denton County horse industry was up and running long before Sam Bass came around (and long after he was gone).

A History of Horses

Cattle ranches dominated the scene in Denton as far back as the 1850s. Ranchers needed horses, of course, so they either had to buy them from somebody else or grow their own, as it were. John Chisum—who later became famous for his role in New Mexico’s Lincoln County War—was one of the top ranchers just prior to the Civil War. By 1860, he claimed about 6,000 of the 20,000 cattle in Denton County, and he bred his own Spanish cow ponies to help run the herd. His neighbor William Wright went a step further—he bought some Spanish mares in Mexico and started the first horse ranch in north Texas.

The Civil War disrupted Denton during the 1860s. The livestock operations struggled as many animals went toward the Confederate war effort. Men like Chisum moved farther west, to New Mexico and Arizona. The cattle industry did a free fall; by 1920, only about 12,000 head remained in the county. The region’s economy fell back on agriculture—cotton, wheat, even some peanuts. In the 1960s, the town of Denton grew as a bedroom suburb to the metroplex of Dallas/Fort Worth.

Yet Denton’s past was about to come charging forward.

Come the Horsemen

In the early 1970s, a handful of horsemen saw the possibilities in Denton County. Its soil composition is a sandy loam, which allows quick absorption and runoff of water—standing water can cause physical problems and illness for horses. The climate is favorable, with January lows averaging 34 degrees and the average July highs hitting the mid-90s. And north Texas land is a lot cheaper than the bluegrass of Kentucky, making it attractive to folks with limited budgets. So when traditional farms started struggling in the 1970s—many went under, while others were forced to sell for whatever they could get—ranchers picked up large tracts at bargain-basement prices.

They saved money in one area, but spent it somewhere else. Breeding, raising and training horses is a big bucks endeavor. An operation needs barns, training space, fencing, laboratories and medical facilities, qualified workers and, of course, horses. Today, smaller operations need an initial outlay of more than a million dollars to get things going. By contrast, Sam Bass paid about $250 for the Denton Mare, and probably boarded her and his other horses for just pennies a day.

Cost hasn’t hindered the growth of the north Texas industry. More than 300 horse operations, with a total of about 25,000 animals, flourish in Denton County. Horse sales in 2004, the last year surveyed, totaled more than $20 million. Boarding fees alone topped $11 million. This is big business, even in Texas, where “big” is a lifestyle and heritage.

Some of these ranches are just small “mom and pop” setups that handle just a handful of horses. Others are multi-million dollar operations that board horses for other owners, as well as breed and train animals for pleasure or competition.

The modern horse operation is into specialization. A ranch or farm usually emphasizes a particular breed, whether it be Thoroughbred, Quarter Horse, Paint, Andalusian or any number of others. Then the horses are trained for specific disciplines—racing, jumping, hunting, cutting and many more. John Chisum’s lessons aren’t forgotten here; Spanish cow ponies are still bred for ranch work.

Thoroughly Modern Ranching

If John Chisum or Sam Bass came back and toured the modern horse operations in Denton County, some sights would be familiar. Others would leave them scratching their heads.

They would still see barns with stalls, and horses.

But the cowboys are not always boys. Visit the McQuay Stables, for example, and some of the riders are women. All are college educated. Some are from Europe. And there’s nary a cowboy hat in sight—most everybody wears a baseball cap.

At places like Star Gate Ranch, the riders exercise the horses in huge, covered amphitheaters—complete with seating for visitors. And each exercise session is planned for the individual animal. Horse trainers at larger operations ride sometimes up to 11 hours per day.

Bass would probably be shocked at the number of veterinarians. Most ranches have at least one on retainer, ready to come at a moment’s notice. A handful actually have vets on staff, living on or near the facilities. They practice preventive medicine, trying to avoid illnesses or diseases that could damage or kill a horse. They harvest a mare’s eggs, acquire a stud’s semen, create life in the test tube and implant embryos. They help mares give birth and keep a close eye on each baby during its first few days on earth. Their laboratories—many just down from the stalls—are high tech and cutting edge. After all, if you’re dealing with a horse worth tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars—and who might sire animals worth millions—you want everything just right.

The other striking feature is that the facilities are incredibly clean. Sure, they have to muck stalls, and that hasn’t changed in centuries. But the barn floors you’ll see around Denton are made of special materials that are easy on the horse and easy to keep spit-shine fresh (well, almost). Outdoor walkways, paths, roads and even the pastures are also beautifully kept. Sure, some of it is for the appearance sake. But a clean environment also makes for a healthier horse. And a healthy horse is a more valuable horse.

Love of the Game

Okay, so we’ve established this is a business. Big business. Big bucks.

But there’s something underlying that.

Take Norm Van Sloun, who helps oversee operations at McQuay Stables (his son-in-law owns the place). He’ll take you on a tour of the stables, and he can tell you everything about each animal—parents, children, health, competition record, you name it. And the horses know him, greeting him as he approaches their stalls or outdoor enclosures. They know he’ll probably have some treat in a pocket, a kind word and a pat on the head. There’s genuine affection going on here.

The folks who work at the ranches—from the guy who mucks the stalls to the millionaire owner—love horses. Plain and simple. They love to be around the sights and sounds and smells of horses, to watch these magnificent creatures at exercise or at ease.

It’s easy to see how folks like Sam Bass could be so attracted to horses—not just to the race winnings, but also to the animals themselves.

Bass Ackwards

Back to our soon-to-be wayward hero, Sam Bass. Bass and Co. ran the Denton mare for a couple of years—and then she’s lost to history. Maybe Sam sold her. Maybe he lost her to a bet. Or maybe she was collateral for some mounting debts as the young man felt his oats, falling deeper and deeper into a lifestyle of wine, women and song.

What is known is that by the summer of 1876, Sam was hanging out with some shady characters, engaging in various schemes to fleece poor suckers. More often than not, the frauds involved horses and gambling. In less than a year, he and his pals were robbing stagecoaches in the Dakotas. And he never looked back.

Sam Bass met his end in Round Rock, Texas, in July 1878. He and his gang members walked into a trap as they prepared to hold up a bank. Ironically—or not—Sam took a fatal bullet in the back as he was mounting his horse, trying to get the hell out of Dodge. He died the next day, July 21, his 27th birthday.

Even to this day, folks up in Denton still have fond stories to tell of Sam Bass—and of Jennie, the Denton Mare, the filly that was several historical steps ahead of the booming horse industry that dominates the landscape of Denton County today.

Photo Gallery

– By Nadine VerStandig –

– By Nadine VerStandig –

– By Nadine VerStandig –

– All photos courtesy Denton County Historical Society unless otherwise noted –