America was celebrating its centennial when word came of George Custer’s destruction by the Lakota Sioux at the Little Big Horn (Northern Cheyennes and Arapahos also fought troops in that battle). A devastated nation demanded punishment. Humiliated by the obliteration of the command, the U.S. Army wanted revenge.

America was celebrating its centennial when word came of George Custer’s destruction by the Lakota Sioux at the Little Big Horn (Northern Cheyennes and Arapahos also fought troops in that battle). A devastated nation demanded punishment. Humiliated by the obliteration of the command, the U.S. Army wanted revenge.

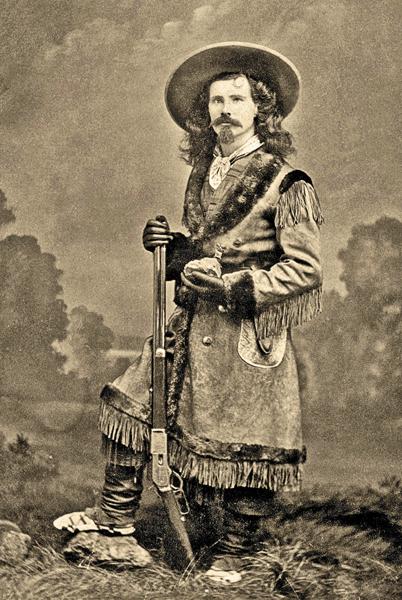

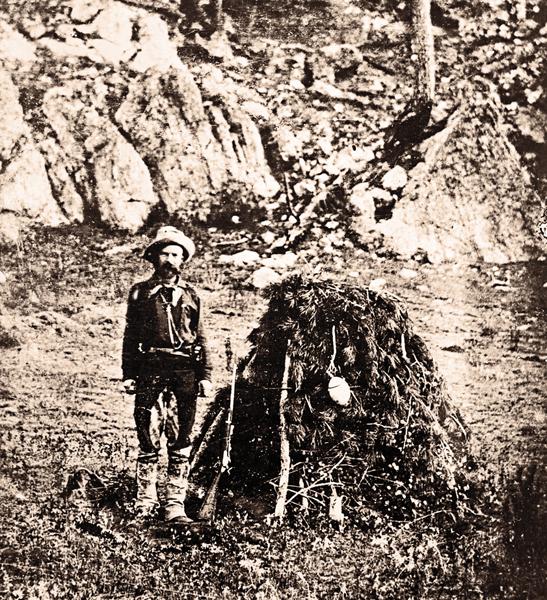

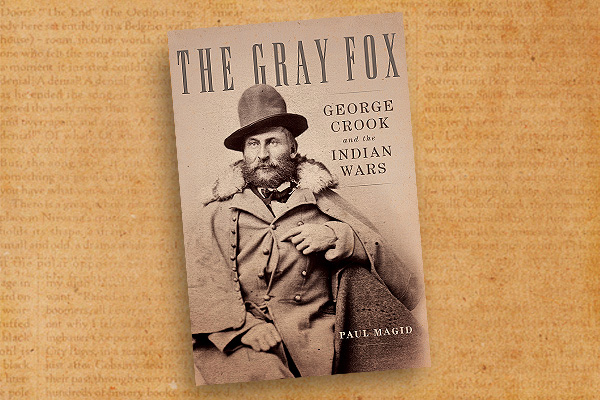

General George Crook believed the only way to end the war was to catch the Indians while a tribe was still in one large gathering before the various bands drifted apart. Crook had 1,500 cavalry, 450 infantry, 240 Indian scouts (mostly Arikaras) and 44 white scouts and packers the likes of Captain Jack Crawford, Frank Grouard and Charles “Buffalo Chips” White.

On August 25, 1876, Crook struck out for the Little Missouri River from the Powder River, covering a distance of some 400 miles. He had only 15 days worth of rations, and he had made no arrangements to be resupplied.

Revenge for Custer

The general ignored the many Indian trails leading south. He had one goal in mind—hit a large village before the tribes dispersed. He would let his ration problem “take care of itself.”

Crook did not know the Sioux were already breaking up. Hunkpapa and Santee Sioux had crossed the Missouri River at Wolf Point, about 40 miles below Fort Peck, for Canada.

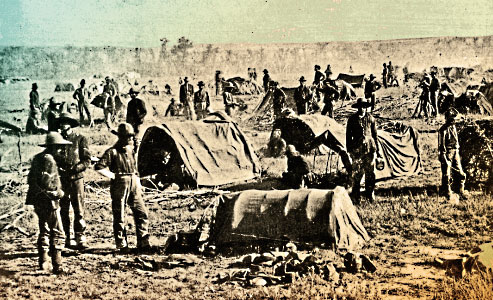

By September 5, Crook’s column was on half rations. Winter storms continued to sweep in. Cold rain and hail unwaveringly pelted the hungry troops on their line of march. For a week and a half, beginning on September 4, they found themselves trudging through a sea of gumbo mud that acted as glue on everything. When it wasn’t raining, the column marched through the muck in a dense fog.

On September 7, the day before his birthday, Crook sent his last Arikara scout to Fort Abraham Lincoln with dispatches. The only troops who knew the territory well were the Arikaras. The command now was at the mercy of Crook’s compass and crude maps of the area.

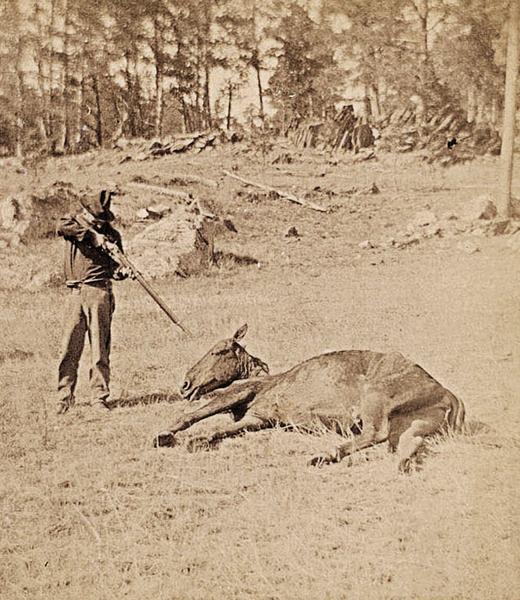

The weary and starving men deliberately began falling to the back of the column so they could kill a horse or mule, slicing the animals up and eating the meat raw.

Ration Reality

“General Crook ought to be hung [sic],” Col. Eugene Carr overheard an orderly say, when soldiers began killing the animals in full view of everyone.

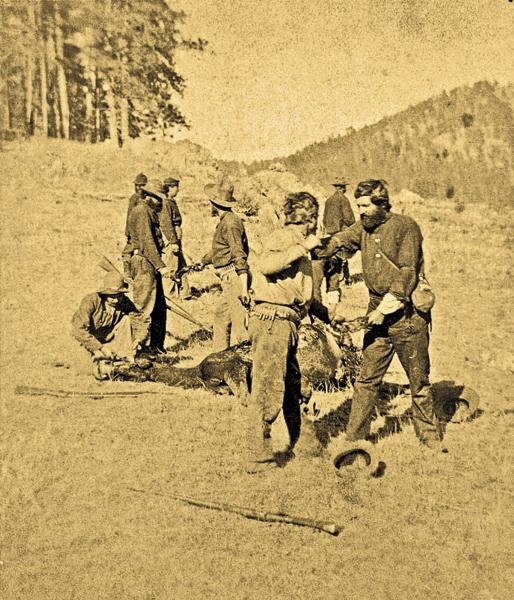

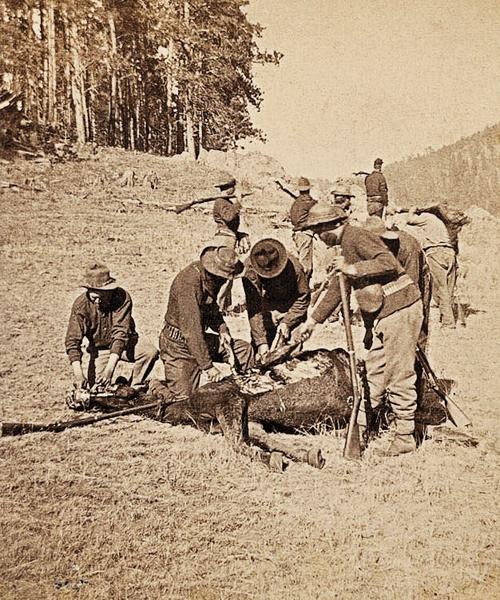

Crook finally accepted the failure of his plan. He gave the go-ahead for the camp cooks to shoot and butcher the worst of the mounts. All the men were to have horse meat.

Thinking he was not going to make it at the men’s current pace, Crook sent a flying column with 150 mounted men ahead for Deadwood, Dakota Territory, to bring back food. Captain Anson Mills escorted the flying column, while Crook’s chief of the commissary, Lt. John W. Bubb, took charge of 16 packers and 61 pack mules. Grouard and Crawford were assigned as scouts. The men pulled out on September 7.

On the evening of September 8, Grouard spotted a Sioux pony herd, just ahead of the flying column, at a place called Slim Buttes, near present-day Reva, South Dakota. On the other side of the rise was a small Sioux village.

Mills called for an officers’ conference. Though their mission was to bring back food, they had an opportunity to strike the first blow since the Custer fight. Without sending word back to Crook, Mills decided to strike at dawn.

The captain divided his command into three groups. Two groups were to bracket the village, while Lt. Frederick Schwatka and 25 cavalry troops charged into the heart of the village, shooting their way through and then joining the troops on the other side to hold the hostiles in check. But the troops spooked the Indian pony herd. With horses running into the village, Schwatka had no choice but to charge before the others were in position.

Sioux warriors slashed their way out of their tipis, tied down tightly, due to the winter cold. They guided their women and children to safety, while they returned fire.

With his plan of attack in shatters, Mills hurriedly sent couriers riding hard for Crook. The Sioux were rallying and carefully advancing on him. Mills countered with charges of his own, until a Sioux bullet took out the knee of one of the leaders, Lt. Adolphus von Leuttwitz.

Mills dug in just outside the lodges. The Sioux warriors did the same, on the bluffs overlooking the village.

“No Quarter!”

As the sun rose over the hills, Mills sent a patrol into the village. In a matter of minutes, a Sioux sniper hidden in a ravine shot one trooper directly in the head. Mills tried smoking out the sniper, only to have three more soldiers wounded. With one dead and five wounded, he called back the patrols and waited for Crook.

The main column rode in piecemeal until Crook’s entire force was before the village by 2 p.m. The general tongue lashed Mills for not sending word of his proposed attack. Crook then ordered the sniper taken out.

The men, however, soon discovered that more than one warrior lay hidden in the ravine. A deadly firefight opened up, with both legs of one trooper broken by a single shot. “Buffalo Chips” White tried to locate the shooter, only to take a bullet in the heart.

Crook ordered a skirmish line firing repeated heavy volleys into the ravine. When Sioux women and children ran out of the gulley, the general persuaded one woman to get the others to surrender.

To everyone’s shock, only the tall Chief American Horse and one other warrior stepped out. American Horse stood erect, but he was holding his side, trying to keep his entrails from spilling out.

Crook’s troops shouted, “No quarter!” They knew American Horse had been in the Custer fight, and that he had personally slit the throat of Lt. William Fetterman 10 years earlier along the Bozeman Trail.

Crook, though, was impressed with American Horse’s bravery. He asked the surgeon to tend to the chief, but nothing could be done. The famed warrior died a few hours later.

While most of Crooks’ men were busy flushing out the Sioux snipers, some found horses, saddles, clothing and a guidon with 7th Cavalry markings from the Custer battle.

When these starving men discovered piles of dried buffalo meat, Crook lost control. The men gorged themselves and then napped from exhaustion. Many of his men had walked to the site because their animals were eaten during the march. Crook himself seemed confused. He posted no sentries and sent out no scouts. His Army seemed to have finally reached the limits of its endurance.

Crazy Horse’s Charge

Four hours later, the bluffs around Crook’s men erupted in gunfire. Swarms of warriors, led boldly by Crazy Horse, poured over the landscape. Crazy Horse was leading only 300 against Crook’s 2,000, but the fury of the Sioux forced the general to place every man he had into the fight. The onslaught was a series of charges and countercharges. Darkness ended the battle. Remarkably, no troopers were killed in the engagement.

The entire point of Crook’s march was to engage a large body of Sioux and thoroughly defeat them. He finally met the enemy, but Crook found his men too exhausted to destroy his adversary.

All through the night, the Sioux pressed the perimeter. The popping sound of gunfire in the dark kept the men awake and keyed up. Crook had to get his men out. They were no longer in any condition to fight. His men had devoured the tons of captured food so rapidly that Crook placed a guard on reserve for the ill and wounded.

As dawn approached on September 10, Crook sent four companies of infantry to hold back Crazy Horse. He then prepared his column for the march. Crook pulled out at 8 a.m. When he did, the Sioux swarmed in from all directions, determined to wipe out the rear guard commanded by Col. Carr. Carr’s energetic handling by revolving troop placement saved his men from being massacred during the moving two-mile fight.

Crazy Horse and his Sioux eventually retired from the fight, and Crook’s men continued their slow march for Deadwood—again without provisions.

Two days later, Crook’s army fell apart.

The Storm Before the Calm

Although they had lost the Sioux warriors and were on track to reach much needed food and supplies, September 12 was not a good day.

Officers could no longer keep discipline. Rain returned. The horses dropped like flies. The column was scattered over the landscape, refusing or unable to form up. Men piled up their saddles and hid the ammunition, refusing to carry it. Many dropped in the mud, sleeping where they fell. Schwatka wrote that Crook’s army appeared strung out for 10 miles.

For three days, the column was physically unable to advance. Then word came that relief wagons had just crossed the Belle Fourche River, heading toward them.

The scarecrow soldiers stood up and marched for the wagons. They reached them in the afternoon, just as the sun broke through scattered clouds. Crook’s men cooked well into the night, waking up suffering from diarrhea, but alive.

They had marched more than 400 miles while starving. Even more, these courageous soldiers had engaged the Sioux in three pitched battles, lost a few men and gotten out of it alive.

Crook proclaimed victory.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.

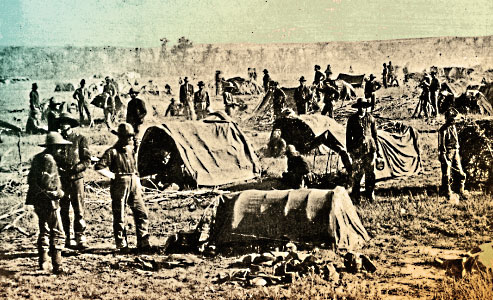

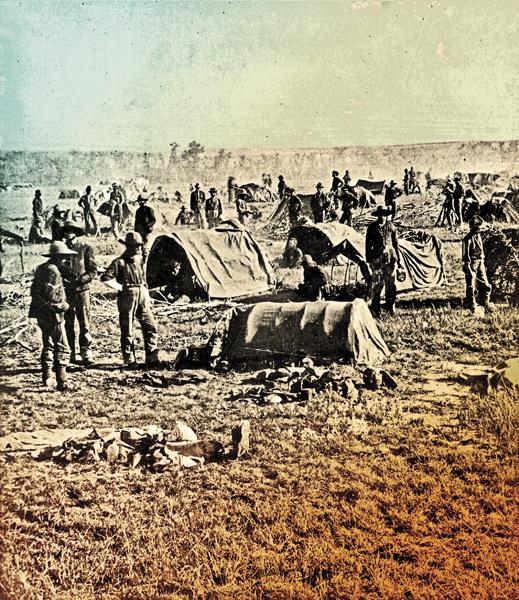

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –