Some 30,000 pictures ago, Gil Gustavsen and Cheryl Stapleton thought they were going in a totally different direction.

Both transplants to Arizona, they teamed up to sell photographs of beautiful Sonoran desert scenes and plant life, and of the Grand Canyon.

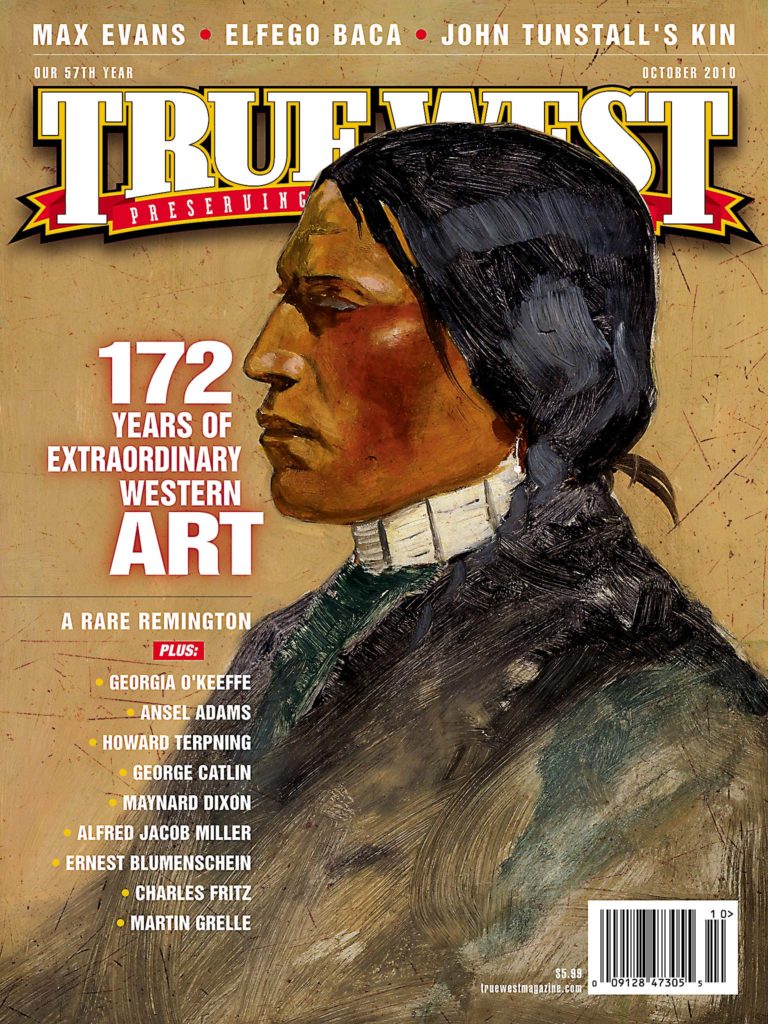

Then, in 2005, they met Bob Boze Bell of True West magazine, “and our entire focus changed,” Stapleton remembers.

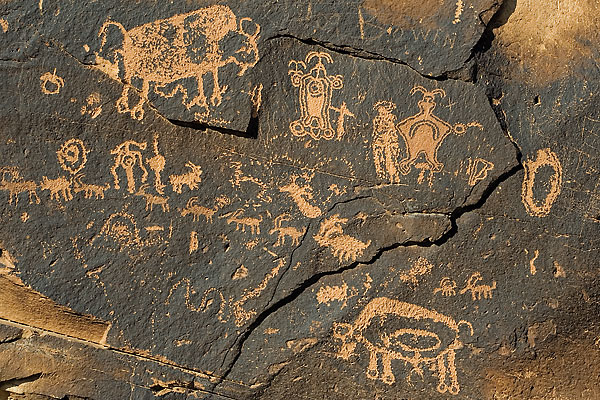

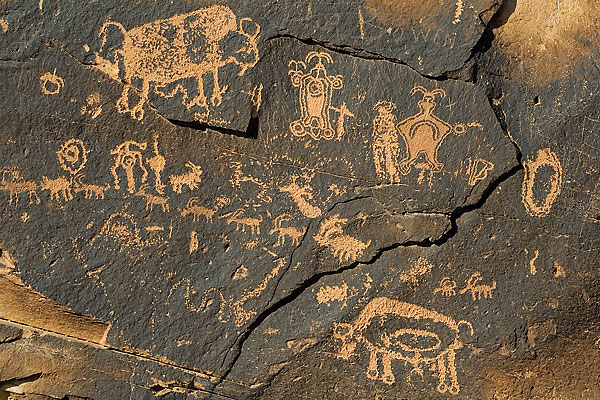

Today, their Gustavsen-Stapleton Studios in New River, Arizona, is known for its extensive photography of prehistoric ruins. They sell their art online and at art fairs in the Phoenix area, and they’ve become experts about Hohokam and Anasazi ruins in Arizona, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico.

Their journey of discovery started pretty badly, actually.

Hoping to get some photographic work with True West, they visited the Cave Creek office to show off their portfolio of modern desert scenes.

“Bob liked our work and said he was working on an editorial on petroglyphs and needed pictures of vandalism,” Gustavsen remembers. “We wouldn’t normally have photographed that, but we went looking.”

They went to South Mountain Park, Camp Verde, White Tank Mountains and other sites, and “thankfully, we didn’t find any vandalism,” Gustavsen remembers. They didn’t want to go back empty handed, so, as a joke, Gustavsen says they photoshopped a “counterfeit” picture of a rock wall with red spray paint that read “I love Bob.”

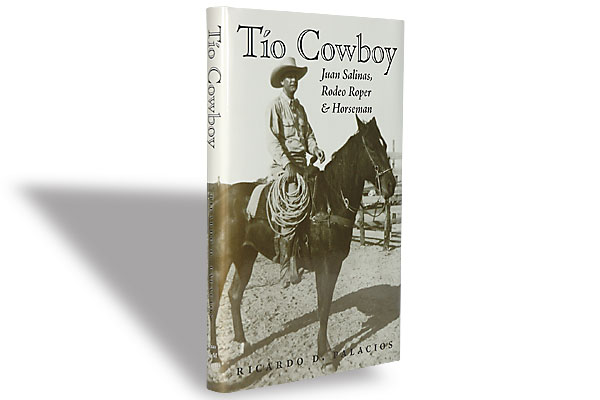

Bob loved their tenacity and put them on the trail of what would become their first of many prehistoric ruins—the remarkably pristine Range Creek Ranch near Price, Utah. But Bell warned them they might have difficulty, because the crotchety cowboy who owned the ranch didn’t like anyone trampling around his 42,000 acres. That’s how the pair met Waldo Wilcox and how the rest of their lives began.

“Waldo had a reputation of running everyone out of his valley,” Gustavsen says. Waldo’s father had bought the Range Creek Ranch in 1952. It had Fremont Indian pots lying on the ground, a granary that still had grain and untold number of petroglyphs.

“Waldo’s father took him and his brother around the ranch when they were little, and told them, ‘Leave these things alone.’ The boys did as they were told,” Gustavsen says.

That’s how Utah officials, who were “blown away” by the untouched artifacts, found the site when Waldo decided to sell it as he reached his 70s. The state bought the ranch, put it under the control of the Game and Fish Department and archaeologists began cataloging the artifacts.

Waldo wasn’t interested in being interviewed, yet he said he’d give the photographers an hour of his time. “He loved Cheryl, and our one hour turned into three days,” Gustavsen says. “It was like meeting Butch and Sundance for me.”

One of the first facts they learned about America’s prehistoric sites scares them to this day: “There’s nobody out there protecting these sites,” Gustavsen says. “The only reason most of them are still here is that nobody knows where they are—some of our pictures, we won’t even identify the exact location in order to keep them protected.” He notes they “photograph everything” because these sites could be destroyed. “We want to get it before it’s gone,” he says.

The 56-year-old Gustavsen, who used to make custom furniture when he moved to Arizona from New Jersey, admits it is physically hard work to reach many of the remote spots where the ruins are located, but the strain is worth the effort. “I personally find [Indians] absolutely fascinating. I’m learning about the cultures and their artwork.”

For the 50-year-old Stapleton, a former Cape Cod journalist and photographer, the quest is in imagining how people lived. “We learn by seeing,” she says. “There aren’t blueprints or diaries to tell us how they built and how they lived, so we can only guess. Imagine living 200-300 feet up a cliff wall—the men are out hunting and the women have to get water every day way down in that stream. They have to keep the fires going; they have to keep the kids from falling off the cliff. I have a great regard for the women—it couldn’t have been easy.”

The pair’s photographs are making a record of the ruins that will hopefully last forever. Visit the website Gustavsen-Stapleton.com to view some of the fine art photography taken by these Old West Saviors.