The Rounders was Director and Screenwriter Burt Kennedy’s first shot at making a Western comedy, and it’s one of his best.

Other movies about aging cowhands and rodeo performers, like Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner, would follow, but The Rounders remains one of the best. At 86, Max Evans is currently celebrating the 50th anniversary of the novel that inspired the film and brought the author all of his initial attention. Published in 1960, his book took a few years to get launched as a film, in 1965, and then, a year later, it became a short-lived TV series, running from 1966-67.

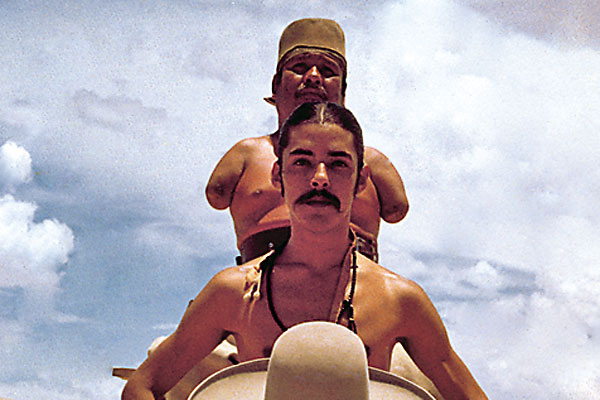

The picture starred Henry Fonda and Glenn Ford as a couple of contemporary broncbusters, Howdy Lewis and Ben Jones, respectively. More than a little busted themselves, the two get hustled into going upcountry for a season to round up strays for a local high-profile hustler named Jim Ed Love (Chill Wills). Along for the ride is a white-faced roan named Old Fooler who seems as smart or smarter than they are, and who won’t be ridden. Lewis and Jones naturally figure they can make a profit betting on Old Fooler at the local rodeo.

A few decades later, in 1998, another Evans novel hit the screen, The Hi-Lo Country. This movie is a companion piece to The Rounders in that it also features Jim Ed Love, this time played by Sam Elliott. It also offered Penelope Cruz her first English-speaking part, and starred Woody Harrelson and Billy Crudup as post-WWII cowhands living in New Mexico.

Max still writes, and he recently supplied a foreword for the anniversary edition of The Rounders. When he’s not writing, he’s had a second career as a painter and some of his work can be found on the Internet.

From his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Max told us, “Goddamn, it’s just a beautiful old day here. I ain’t in jail, and I had a good breakfast. That’s pretty good, you know?”

True West: How long have you lived in Albuquerque?

Max Evans: Been here 43 years. I came out of Taos…. I grew up down in Lea County, and then went to work up on a ranch when I was 11 years old, up on Glorieta Mesa, south of Santa Fe.

Where did you get the urge to write?

I think up on that mesa. The ranch lady there, everybody in that country called her Mother Young. I never did even know her name. She sort of mothered everybody. I cut all the wood and carried her water and helped her dry dishes for her ever’ dern night. She was an amateur painter, and I just loved that. She got the creative bug in everybody one way or another. I think she stirred it up somehow.

She inherited some damn old books. There was some Balzacs there. I always liked to read, and I started readin’ on those damn classics. I didn’t know they were classics. I just loved ’em.

How did The Rounders get made into a picture?

Burt Kennedy discovered it in what they called the “slush pile.” He took it to Fess Parker, ’cause he was so dang famous with that cockeyed show [1955’s Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier], Burt knew he could get it made. Fess jumped right over and took the option himself, instead of Burt—beat him to it. So then, he just dismissed Burt because he got William Wellman to come out of retirement to direct it. Nobody’d been able to get him to come out of retirement.

Old William Wellman loved it so damn much he worked with that cockeyed Tom Blackburn who did all that Disney stuff (Davy Crockett; 1956’s Westward Ho! The Wagons). He worked with him every day, all day on it, and they had a hell of a script. It all blew up over at United Artists within five minutes. The whole thing.

What killed it?

Well, I hate to say it, but the real truth is, Wellman and Fess weren’t seeing anything the same.

Wellman was the finest gentleman who I ever met. He was tough on other people, but if he liked you and respected you, there wasn’t a finer gentleman who ever walked.

When he killed the deal right there, he had the respect to call me out in the hall there and apologize to me, said that he could not work under those conditions with those people. They did not qualify for what he had in mind. He invited me out for a drink, and he’d quit drinking, but I had a half a bottle with him. [Laughs.]

We had a grand time…. He had a punching bag, like the ones tied top and bottom, and he visited with me for 15, 20 minutes, just whammin’ away at that bag. He told me, “I got to where I do this for my health, but in my mind, I’d put the head of a studio right there.” And he’d wham that bag. I loved him from then on.

What did you do after the deal failed?

When the time ran out on [Fess], he very politely took me into town. I wasn’t going to leave until I sold the sonofabitch [book], and he knew about this cheap hotel. I don’t know how the hell he knew about it; maybe he dumped everybody else he’d ever had an experience with there.

Well, old Fess Parker had got me out [to California in the first place]. He gave me a $20 bill, stuck it in my pocket so I couldn’t see what it was. I thought it was $100. I didn’t want to be rude, and I waited till he was gone, and it was a 20. That old hotel was $25 a week. I’d spent all my option money, and Fess knew it.

How did you fare at the hotel?

Well, then I was getting kicked out of the hotel. They threw me and my [suitcase]—at the time I had my suitcase held together with some old binding twine, and I tied it back up, and there I was on the sidewalk.

I went back in to ask if I could make a call. I remembered old Morgan Woodward, the old character actor [1967’s Cool Hand Luke], told me one time at a party if I ever needed him, I could call him. I had the damn number!—couldn’t believe it, still had it—and I didn’t have a dime, couldn’t make a 10¢ phone call. I had to go back in there and literally beg those sonsofbitches who had thrown me out!

They weren’t going to let me call anybody. I finally just talked them into it or threatened them or something, and they let me call old Morgan. It was one of those places—you know they’re gonna tear it down; they just left it running ’til they get ready to tear it down.

So there I was, I just sat down there on that suitcase and waited. He drove up in the biggest, old, black, brand new Lincoln you ever saw. So we loaded my suitcase. That old boy who ran the hotel and his wife are standin’ there, staring out the window at me. I just bowed to them and then crawled into that big ol’, brand new car. [Laughs.]

What happened with The Rounders?

I sold two or three options right off, and old Burt Kennedy came back and put it together.

At the time, not too many directors were making contemporary Westerns, except for The Misfits and Hud.

Yeah, Hud was a hell of a good picture, and I’m not ever gonna put it down.

But… having been raised on cow ranches and worked for as little as $20 a month on those damned old outfits, there was a lot of things in Hud that just didn’t ring true. Rounders is dead on, just like it was….

In this new edition, they insisted, and I mean they insisted hard, that I write a new foreword, explaining what happened to me because of that little old book….

I didn’t want to do it. I said, “It’ll sound like a goddamn telephone book.” And they said, “No, it won’t. Just put the people who The Rounders led you to, who directly had some affect on your life or their life, or somebody….”

That cockeyed little old thing, it led to some of the finest people who I could ever have dreamed. It led to good people like William Wellman, Burt Kennedy was grand and all those kinds of guys. Old Morgan Woodward.

I read a lot of people didn’t like old Glenn Ford, but he was just so wonderful to me. And I made lifelong friends out of old Henry Fonda. We trusted the same old woodcarver and that created a bond between us. And he raised tomatoes, and my wife was a tomato grower, and they hit it off. So we really got along good.

Did you spend a lot of time on that set?

No, I wish I had, on account of old Hank Fonda was painting pictures on that set, watercolors, and they were really good.

I asked him years later about that, how he learned to do watercolors with such finesse. He said, “You know, when I used to work on Broadway, in my later life, I had a tendency to go out and get drunk and hunt women. I got to doin’ it so much, I was afraid I was going to ruin my career, so I took up painting watercolors. I’d get so absorbed, the bars would be all closed and the women would be in bed.” [Laughs.]

There’s a pretty goddamned good plan he had there. It worked, whatever it was, it worked. And he meant that! That was a genuine statement of truth. It was profound to him, and it was to me. Still is.