Alfred Jacob Miller was 27 years old when Scotsman Capt. William Drummond Stewart visited his Baltimore studio in 1837.

Stewart thought his upcoming journey into the American West might be his last. He wanted an artist who could travel with him and record the scenes they would see together.

With strong support from his family and wealthy residents of Baltimore, Miller had freedom to work on his art unhindered with the concern about how to pay his bills. He had traveled to France and Italy in 1832-34, where he viewed—and in some cases copied—paintings by Old Masters. He was already adept at sketches and portraiture, and had moved on to painting landscapes by the time Stewart met him.

After some discussion, the two decided to set off in the spring of 1837 from Independence, Missouri, heading for the fur traders’ rendezvous that would occur on the Green River in what would become western Wyoming.

While most of the fur trade journeys originated in St. Louis, Stewart and Miller jumped off from Independence. The route they took would later be used by travelers to Oregon Country over the Oregon Trail.

Miller & Moses in Missouri

Start your journey by learning about other early overland journeys into the West that were similar to Miller’s. The National Frontier Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri, offers exhibits related to even earlier Western explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, plus details about the rise in beaver trapping and the fur trade, and about overland emigrant travel.

While in Independence, head to the Missouri River Overlook (the National Frontier Trails Museum offers a handy map), at the former location of Wayne City. Situated north of Kentucky Road on River Road in Independence, the Wayne City Landing (also called Independence Landing) saw thousands of emigrants embark on their own journeys west on the trails to Oregon and California. Here, too, tons of goods were unloaded from steamboats and transferred to wagons for transport over the Santa Fe Trail.

In 1849 Pardon Dexter Tiffany wrote to his wife from Wayne City Landing, “After waiting several hours in the rain we got an open waggon [sic] to go up to Independence in and arrived there about dark.” After sleeping on a “very dirty straw pallet” at the Noland house, Tiffany didn’t have much good to say about Independence, noting, “All the day Saturday it rained and the streets are so muddy you cannot get about.”

That same year, a man died of typhoid fever in Independence; Moses Harris was his name. Among his many adventures, he, in 1836, guided Marcus and Narcissa Whitman as far as the Green River Rendez-vous, during part of their trip to Oregon.

Miller featured Harris and another trapper fleeing on horseback from the Indians in a painting of his titled Escape from Blackfeet, commissioned by William Walters in 1858-59 and housed at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. The artist’s handwritten caption for the watercolor includes this statement: “This Black Harris always created a sensation at the camp fire, being a capital raconteur, and having had as many perilous adventures as any man probably in the mountains. He was of wiry form, made up of bone and muscle, with a face apparently composed of tan leather and whip cord, finished off with a peculiar blue-black tint, as if gunpowder had been burnt into his face.”

Those Troublesome Pawnees

When Miller traveled through what is today Kansas, he encountered Indian tribes that had been relocated here during the period of Indian removal beginning in 1825. To get to this part of the country from Independence, you should drive west on Interstate 70 through Kansas City, cross the Missouri River and head to Topeka, Kansas. Then turn north on U.S. 75 to U.S. 36, which you take west.

You’ll be stopping in Republic, eight miles north of U.S. 36 on Kansas Highway 266, where you’ll find the Pawnee Indian Museum State Historic Site. An earth lodge dating to the 1820s is a focal point here. This museum shares the stories and culture of the Pawnee Indian Nation that dominated the central plains long before Miller ventured into the area. Its interpretive trail weaves through the area that once held more earth lodges.

Among Miller’s works is his drawing of Pawnee Indians watching the caravan. The artist once wrote, “Of all the Indian tribes, I think the Pawnees gave us the most trouble.”

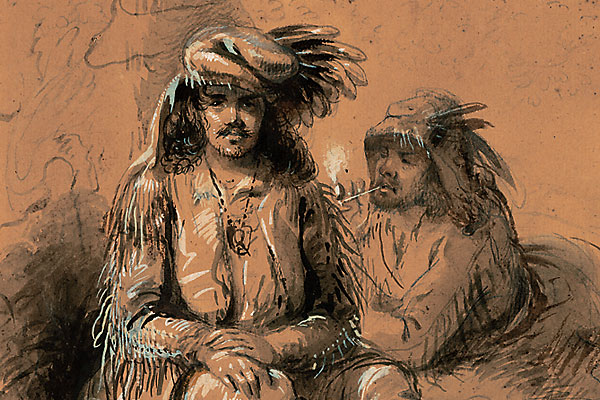

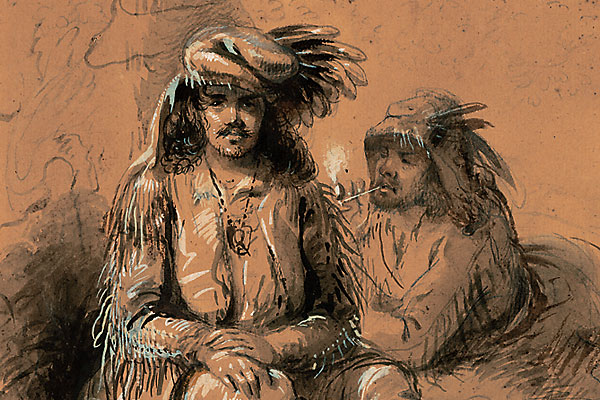

Miller created paintings of Pawnee Indians, such as Pawnee Indian Camp, currently touring the country as part of the Bank of America collection featuring Miller’s artwork. He also left behind stunning portraits of American Indians: Ma-wo-ma (Little Chief); A Young Woman of the Flathead Tribe; and Sioux Indians at a Grave among them. The watercolor, gouache and graphite image he did of his benefactor, Sir William Drummond Stewart and Antoine (identified as a Canadian Half-Breed), is in the Gilcrease Museum’s collection in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Crossing Nebraska

The Platte River, Chimney Rock, Scotts Bluff are all Nebraska sites that Miller captured in his colorful watercolors.

Before you head out to these sites, though, you’ll want to make a stop at Minden. You can get there from Republic by backtracking to U.S. 81, following it north into Nebraska to Hebron and turning west on U.S. 136. Then follow that highway through Red Cloud to Franklin, and head north on Highway 10 to get to Minden, home to Pioneer Village.

This is one of those sites that has so much to see, you won’t be able to take it all in on a single visit. The collections range from small items, such as matchbooks or pens, to train engines, airplanes and wagons. The buildings are packed with artifacts and memorabilia that take you on a trip through time from the period when Miller would have been in the region to more recent days.

After your adventure in Minden, head north on Highway 10 and then west on Highway 50A to Fort Kearny, located south of the Platte River near the city of Kearney. Not established until more than a decade after Miller and Stewart were here, Fort Kearny became one of the most important trail outposts, serving people who had jumped off from many towns along the Missouri River. The eastern end of the Oregon Trail between the Missouri and Fort Kearny is like a frayed rope with many strands leading to the point where the rope is knotted; from here on west you’ll find one main trail, though, in places, it has parallel paths. When you stop in Kearney, be sure to visit the Great Platte River Road Archway, which pays tribute to traders, trappers and adventurers like Miller who made their way to annual rendezvous.

Heading toward Scotts Bluff, you could drive along Interstate 80. I recommend taking U.S. 30, which runs parallel but north of the river. To my mind, this slower route is better because you will drive through the towns along the route: Lexington, Gothenburg, North Platte, Ogallala and more, rather than zipping past on a 75-mile-per-hour highway.

West of Ogallala, take U.S. 26 into Nebraska’s Panhandle. This route is parallel to—in some places overlays—the Oregon Trail and provides access to trail sites such as Ash Hollow, Courthouse Rock and Chimney Rock, arguably the most famous landmark on the Platte, and one that Miller was the first to portray when he sketched it in 1837.

Of more import to Miller though may have been the geologic formation farther west: Scotts Bluff, named for fur trapper Hiram Scott, an employee of the fur trading firm of Smith, Jackson & Sublette, who, with a partner, was responsible for transporting supplies to the Green River Rendezvous in 1828. Scott’s health was deteriorating even before he and his companions turned east, en route to St. Louis. He could no longer ride a horse by the time they were in present-day eastern Wyoming, and he was near death when the party reached the major rock outcrop. Here, they abandoned Scott, who soon died. The following year his remains were located and buried by William Sublette, and the geologic feature was subsequently known as Scott’s Bluff.

The rock outcrop is now a National Historic Site, offering a hiking trail linking the visitors’ center at its base with the top of the outcrop (you can also drive to the top of the bluff and hike along its rim to overlook the area). At the visitors’ center, be certain to view the original paintings by William Henry Jackson, a contemporary of Miller’s.

A White Horse

From Scottsbluff (yes, the city is spelled differently than the geologic feature), you’ll want to head to Fort Laramie in Wyoming.

At the time Miller was in the area, Fort Laramie did not exist, but the artist stopped at Fort William, operated by the American Fur Company, which he sketched. Later he used that drawing to paint a view of what he imagined Fort Laramie (the post that replaced Fort William) to be. Fort Laramie also started as a fur trade post, but the U.S. Army purchased it in 1849. A visit to Fort Laramie will help you get a sense of the important historical periods that affected this area: Indians, Mountain Men, overland emigrants and the frontier military.

While near the confluence of the Laramie River, where it joined the North Platte, Miller sketched An Early Dinner Party near Larrimer’s Fork. (Although the post was not yet named to memorialize Jacque Laramee, who had been killed in the area in 1821, some geological landmarks had been named for the French-Canadian fur trapper.) Miller’s pencil drawing had brown and yellow washes to give it texture, and the general scene was later colorized in a watercolor on paper titled Breakfast at Sunrise.

One of Miller’s best-known works is The Trapper’s Bride, which inspired Walt Whitman to include it in “Song of Myself,” his poem published in 1855. The original painting is owned and displayed by the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana (and as a side trip, I can enthusiastically endorse a visit to that institution).

The common element in the paintings Miller eventually created following his travels with Stewart is a white horse; Stewart had ridden one during their expedition together. This trademark horse is placed in almost every piece of art Miller developed as a result of the 1837 journey to the mountain rendezvous.

The horse has its head down in An Indian Giving Information for a Party Who Passed in Advance, by Impressions Left of the Ground but stands at attention in a pen and ink Herd of Wild Horses, which is now held by the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. The horse is in the background of Trappers Bride (part of a series of paintings), but is prominent in The Thirsty Trapper, which is in the collection of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

Clearly the immense vistas, wide open spaces and the grandeur of the West affected Miller. The landscapes he painted following his journey with Stewart show that vastness with big, colorful skies, layers of mountains and people or animals that are small, almost insignificant, as though they are barely specks in the landscape.

The Mountain Man—trapper—images Miller created are outstanding, and often seen. They have been used to illustrate books and magazines, and in exhibitions about the fur trade. Some are stunning portraits; others, almost cartoon-like (a pack mule kicking supplies hither and fro as it follows a trade caravan, or a man racing from a charging bear). Here, too, he uses the white horse as an element in his paintings, such as In the Rocky Mountains, where the horse drinks while standing in a lake of water as men cook a meal over their campfire. The original is at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska. Also at the Joslyn is A Trapper in His Solitary Camp, where the rangy horse used by the trapper dominates the center of the image.

That he so successfully captured the images of the Mountain Men—including their gear, clothing, weapons and horses—is due to the fact that Miller saw these trappers and traders firsthand. He did not need to research what their appearance would have been because he took part in the 1837 rendezvous itself. That makes works like his Pierre so striking, especially as the trapper and his donkey are predominant, while the camp for other traders or Indian participants at the rendezvous is a subtle component of the background.

Attending the Rendezvous

Speaking of the fur trade rendezvous that Stewart and Miller participated in, that’s the final leg of our journey.

From Fort Laramie, you’ll want to drive U.S. 26 to Interstate 25 and take that highway northwest to Casper. From there, head west on Wyoming Highway 220, stopping at Independence Rock and Devil’s Gate, if you’d like. Then turn north at Muddy Gap onto U.S. 287, following it through the Sweetwater Valley, before you turn southwest onto Wyoming Highway 28 and cross South Pass. At Farson, Wyoming, turn north on U.S. 191 through Pinedale and to Daniel, the rendezvous site.

A visit to the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale provides information and artifacts related to these rendezvous. The best time to come to this region is in mid-July, for the re-enactment of the Green River Rendezvous.

The era of the Mountain Men is re-created across the Rocky Mountain West every summer. In addition to the Green River Rendezvous, you can attend similar gatherings of modern-day blackpowder enthusiasts, Mountain Men and Indians at the Fort Laramie Rendezvous (Father’s Day Weekend, Fort Laramie, WY); Pelton Creek Rendezvous (late June, Laramie, WY); 1838 Rendezvous (Fourth of July Weekend, Riverton, WY); Sierra Madre Muzzleloaders Rendezvous (late July, Grand Encampment Museum, Encampment, WY); the Rocky Mountain National Rendezvous (early August; this event is in a different location every year and is not open to the public the entire time); and Fort Bridger Rendezvous (Labor Day Weekend, Fort Bridger, WY).

Viewing Miller’s Work

Any journey regarding Alfred Jacob Miller really must include visits to some of the institutions that hold his original work, for only when you are looking at the canvas or paper he actually touched will you truly appreciate his talent and the story of the West he presents.

Miller’s work is held by institutions across the West, and a select group of 30 pieces that comprise the Bank of America collection will be on the road over the next year in Kansas City, Houston and Philadelphia. Those pieces are representative of the broad spectrum that is Miller’s portfolio. He worked in a combination of media: ink and watercolor washes, gouache, pencil and oil. His art details mountain trapper subjects, as seen in Departure of the Caravan at Sunrise and Watching the Caravan and Indians of the West, in pieces like Indian Lodge on the Upper Missouri; Snake Woman Reposing; and On the Warpath—Running Fight. Fully capturing the experiences he had with William Drummond Stewart, Miller painted or sketched landscapes and wildlife like those featured in Stampede of Wild Horses and Elk Taking the Water.

Because Miller was a master at recycling, you will often see very similar images in different institutions. Each will be an original with subtle differences that those of you with a discerning eye will notice. Or, you could make it a bit of a treasure hunt across the West, trying to spot the differences in his broad portfolio as you follow Miller’s only journey across the American West, 200 years after the master artist’s birth.