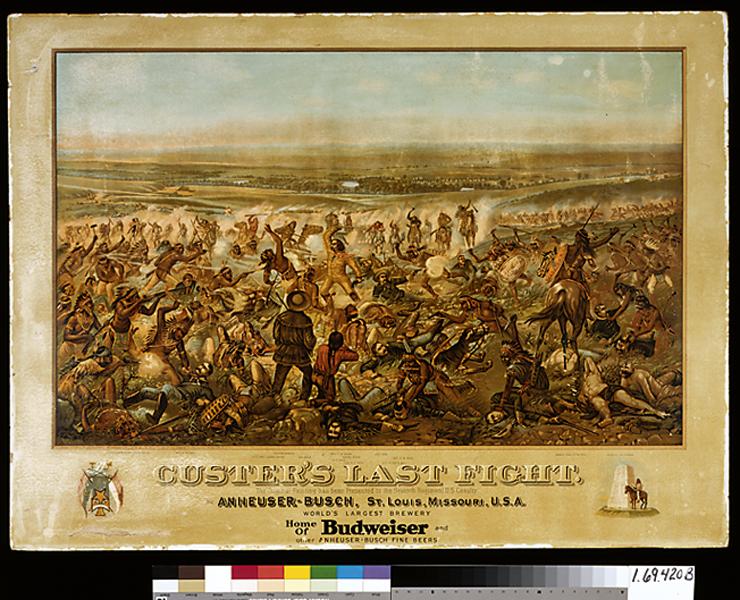

Montana artist Edgar S. Paxson’s painting Custer’s Last Stand is a gripping depiction of the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Yet unknown to most viewers, another battle lurks behind this oil on canvas: a battle between the Montana Historical Society in Helena and the Whitney Gallery of Western Art in Cody, Wyoming, for possession of the painting.

A war of words played out between the two museums and the artist’s heirs in the newspapers for four months starting in November 1962. The aggrieved party: Michael S. Kennedy, director of the Montana Historical Society. Not satisfied that the society was paying “proper respect” to their grandfather’s art, William E. Paxson and Bette Paxson Dartnell, who had loaned the painting to the historical society, announced they were going to sell it to the Whitney Gallery.

Kennedy told The Billings Gazette on November 10 that he was “shocked” the grandchildren had not consulted him or Gov. Tim Babcock on their decision, and that he had to read about it in the newspaper. He also disagreed with their assessment of the painting’s value at $50,000 (citing it to be closer to $10,000 to $15,000), and he pointed out its historical inaccuracies. (For example, some of the rifles in the hands of the cavalry were not yet in existence and most of the facial features of the cavalry were identical.)

William retorted the next day that only “apathy and false rationalization have been manifest and expressed through the years in Montana relative to the painting.”

Kennedy continued to storm the field, claiming the society had legal rights to keep the painting until March 1, 1963, after which, the Montana State Legislature could vote on whether to buy the painting.

A fruitless fight? Most definitely, as William made perfectly clear on November 19 that he had no intent to sell the painting to the society. He was disgusted that “Kennedy continually downgraded Edgar S. Paxson and his historical masterpieces,” and asked, “Is this proper for a state employee who is supposed to pridefully support and favorably publicize Montana’s cherished treasures? If he thinks and acts otherwise, he should resign immediately for the good of the state.”

Yet Kennedy refused to quit the fight. He countered on November 20 by announcing he was accepting, on behalf of the historical society, a patron’s donation of more than 100 works by Paxson, proving that he admired Paxson as an artist. “This puts the lie to the unfortunate rash of news stories inspired by the strange whim of William E. Paxson,” he said. “I think it is unfortunate that William E. Paxson has never seen fit to contact any responsible member of the state government in regard to this controversy, which started when he began firing acrimonious press releases all over the state. I feel the people of Montana will be able to judge who is loyal to the memory of Edgar S. Paxson.”

On November 22, Attorney General Forrest H. Anderson ruled on the side of the heirs, saying, “The indefinite loan agreement is basically a receipt, a promise to ensure the painting for $40,000 for the time it is in the Historical Society’s custody and promise to return them upon presentation of receipt as contemplated in the agreement.”

Kennedy still pressed on, yet by then, the locals were getting their own shots in. A Montana attorney wrote in a letter to the Wyoming State Tribune editor in December of 1962: “It is entirely fitting that Custer’s Last Stand, by Edgar S. Paxson, should hang in Wyoming. Certainly a state whose historical fame rests on the twin acts of infamy embodied in the Teapot Dome Scandal and the murderous Banditti of the Plains, those hired killers imported by the art-loving cattlemen of Wyoming to slaughter the helpless homesteaders, should own this grisly painting depicting man’s inhumanity to man.”

On behalf of the Whitney Gallery, Dr. Harold McCracken announced on December 11 that he could wait to buy the painting until the Paxson heirs and the historical society settled their dispute.

Despite William’s pronouncement that he refused to sell the painting to Montana at any price, a bill to purchase the painting was introduced in the Montana Legislature on January 5, 1963. On January 21, Speaker of the House Frank W. Hazelbaker said, “Custer’s Last Stand should be shipped to the Whitney Gallery. If Wyoming’s repository for such items is less fireproof than ours I suggest we ship soonest.”

William angrily sent a letter to Hazelbaker, stating, “Montana could no more buy Custer’s Last Stand than it could buy the Mona Lisa.”

Another reader weighed in on the battle on January 28, sending a letter to the editor of The Billings Gazette, asking, “Is Kennedy a despot or something? Have we given him the right to say what should or should not be kept among our art treasures in Montana’s Historical State Museum?”

Apparently so. On February 3, The Billings Gazette announced that Wyoming had won the battle. Custer’s Last Stand would be going to the Whitney Gallery, and Montanans could take a last look at the painting before it left the state.

That same day McCracken criticized Kennedy for downgrading the Paxson painting, stating that he was behind the times in current pricing of Western art. But McCracken also said he never agreed to pay $50,000 for Custer’s Last Stand: “I never pay for paintings until I get them.” (He did end up paying that fee.)

When McCracken received the painting on February 21, he called it the “most important historical painting of the West in existence today.” He also could not resist a parting shot at the director of the Montana Historical Society: “It is extremely unfortunate that such an important historical painting by such an important painter has been so sadly downgraded recently from a source ethically dedicated to the edification and perpetuation of our Western Heritage.”

Although this war of words was indeed bitter at times, no lasting grudge exists between the Montana Historical Society and the Whitney Gallery of Western Art. In fact, the museums have collaborated on several projects to further the study of the American West.

Custer’s Last Stand still hangs in the Whitney Gallery of Western Art. In 1988, William E. Paxson issued one of his last press releases, which ran in the Helena Independent Record. The article, titled “Painter’s Grandson Laments Loss,” reported: “William E. Paxson complained for years about the removal of the painting from Montana to the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Wyoming.” It also quoted William as saying, “although the Custer Massacre has inspired many paintings, only one is acknowledged by qualified experts to be historically accurate. And that is the Montana artist Edgar S. Paxson who painted the internationally famous painting.”

The battle that took place in 1962 was not mentioned.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming; Gift of the Coe Foundation, 1.69.420B –

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming; Museum Purchase, 19.69 –