– Courtesy Nell Shipman Productions –

Westerns have always had a sizable female following. But while we’ve long had female on-screen icons like Maureen O’Hara and Barbara Stanwyck, less than a half-dozen have sat in the director’s chair.

In the “silent” days of 1913, Canadian Nell Shipman began writing and starring in Westerns. By 1920, she was co-directing her own features in which, rather than playing the typical waif in need of rescue, the outdoorswoman was more likely to rescue the male lead.

Shipman retired in 1924, and it would be 35 years before another woman would take on the mantle. Sixteen-year-old British beauty Ida Lupino was already a star when, in 1934, she came to Hollywood. Continuing to act, in 1949 she began to write and direct tough films noir. Ten years later she directed her first Western, an episode of Hotel de Paree. Series star Earl Holliman, recalls, “She was a movie star, and I had watched her for years. Directors who’ve acted can be very helpful. She was sharp, knew exactly what she wanted, where she wanted the cameras.” Still, on her first Western, communication wasn’t always easy. “She was English, and she talked about when the heavies go up to the bar, ‘to have a couple of hookers,’ which in England means a tall whiskey. And the assistant director asks the producers, ‘Where will we get these hookers?’ Ida was talking about drinks; they were talking about whores.” Lupino would go on to direct episodes of Have Gun-Will Travel, The Rifleman, The Virginian and others.

Nine years later, Lina Wertmuller, the first woman ever nominated for a Best Director Oscar, became the first, and probably only woman to direct a Spaghetti Western. The Belle Starr Story was shooting in Yugoslavia when star Elsa Martinelli insisted the director be replaced, with Wertmuller. “I thought it was a great move,” recalls male lead Robert Woods. “I love her films; she’s a true artist.” Wertmuller worked for hours on scenes with Martinelli, and wrote her a poignant speech about Woods’ character being the only man she ever loved. “Then halfway through the picture, they had the Indian girl kill me! But I still got my sixty grand.”

– Ida Lupino with Camera Courtesy True West Archives –

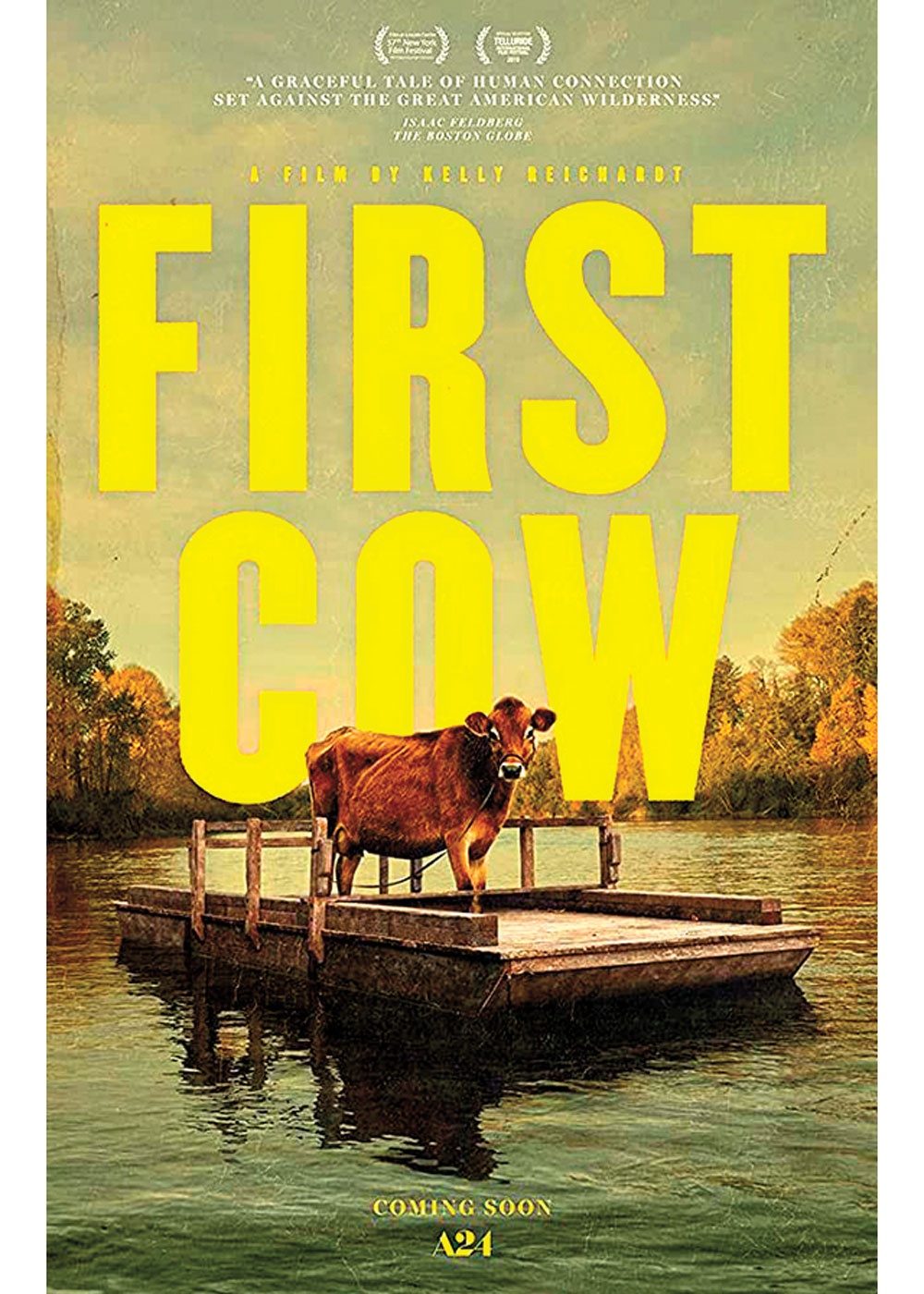

Now in the 21st century, Kelly Reichardt has directed two fine, critically acclaimed Westerns. Meek’s Cutoff (2010) is the story of a tiny wagon train whose Oregon Trail journey is waylaid when wagon master Meek takes them on a “shortcut.” Her new film, The First Cow, is the seriocomic story of the first cow introduced into an Oregon frontier and the entrepreneurs who build a business on filched milk. The director did not set out to make Westerns. “The only Western image that really impressed me as a kid growing up in Miami was the Marlboro Man.” In Meek’s Cutoff, “[there’s a] a bossy man on a horse, a wandering Indian, wagons, oxen and cooking over an open fire. So, the Western was hanging over me while making that film. The visual language of the genre is strong. With First Cow I didn’t feel I was walking in the footprint of the genre. I could do whatever I wanted, maybe because many of my influences came from Asian films and French painters.”

– “First Cow” Poster Courtesy Film Science –

What challenges does she face making period pictures? “Harsh landscapes, extreme weather, rattlesnakes, oxen and a volatile actor. Meek’s pushed people to their limits and brought out the best and worst in us all. The rewards, to name a few: times of a perfect synchronicity with crew, actors and nature; the lovely animals; shared research.” That shared research, which included the lead actors, produced films of startling accuracy. About Meek’s, she said, “The art department research brought [Production Designer] David Doernberg and me in contact with a lot of strange and interesting people. Michelle Williams was reading the diaries from the pioneer women, and Zoe Kazan had been researching the frontier since she was a little girl obsessed with Little House on the Prairie.”

First Cow is not as grim as Meek’s, but Reichardt doesn’t call it a comedy. “I really don’t put it in any certain category. I think it has weight and humor and a searching quality. But it was fun cutting the film and it often made me laugh.”

Considering the striking but nontraditional beauty of the films, it’s no surprise that Reichardt and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt have many influences. “Winslow Homer for certain, and Robert Adams’ photography, pioneer wildlife photographer William L. Finely, the paintings of Michael Brophy, who also took me on scouts out in the high desert of Oregon. The Westerns of Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher.”

Would more women assuming the Top Hand role make a significant change in Westerns? “The genre already is what it is. That language is already in stone. Now that more women are getting the chance to direct, they can comment on the genre, but creating a whole new language for it is probably impossible.”