Galen Clark was, for want of a better term, a loser. Yet all of his trials and tribulations ended up giving this country a great natural treasure: Yosemite National Park, which celebrates its 125th anniversary this month.

In 1853, Clark had long ago left his native Canada, moving through Missouri and other American locales. He was 39 and widowed, had farmed out his five kids to relatives and gone through multiple bad businesses. He was broke and suffering from consumption—tuberculosis—and doctors had given him six months to live.

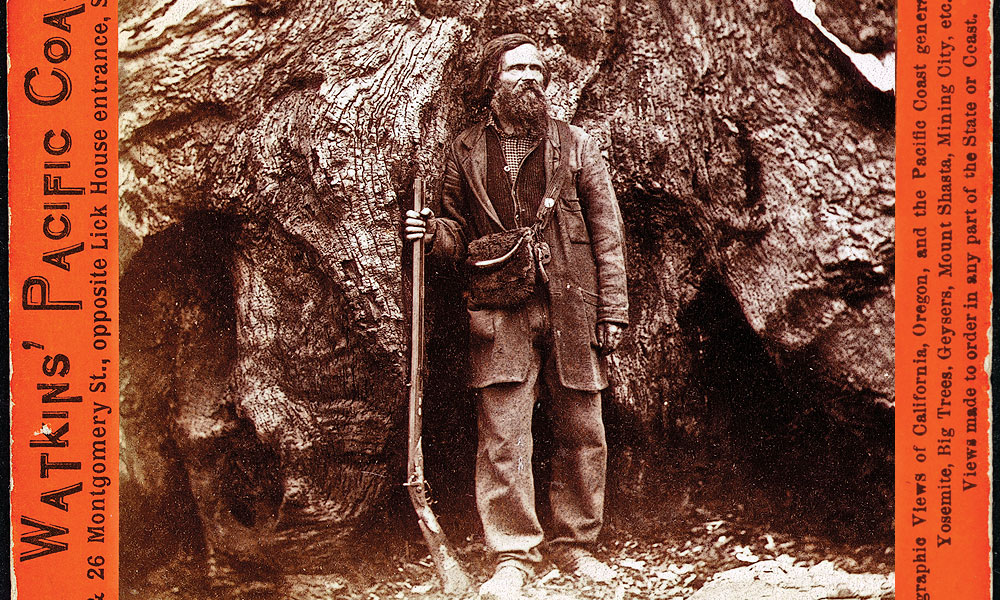

He moved to the mountains of California, in what became Mariposa County. As his health improved, he explored the area, learning its secrets, seeing what only the Indians had before him. One discovery was the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoia trees, an imposing landmark then as it is now.

Three years past his death date, Clark wrote about the area. He pushed lawmakers to protect it from development and proclaim its treasures to one and all. His efforts picked up steam, and, in 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation that granted the grove and the Yosemite Valley as California’s first state park.

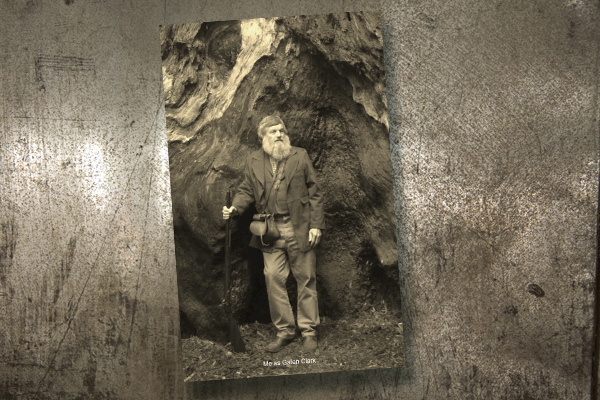

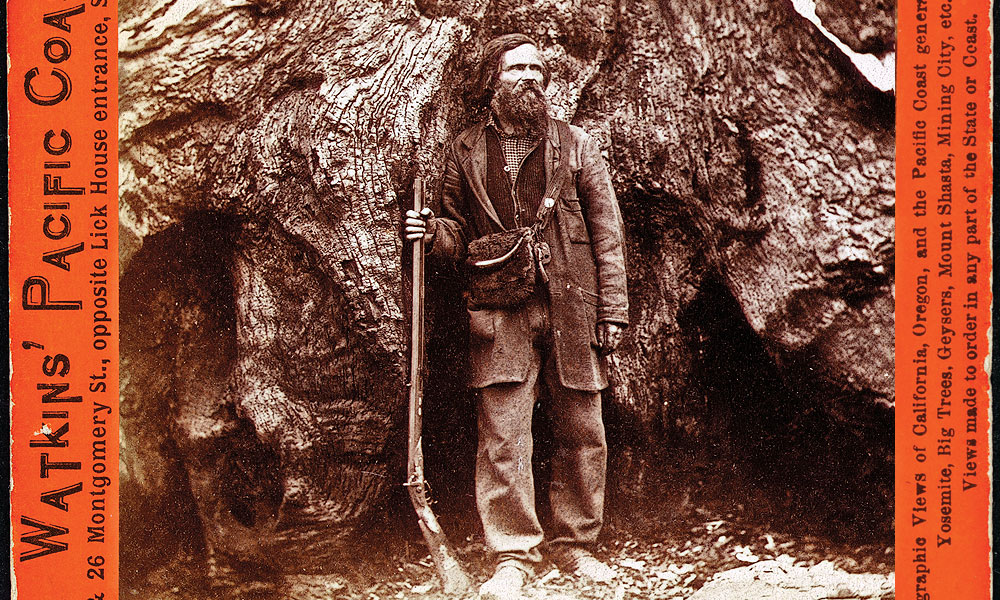

Clark benefited from that decision. In 1866, park overseers named him the official guardian of Yosemite—in effect, he became the nation’s first park ranger. In that role, which he held for 22 years, he protected the area (quite a job for just one man). He prevented any illegal cutting of timber or construction of buildings, kept the peace with Indians and settlers, and provided guided tours.

By the late 1880s, naturalist John Muir was convinced that only the federal government could truly protect the area. With Clark’s help, Muir’s campaign led to President Benjamin Harrison signing into law, on October 1, 1890, Yosemite as the third national park—it included not just the valley and the sequoia grove, but also the surrounding mountains and forests.

The park allowed Clark to run a hotel and charge a fee as a guide. But he had not become a better businessman; Clark was constantly in debt. In the last decade of his life, he wrote three books on the park—Indians of the Yosemite Valley and Vicinity, The Big Trees of California and The Yosemite Valley—to pay his bills. While the books are informative, Clark left out one important character: himself.

In his final years, Clark lived at the Summerland spiritualist colony near Santa Barbara, where his house still stands. He also paid visits to his daughter in Oakland, where he died, nearly 96, on March 24, 1910.

What a legacy he left the nation—more than 1,100 square miles of mountains, spectacular cliffs, waterfalls and giant trees, and an incredible array of flora and fauna. Clark may have been a business failure, but Yosemite National Park is an incredible measure of success.