– all photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

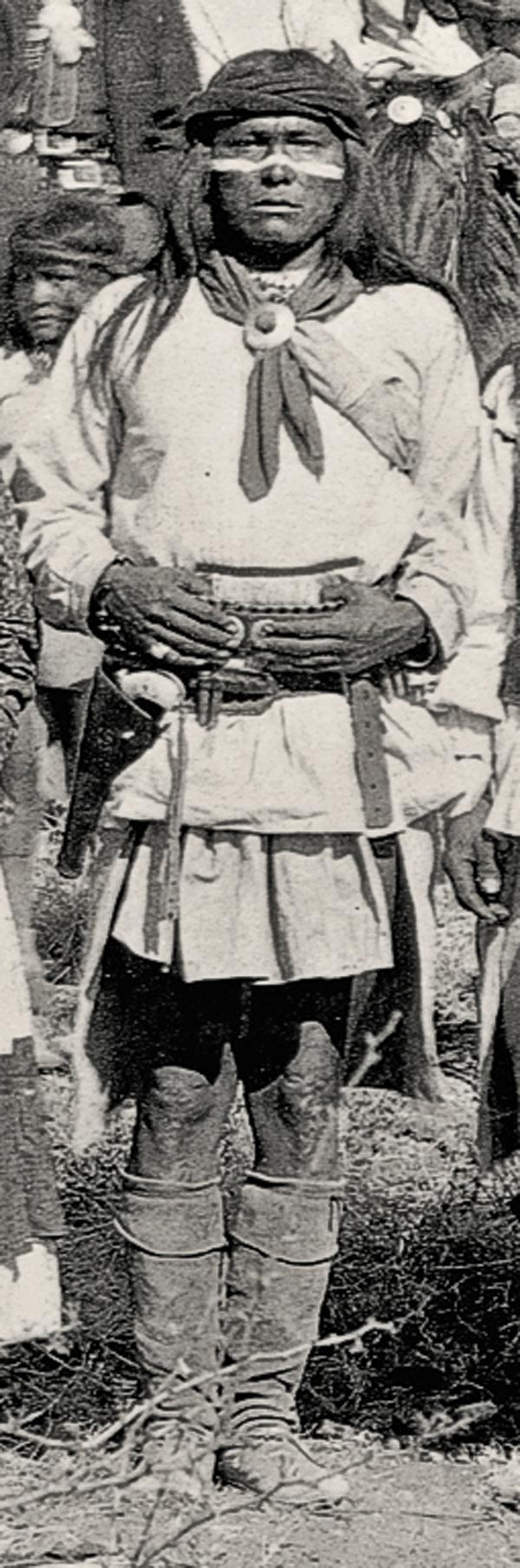

Adelnietze’s proud bearing is so obvious in C.S. Fly’s photos—the white paint carefully drawn over his nose and face, as he steadfastly gazed into the “strange box” that captured his image in a desperate time.

The calmness he depicted, however, was not in his heart.

He no doubt had thoughts similar to those echoed down through the ages: “Surrender? No longer will the sky and earth be sewn together as it is here in the land of my grandfathers. I must pray to Ussen, our Creator. My family waits to learn what the white men who write tracks across paper have to say.”

Adelnietze was among the Apaches at Cañon de los Embudos in northeastern Sonora, Mexico, in the spring of 1886 and probably fought in most of the major raids and skirmishes up to that time. He had served as a U.S. Army scout and was an important member of Naiche’s band, possibly Naiche’s cousin.

He did not comply with the terms of the surrender agreement made with Gen. Nelson Miles at Skeleton Canyon. In September 1886, Adelnietze and six others at Skeleton Canyon, including Natculbaye and Satsinistu, disappeared into the Sierra Madre Mountains, where they joined other Nednhi and Chiricahua guerrilla survivors of the Apache Wars.

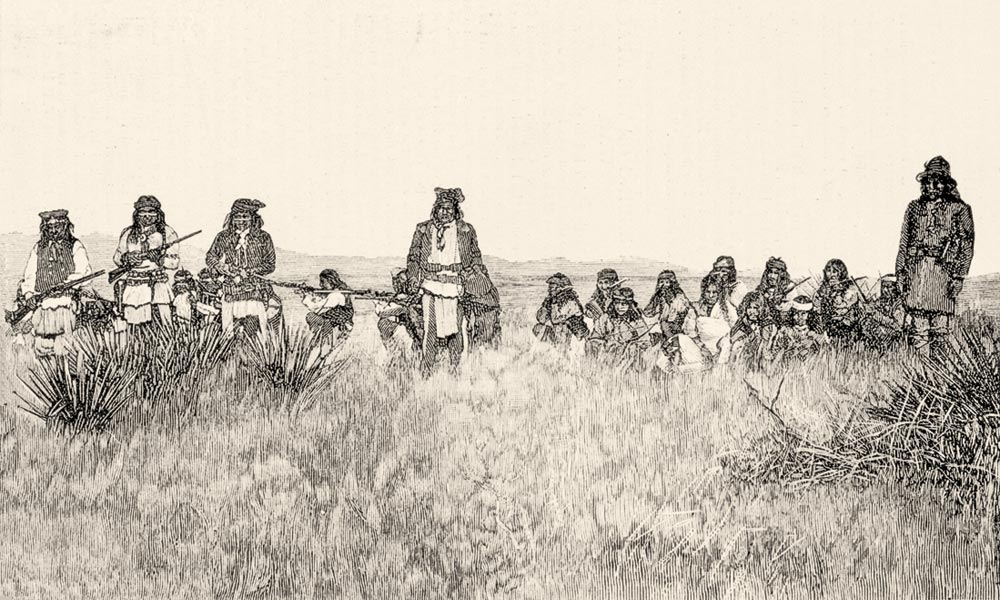

From 1886-1896, his small band might have had an opportunity to live peacefully within the vast rugged canyons of the Sierra Madre. Their families were with them, and they continued to ransack the small Mexican and U.S. ranchos and pueblos for extra supplies. However, times had changed along the borderlands. More troops patrolled, and settlers streamed into the native lands. Raiding was easy, but escape was no longer guaranteed.

Adelnietze did not know about the horrors being heaped upon his brethren in the hellhole prisoner of war camps in Florida, Alabama and later Oklahoma Territory. No doubt he missed his kin, but at least he was free to smoke a cigarillo, take a cow when needed or trade with Mexicans. Perhaps he had turkey quills filled with gold dust to purchase supplies from willing traders. This fragile existence was much better than anything Naiche and Geronimo endured. But then the Apache murders of Horatio Merrill and his 16-year-old daughter in December 1895 and of Alfred Hand in March 1896 became the last straw.

Eventually, the military and civilians relentlessly pursued Adelnietze and his small band to Guadalupe Canyon, a rocky passageway often used by the Apaches as an easy escape route into Mexico from Arizona Territory. A decade had passed since the surrender, but these fateful and brutal turn of events led the U.S. to Adelnietze’s ranchería in May 1896.

A military ambush was planned and brutally executed. A few days earlier, toddler Apache May (shown on p. 96) had survived an attack that destroyed all the renegade Apaches’ cached supplies. She was found wearing a dress stolen from the Merrill’s home and was later adopted by famed rancher John Slaughter. The Apache military scouts also found Adelnietze’s rifle—an 1873 Springfield with a shortened barrel—field glasses, bows, arrows and moccasins.

Fleeing for their lives, the band scattered, as was Apache custom. Several scouts, troopers and civilians closed in for a second time. Most escaped, but Adelnietze was mortally wounded.

Tracking him, the scouts first found discarded blood-soaked leggings and then, eventually, his body. One of the bloody leggings was given to the editor of The Tombstone Prospector as a souvenir.

The life blood of the proud, freedom-loving Adelnietze soaked into the ridges along Guadalupe Canyon, 10 years after he was photographed at Embudos canyon.

Lynda A. Sánchez researches Apache history, legend and lore, following the footsteps of her mentor, Eve Ball, and is working on her next book, The Broken Loop: A History of the Lost Apaches.