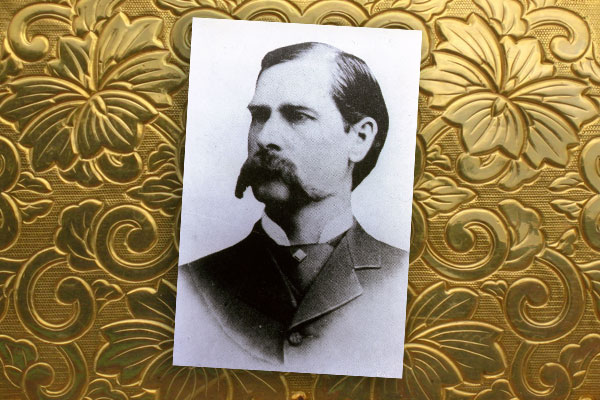

The writers came to Wyatt Earp. They wanted his story; they wanted to know all about that street fight in Tombstone, Arizona, and the Vendetta Ride where the lawman became a force unto himself.

For the most part, Wyatt shut up.

He would rather talk about mining or gambling or the other activities of his life. A taciturn man by nature, he avoided the shoot-’em-up stories. Christenne Welsh, who remembered walking to the ice cream shop holding hands with Wyatt and her grandfather, never heard him talk about his gunfights. Many others who knew Wyatt came away with the same experience.

So the writers were left to craft the stories of Wyatt’s more wilder encounters in the frontier West—some with his help; some with the help of opposing old-timers; some with the help of their own fantastic imaginations.

We think we know Wyatt. But often what we know about him comes more from the writers than from Wyatt or any other legitimate source. Today, a new generation of writers has set out to try and tell fact from fiction, putting aside the old stories from the past.

This is not easy, by any means. No less an eminence than Bill O’Reilly, a political commentator on Fox News Channel, and his writer David Fisher repeated one of the biggest lies in their book Bill O’Reilly’s Legends & Lies: The Real West, released in April.

O’Reilly repeats the canard that John Henry “Doc” Holliday taunted Ike Clanton on the night before lawmen Holliday and the Earp brothers fought the Clanton brothers and other cowboys during Tombstone’s famous Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881; Holliday told Ike that he had killed his father. Newman H. “Old Man” Clanton actually died on August 13, 1881, at Arizona’s Guadalupe Canyon during a massacre when Mexican troops came slightly across the U.S.-Mexico border to descend on a group of herders. Many years later, writer Glenn Boyer (1924-2013) repeated the claim that the Earp brothers and Holliday had committed the murder, then invented the part about Holliday taunting Clanton to set up the gunfight. O’Reilly and Fisher feasted on the fiction.

Boyer was not the only writer to invent portions of Wyatt’s life. Stuart Lake (1889-1964), Wyatt’s authorized biographer, Frank Waters (1902-1995) and a host of other writers told fantastical stories about the lawman that made their way into the legend. For instance, Lake claimed Wyatt studied law in his youth, which is not true. Some stories we simply cannot resolve.

Perhaps the most vexing is the tale of Ellsworth, Kansas, where Wyatt stepped into the middle of a tense situation to arrest the dangerous Ben Thompson. Lake wrote a glorious account that cannot be substantiated by any other source. Yet he also provided just enough hints that the claim cannot be refuted.

Researcher Tom Gaumer intensively studied the event and located a newspaper story dated after the 1931 publication of Lake’s Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal in which the editor asked townsmen if anyone could recall Wyatt’s involvement. None could. Gaumer also located a newspaper article reporting that Wyatt’s brother, James, had been in Ellsworth at the time. Wyatt and James often traveled together. So we are left with a quagmire—a highly suspicious story that we can neither fully refute nor support.

Lake wrote a hagiography, a book glorifying Earp and exaggerating his deeds. Nearly three decades later, Waters would do just the opposite, presenting a book full of false tales that demonized Earp.

From its publication in 1960, Waters’s The Earp Brothers of Tombstone would be the heart of the anti-Earp belief system that came to dominate the field. Waters presented Wyatt as a criminal, involved behind the scenes in stage robberies and other outlawry. But his most horrifying portrayal is of Wyatt as a cad, who publicly stepped out on his wife with another woman. Waters said he based his stories on interviews with the widow of Wyatt’s brother Virgil, Allie. But when Allie read the manuscript, she insisted the book not be published. Waters placed the unpublished manuscript at the Arizona Pioneers’ Historical Society for two decades until he reclaimed it and wrote his updated version.

This image of Wyatt as a criminal stood for years. While I was researching my book, Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend, both Jack Burrows and Pat Jahns told me that they had read the original manuscript, which was nothing like Waters’s book. Not until 1998, when researchers Jeff Wheat and S.J. Reidhead located the original manuscript at the University of New Mexico, did Earp historians realize what extraordinary liberties Waters had taken with the story.

In the original manuscript, nobody mentions Wyatt cavorting around town with another woman. In fact, Allie did not seem to know Wyatt had any involvement in Tombstone with Josephine Sarah “Sadie” Marcus, the woman who later became his common-law wife. Waters fully invented those remarkable scenes of Wyatt prancing around town with the strumpet Sadie, while his ever-loving common-law wife, Mattie, sat home polishing his boots.

After Boyer located Wyatt’s family during the mid-1960s, he added to the collection of wild yarns. Among his dubious gifts to the Earp field were inventing a newspaper conspiracy masterminded by Tombstone Nugget Publisher Harry Woods against Holliday and the claim that Cochise County Deputy Sheriff Billy Breakenridge and outlaw leader “Curly Bill” Brocius were gay.

On the rare occasions when he did talk, Wyatt also played a hand in the false stories. As he aged into his senior years, he told several writers that, on his way out of Arizona, he had killed outlaw John Ringo. That, of course, was not possible because Ringo was killed on July 13, 1882, three months after Wyatt had left Arizona; Wyatt would have had to return from Colorado to kill Ringo, then leave without being seen. Wyatt apparently realized the problem and did not make the claim that he had killed Ringo when he talked to Lake.

For the most part, the writers were the ones who exaggerated and denigrated Wyatt’s legend, mostly with their own imaginations. The intense research done on Wyatt and Tombstone during the last two decades has revealed a life even more interesting than the legends. He acted bravely, even heroically at times. Sometimes he made extremely poor choices that led to shame. The real Wyatt that has emerged from the legends is more human—and far more intriguing—than the falsehoods foisted upon us by generations of writers.

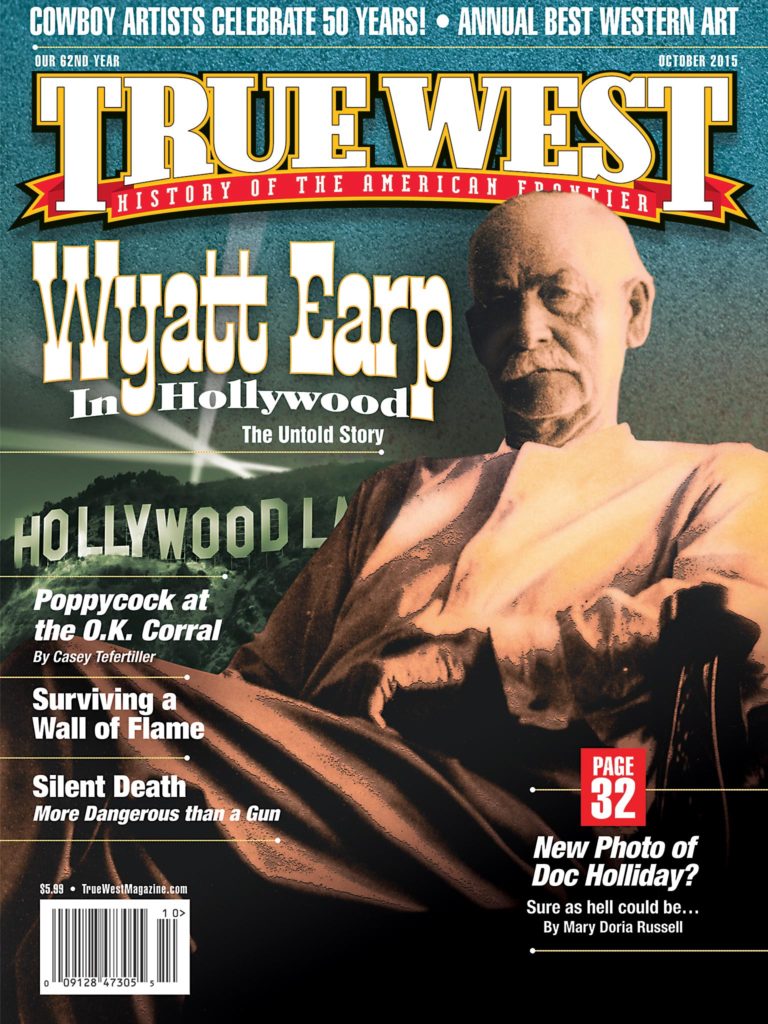

Click Here for a behind the scenes look at our October 2015 issue.

Casey Tefertiller wrote Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend. His Wyatt Earp’s Last Deputy will be released next year by Turner Publishing; the book will deal with how writers have constructed false legends of Wyatt’s life.