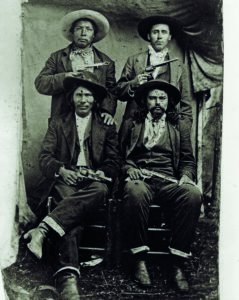

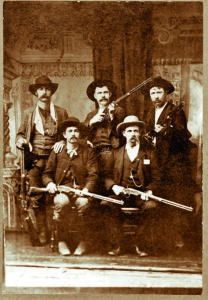

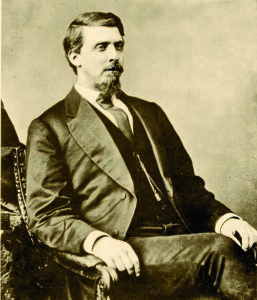

– All Photos Courtesy Art T. Burton Unless Otherwise Noted –

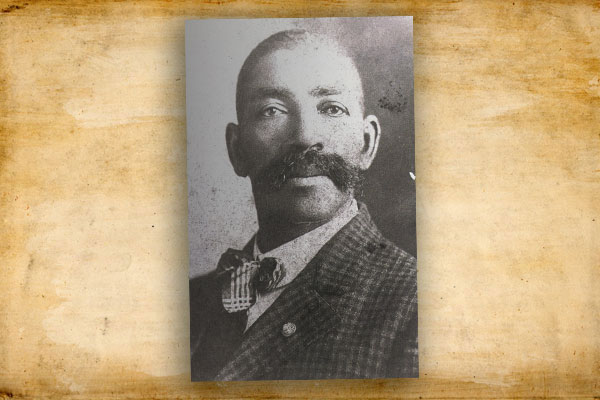

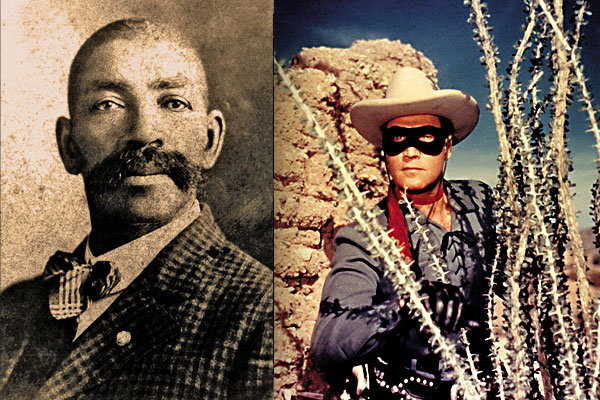

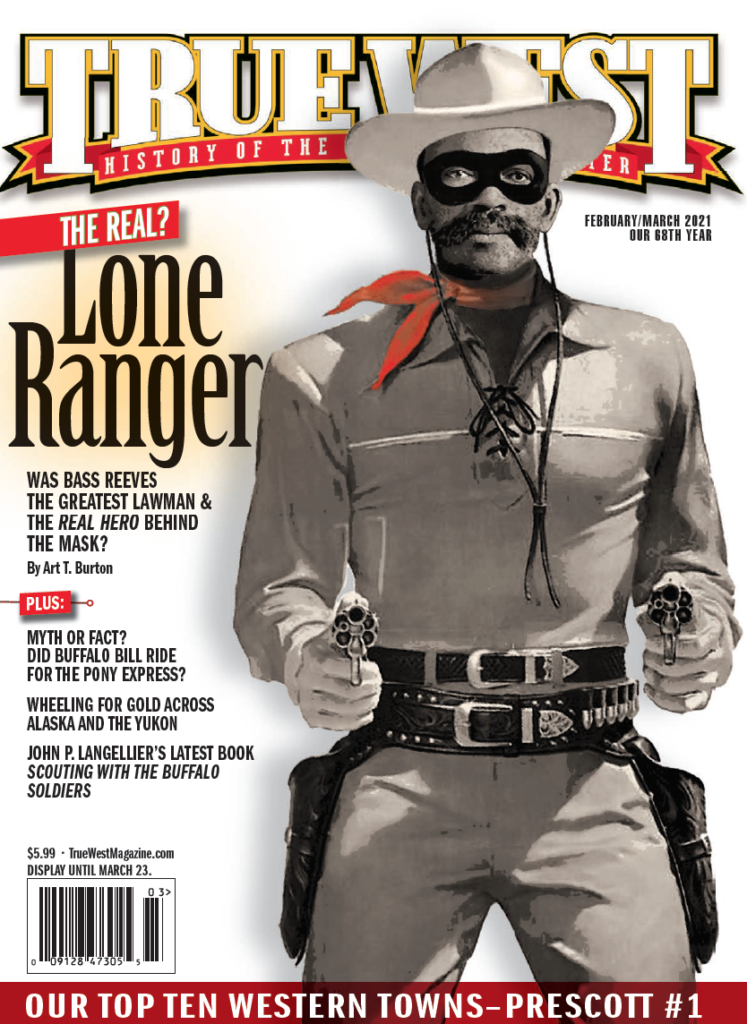

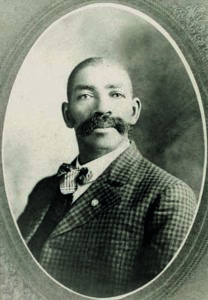

Born into slavery, the Arkansas native became a lauded, and legendary U.S. deputy marshal.

Bass Reeves began his life as a slave in the state of Arkansas in July 1838, near the town of Van Buren. He and his family were owned by William Steele Reeves, who was originally from Hickman County, Tennessee. While working as a water boy and field hand with his family as a youngster, Bass would originate and sing songs about guns, rifles, knives, robberies and killings. This troubled his mother greatly as she thought he wanted to be an outlaw. When Bass was eight, the Reeves family moved to northern Texas to Peter’s Colony in Grayson County near Sherman, Texas.

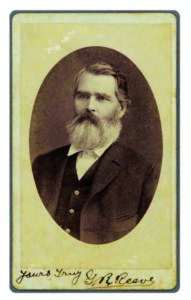

Sometime after moving to Texas, Bass became a valet/body servant to William S. Reeves’ son, George R. Reeves. Bass also served as bodyguard, coachman and butler. The owner allowed Bass to use guns to hunt and learned that he was a crack shot. Bass won many turkey shoots for his master, which in Texas was prestigious for George. In 1848, George was elected tax collector, and in 1850, he was elected sheriff of Grayson County. In 1855, George was elected to the Texas House of Representatives from Grayson County. At the outbreak of the Civil War, George was made an officer in the 11th Texas Cavalry Regiment, second in command to Col. William G. Young. Bass went with George into the war, serving as his body servant. Early in the war, the 11th Texas Cavalry Regiment fought at the Battle of Chustenahlah in the Indian Territory and the Battle of Pea Ridge, also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern. After the war, George was reelected to the Texas State Legislature, and at his death on September 5, 1882, he was Speaker of the House of Representatives for the State of Texas. Reeves County in West Texas is named for him.

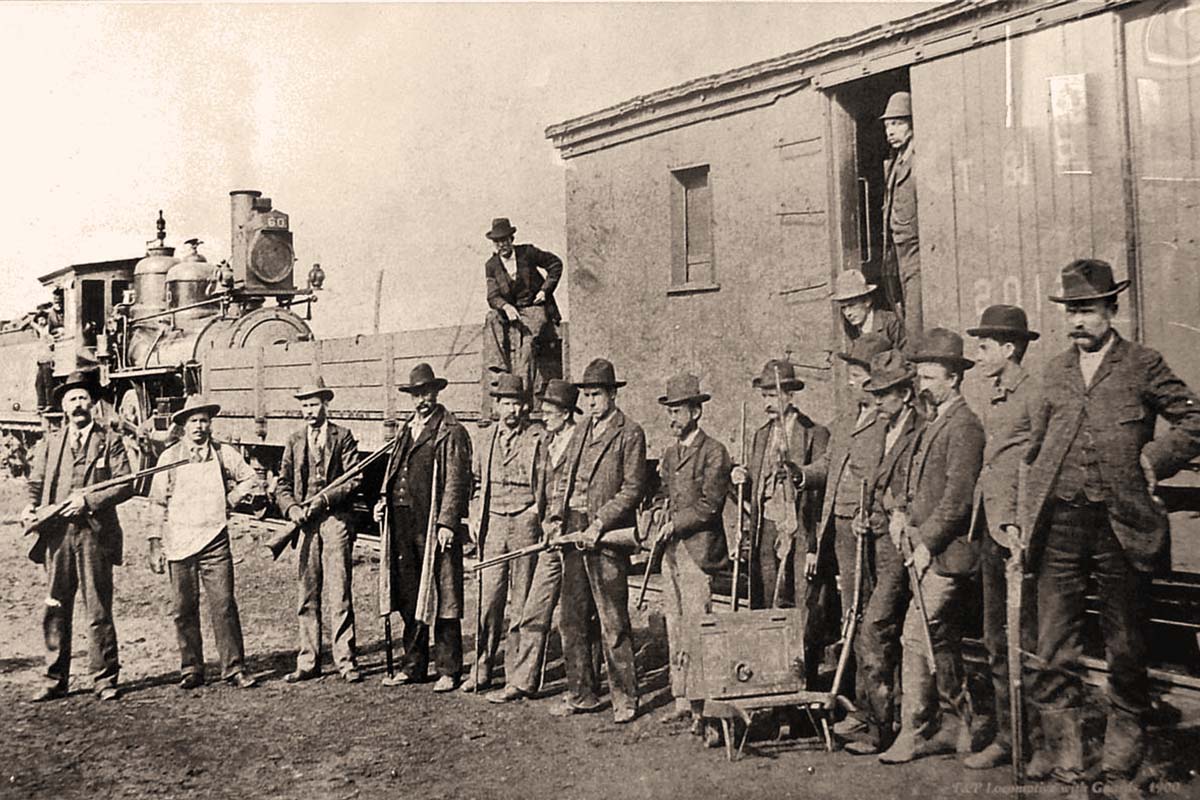

– Courtesy DeGolyer Library, SMU –

Family history states that Bass and George got into an argument over a card game during the Civil War. Bass got so upset at being cheated, he beat his master down and knocked him out. For a slave to hit his master in Texas was punishable by death. Bass set out for the Indian Territory and was taken in by Seminole and Creek Indians. Here, he learned Indian languages, the lay of the land and complete mastery of pistols and rifles. Bass was also taught tactics of disguise in riding horses and stealth in combat.

After the war, Bass Reeves settled down outside Van Buren, Arkansas, and maintained a horse ranch and small farm. At this time Bass was married to his wife, Jennie, who was also from Texas, and they had four children. They would later have 11 children in the household. Bass raised horses and served as a scout for deputy U.S. marshals going into the Indian Territory. In this capacity, his familiarity with the land served him well. The federal jail court was in Van Buren for the western district of Arkansas and Indian Territory. In 1871, the federal court and jail were moved to nearby Fort Smith.

After some malfeasance and misappropriations of federal funds, William Story was fired as the judge of the Western District of Arkansas federal court at Fort Smith. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed a U.S. congressman from Missouri named Isaac C. Parker to take over the Fort Smith federal court in March 1875.

U.S. Marshal James Fagan was replaced not long after Judge Parker took over the court with a Union veteran, Daniel P. Upham. Earlier, Upham had commanded the Arkansas State Militia and had destroyed the Ku Klux Klan in that state. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, most guards, turnkeys, cooks and bailiffs for the Fort Smith federal court were African Americans.

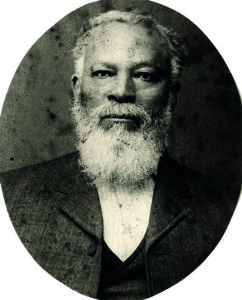

Bass Reeves was commissioned in late 1875 as a deputy U.S. marshal for the Fort Smith federal court. He was not the first Black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi River. As early as 1867 there was a posse out of Van Buren, Arkansas, sent to investigate a stagecoach robbery at Atoka, Choctaw Nation, that was led by a deputy U.S. marshal named “Negro” Smith. Bynum Colbert, a Choctaw Freedmen, was a veteran of an Arkansas United States Colored Regiment of the Civil War and served seven years with the 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment post-Civil War. Colbert began his tenure as a deputy U.S. marshal with the Fort Smith federal court in 1872, three years before Bass Reeves’ commission.

In the late 1870s, although Reeves was a deputy U.S. marshal, much of his work was as a posseman for other deputy U.S. marshals, including Robert J. Topping, James H. Mershon and Jacob T. Ayers. In December 1878, Reeves served as a guard at Fort Smith for the executions of a Black man named James Diggs and an Indian named James Postoak, both for murder. In May 1881, Reeves made his first trip to Detroit, Michigan, to the House of Corrections, along with five other deputies transporting 21 prisoners by train via St. Louis.

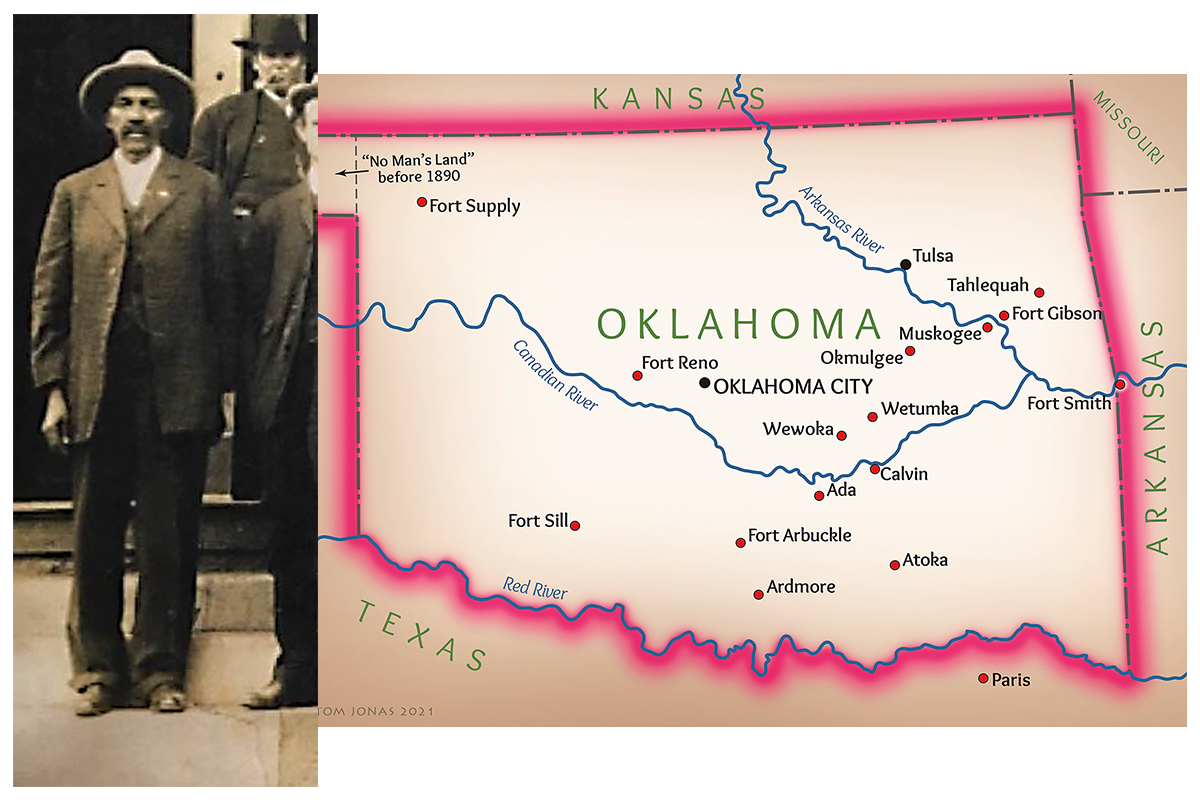

Reeves became known in the early 1880s for bringing prisoners back to the Fort Smith court in double digits. Deputies would work out of Fort Smith and venture into the Indian Territory with warrants and open warrants. They would travel with a crew, at least one posseman or more, a cook, a guard and one or two wagons with supplies. Bass would travel west to Fort Sill, north to Fort Reno and sometimes Fort Supply, picking up and arresting felons who broke federal law in the Indian Territory. The round trip would be approximately 400 miles and would take one or two months, depending on high water in the rivers and creeks.

Reeves was an expert with pistol and rifle and could shoot ambidextrously. He was 6’2” tall and extraordinarily strong. The residents of the territory said he could whip any two men with his fist. Research shows that he could shoot accurately with his Winchester rifle up to 500 yards or a quarter of mile, and he had several gunfights during which he shot felons at that distance.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

The following is just a short sampling of Reeves’ police work in the 1880s. The Fort Smith Elevator reported Reeves coming to town in August 1882 with 16 prisoners. The same news-paper reported Reeves in August 1883 bringing in 13 prisoners. The St. Louis Globe Democrat in February 1884 reported Reeves bringing in 12 prisoners to Fort Smith. The Fort Smith Elevator reported Reeves bringing in 12 prisoners in April 1884. The Arkansas Gazette in September 1884 re-ported Reeves brought 15 prisoners to Fort Smith. The same newspaper in March of 1885 reported Reeves bringing in 13 prisoners. The St. Louis Globe Democrat in October 1885 reported that Reeves had arrested 17 felons in the Indian Territory and brought them to Fort Smith.

Reeves’ greatest gunfight was in 1884. He tried to apprehend the fugitive Jim Webb, who had been foreman on the Billy Washington Ranch in the Chickasaw Nation. Webb had earlier killed a Black farmer who accidently burned some grazing land on the Washington Ranch. Reeves and Webb had a gunfight in June 1884 near Bywater’s Store, which was a stagecoach stop. Reeves shot Webb with his Winchester at 500 yards after Webb narrowly missed him several times.

Tragically, Reeves accidentally shot his cook on one of his trips into the Indian Territory in 1884. He was brought up on first-degree murder charges in January 1886 and relieved of duty. Reeves was arrested and lodged in the Fort Smith federal jail until he could make bond in June of that year. At his trial in October 1887, Reeves was found innocent. He went back to work as one of the deputies of the Western District of Arkansas at Fort Smith under Judge Isaac C. Parker. Ironically, Reeves was brought up on first-degree murder charges, not manslaughter or criminal negligence, after a new U.S. marshal was hired, the first former Confederate officer Reeves would work for.

Research shows that Reeves stayed in Fort Smith until 1893. During that era, he made one of his top arrests with the capture of the Seminole Indian fugitive known as Greenleaf in April 1890. Greenleaf had been on the run for 18 years and had murdered three white men and four Indians and had never been arrested. After his capture by Reeves, residents came from as far as 20 miles to see that Greenleaf was in handcuffs before they took him to Fort Smith. Later in November 1890, Bass and his posse raided the home of the legendary Cherokee Ned Christie, who was wanted for murdering a deputy U.S. marshal. It was later proven that Ned was not guilty of the crime. When Reeves located the cabin of Christie in the Cherokee Nation, his posse burned it down, but Ned escaped capture and death. Later, he was killed by a large federal posse in 1892, never to prove his innocence. Bass Reeves said the largest haul he made while working for the Fort Smith court was bringing in 19 horse thieves from the Fort Sill area.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

In 1893, Bass Reeves was transferred to the Eastern District federal court at Paris, Texas. This court at that time had jurisdiction over most of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. Reeves was headquartered at Calvin in the Choctaw Nation and carried many of his prisoners to the federal commissioner at Pauls Valley in the Chickasaw Nation. Reeves remained with this federal district until 1897, when he was transferred to the new Northern District of Indian Territory at Muskogee. At Muskogee, Reeves worked under Leo E. Bennett, the former Indian agent for the Five Civilized Tribes, headquartered at the same town. The Northern District was made up of the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole Nations. The Creek Nation had a heavy African Indian population, as did the Seminole Nation. Muskogee was the principal town in the Indian Territory and had a large African American population with many federal offices in town. Muskogee was unique with two Black business districts that were thoroughly integrated and catered to the diverse population in the frontier town.

After 1900, Muskogee had city police, with two deputy U.S. marshals stationed there, Bass Reeves and a white man David Adams. Adams served as Reeves’ posseman, and they were involved in numerous police actions together in and around Muskogee. In May 1902, Reeves and Adams went to the town of Braggs, Cherokee Nation, to quell racial strife. They arrested, without incident 15 white men and eight Black men and brought them to the federal jail in Muskogee. Later, Reeves was made the principal lawman for the large African American community in Muskogee, and he had several Black assistants in that role. After 1905, Reeves did not arrest as many white felons as he had earlier in his career, due to the large influx of white settlers into the territory and racial attitudes shifting.

On November 17, 1907, Indian Territory became the new state of Oklahoma. The U.S. Marshals office in Muskogee was downsized, and Reeves found himself out of work. Reeves was now 69 years old, the only deputy U.S. marshal I have found that started with Judge Parker’s regime in 1875 and worked up to Oklahoma statehood in 1907. Reeves’ unemployment did not last long because, at the start of the new year in 1908, he was hired as a Muskogee city policeman and given a beat downtown. He liked to brag that there was never any crime reported on his beat.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

Reeves died in Muskogee on January 12, 1910, after a short illness. He is believed to be buried in a small cemetery on Fern Mountain Road west of town. Reeves was interviewed in 1902, and at that time he stated that he had arrested over 3,000 men and women who broke federal law in the Indian Territory. At his death, several newspapers, in and out of state, stated he had killed more than 20 men in the line of duty. Bass Reeves was indeed the Invincible Marshal.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

Art T. Burton, a retired college history professor, has written four critically acclaimed history books on the American Western frontier. He is a member of Western Writers of America and the Chicago Westerners Corral, and was made an honorary territorial marshal by Oklahoma Governor David Walters.