How long it had lain in the West Texas desert, no one knew.

It was 1972, and the firearm looked as if it had been undisturbed for at least a century. Nonetheless, there it was, a dark brown hulk, yet glistening with the patina of desert varnish in the West Texas sun. As the two young mounted cowboys riding fence, Mark Bleakely and Barry Heath, spotted the gun, they quickly sunk spurs and dashed toward it. Clearing their saddles in a heartbeat, each claimed the prize—a Colt Third Model Dragoon pistol.

A rusted iron gun, yet due to the arid climate of the Big Bend country, this frontier relic remained in surprisingly good condition. The revolver had turned dark on its right side, while the left, which had laid down in the dry sandy soil, retained a relatively shiny surface. The wood grips had long since disappeared, but the roll-engraved cylinder scene of Texas Rangers charging Comanche Indians was still visible, although much of the exposed right side was largely obliterated—save for a barely discernable serial number.

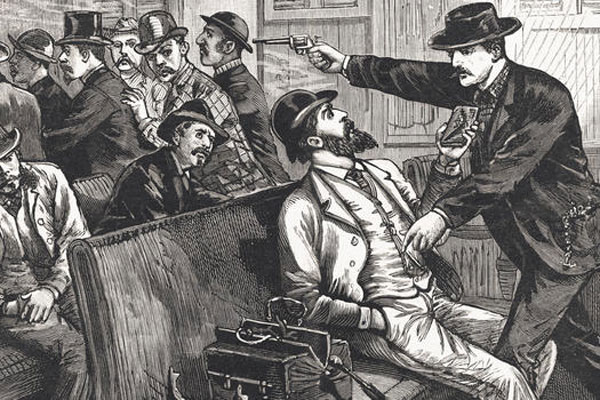

Adding further to the mystique of the old cap-and-ball Colt, the hammer was jammed in half-cock position. All six of the revolver’s chambers were loaded, and five of the cylinder’s nipples were capped, while the sixth one was not. An exploded percussion cap was found lodged between the hammer and the frame’s hammer channel, making it impossible to further cock the piece until the cap remnants were removed—a common problem with open-top percussion revolvers of the mid-19th century.

What was this Colt’s story? The Dragoon is martially marked with the “U.S.” stamping on the frame. The “13303” serial numbers on the frame, trigger guard and back strap, and the “13342” number on the cylinder indicate production at around 1853. The “U.S.” stamp and the fact that the cylinder’s serial is only 39 numbers apart give evidence of military use and of being reassembled with parts from other arms—either in the field during the heat of combat or in the garrison during “gang” cleaning—with no thought given to possible collector value more than a century in the future. Curiously though, the round ball loading is more indicative of a civilian-type charge, since the military generally employed combustible paper cartridges using conical bullets.

This Colt may have been dropped in desperation, very likely during a running fight. Was it lost by a lone dragoon trooper fleeing for safety when the Colt jammed, then was dropped? Was he wounded, did he make it, or was he part of a command, outnumbered and unable to take the initiative, that caused these horse soldiers to make a hurried retreat, leaving their temporarily inoperable, but still valuable, revolver behind? Or is it possible, still, that this Dragoon Colt wound up in the hands of an Indian warrior, a border bandit, a scalp hunter or any of a number of early Texas travelers who may have suffered a similar fate? One thing is certain … this Big Bend Dragoon Colt suggests a life and death struggle. Only the West Texas country knows the real story, and the desert holds on to its secrets.