If the Colorado River is the “American Nile,” as some fanciful writers have called it, was there a Cleopatra along its banks?

More than one woman could claim this title because no less than a half dozen early heroines left their marks on the history of this meandering body of water. Each of them braved many hardships, as did the American Indian women who came before them.

Little is known about the mothers, wives, daughters and sisters who, for generations, made their homes along the banks of this life-sustaining waterway prior to recorded times. The coming of the Spanish changed this situation. Indeed, one of the first women to follow her soldier husband to the lower Colorado left the earliest written account of life there, albeit her recollections recounted a sad saga.

Señora de Islas

Following in the footsteps of the intrepid Jesuit missionary Padre Eusebio Kino and the hard-riding comandante of the Presidio of Tubac Juan Bautista de Anza, two Franciscan padres, Francisco Garces and Tomas Eixarch, came to convert the Quechan. More commonly known in early chronicle as the Yumas, these natives had long carved out a culture where the Colorado River met the Gila (today’s border with Mexico, Arizona and California). These people did not embrace the Christian message with open arms. Their resistance eventually prompted the highest ranking military officer in New Spain, Teodoro de Croix, to order the establishment of a pair of settlements among 3,000 native peoples.

So it was that Alfrez don Santiago de Islas, an Italian-born soldier of fortune who came up through the ranks of the Dragoons of Mexico, was dispatched to the area. Beginning the journey at Tubac, Arizona, the ensign shepherded nearly 200 colonists, including his wife Maria Ana, westward over the Sonoran Trail to carve out two new outposts in the wilderness.

The Quechans disapproved of the presence of these intruders. On July 17, 1781, their smoldering resentment ignited. That morning, as Fray Garces offered Mass, blood chilling war cries erupted. The killing soon commenced. Corporal Pascual Baylon fell as the first casualty. The rebellion against the Spanish interlopers was in full swing. Terror reigned.

Señora de Islas took swift action. She gathered the women and led them to the church in hopes of finding sanctuary from the slaughter. The attack raged throughout the day. From the refuge of the chapel Maria Ana witnessed the most tragic sight of her life. In a letter written four years later she recorded, “That night the Yumas began to burn our houses and belongings and kill as many of our people as they could. That was the night my heart was broken, when my beloved husband was clubbed to death before my very eyes.”

Besides her husband Alfrez de Islas, an estimated 103 settlers and soldiers also perished. Maria Ana and 73 other women and children escaped the fate of the men who were cut down during the outbreak.

After this incident, Spain’s plans to lay claim to the Colorado withered. Missions La Concepcion and San Pedro y Pablo—where Fort Yuma now stands—crumbled back into the earth from which they were fashioned. After the red and yellow Spanish gave way to the Mexican tricolor, no efforts were made by La Republica Mejicana to tame this no man’s land.

This state of affairs continued until the war between the U.S. and Mexico brought a renewed interest to the river. First, the Colorado was an obstacle to be crossed by Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West as they trekked toward the Pacific to conquer California in the 1840s.

The Great Western

After the discovery of gold in California, which became part of the U.S. due to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, communities began to spring up along the lower Colorado River. This included Fort Yuma and its nearby civilian neighbor Arizona City—the seed that grew into today’s Yuma. Arizona City’s first structure was allegedly a restaurant that came into being because of a force of nature remembered in history as the “Great Western.”

Supposedly standing over six feet tall, this veritable Victorian Amazon also was known to her clientele as Mrs. Sarah Bowman. She had a string of other names because she had been married on several occasions. Her most recent spouse, Albert Bowman, was a German-born man who listed his occupation as an upholsterer in the 1860 census. In the same census, Sarah hailed from Tennessee and was 47 years old; she listed her property as being worth $2,000, no mean sum in those days.

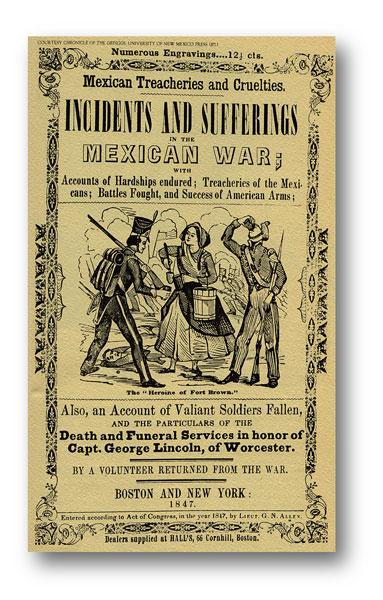

This statuesque redhead first became part of frontier lore in 1845 when she attached herself to Zachary Taylor’s Army as a laundress, cook and Jill of many trades as the Americans encamped along the precarious Texas-Chihuahua border. She reportedly arrived driving a pair of ponies pulling her rig containing her pots, pans and supplies to set up a mess for Taylor’s officers. At the time she was referred to as Mrs. Sarah Bourdett. Possibly her husband at that point was an enlisted man. Regardless of her marital status, she arguably would become the most noted camp follower of the War with Mexico.

During that conflict she gained the nickname “Great Western,” conceivably because of a huge steamer that was, in the 1830s, the largest steam vessel afloat. Perhaps Sarah when aroused was not unlike her namesake when she was under steam. Indeed, Texas Ranger Rip Ford indicated she “had the reputation of being something of the roughest fighter on the Rio Grande; and was approached in a polite if not humble manner….”

Characteristic of her bravata, during an 1846 bombardment by Mexican artillery against Fort Texas (later re-designated Fort Brown), she served coffee and soup to the besieged American defenders without regard for the enemy fire. With “cannon balls, bullets, and shots…falling thick and fast around her” she remained cool and “…continued to administer to the wants of the wounded and dying…,” one soldier recalled.

On another occasion, when a member of Taylor’s Army, which by now was in Mexico, burst into Sarah’s establishment in Saltillo babbling the enemy had cut the nearby American forces to ribbons, she dropped him with a blow between the eyes. As he fell she exclaimed: “You son-of-a-bitch, there ain’t Mexicans enough in Mexico to whip Old Taylor.”

As the conflict neared an end she found her return north was not permitted unless she had official status. This minor legality did not dissuade her so she sought a husband among the 2nd U.S. Dragoons to gain passage home. As dragoon trooper Samuel Chamberlain, the author of My Confessions, recalled, Sarah simply went up and down the unit shouting: “Who wants a wife with $15,000 and the biggest leg in Mexico! Come my beauties, don’t all speak at once—who is the lucky man?” Evidently the strategy worked because Sarah headed homeward with the troops as Mrs. Davis.

She eventually wound up in El Paso, Texas, and from there trekked westward with some Forty-Niners. This brought her to Arizona’s Fort Yuma where, among other things, she set up an officers’ mess. Soon thereafter, a priest recorded she was the first white woman in Arizona City. Moreover, she may well have been the first woman to own property in what became the Grand Canyon State.

Regardless of this possibility she subsequently sold her adobe house and real estate, located near present-day Main and First Streets, to Hooper & Hinton who operated a sizeable mercantile business from the site. Before this sale, however, Sarah continued to demonstrate a softer side when, in 1856, she took care of Olive Oatman after that young woman’s return from Indian captivity.

A decade later the Great Western died on December 22, 1866. She was interred under the mysterious name Mrs. Bowman-Phillips and laid to rest with full military honors at Fort Yuma’s post cemetery. In 1890 all the graves were removed and the remains transported to the National Cemetery at the Presidio of San Francisco; her headstone, overlooking the Golden Gate, reads “Sarah A. Bowman.” Even so, she will long be remembered as the Great Western!

Frances Boyd

Another woman who uprooted because of an association with the U.S. Army was Frances Boyd. Accompanying her spouse, an officer with the 8th Cavalry, Frances traveled to a place she considered “as far away as China, particularly because there was then no transcontinental railroad.” She further decried, “I had lived in New York City all my life, and considered it the only habitable place on the globe.”

Thus it must have been a great shock to Frances when, in 1869, she and her newborn daughter set out from California so the family could be reunited at Arizona’s Camp Date Creek, the duty station taken up by 1st Lt. Orsemus Boyd. To reach this isolated outpost, Frances and her newborn traveled overland to a place where, in her words, “no woman could be induced to go.…” She attributed this contention to two factors: “First there is no church there. Second, and mainly, because many Indians were.”

Her arduous overland trek from California strengthened her negative attitude about what she saw as a Godforsaken country. The wearing ordeal, which, at times, was without water, took its toll. As a consequence, when she and her party crossed the Colorado basin near Fort Mojave and arrived at that stark garrison along the river’s muddy banks, even this site was a welcome one. She recalled: “We gladly crossed the river and shook the dust of California from our feet.”

Gathering her thoughts, she surveyed her surroundings, finding the fort to be a “mere collection of adobe buildings with no special pretensions of comfort….” Fatigue overshadowed the desolation because, although the heat was oppressive and “made it an uncomfortable sleeping place,” this ramshackle assemblage provided a “haven of rest.” After all, she admitted, the situation could be worse: “The muddy river sluggishly wound its way to the Gulf many miles below, and nine months of the year the temperature on its banks was torrid. Fort Yuma, at its mouth, was noted for being a veritable Tophet.”

Frances emphasized her point by relaying a yarn about a Fort Yuma soldier who ventured out “in the middle of a July day, and never returned. Diligent search served only to discover a huge grease-spot and pile of bones on the parade ground.”

Admitting her point was preposterous, she felt it illustrated the harshness of a place where “eggs, if not gathered as soon as laid, were soon to be roasted if the sun shone on them.” To avoid the souring mercury, “Those who had the leisure to do so spent the greater part of their time in the bath….” Even the local “Indians would remain in the stream for hours at a time, their heads covered with mud as a protection from the sun’s rays.” After enduring the inferno for two days, Frances and her daughter pressed on to Camp Date Creek and other assignments, never again to lay their eyes on the Colorado.

Martha Summerhayes

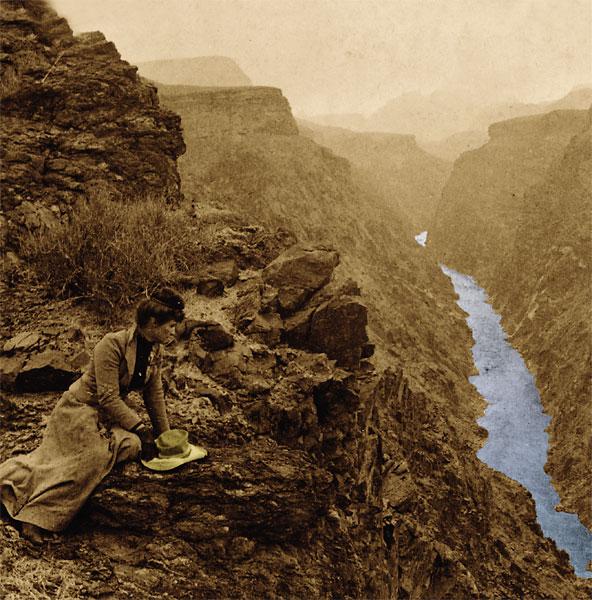

Unlike Frances Boyd, many other women who followed the guidon took up residency along the American Nile. One of these army wives, Martha Summerhayes, became well known for her memoirs titled Vanished Arizona. In this timeless tome she recounted her first journey up the Colorado River.

Martha emphatically complained she “had never felt such heat, and no one else had or has since.” She had no choice but to resign herself to the “dreadful heat” that did not abate once the steamer reached Fort Yuma. Martha noted this garrison was “said to be the very hottest place that ever existed.” To make her point she repeated the oft-told parable of the “poor soldier who died at Fort Yuma, and after awhile returned to beg for his blankets, having found the regions of Pluto so much cooler than the place he had left.”

Yet, for Martha, the “fort looked pleasant to us….” In fact, having spent “twenty-three days of heat and glare, and scorching winds, and stale food, Fort Yuma…seemed like Paradise.” This respite ended all too quickly. Soon she was steaming slowly upstream on the paddle wheeler Gila. Martha bemoaned her fate. “When we departed, I felt, somehow, as though we were saying good-bye to the world and civilization….”

With a sense of foreboding she began her “journey up the Colorado River, that river unknown to me except in my early geography lessons—that mighty and untamed river, which is to-day unknown except to the explorer, or the few people who have navigated its turbulent waters.” The interminable voyage passed slowly with everyone wandering about the deck, “first forward, then aft, to find a cool spot.” After 11 days, a quick trip according to the captain of the Gila, the boat tied up at Fort Mojave. A week and a half on the Great Colorado during midsummer prompted her to vow, “nothing would ever force me into such a situation again…my only feeling was…to get out of the Territory in some other way and at some cooler season.”

Yet months after she made a vow to avoid this place, her husband Lt. John Summerhayes received a transfer from a relatively pleasant assignment at Fort Apache to a posting at Ehrenberg. Martha accompanied her beloved Jack to this purgatory where she came to envy the local Mexican women who wore a “low-necked and short-sleeved white linen camisa” about the house. Her conservative Victorian husband forbade such a fashion. This meant she “sweltered during the day in high-necked and long-sleeved white dresses….”

Without doctors, milk and butter for much of the year, and because of the relative scarcity of many items that Easterners took for granted, the Ehrenberg stay seemed like solitary confinement for the couple and their new baby. Realizing the hardships he had caused his family, Jack arranged for their return to relatives in the East.

Ellen McGowan Biddle

Army wife Ellen McGowan Biddle experienced similar privations when she headed to Arizona. After a stay in San Francisco she, too, made her way down the California coast to transfer at the mouth of the Colorado to a smaller conveyance named Cocopah. She described the Colorado River as: “broad and shallow and full of quicksands that are constantly changing…it flows though deep canons…the walls of which in some places rise over six thousand feet; it also flows through the Great [Grand] Cañon, and then through broad, sluggish channels to the sea; the only navigation is along that part of the country where the rivers separate California from Arizona…the whole country being barren and barbarous.”

While the river’s features intrigued Ellen, she was shocked when she saw the Indian “men entirely naked except [for] a piece of cotton which they wore about their loins and hanging down front and back….” Imagine her surprise when she dined with the Summerhayes, whose Indian manservant was also glad in this attire, which Martha thought suited him perfectly and appealed to her “aesthetic sense.” Needless to say Ellen was even more disenchanted with the region than Martha, who, in some respects, came to terms with her surroundings.

Ellen Hayes Robinson

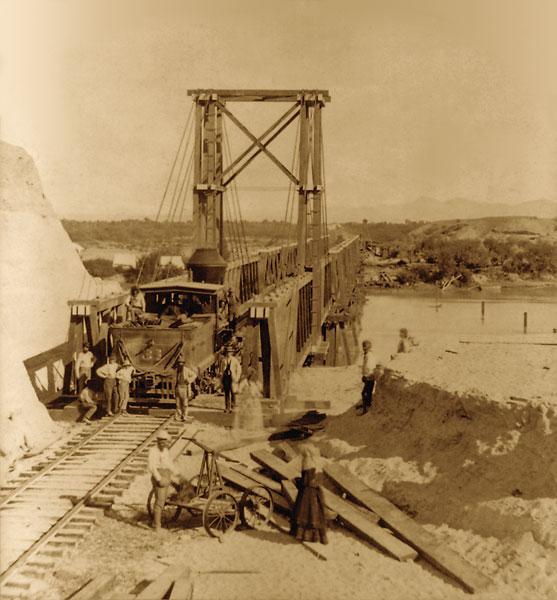

In the cases of military wives such as Martha Summerhayes and Ellen Biddle, their stays along the Colorado proved relatively brief. That was not so for women whose husbands made their living along the Rio Colorado as merchants or river men. Such was the lot of Ellen Hayes Robinson, who had never been more than 50 miles from home back East before accompanying her groom, a steamboat captain, to the end of the earth. Setting out in 1870, via the newly completed transcontinental railroad, she made the first part of her odyssey with comparative ease. The only inconvenience was the coal dust from the smokestack that covered her so thoroughly that on arriving in the Bay Area her “hair was like a broomcorn.”

After that, her life became even more difficult. From San Francisco the newlyweds made their way to the gateway to the Colorado, Port Isabel, where homesickness set in as her letters to family reflected. Another type of sickness, a physical one, befell Ellen’s husband, who was many years her senior.

Adding to her declining circumstances, the scorching weather forced Ellen to keep her trousseau packed away because even her lightest-weight outfit was too heavy. She eschewed fine feathers and bought a calico, one of the only practical solutions to the climate for a proper Easterner.

The fact that she had gained weight also precluded her from donning the wardrobe she had hauled with her on the honeymoon. In a letter dated Christmas Day 1870, she wrote she “…was weighed about first of October, weighed 113. Think now I would come nearer to 130. I have the most trouble with my clothes, making them large. Just finishing a new calico.”

Ellen’s groom made no remarks about her added pounds, but she thought it was wise to “lose and more than I have gained when the warm weather comes….” Ellen’s resolve may have been laudable, but not practical. Her added girth was a natural outcome of her change in condition. The rather naive mother-to-be ultimately realized the cause of her change in dress size. Months later, as the blessed event drew near, Ellen boarded the steamer Mohave bound for Fort Yuma where the nearest American physician could be found. On September 20, 1871, she delivered her baby, but with the help of a friend, rather than the aid of a doctor, because the boat was still inching its way upriver when the labor pains began.

In the meantime, the gallant medico left his residence and rowed all night to link up with the mother and her newborn. The next morning, he examined the two before giving them a clean bill of health and his blessing to return to Port Isabel. By the summer of 1872, Ellen and her infant daughter were released from their exile. They would leave the faraway frontier forever. Two years later, with her ailing husband’s death, she would take her daughter back to Maryland and home.

Cleopatras of the Colorado

Whether they left after a brief stay or remained for their entire life, pioneer women played an important and often unsung role in the history of the Colorado River. Despite isolation, often wretched conditions and scores of hardships, many a Cleopatra left her mark on the American Nile, and each one deserves to be remembered for her perseverance and indomitable spirit.

John Langellier received his PhD in history from Kansas State University. He is the author of dozens of publications focusing on military subjects, and he has also served as a consultant to motion pictures and television.

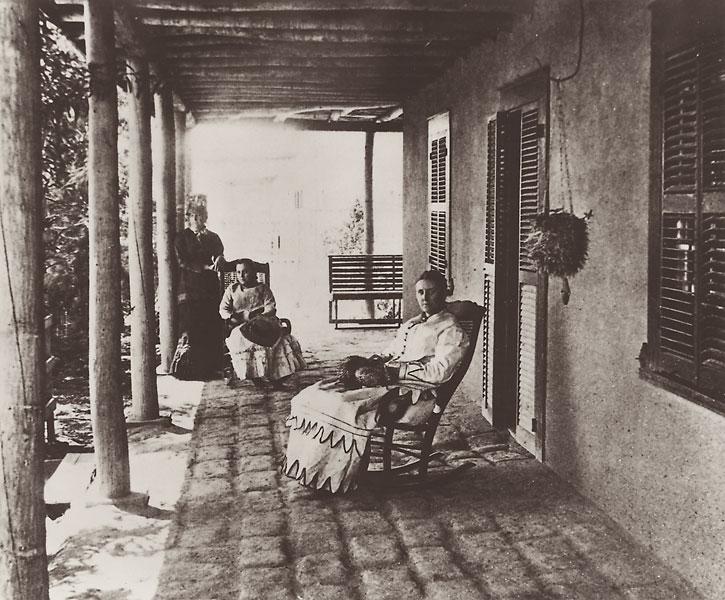

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy John Langellier unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –