— Courtesy of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas —

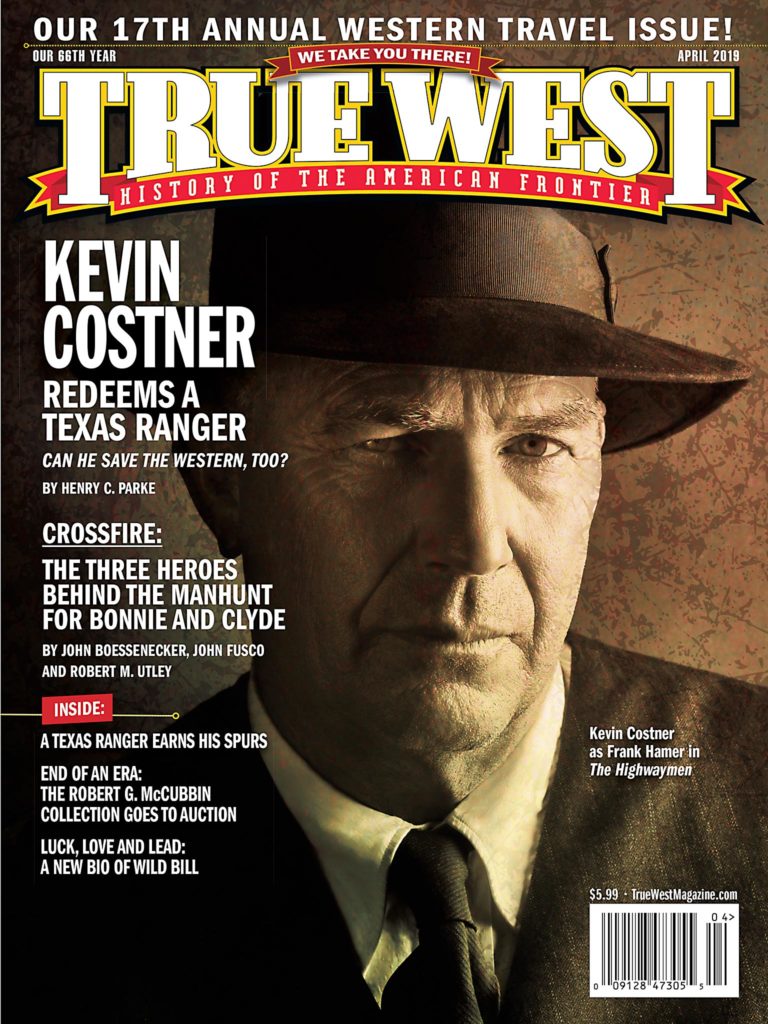

Three historians slice and dice what actually happened in one of the greatest manhunts in American history. We have decided to run all of the opposing evidence from Robert Utley, John Boessenecker and John Fusco, and let you, the reader, decide for yourself. We blew out the entire editorial well and went wall-to-wall with first class editorial warfare; these are heavyweights going at it, toe-to-toe. And, while they don’t always agree, you can sense the passion all three of them have for the subject at hand. If you read this issue and then watch the Fusco-written Netflix movie, The Highwaymen, you will not only have a solid idea of what really happened, but you will know where the bodies are buried, so to speak.

So what do you think?

–True West Editors

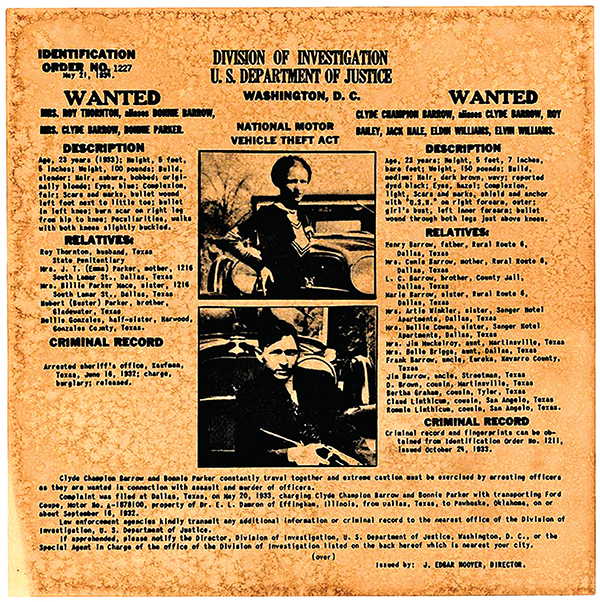

Frank Hamer vs. Bonnie and Clyde

John Boessenecker’s Version

When the Barrow Gang seemed uncatchable in 1934, Texas turned to its greatest Ranger to track them down and bring them back, dead or alive.

— Courtesy John Boessenecker —

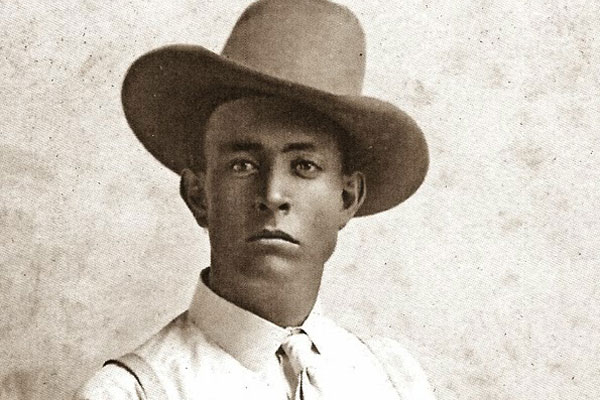

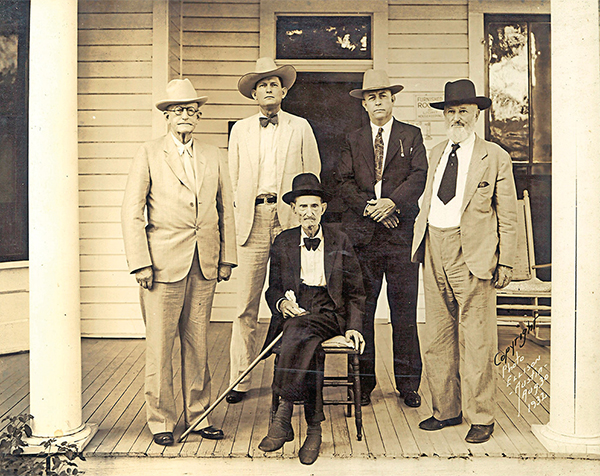

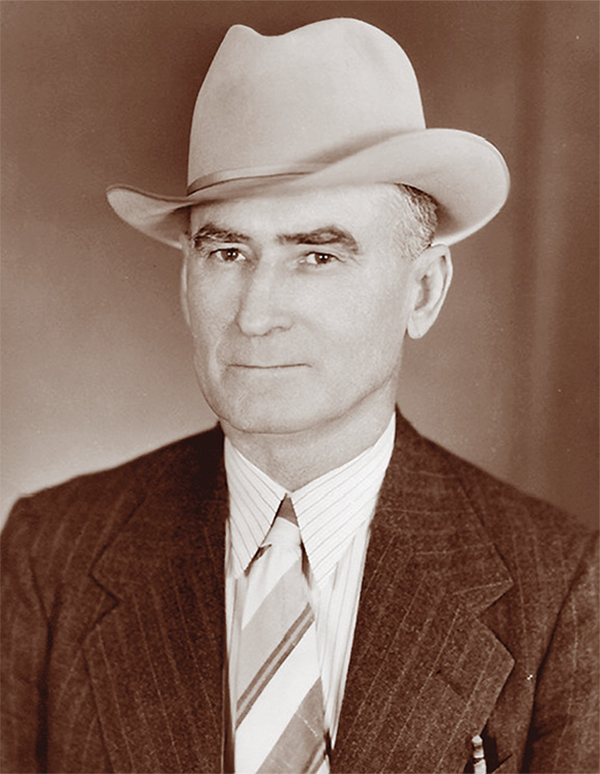

Frank Hamer’s career began during the closing years of the Texas frontier, and saw him transition from a horseback Ranger into a motorized gangbuster of the 1930s. In between, he served decades as a lawman, in and out of the Texas Rangers: city marshal of the rowdy east Texas town of Navasota, special officer in Houston, deputy sheriff of Kimble County, U.S. prohibition officer and Texas Ranger captain. Among his countless exploits, he played a prominent role in the so‑called Bandit War of 1915, when Mexican revolutionaries surged across the border and raided in south Texas. In 1917 he got mixed up in the Johnson‑Sims feud, killing one man in the feud’s climactic gunfight in Sweetwater. Hamer’s role in a violent vendetta was certainly the low point in his professional life. In 1921, as a Texas Ranger captain, he and his men crossed the Mexican border and ambushed and killed the gang of Rafael Lopez, who had murdered five lawmen in Utah’s worst law enforcement tragedy. Captain Hamer then led the Rangers who tamed the oil boomtowns of Mexia and Borger, and investigated—and solved— some of the most sensational Texas murders of the 1920s.

— Courtesy of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas —

Although a white supremacist of the Jim Crow era, Hamer was sympathetic to black Americans. Beginning in 1908, he saved 15 black men from certain death at the hands of lynch mobs in various towns and cities in east Texas. During the Roaring Twenties, Hamer led an unpopular fight against the Ku Klux Klan in Texas. In 1930, at the courthouse in Sherman in north Texas, Hamer and three of his Rangers held off a mob of 6,000 intent on lynching a black man who had raped a white woman. When the rioters burned down their own courthouse in order to kill the prisoner locked up inside, Frank Hamer became the first and only Texas Ranger to lose a prisoner to a lynch mob. He and his men barely escaped the raging inferno alive. Nonetheless, Hamer’s stubborn refusal to back down against massive odds, and his shooting of two of the Sherman mob leaders, constitute one of the greatest displays of raw courage in the history of American law enforcement.

But to many people in Jim Crow‑era Texas, saving the lives of black suspects really did not matter. Hamer’s actions in Sherman were quickly forgotten. What the public did remember was a much more famous—and by comparison, a much less important—exploit. That was Hamer’s 1934 manhunt for Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. The true story of his manhunt was long muddied by myth, misinformation and unreliable reminiscences from old-timers. Then, in 2006, the voluminous FBI file on Bonnie and Clyde was discovered in Dallas and declassified in 2009. The special agents’ reports described in detail the twists and turns in the Barrow manhunt, and made obsolete much of what had been written before about Frank Hamer’s leading role in tracking down the love‑struck outlaw duo.

— Courtesy Travis Hamer Collection —

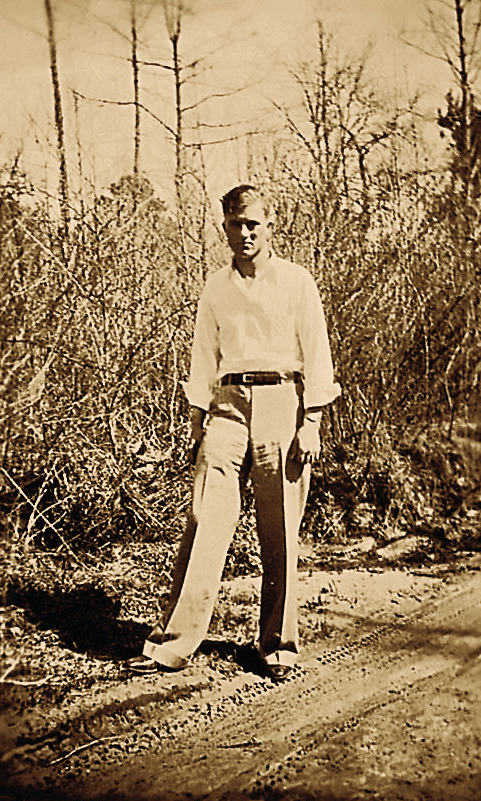

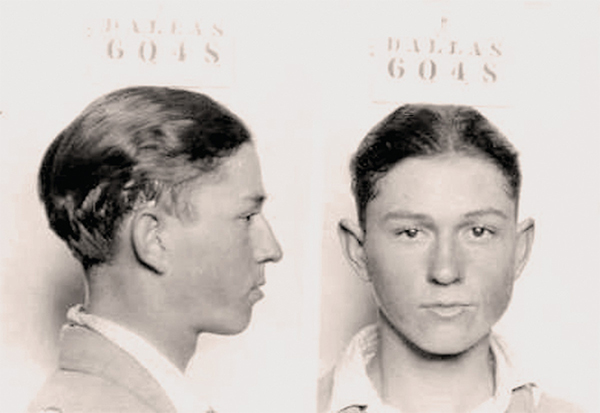

Clyde Barrow was a career criminal who came from a family of criminals: of seven Barrow children, five were convicted felons. According to myth, he was forced by the Depression into a life of crime, but in fact Clyde became a 13‑year‑old chicken thief in 1922, seven years before the Depression even hit Texas. He certainly led Bonnie Parker into a career of crime, but she followed willingly. In myth, she was an innocent girl who never fired a gun. In fact, during a bank holdup in Lucerne, Indiana, Bonnie fired at unarmed citizens. Following a bank robbery in Okabena, Minnesota, Bonnie, Clyde and his brother, Buck Barrow fired at citizens with shotguns and Browning automatic rifles, narrowly missing a school bus full of children. Bonnie shot at lawmen in gunfights at Joplin, Missouri, and Dexter, Iowa. She was, in the popular term of that era, a gun moll.

Former Texas Ranger Hamer joined the manhunt for Bonnie and Clyde on February 10, 1934. By that time the Barrow gang had pulled countless holdups throughout the Southwest and Midwest and murdered nine men—six of them law officers. Despite the fact that he was the best manhunter in Texas, Hamer was then unemployed. A year earlier, the new Texas governor, Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, had fired the entire Ranger force, Hamer among them (Hamer had placed himself on indefinite leave since November), for politicking against her. Then, in January 1934, Bonnie and Clyde engineered a bloody break from the Eastham Prison Farm, killing one guard and freeing several of their gang. Hamer was appointed a special investigator for the Texas Prison System with orders to track down Bonnie and Clyde.

According to legend, Hamer hunted them alone, living and sleeping in his car. That is hardly what happened. A consummate professional, Frank immediately teamed up with Bob Alcorn, a veteran Dallas deputy sheriff who knew Clyde Barrow and had once arrested him. Hamer suspected that Henry Methvin, who had escaped in the Eastham prison break, was riding with the gang. He also knew that Methvin hailed from northwestern Louisiana. Hamer and Alcorn drove to Shreveport where they met quietly with local officers and asked them to be on the lookout for Bonnie and Clyde. Then, on February 19, 1934, they drove west to Arcadia where they met with Henderson Jordan, the rookie sheriff of Bienville Parish, and asked him to watch for the two fugitives.

On February 23, Hamer and Alcorn returned to Texas, and two weeks later Frank visited Huntsville Prison, where he interviewed Hilton Bybee, one of the gang members who had recently been captured. Bybee, who had refused to talk with other officers, made a full confession to Hamer about the gang’s movements. Bybee confirmed that Henry Methvin was still riding with Bonnie and Clyde. Hamer recognized that Methvin might well be the key to locating Bonnie and Clyde. Because Bob Alcorn was then tied up investigating an unrelated bank holdup, Hamer met with the FBI’s special agent in charge of the Dallas office, who assigned agent Edward J. Dowd to work with him. In early March the two officers traveled throughout north Texas, interviewing witnesses and recovering a Ford sedan that Clyde had stolen in Arkansas.

— Courtesy Taronda Schulz Collection —

FBI agents, acting on Hamer’s information, began trying to locate Henry Methvin’s family in Louisiana. They met with Sheriff Henderson Jordan, told him that Methvin was riding with Bonnie and Clyde, and asked him to try to find Ivan “Ivy” Methvin, Henry’s father, whom they believed had recently settled in Bienville Parish. The Methvins were dirt poor and moved frequently, sometimes squatting in isolated cabins and farmhouses. Sheriff Jordan spent the next ten days snooping around the southwestern part of his parish, quietly searching for Ivan Methvin. He finally heard a rumor that Ivy Methvin and his family had been living near Ashland in Natchitoches Parish.

Meanwhile, on Easter Sunday, April 1, Bonnie and Clyde murdered two Texas highway patrolmen north of Dallas. They fled with Henry Methvin to Oklahoma, where five days later they killed a local constable. Clyde, driving by night at high speed in stolen autos, managed to evade a massive, multi-state dragnet. Soon after this, John Joyner, a friend of Ivy Methvin, contacted Sheriff Jordan and asked for a secret meeting with the elder Methvin. Jordan and his chief deputy, Prentiss Oakley, did so, and Methvin offered to give up Bonnie and Clyde in exchange for a Texas pardon for his son. Sheriff Jordan then contacted Louisiana FBI agent Leslie Kindell about the offer. The federal government had no authority to offer a Texas pardon, but Agent Kindell knew that Frank Hamer did. When Kindell, Hamer and Jordan met in Shreveport, Sheriff Jordan recalled, “Hamer agreed that a deal could be offered to the Methvin family. If Ivy Methvin would help capture Bonnie and Clyde, consideration would be given to Henry Methvin. While Hamer did not promise that all charges against Methvin would be dropped by the state of Texas, he came real close to saying that. Before the meeting was over, I came to realize that was the offer that I was to make to Methvin. If he would help capture Bonnie and Clyde, Henry would not have to go back to prison.”

— Photos Courtesy True West Archives —

On April 28, 1934, Hamer, with Alcorn, Agent Kindell and Sheriff Jordan, met secretly in the woods with Ivy Methvin, his wife, two of his sons and his brother. Hamer produced an official letter promising a pardon for Henry Methvin if his family cooperated. The Methvins talked over the offer at great length and finally agreed to accept it. Ivy explained that “no one knows just when Barrow is coming in and he remains only a very few hours and usually does not get out of his automobile.”

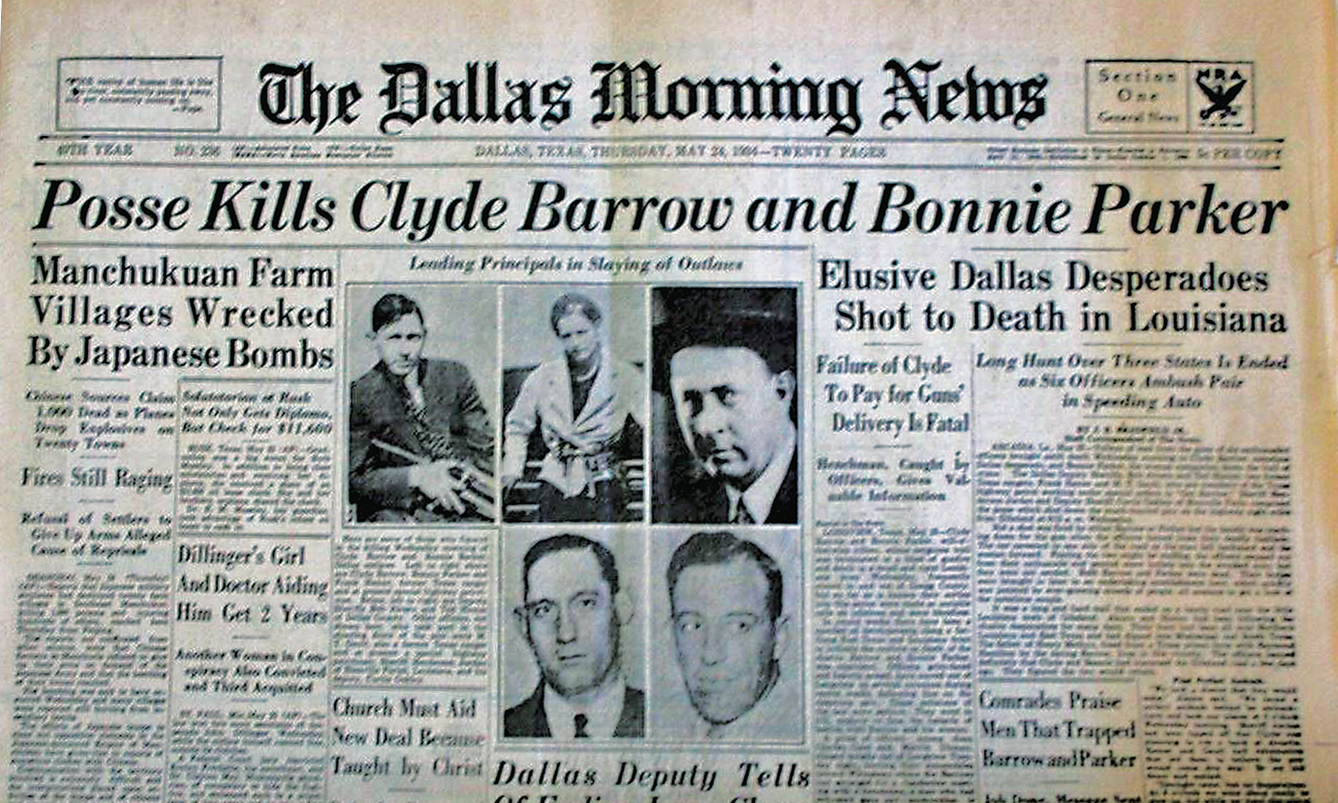

The lawmen had several more meetings with the Methvins. Finally, on the night of May 22, 1934, they got word that Bonnie and Clyde would visit the Methvin house, located near the little crossroads of Sailes, the next morning. Hamer and his men set up an ambush on the highway between Gibsland and Sailes, and waited through the dark morning hours. At nine a.m. Bonnie and Clyde drove up. Within moments their stolen Ford sedan was riddled with 167 bullets and buckshot, and the two lovers passed into outlaw immortality.

John Boessenecker is True West’s 2011, 2013 and 2019 Best Nonfiction Writer of the Year. His most recent book is Shotguns and Stagecoaches: The Brave Men who Rode for Wells Fargo in the Wild West. He adapted “Frank Hamer vs. Bonnie and Clyde” from his New York Times bestseller Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, The Man who Killed Bonnie and Clyde.

The Forgotten Hero

Robert M. Utley’s Version

Why Louisiana Sheriff Henderson Jordan should be remembered as a key member of the hunt and ambush of Bonnie and Clyde.

— All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted —

No knowledgeable Texan doubts that Ranger Captain Frank Hamer deserves the credit for running down and staging the execution of the notorious gangsters Bonnie and Clyde. The story is firmly embedded in the Texas narrative, a highlight of Lone Star history no true Texan would dare challenge.

Throughout the 1920s Hamer—big and muscular, tough, fearless, honest, a man of few words—was the best the Texas Rangers had to offer. Only Tom Hickman came close to Hamer’s record in fighting bank robbers, bootleggers, moonshiners, gamblers, lynchers and corrupt politicians. His signature weapon was not a Colt pistol but the palm of his huge hand, which he cocked at the shoulder and swung in a slap that swiftly downed an opponent.

But during the saga of Bonnie and Clyde, Frank Hamer was not a Ranger captain. The election as governor in 1932 of Miriam A. Ferguson promised a revival of the corruption that had ruled the capitol during the earlier reign of her husband, James E. Ferguson, who could not run because he had been impeached. Everyone knew, however, that “Pa” Ferguson would use “Ma” Ferguson to carry out his own designs. Foreseeing the fate of the Rangers, Hamer resigned a month before her inauguration. On that very day in January 1933, she fired every Texas Ranger and substituted political cronies. Bonnie and Clyde still ran wild.

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were but two of the gangsters who rampaged through the early 1930s. John Dillinger terrorized the entire Midwest, mobilizing lawmen in their most severe challenge and commanding the greatest national publicity. Others included Baby Face Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, Pretty Boy Floyd and Ma Barker. None came near matching the record of John Dillinger. While genuine gangsters (except for Ma Barker), their exploits were exaggerated in later years by J. Edgar Hoover seeking to portray his fledgling Bureau of Investigation (future FBI) as masterful crime-fighters; in the early 1930s they were rank amateurs. Bonnie and Clyde, their trademark an arsenal of high-powered weapons and a sequence of high-powered automobiles, although on occasion swinging murderously through neighboring states, confined most of their killings and robberies to Texas. Few newspapers beyond Texas, preoccupied by Dillinger, paid them much attention.

But the pair, joined at times by other aspiring criminals, constantly eluded Texas lawmen. Especially shocking, on Easter Sunday 1934, as Bonnie and Clyde and their sidekick Henry Methvin lounged in their Ford on a roadside near Dallas, two passing motorcycle patrolmen turned back to investigate. While still astride their cycles, Methvin jumped from the rear seat and emptied a Browning automatic rifle into the first officer, while Barrow emerged from the driver’s seat to blast the second with a sawed-off shotgun.

Less spectacular, another event had already set in motion the operation that would finally snare them. In January 1934 they engineered the escape of three cronies, including Methvin, from the state penitentiary’s prison farm. One guard lost his life in the shootout as the escapees piled into Bonnie and Clyde’s car and sped away.

Angry and chagrined, the director of the state prison system, Lee Simmons, vowed to capture or kill the gangsters. In Austin he persuaded the governors “Ma and Pa” Ferguson to allow him to commission a special officer of the prison system to take on the task. Surprisingly, they concurred in his choice of former Ranger captain Frank Hamer. Bob Alcorn, a Dallas deputy sheriff who could identify the wanted pair, joined Hamer.

The two Texans gained information that pointed to Bienville Parish in northwestern Louisiana. In the parish seat of Arcadia, they discovered that Sheriff Henderson Jordan had already located one of Bonnie and Clyde’s hideouts and had been handed an opportunity that might trap them. Henry Methvin’s parents moved from Ashland to Gibsland, and the gangsters frequently hid there. Through an emissary, Methvin offered to betray his comrades. With a signed promise from Governor Ferguson to pardon him for all crimes committed in Texas if the plan succeeded, he would alert the sheriff when Bonnie and Clyde took refuge near Gibsland. Frank Hamer journeyed to Austin and returned with the signed document. The intermediary passed it on to Henry Methvin.

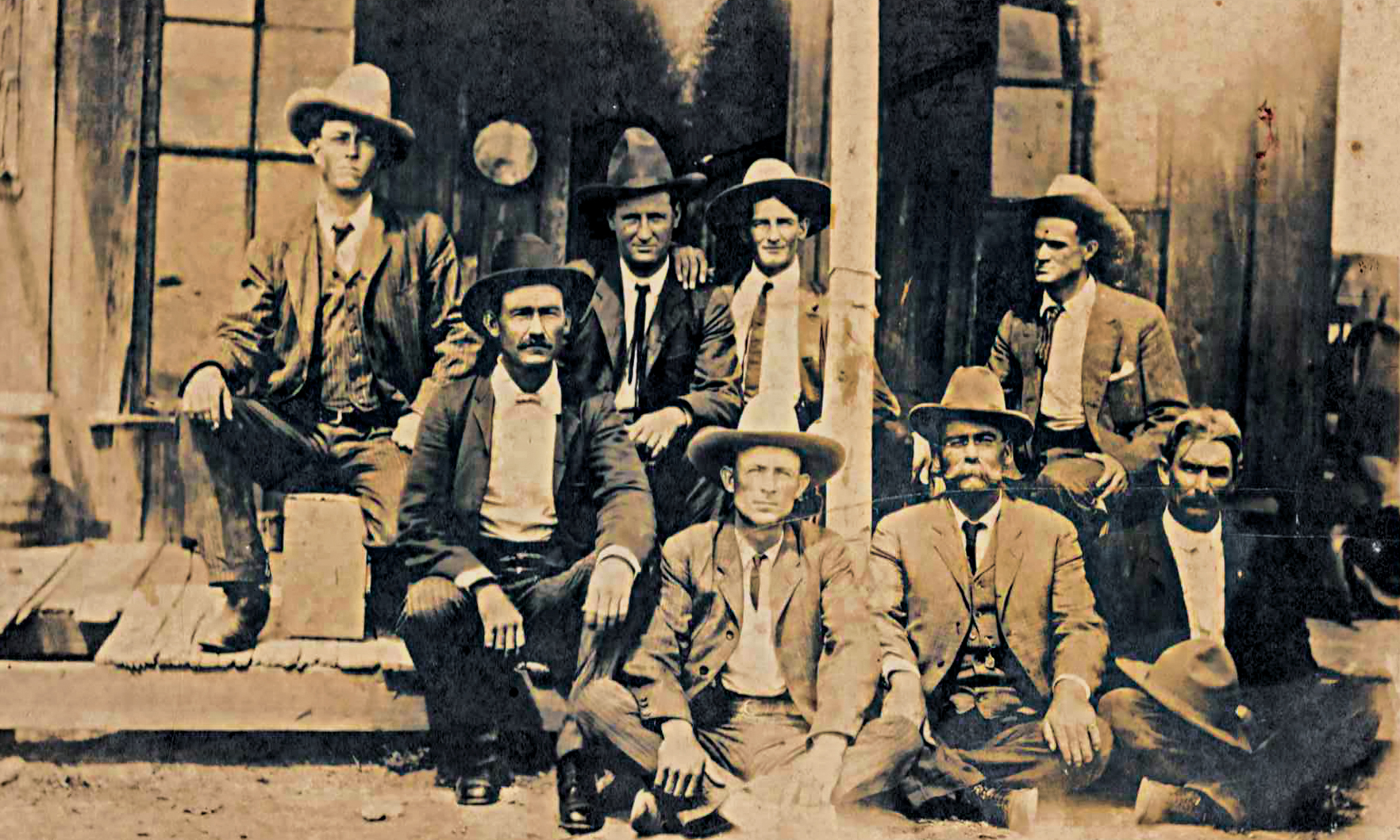

As the weeks passed, the task force expanded. The murder of the Texas highway patrolmen on Easter Sunday prompted State Patrol Chief Louis Phares to insist on a role in the hunt. Hamer chose a former Ranger colleague, B. M. “Maney” Gault, whom Chief Phares commissioned in the highway patrol. Another Dallas deputy, Ted Hinton, joined the team. With Sheriff Jordan and one of his deputies, Prentis Oakley, the posse numbered six.

The four Texans waited impatiently in a Shreveport motel. Not until May 21 did they get word that Bonnie and Clyde were at Ivy Methvin’s hideout outside of Gibsland, near the crossroads of Sailes. Methvin would give them the slip in Shreveport. They had agreed that if accidentally separated, they would rendezvous at the abandoned farmhouse hideout. Armed with BARs, shotguns and Colt automatics, the six lawmen positioned themselves behind brush at the side of a gravel road leading through heavily forested land to Gibsland. Methvin’s father parked his logging truck across the road and would feign a flat tire.

On May 23, after two nights and a day in the brush, the officers agreed that they’d waited in vain and prepared to leave. The high whine of a speeding Ford V-8, however, alerted them to the approach of the culprits. Methvin’s father played his part, and the Ford eased to a stop beside his truck. An approaching timber truck prompted Clyde to make room for it by steering his vehicle to the front of Methvin’s truck. Deputy Oakley, anxious not to lose the target, fired two rounds from his BAR. The others opened with all the weapons they had, shredding both car and occupants for the enduring images that splashed the front pages of newspapers everywhere and remain indelibly fixed in gangster lore.

— Courtesy Toranda Schulz Collection —

Bonnie and Clyde died by the very weapons they treasured and had packed into the death car. Two months later, accompanied by a woman in a red dress, John Dillinger emerged from a Chicago theater into a hail of bullets that ended his career. The era of the big-time gangsters drew to a close.

Frank Hamer returned home to public acclaim. Newspapers and magazines hailed him as the man who had run down Bonnie and Clyde and organized the ambush that ended their crime spree in a shower of blood and shattered glass. He was a hero to all Texans and remains so to this day.

Scholarly support came from the respected historian Walter Prescott Webb, whose history of the Texas Rangers appeared a year later. He confined his narrative of Bonnie and Clyde to the words of Hamer himself, interviewed within months after the ambush. As Webb later conceded, it was an interview cobbled together from handwritten notes scrawled on cards as he talked with the legendary captain. With people and places still to be protected, Hamer talked vaguely, with little explicit detail, and at times misleadingly. Yet the “interview” remains the authoritative account in a book that has never been revised or gone out of print.

Sheriff Henderson Jordan, however, was the true architect of the scheme. He located the hideout, received the offer of betrayal from Henry Methvin’s emissary and organized the ambush. Hamer is entitled to credit for acting as a messenger to Governor Ferguson and for participating with the five others of the posse in gunning down the fugitives. He did not track down Bonnie and Clyde.

Tell that to a Texan.

Award-winning author Robert M. Utley is the author of Lone Star Justice: The First Century of the Texas Rangers and Lone Star Lawmen: The Second Century

of the Texas Rangers.

The Legendary Maney Gault

John Fusco’s Version

Frank Hamer’s best friend and partner in tracking down Bonnie and Clyde should be remembered as one of the greatest Texas Rangers.

— All images Courtesy John Fusco unless otherwise noted —

White Rabbit

On April 1, 1934, 6’2” Frank Hamer was sitting, cramped, in his tiny Ford V-8 automobile in a lonely riverside migrant camp near the West Dallas viaduct, eating from a can of sardines and celebrating Easter Sunday alone. Or maybe he had driven home to Austin and was having a home-cooked dinner on Riverside Drive with his wife and kids, a periodic respite from his dogged and highly secretive multistate hunt for the natural-born killers known as the Barrow Gang. We don’t know—and we will never know—because part of Frank Hamer’s success as a Texas Ranger and manhunter was that he was intractably unwilling to talk.

What we do know, is that on that Easter Sunday, two highway patrol officers were out on motorcycle patrol near Grapevine, Texas. Somewhat relaxed on Easter morning—and woefully untrained—they came across a vehicle parked on the side of the road, as if disabled. A tiny but well-dressed young male and petite young female were loitering nearby. Both had gimped legs and paced nervously. The little red-haired girl was holding a white rabbit. An Easter bunny. The kids seemed as if they were stuck roadside and needed some help.

Nearby, farmer William Schieffer, who had observed the young couple “kissing and petting” all afternoon while the white bunny hopped about and grazed, was hauling rocks by the edge of the road when he witnessed the jarring barrage of automatic gunfire. The “little girl” gimped up to a downed and dying young cop and fired a point-blank kill-shot to his head from a sawed-off 20-gauge. There was laughter, and something said by the female that sounded like “Ya’ll see that? His head bounced like a rubber ball!”

Officer Wheeler was 23, on his first day assigned to motorcycle patrol. He did not have shells in his shotgun because he was concerned that if he “took a spill,” the gun might discharge and harm bystanders. He was to be married 11 days later; his fiancée wore her wedding gown to his funeral. She went to her grave in her 90s, cursing the glorification of Bonnie and Clyde—especially the 1967 movie.

The brutal double murder at Grapevine was a major turning point in the highly publicized pursuit of “Barrow and Bonnie.” Up until that Sunday, the self-promoting lovebird killers had been enjoying public fascination, a near-worship fueled by the Great Depression and a desperate public hunger for distraction and flashy anti-heroes. This brazen killing was also the urgent juncture at which Frank Hamer, a lone hunter from an earlier era of horse and Winchester, sought out a partner to join him on the hunt.

Hamer had been working in loose consort with Dallas Sheriff Smoot Schmid, Dallas Deputy Bob Alcorn, Deputy Ted Hinton and a few committed agents from Hoover’s prototype agency for the FBI (even as Hoover resented having an aging legend like Hamer on the case); but now Hamer specifically asked for a partner from his former Texas Rangers days, an old-school lawman he could count on—a former Ranger named B.M. “Maney” Gault.

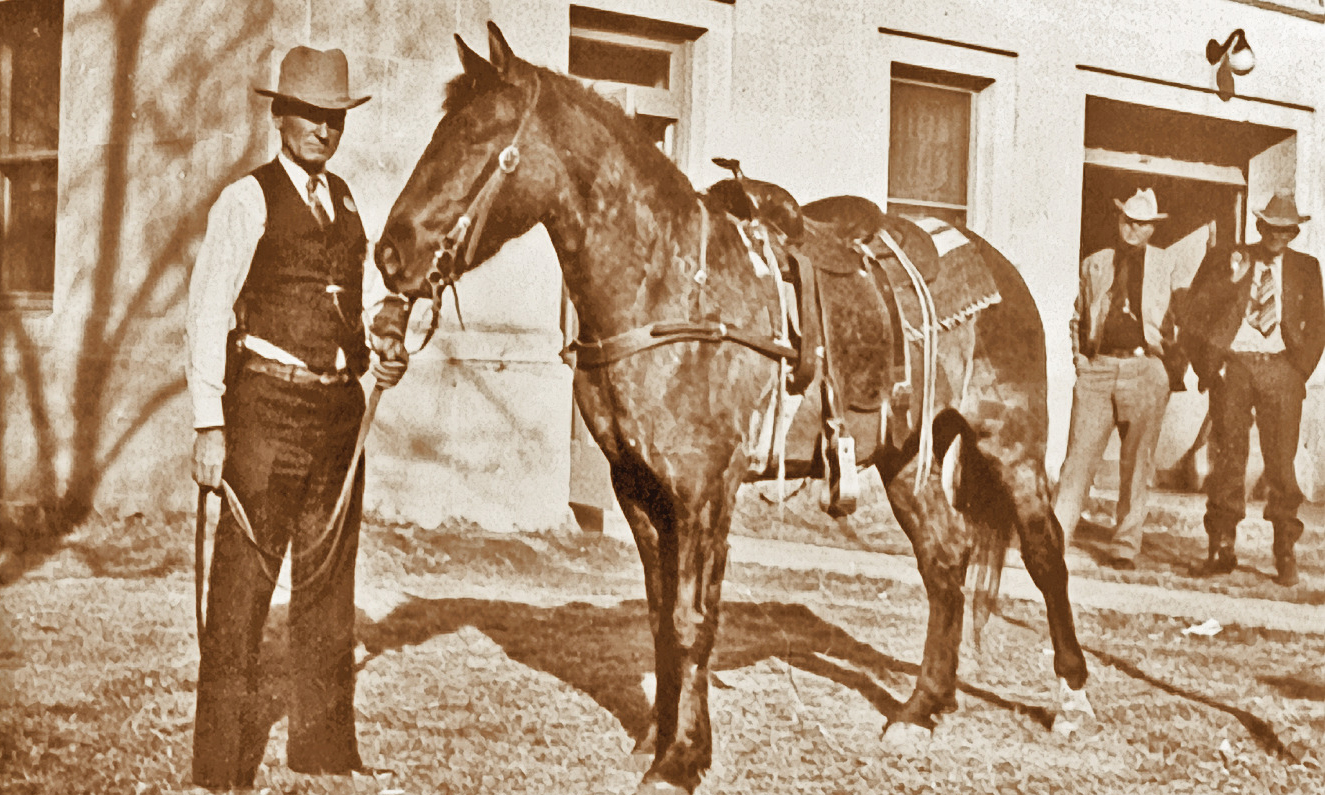

Neighbors

Frank Hamer had known Maney Gault since the mid-1920s, when they were neighbors in Austin. The diminutive, steely-eyed Gault had been a stock and dairy farmer until crashing milk prices forced him to find work in a sawmill. Regardless, he was a man after Hamer’s own heart—laconic, loyal, modest, conservative, sardonic and perfectly unbreakable. Hamer appreciated the fact that Maney was from a “Travis County pioneer family.”

As neighbors in the Riverside area of Austin, Hamer and Gault became tight, as did their feisty wives, Gladys and Rebecca. The late Frank Hamer Jr., a preteen then, remembered Gault being as “smooth as satin with a pistol,” but also proficient on the guitar. Captain Hamer was also a competent hill country fiddler, and the two spent many a night playing cards or dominoes, blue grass music, and sharing terse, wry, Texas-style stories. Gladys Hamer had a parrot in a cage who repeated every damn thing a body said; Frank had a pet javelina named Porky who had free run of the house. It was a lively time on Riverside Drive. Hamer, whom Gault called “Pancho,” was a casual and careful sipper while Maney “enjoyed his whiskey” and both were known to “cuss up a storm,” much to the amusement of young Frank Jr., who came to think of Maney Gault as an uncle.

This was years before Gault joined the Texas Rangers, but Hamer was already using his friend and neighbor for specialized undercover work. Maney might have been a cow man and mill worker, but Hamer recognized in him the ability to blend in and “talk his way through,” his lack of fear and the principled moral compass that Hamer valued above all else. He could also kick ass—literally, on more than one occasion. Hamer privately put his friend Maney underground during the rough-and-tumble days of Prohibition, illegal gambling and in lawless oil boomtowns like Mexia and Borger.

The Dust Bowl

As the Great Depression grew near and private sector jobs dried up—even the sawmills—Hamer offered his friend a job in the Texas Rangers Headquarters Company. Hamer and Gault now began to team together in earnest, particularly in the violent Jim Crow climate when African-American men were frequently lynched before due process and trials. Gault was likely among the handful of Rangers who stood with Hamer when he protected a black rape suspect from a lynch mob of 6,000 in Sherman, Texas. As senior captain, Hamer was leading the fight in Texas against the Ku Klux Klan.

Hamer and Gault worked seamlessly together as Rangers up until Miriam “Ma” Ferguson was re-elected as governor of Texas. Hamer and the Rangers had sup-ported rival Governor Ross Sterling, so when the truculent “Ma” won, she fired every Ranger (that is, those who had not already resigned in protest like Hamer and Gault) for their partisanship. Texas became a haven for lawless types, from Machine Gun Kelly to the Barrow Gang. Ma Ferguson was known for generously granting furloughs to prisoners, issuing more than 4,000 pardons during her two non-consecutive terms as governor.

While Gault found work with the Texas Highway Patrol, Hamer took on sporadic detective and security assignments. That’s what he was doing when when Lee Simmons, head of the Texas Prison System, recruited Hamer to hunt down the Barrow Gang.

End of the Trail

By April 14, 1934, Frank and Maney were back together—this time as Highway Patrol officers—sharing the cramped space of Hamer’s Ford and hunting down the notorious killers. Like their quarry, they slept in their car, drove 500 or more miles per day, and mostly lived on crackers and sardines. According to the late Frank Jr., they took guitar and fiddle with them—along with modern firepower.

So it was, that more than a month later (102 days all-in for Hamer), Hamer, Gault, Alcorn, Hinton (the Dallas cops needed to make the positive ID on the criminals), Louisiana Sheriff Henderson Jordan and his Deputy Oakley caught Barrow and Parker in their own pattern of running and put an end to the multistate menace that had left nine lawmen and four innocent civilians dead.

— True West Archives —

Maney Gault fired his share of rounds on that legendary, controversial and much misunderstood morning. To the very last moment, he was covering his friend Pancho in the silent aftermath when he was reported as yelling “Careful, Cap, they might be possum’n!”

Soon after Ma Ferguson left office, the Texas Rangers were reconstituted into a new state law enforcement agency called the Texas Department of Public Safety. It can be argued that Hamer and Gault had saved the Rangers even as they embarrassed J. Edgar Hoover (it is said that Hoover was livid when Hamer offered to go get Dillinger next).

The Austin newspaper ran a front page headline proclaiming: “HAMER-GAULT HERO DAY IS SET.” Citizens planned a testimonial dinner to be held for Frank and Maney on May 28th, with a speech by the governor. Frank and Maney rejected any such celebration. Other than an interview given to Walter Prescott Webb years later, Hamer only gave one interview at the time, to a reporter he knew and trusted, and Gault gave none. When rejected by Gault, one reporter described the former Ranger as “cold-eyed, mysterious, and he doesn’t talk.” Hamer turned down a $10,000 offer to have a book written about him and major movie offers, including one from Tom Mix. He returned to his wife, Gladys, and his quiet and modest work in oil security. Gault, however, returned to the Texas Rangers, serving as sergeant in Austin.

Not long after the ambush of Barrow and Parker, the bullet-pocked death car reappeared in public. A local carnival operator named Charles Stanley purchased the mangled vehicle from its original owners and took it on tour under his new billing as The Crime Doctor. For a time, he even had Barrow’s and Parker’s parents and other relatives on the road with him, making some cash off their deceased children.

At an appearance in Austin, as Stanley showed off the Death Car, presented gruesome slides of photos and spoke openly about Hamer’s confidential sources, two figures approached from the packed house. Frank Hamer and Maney Gault came up on stage and confronted the carney. With the diminutive but steely-eyed Gault on one side, Hamer slapped Stanley in the head, confiscated the slides and threatened him with more serious action if he continued his side show.

Within five years, Maney Gault was promoted to Captain of C Company in Lubbock. His territory covered some 94 counties in west Texas, extending from the Panhandle to the Rio Grande. During the 10 years he served as captain, Gault solved many cases involving murder, bank robbery and cattle rustling.

Some say that Gault was a dogged lawman to the detriment of his own health. At 61, he was still working on an unsolved murder, when he fell ill. He would die on December 4, 1947, in Austin. Hamer eulogized him as “a 23-karat fellow. He was as loyal a man as there ever could be. Never a better man or truer friend than Maney Gault.”

The Highwaymen

Three-time Academy Award nominee Woody Harrelson had wanted to play the role of B.M. “Maney” Gault for more than ten years. While most actors, from Robert Redford to Tommy Lee Jones to Liam Neeson, wanted to portray Frank Hamer, Woody was greatly drawn to Maney Gault. It should be mentioned that so was Paul Newman before he became ill.

While historical information on Gault is spare, Harrelson was fascinated by a story about an oil boomtown that once requested the Texas Rangers’ service. “Some guy came into this town and was just terrorizing people,” says Harrelson, a Texan himself. “The Rangers sent one guy, Maney Gault, to deal with this whole group. The gang leader was inside a barn, so after clearing it of civilians, you hear all this crashing and everything, and then Maney comes out, holding the guy by the back of the shirt, just kicking him in the ass all the way down the street!”

— Courtesy Netflix —

While the movie character is true to the spirit of Maney Gault, creative license almost always needs to be employed in creating a historically based drama. In the case of The Highwaymen, and with full disclosure, some character traits were borrowed from some of Frank Hamer’s other Ranger allies, in the interest of portraying the old-time Ranger ethos that made the pursuit of Bonnie and Clyde thematically unique and emblematic of putting old-time Texas Rangers on the trail of modern-day gangsters.

While Frank Jr. recalled that Maney liked his drink (bourbon, he told me), the filmmakers and Woody Harrelson took this idea deeper and darker to reflect the moral complexity of violence and how some on the front lines “drink to forget.”

It should also be pointed out with clarity that during the pursuit of Bonnie and Clyde, Frank Hamer wanted one man and one man only; that was Maney Gault—one of the Rangers who had resigned in protest alongside Hamer when Ma Ferguson was reelected—and Hamer personally sought him out.

Other pieces of the character composite were inspired by Texas Rangers like Dan Hines and Leo Bishop, Rangers who served during the Great Depression because

of dire economic circumstances; they

had been living in poverty. Historically, while Gault may have been forced, at one point, to find work in a sawmill when the stock and dairy industry suffered, he

was supporting his wife, Rebecca, and their two children through stellar employment with the Texas Highway Patrol.

As Capt. Frank Hamer is finally being introduced to the public as the true hero in the Bonnie and Clyde story—and not the mustache-twirling villain from the 1967 movie—Capt. Maney Gault should also go down in history as one of the reluctant heroes on that day, and one of the greatest Texas Rangers of all time.

Screenwriter John Fusco’s most recent screenplay chronicles Frank Hamer and Maney Gault’s manhunt of Bonnie and Clyde in the Netflix film The Highwaymen, which debuted in theaters March 29, 2019. He was the recipient of True West’s 2019 True Westerner Award.