“The five men rode boldly and at a swinging trot, raising a cloud of dust which literally enveloped them as they passed down Eighth Street.” –An eyewitness

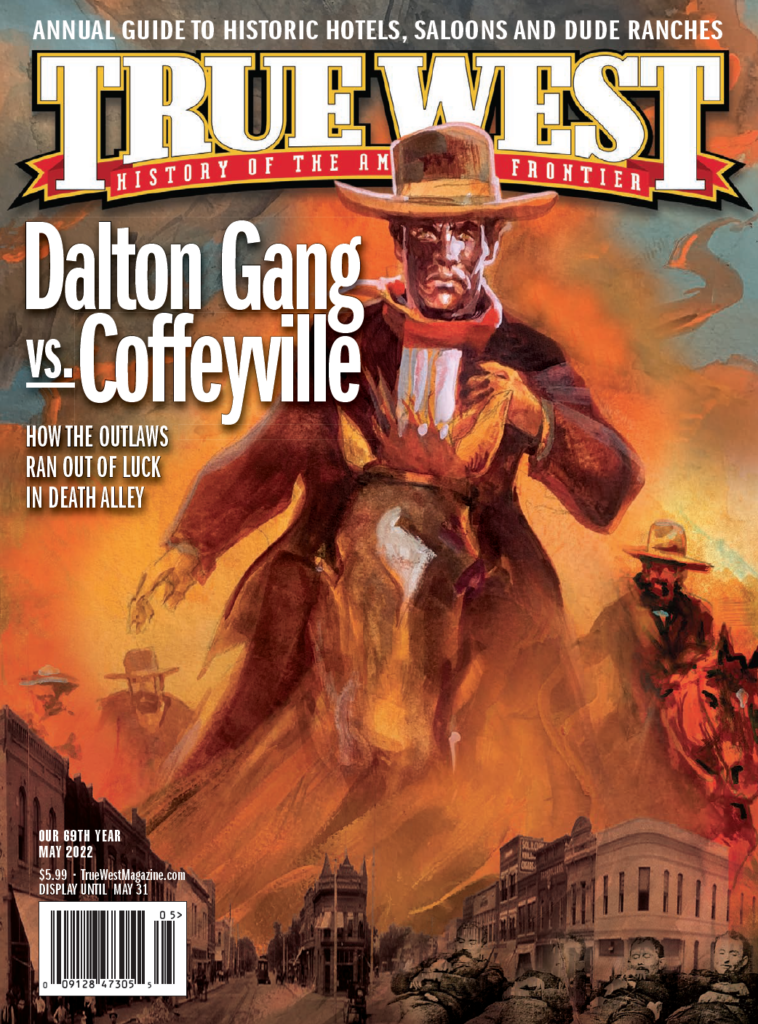

For a brief period toward the end of the 19th century, the mere mention of the name “Daltons!” was enough to send paroxysms of terror through the towns of the Frontier West. Ruthless to a fault, they robbed and murdered at will, outwitting or outrunning hundreds of law enforcement officers—until the crisp October day in 1892 when a group of citizens, in defense of their town, their money and their lives, brought them down in a flurry of gunfire.

Indian Territory in the 1870s and ’80s—all 74,000 square miles of it—was a sinkhole of criminal activity. Bootleggers and whiskey runners sold illegal rotgut to the Indians; highwaymen robbed with abandon; and deaths by gunfire were frequent, and often unpunished. Further exacerbating the situation, gangs and individuals who had committed felonies in the States often crossed into “the Nations,” as the territory was more familiarly known, seeking to evade the law’s reach by losing themselves in its vastness. Only a small number of deputy marshals, riding out of “Hanging Judge” Isaac C. Parker’s court in Fort Smith, were assigned the impossible task of keeping order.

By the early 1890s, most of the infamous miscreants from other parts of the so-

called Wild West—Jesse James, Billy the Kid, Clay Allison, Cole Younger—had met bloody ends, or were securely behind bars. Still, the Nations continued turning out badmen in sufficient numbers to keep the marshals busy.

Of these, the most notorious by far was the Dalton Gang. They would ride out of their various hideouts in the Nations, terrorize the citizens of Kansas, Texas, New Mexico and pre-statehood Oklahoma, and rob trains and banks with abandon. The gang was a loosely structured band of brigands, the numbers fluctuating as members came and went. At various times, it included such larcenous luminaries as “Bitter Creek” Newcomb, “Black-Face Charlie” Bryant (a near-miss pistol shot had permanently powder-burned his face), “The Narrow-Gauge Kid,” Bill Powers, Dick “Texas Jack” Broadwell and the redoubtable Bill Doolin.

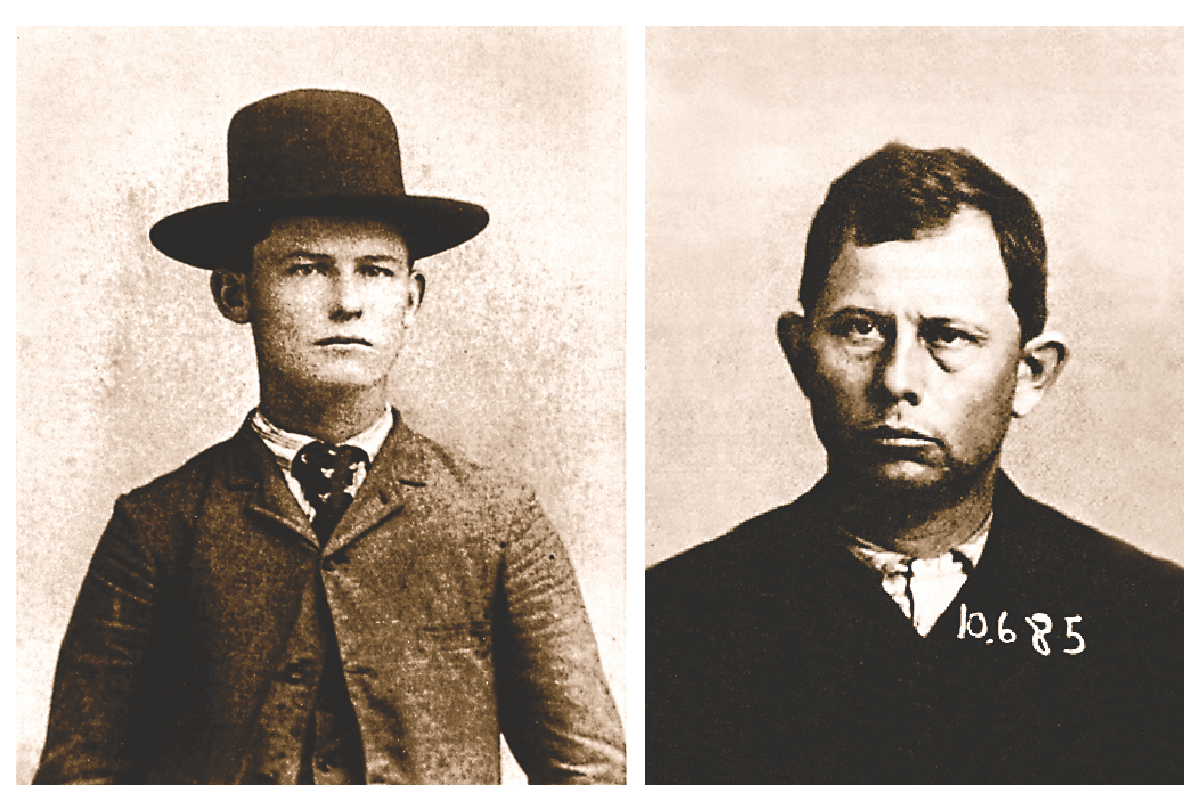

The core of the gang, however, were three Dalton brothers—Grat, Emmett and the gang’s leader, tall, handsome Bob. A fourth brother, Bill, “rode the outlaw trail” as well, but he only occasionally accompanied his brothers, preferring to work out of Oklahoma and his home state of California.

The three boys were born in Cass County, Missouri, to Lewis and Adeline Dalton, on land left to Adeline by her father. Although she was a member of the notorious Younger family of outlaws, she was never known as anything but respectable and hard-working. Lewis, however, was a fiddle-footed ne’er-do-well, and often left Adeline to provide for the family.

After producing 15 children, the couple separated, and even before Lewis died in 1890, Adeline was raising her large brood on her own. By all reports, she was a kind and diligent mother, and a good provider. One older boy, Frank, served as a deputy marshal, and—as were so many who wore the badge for Judge Parker—he was killed in the line of duty, while shooting it out with a band of horse thieves. Eventually, Adeline would live to bury four of her sons who had died of gunshot.

Bob, Grat and Emmett briefly tried their hands at law enforcement, and found the job provided an ideal opportunity to pilfer, sell whiskey to the Indians and generally disgrace the office. Inevitably, they were fired, and immediately turned their attention to outright banditry.

Gang of Thieves

Robert Reddick “Bob” Dalton was clearly meant to be the leader. In 1890, 22-year-old Bob—clever, ambitious, and a noted marksman—organized the band of brigands that would become known throughout the West as the Dalton Gang. All evidence points to the fact that older brother Grat, described by one biographer as having the “heft of a bull calf and the disposition of a baby rattlesnake,” was the slowest of the three, or as another historian puts it, “downright dense.” For his part, youngest sibling Emmett idolized his big brothers, and followed them sheeplike on whatever high jinks Bob concocted.

On their first outing as a gang, they rustled three horse herds in the Nations, and sold them in Kansas, just a few jumps ahead of a posse of Judge Parker’s deputy marshals. They would soon graduate to train and bank robbery, leaving the occasional corpse in their wake. Soon, significant rewards were posted for their capture, motivating such intrepid lawmen as Deputy Marshal Heck Thomas and Wells Fargo’s Fred Dodge to doggedly pursue the gang.

Then Bob allowed hubris to direct his plans. It needled him that the now-defunct James Gang had grown to legendary status, and he formed a plan to surpass their boldest deeds. He would rob two banks at one time, a feat that Frank and Jesse never dared attempt, and he chose Coffeyville, Kansas, as his target.

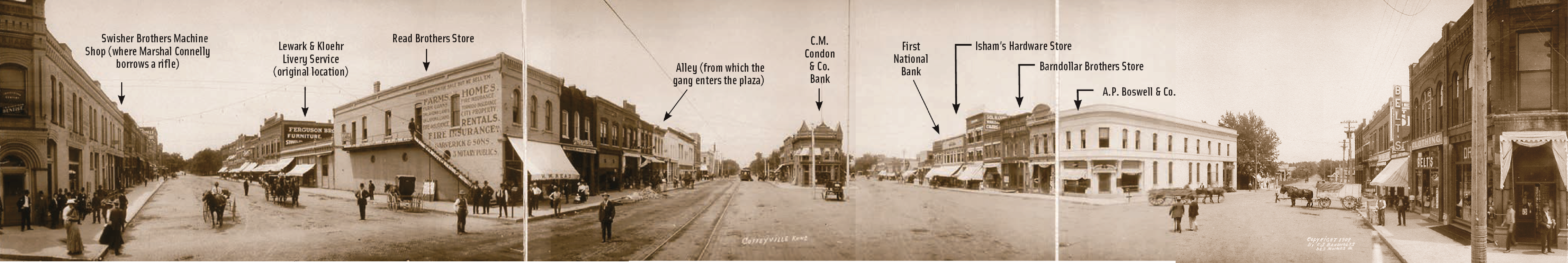

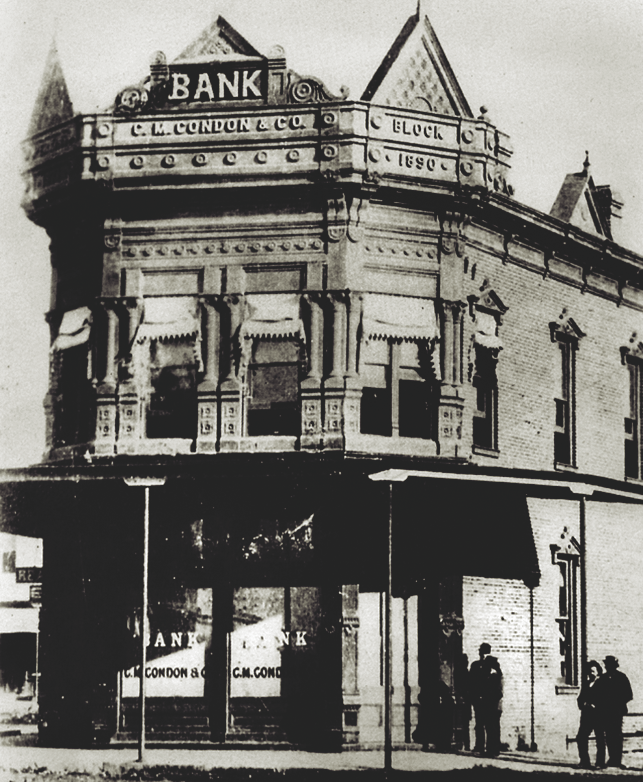

The Dalton family had lived near Coffeyville for a time when the boys were very young. The town’s two banks, diagonally situated from one another across a plaza at the V-junction of Union and Walnut streets: The First National, and the impressive two-story red brick Condon. Since the brothers were familiar with the town, the choice seemed ideal. Selecting Bill Powers and Dick Broadwell to accompany them, they saddled and rode for Kansas.

Fatal Decision

The Coffeyville of 1892 was a far cry from the wild saloon and gambling mecca of its trailhead days of two decades earlier. It was now a respectable, bustling community that catered to farmers and businessmen, as well as cattlemen and cowboys, and contained several mills, a cheese factory, barber shop, livery stable, and family restaurants. It also boasted drug, hardware, lumber, dry goods, blacksmith, and shoe stores. In fact, years earlier, Adeline had bought shoes for her boys at the shop of George Cubine.

On the morning the Daltons chose to rob Coffeyville’s two thriving banks, an urban development project was well underway to add curbs and gutters to the street fronting the banks. As a result, the street had been torn up, and all the hitching posts—including the one nearest the banks, where the gang had planned to tie up their horses for a fast getaway—had been removed. Although at the time this seemed like a minor inconvenience, it would soon prove to be a grave—and fatal—mistake.

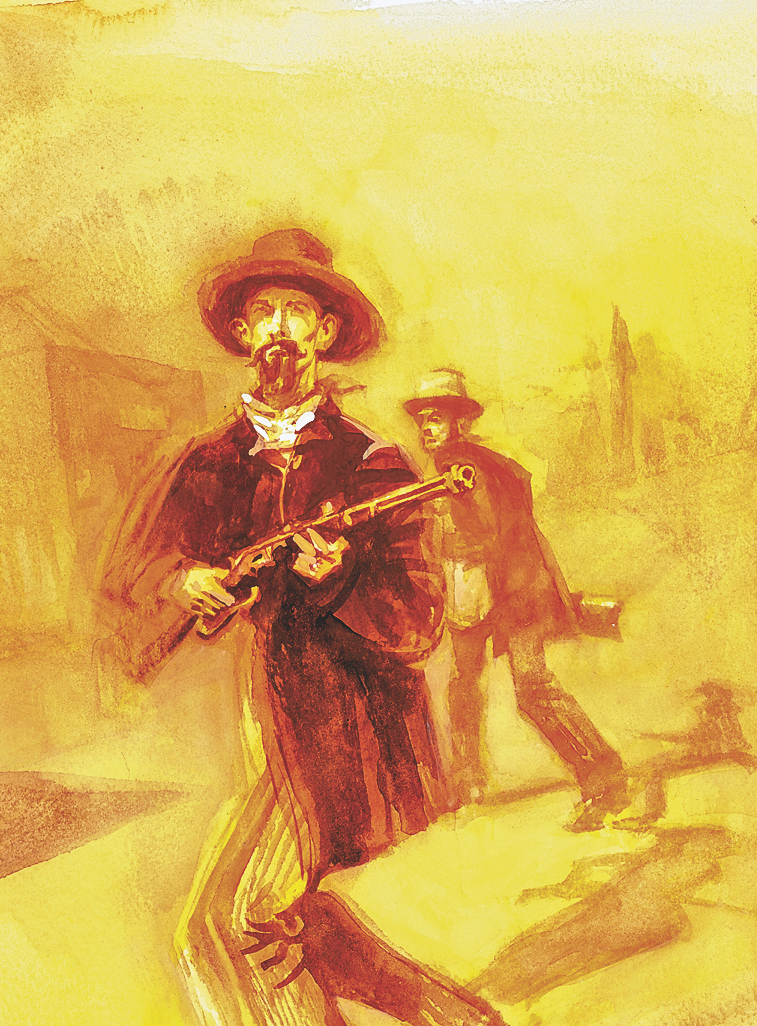

Because the Daltons were known to several of the townspeople, they rode into Coffeyville wearing false beards and sideburns. All five men were heavily armed; in a display of pre-victory largesse, Bob had bought each of them a pair of factory-engraved, pearl-handled .45-calibre Colt revolvers. He himself carried three pistols. But it was their Winchester repeating rifles that would play a deadly part in the drama that was about to unfold.

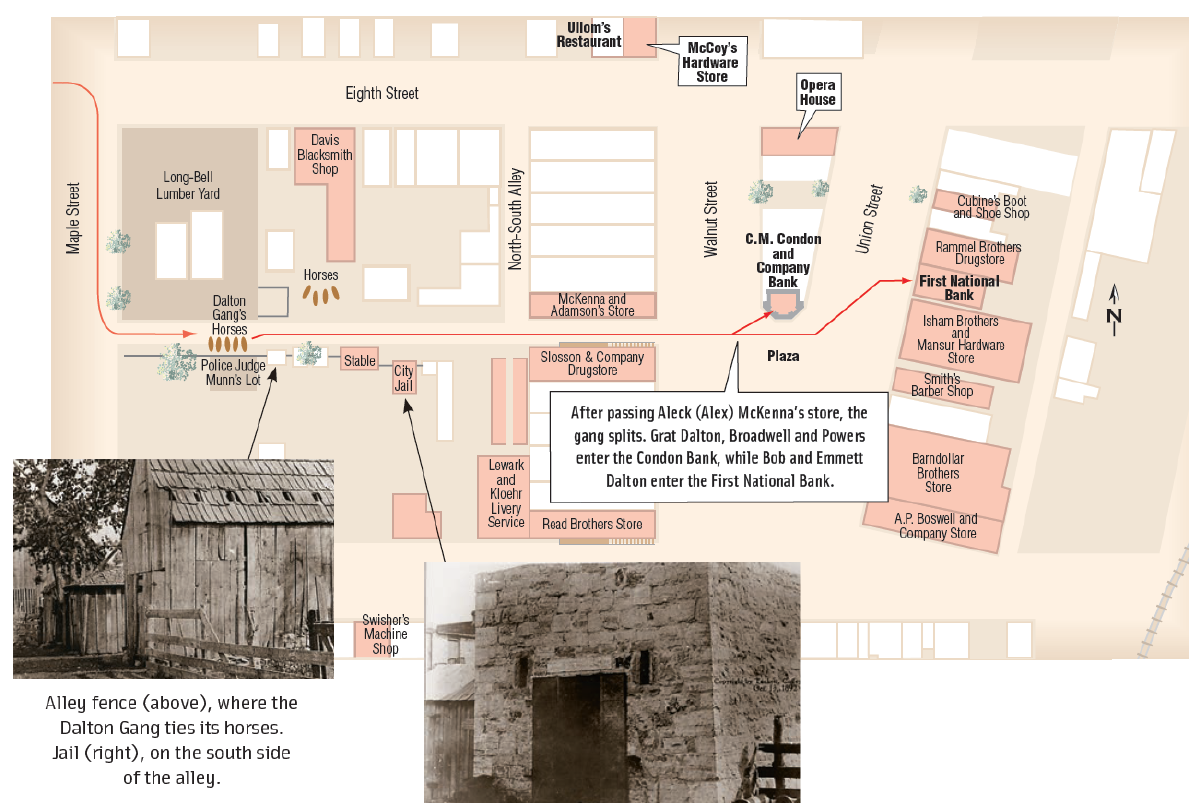

When they found the street devoid of hitching rails, the five rode into a narrow passageway behind several buildings and tied up to a wooden fence. This unremarkable stretch of ground would soon earn the grisly and accurate epithet, Death Alley.

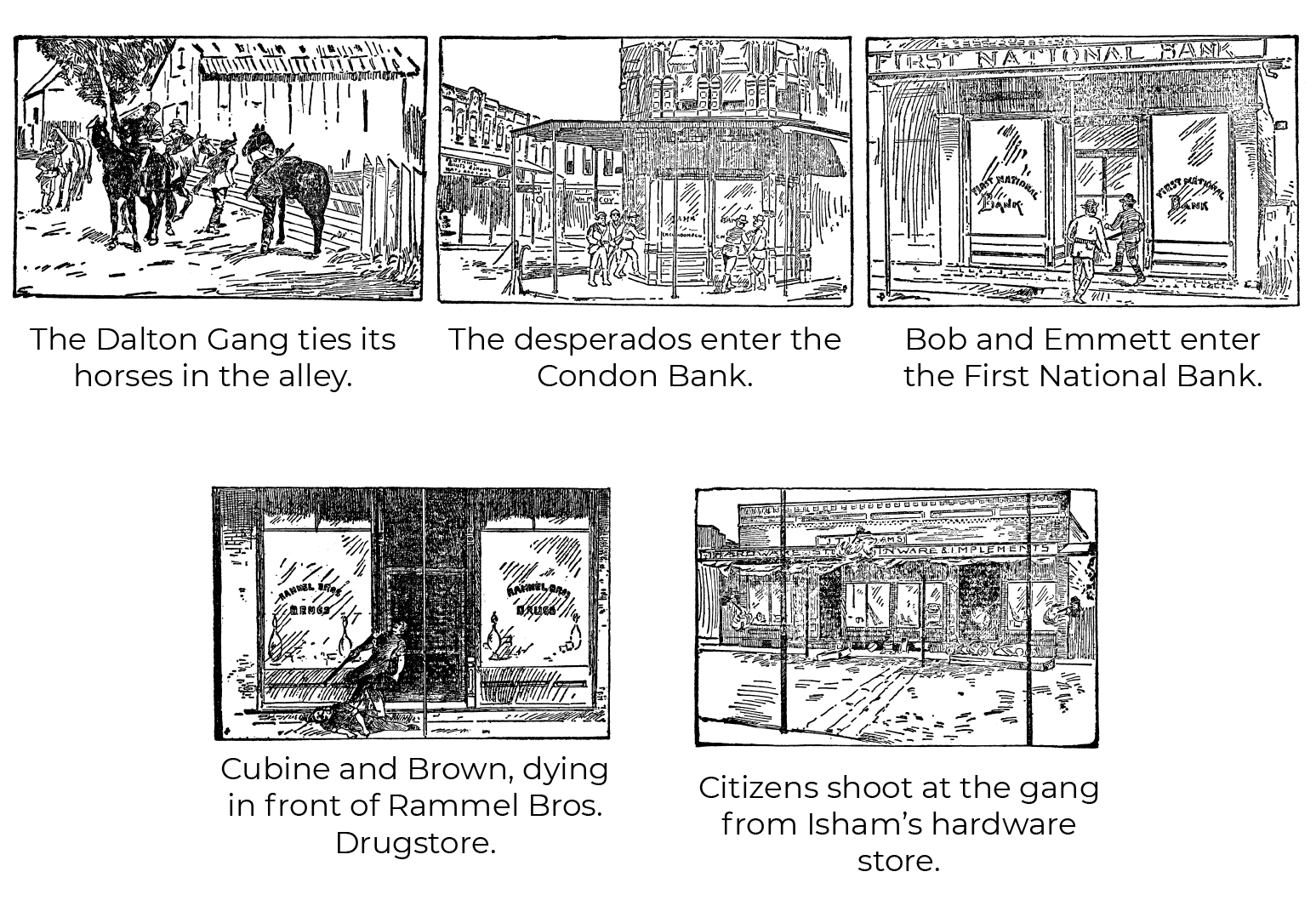

The outlaws were now well over one hundred yards from their two objectives, across an open plaza. Unlimbering their rifles, they divided into two parties. Grat, Powers and Broadwell entered the Condon Bank, while Bob and Emmett, still wearing their crude fake whiskers, strode into the First National. It was around 9:30, and the streets outside the banks were growing increasingly busy with foot, horse and wagon traffic.

At first, no one paid them any mind; it was hunting season, and the sight of men carrying rifles in town was not uncommon. Then, dry goods merchant Aleck McKenna, who was familiar with the brothers, recognized Grat as he crossed the plaza. McKenna watched as the five split up, carefully following Grat and his two cohorts as far as the outside of the Condon Bank. Peering through a large plate-glass window, he observed one of the men leveling his rifle at the clerk.

The gang no longer possessed the element of surprise, as McKenna set about raising the alarm. Men immediately dropped what they were doing, and either grabbed their own weapons or rushed to Isham’s Hardware Store, where the proprietor was handing out firearms and ammunition. Citizens took up positions around the plaza, sighted in on the banks, and waited.

Inside the banks, things were not going well for the would-be robbers, who were completely unaware of the reception being prepared for them just outside the doors. After cashier Charles Ball filled a grain sack with money from the counter and cash drawer, Grat demanded that he open the vault. Displaying incredible presence of mind, Ball ran a dangerous bluff; he told Grat that the vault was on a time lock and would not open until 9:30. When Grat asked what time it was, Ball pretended to consult his watch and responded that it was only 9:20.

Ball was risking his life to save the bank’s funds. Had any of the three badmen looked up at the large wall clock, they would have seen that it was 9:40, and the vault was already open. Still unaware of the flurry of activity outside, Grat—in a stunning display of what one chronicler labelled his “glacially slow wit”—decided to wait.

Meanwhile, in the First National Bank, bookkeeper Bert Ayers—despite Bob’s repeated threats to shoot him—was responding to the outlaw’s demands as slowly as possible. And when Bob ordered Ayers to open the safe, he answered that he didn’t know the combination.

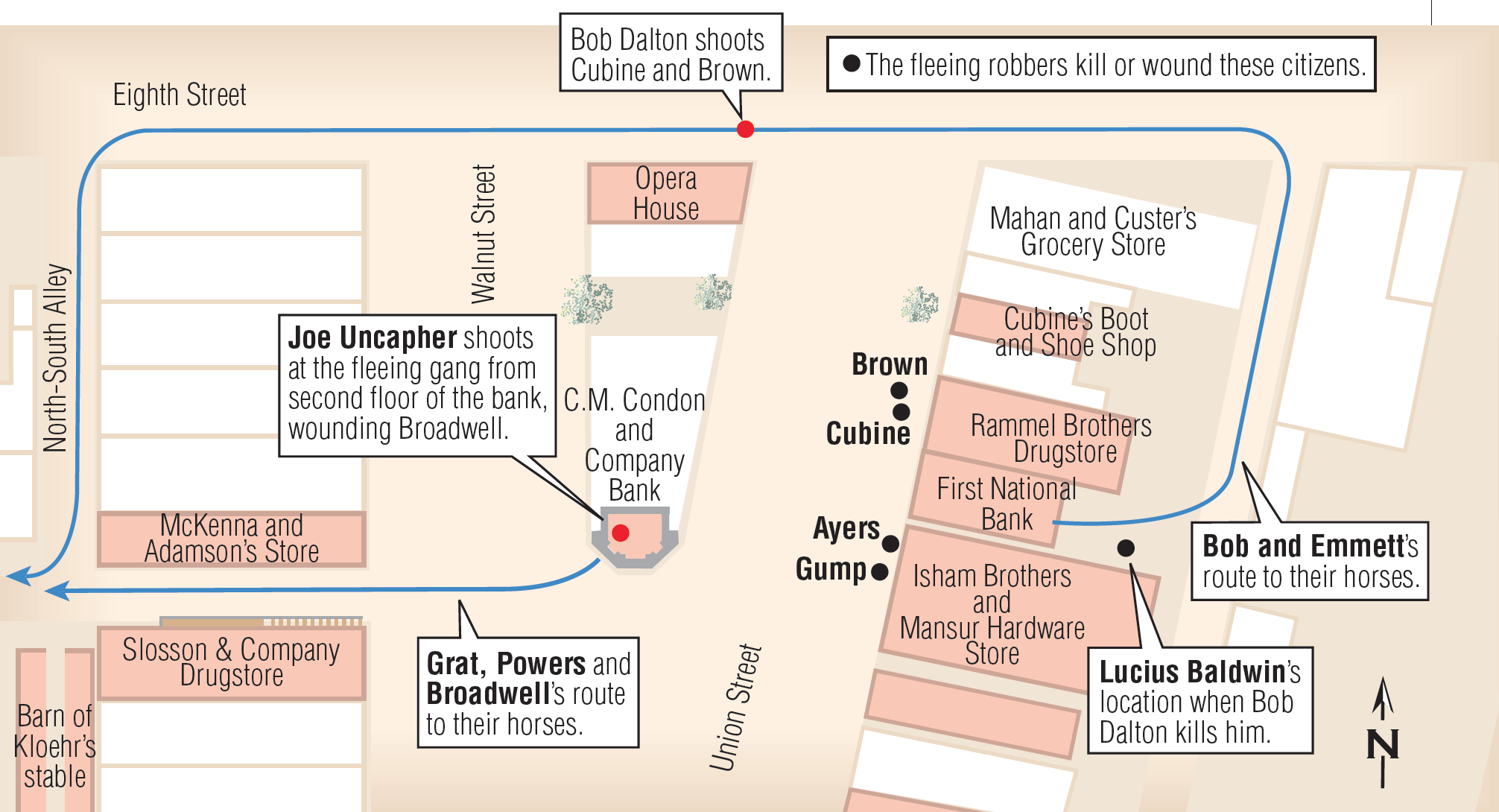

Bob and Emmett finally accumulated some 20,000 dollars in gold and paper money. Thus far, no one had been shot, and all that remained was the dash across the plaza to the horses. Forming up the three bank employees and four customers in front of them, they walked out the front door—and into the sights of the townspeople’s rifles.

Suddenly, the street erupted in gunfire, as dozens of citizens dove for cover. Bob’s prisoners ran into the street, as the two brothers jumped back into the bank. Round after round entered the building, as the defenders fired from doorways, rooftops and any form of cover they could find.

Grat and his men were still dallying in the Condon Bank, as dozens of bullets suddenly pocked the walls and holed the windows. One round caught Dick Broadwell in the arm, rendering his Winchester useless. Shortly thereafter, a hardware store worker placed a round in Bill Powers’s chest.

A citizen later recalled looking in the bank window and seeing the outlaws “running back and forth…and I thought of rats in a trap seeking a way out….” If the outlaws had done proper reconnaissance, they would have known that the bank had a back door, which would have removed them from the immediate line of fire.

At the First National, Bob Dalton did see a back door, and, using the bank teller as a shield, he and Emmett exited the building into a vacant lot. They immediately encountered young Lucius Baldwin, who mistook the outlaws for fellow citizens. After a sharp warning to the confused Baldwin to drop his pistol, Bob shot him down. He was the first townsperson to die that morning.

In the exchange of shots, the outlaws were managing to do a fair amount of damage. Either Powers or Broadwell had shot hardware employee Arthur Reynolds in the foot before being wounded himself, and Bob’s Winchester was taking a fearsome toll. He shot one man through the hand, and fired three rounds into the back of bootmaker and old family friend George Cubine. And when Charles Brown, a 59-year-old shoemaker who worked alongside Cubine, reached to grab his dying friend’s rifle, Dalton shot him dead as well.

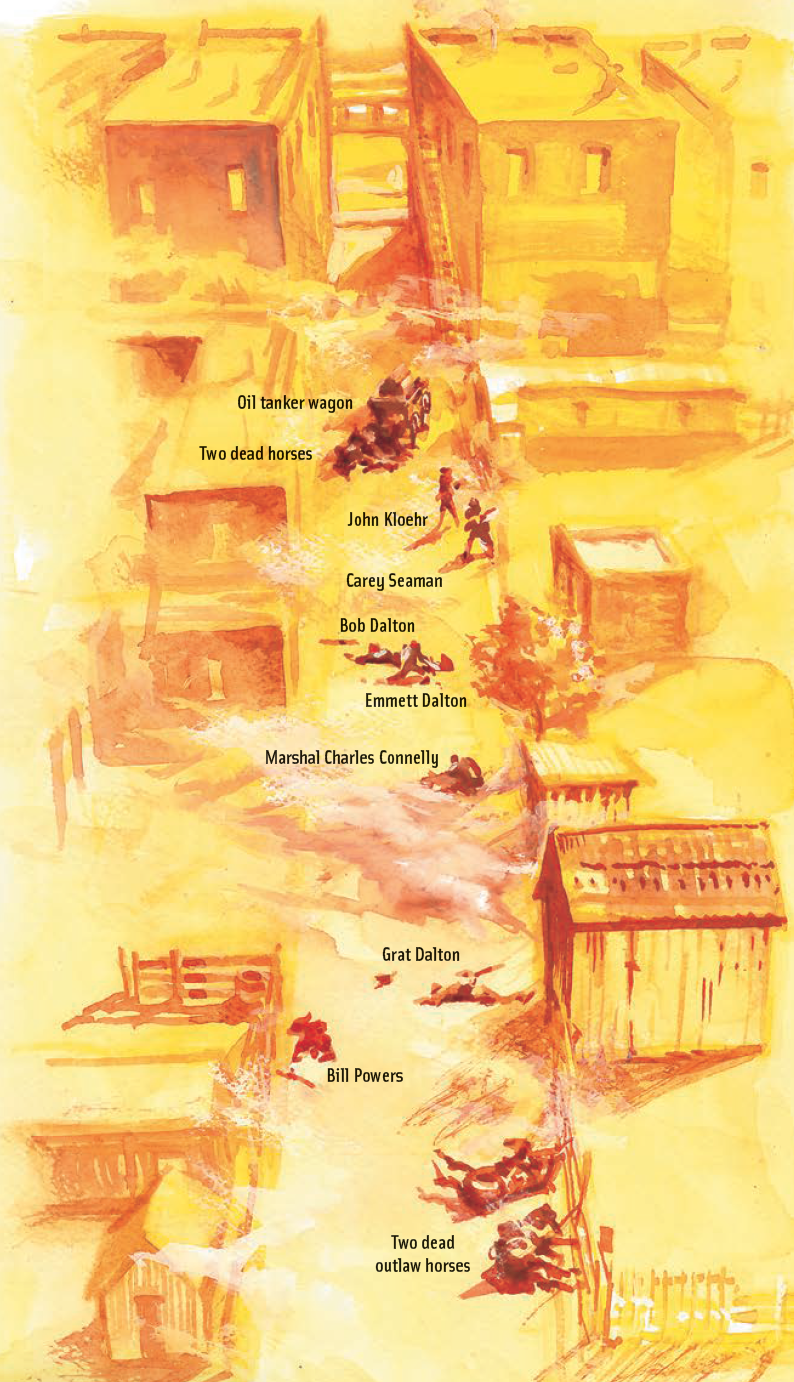

Coffeyville, Kansas: Wednesday Morning, October 5, 1892

PHASE 1

The gang members intend to tie their horses at McCoy’s Hardware store or the Opera House, but they find the street torn up and the hitching posts removed. Instead, they ride south on Maple and enter a narrow alley where they dismount and tie their horses to a fence.

Dumb and Dumber

Bob (left) and Grat are the leaders of the raid, and they make at least two fatal mistakes. Grat, 31, is the oldest, but he proves to be a poor leader. His slow-witted actions in the Condon Bank lead to a major debacle. As to the choice of where to tie the horses (see alley fence, above left), Emmett later admits, “There was no worse place in Coffeyville than the place Bob picked.”

– All photos on this page courtesy Coffeyville Historical Society –

“The last time I ever saw Bob or Grat was just before the Coffeyville raid, when the three boys came to Mother’s home near Kingfisher. They had been running and hiding for months. Their clothes were worn out. I gave them about all the clothes I had, a good Stetson hat, which Bob had on when he was killed, and a good coat and overcoat. They scarcely thanked me. They expected me to keep on putting up for them indefinitely.”

—Littleton Dalton

Death Alley

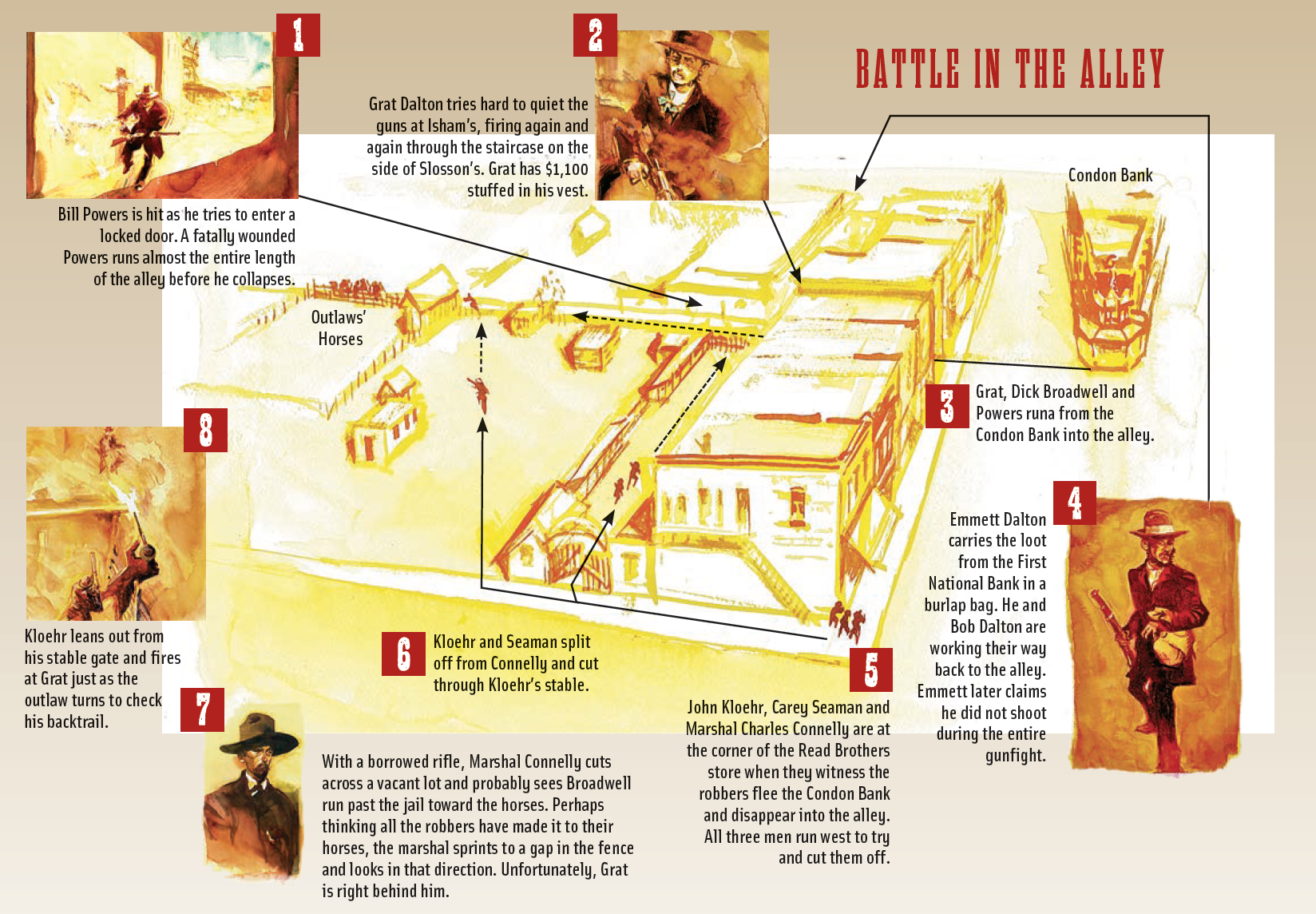

At the Condon Bank, Grat finally decided it was time to make a dash for the horses. He stuffed a wad of paper money inside his vest, and the three outlaws ran out of the bank toward the mouth of the alley, across a plaza that was alive with gunfire. One observer later commented that they ran “with heads down, like facing a strong wind.” Almost at once, Grat and Powers were hit hard—Powers for at least the second time—but the three managed to stagger into the alley.

The roar of the firing was constant and deafening—and combined with the screams of wounded and dying men and horses—the town presented a fair impression of Hell. Bob and Emmett were providing their cohorts with what covering fire they could, and when Bob spotted bank employee Tom Ayers, he shot him through the head. Miraculously, Ayers would survive to tell the story for years to come.

The alley now became the focus of the townspeople’s fire, as the bandits desperately strove to reach their mounts. Powers received yet another round, killing him beside his horse. Broadwell was shot again as well, but managed to keep his feet. Grat, badly wounded but still able to fire his rifle, managed to find what sparse shelter the alley offered. And when Charley Connelly, the town’s much-loved marshal, entered the alley, Grat fatally shot him in the back.

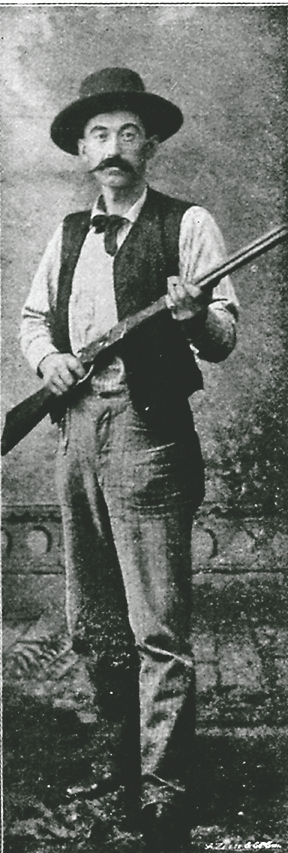

Livery owner John Kloehr, who was acknowledged to be the town’s finest marksman, drew a bead on Grat Dalton and shot him through the throat, breaking his neck and killing him instantly.

Dick Broadwell actually managed to mount his horse, but two townsfolk opened up on him at close range with rifle and shotgun. Somehow, Broadwell stayed in the saddle, clutching the horn as he rode out of the alley, only to fall dead in the road less than a mile outside of town.

Unaware of the fate of their three comrades, Bob and Emmett made for the alley and their horses. Years later, Emmett recalled that his big brother was still confident of leaving Coffeyville alive. “Go slow!” Bob advised. “Go slow, I can whip the whole damn town!”

Immediately upon entering the alley, Bob was hit, and collapsed against a pile of cobblestones, still firing his rifle. Once again, John Kloehr leveled his deadly weapon and shot Bob in the chest, leaving him out of the fight and dying.

Incredibly, up to this point, young Emmett had come through unscathed. Once in the alley, however, he was hit at least twice, one of the shots fracturing his arm. Still carrying the money sack, he mounted one of the two horses left standing amid the withering fire. He was hit several more times, but managed to stay aboard. As he started to ride out of the alley, Emmett saw his dying brother, and he did an extraordinary thing: He turned his horse back into the hail of bullets. As he later wrote, “All thought of money—of my own life or of escape vanished. I only knew that I had to reach Bob.”

Depending on which version one credits, Bob either said, “It’s no use,” or, in Emmett’s more florid recollection, “Goodbye, Emmett. Don’t surrender, die game.” In all likelihood, he said nothing at all. Either way, Emmett’s was a brave but futile gesture, and for a brief moment, no one fired. Then, as he reached for Bob’s hand, a shotgun roared, and Emmett fell in the dust of the alley that had already seen the finish of both his brothers and his two comrades.

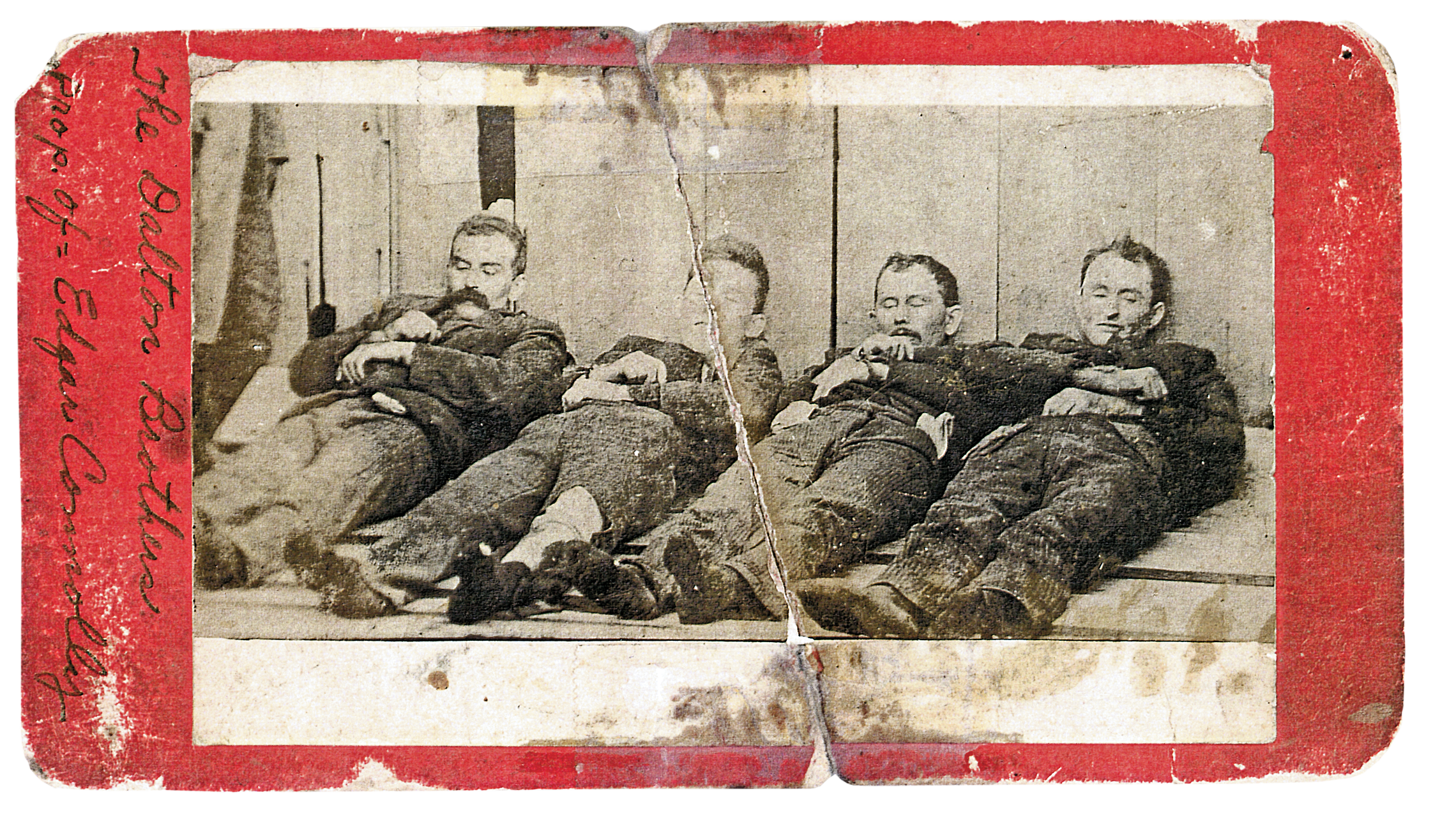

Someone shouted, “They’re all down!” Suddenly, the guns, which had roared steadily since the battle began, were silent, as the townsfolk began to survey the carnage. “Death Alley,” wrote one chronicler, “was a charnel house.”

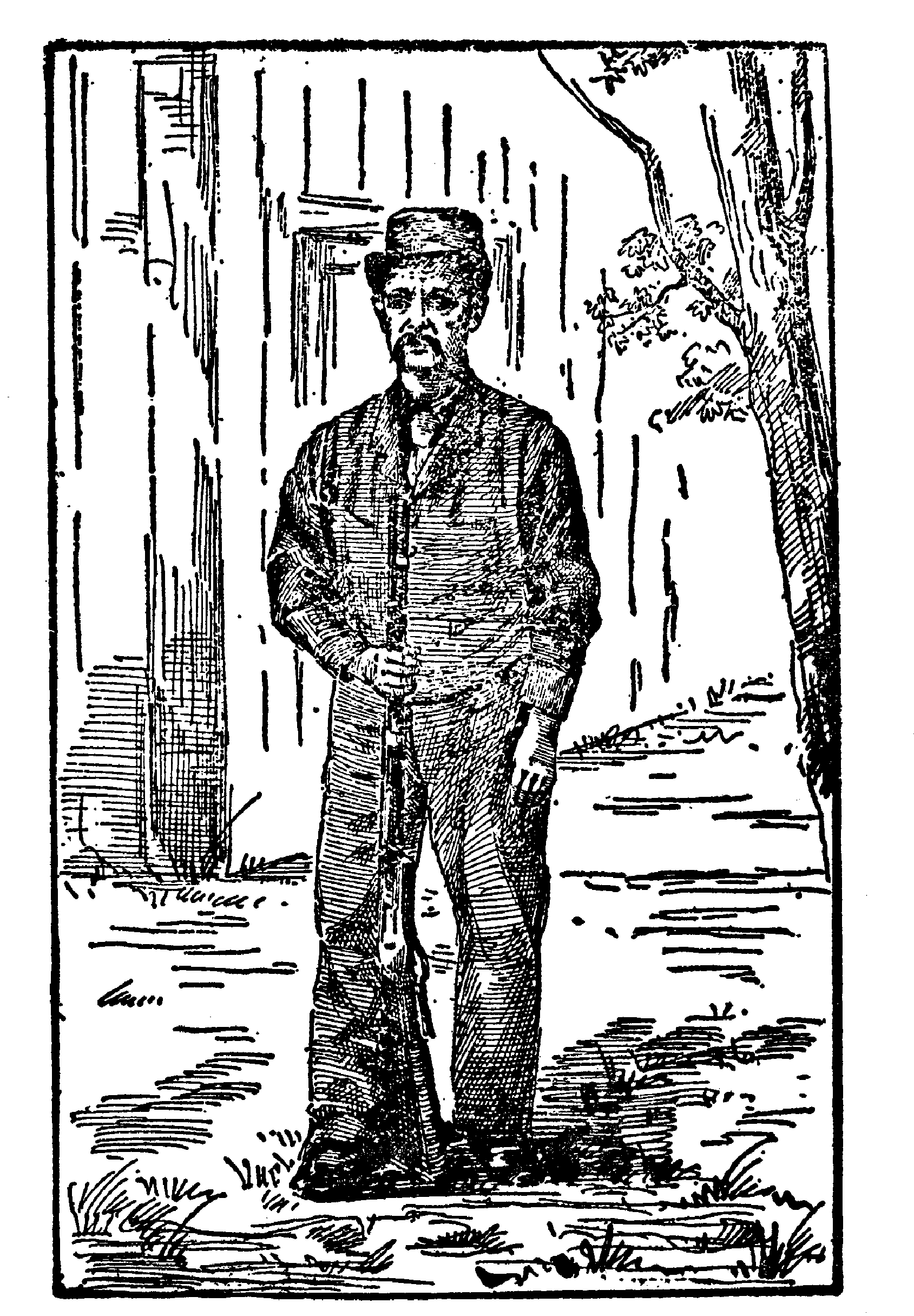

Still conscious, Emmett was taken to the doctor’s office, amid cries calling for his immediate lynching. The doctor assured the citizenry that a rope was unnecessary since the youth was bound to die soon anyway. Beyond all expectation, Emmett—who had sustained no fewer than 25 wounds—survived.

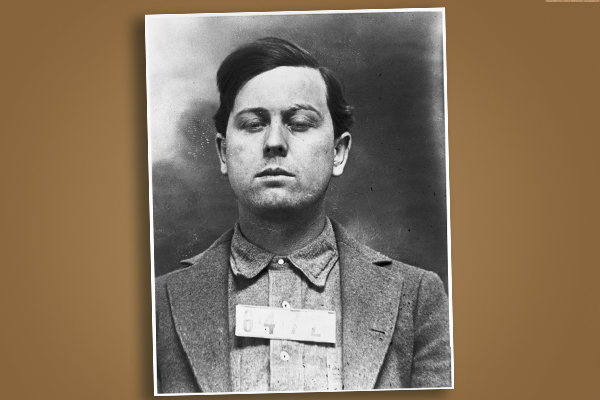

Boards were immediately set up in the alley, and the four dead outlaws were unceremoniously hauled over to them, laid out side by side, and photographed. Souvenir hunters snipped pieces of their bloody clothing, and when the townspeople had had their fill of staring at them, they were buried in plain coffins in the local cemetery. Until the late ‘60s, their only marker was a random lead pipe someone placed ignominiously on their grave. Dick Broadwell’s family soon claimed his body, but the other three lie there still.

Shortly after their interment, the long-suffering Adeline came to town, along with two of her other sons, to pay her last respects to her wayward children. Wrote one historian, “Adeline was courteous and quiet, and apparently was treated politely and sympathetically by the people of Coffeyville.”

One of the sons who accompanied Adeline to Coffeyville was Bill Dalton, who railed at the town over the deaths of his brothers. The boys were wrong in their purpose, he acknowledged, but “they were right when they shot the men who were trying to kill them!” Bill later formed his own outlaw gang with Oklahoma badman Bill Doolin and himself fell to lawmen’s guns less than two years later. Bill’s grave is unmarked in his wife’s family plot in Turlock, California.

PHASE 2

After the shooting starts, the gang’s plan begins to go south. Here’s what happens:

PHASE 3

Although the outlaws are a little over 100 yards from their horses and freedom, it may as well be 100 miles because Isham’s front doors face straight into the alley. For the citizens at the hardware store, it’s like shooting fish in a barrel.

Eyewitnesses agree that “volley after volley chased the fugitives.”

“Go slow!” Bob shouts to his brother, Emmett. “I can take the whole town.” As the duo reaches the alley, Bob scans the high windows looking for shooters. A bullet from Kloehr’s stable (or Isham’s hardware store) nails him in the chest.

Blaze of Glory

The citizens of Coffeyville had displayed considerable heroism on the day the Dalton Gang targeted their town. For his part in subduing the outlaws, John Kloehr was presented with a factory-engraved rifle, a gesture of the Winchester factory. A humble man, Kloehr for the rest of his life refused to discuss the fight or his part in it. A number of others, equally brave, went unheralded.

With hundreds of rounds fired, the entire fight had lasted no more than 10 or 12 minutes—but the butcher’s bill was terrible. In addition to the four slain outlaws, as a result of the chaos the Daltons had levied on the town, four of Coffeyville’s leading citizens lay dead, and several others were injured.

While still recovering from his many wounds, Emmett Dalton was sentenced to a term of life imprisonment in the Kansas State Penitentiary. However, after spending 15 years behind bars, a rehabilitated Emmett received an unconditional pardon. He lived into his late sixties, during which time he produced two historically skewed volumes on the Dalton Gang (one of which inspired the first of several Dalton-themed movies), and became something of a Hollywood celebrity. He also ordered a headstone to be placed over the graves of his brothers and Bill Powers.

While most Western history buffs would likely be hard-pressed to name even one of the four citizens who died protecting their town on that bright October morning, the sanitized myth of the Daltons continues to flourish. Two photographs of the four dead outlaws recently sold at a Western collectibles auction for over $6,000. And less than a decade ago, one of Bob Dalton’s pair of fancy engraved Colts hammered down at $322,000. Ultimately, for the Daltons, crime did not pay; however, the wake they left continues to generate considerable public interest, as well as revenues far beyond what the gang ever dreamed of acquiring through larceny. Americans indeed love their outlaws.

The Terrible Tally

4 Outlaws killed

4 Citizens killed

4 Horses killed

4 Wounded

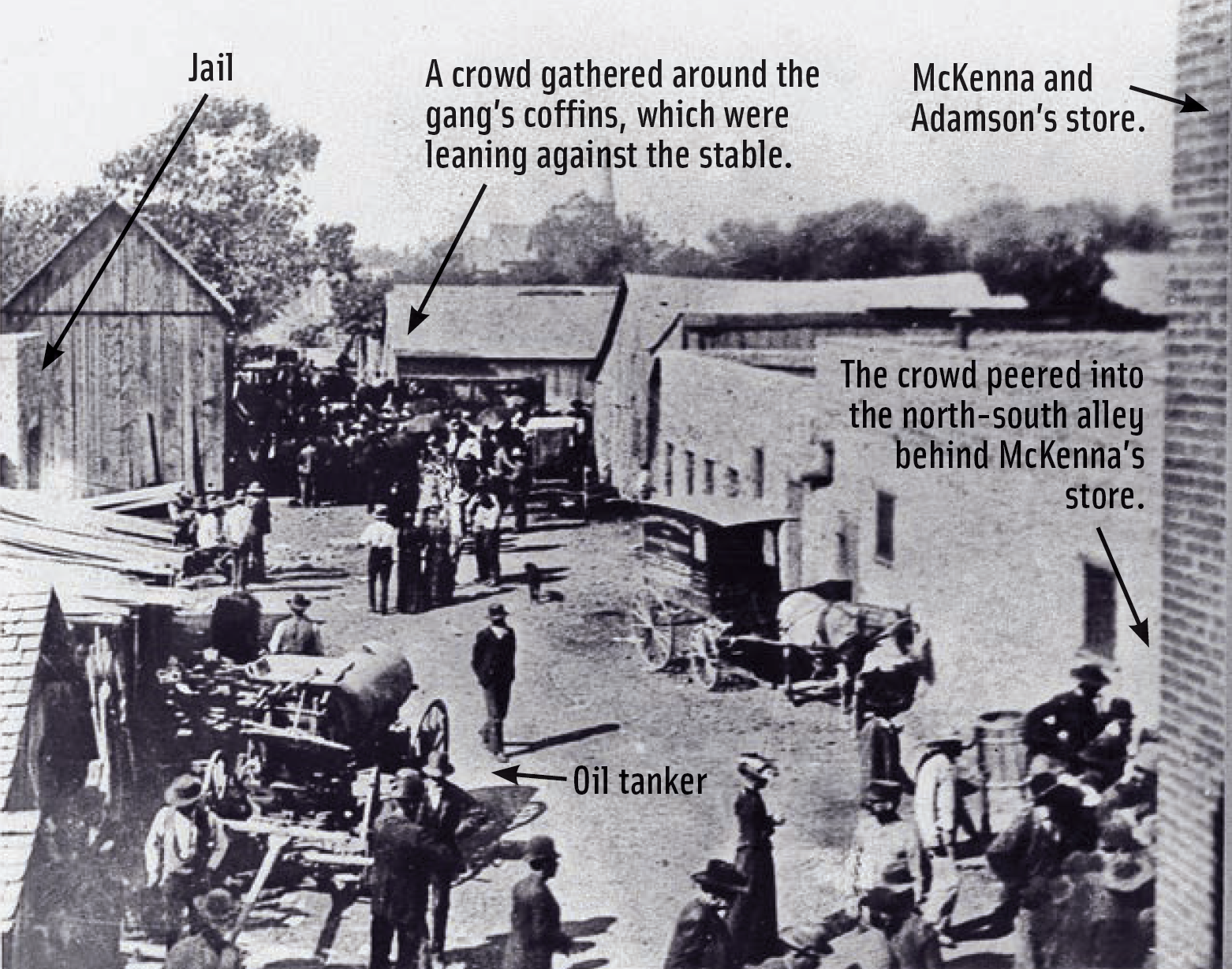

Death Alley Aftermath

“They’re all down,” comes the cry as crowds of people come out of doorways and from blocks away. Describing the scene, a reporter writes, “dead and dying horses and smoking Winchesters on the ground add to the horrors of the scene. . . . Excited men, weeping women and screaming children thronged the square.”

Death Alley After the Raid

Hometown Heroes

•Bavarian John J. Kloehr (pronounced “Clair”) was taking a nap in his stable when the shooting started. Kloehr (above), 34, was one of the best shots in town and often traveled to out-of-town shooting tournaments. Married, with four children, Kloehr was modest and did not like to talk about himself. He was often credited for killing Grat and Bob Dalton, and Dick Broadwell, but Kloehr told a Wells Fargo agent he killed only Grat. The agent noted, “[Kloehr] said that he sighted for his head, but undershot a little for he hit him in the neck right on his Adam’s apple and broke his neck.”

•A barber by trade, Carey Seaman (below) worked at Smith’s barber shop next door to Isham’s. He stepped into a battlefield when he returned to work after hunting. Seaman retrieved his shotgun from his wagon, fired both barrels into Emmett Dalton and ended the fight.

Adeline’s Boys

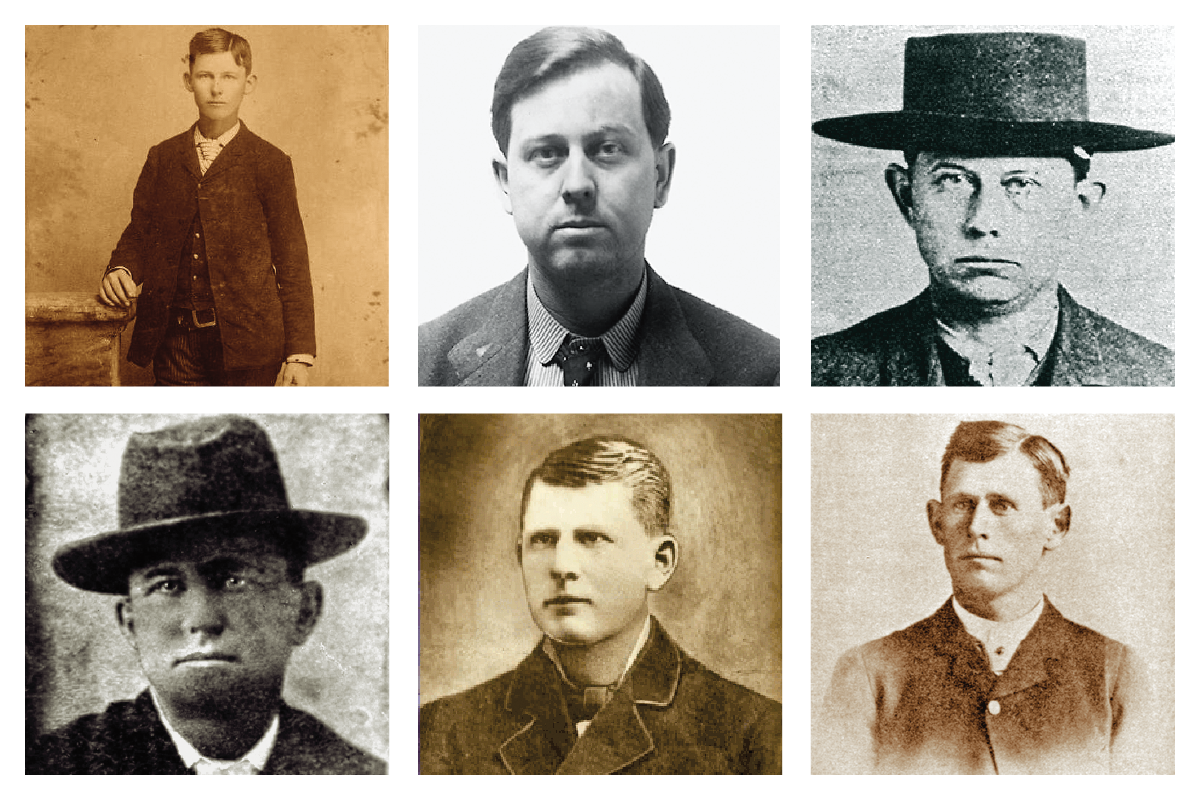

Adeline and Lewis Dalton had 15 children, 10 boys and five girls. Of the 12 who lived to adulthood, one of the boys, Frank (bottom middle), died as a lawman, while four of his brothers he had deputized from time to time, turned to outlawry. The outlaws are (from top left) Bob, Emmett, Grat and Bill Dalton. Littleton, lower right corner and his brothers (not pictured) Ben, Cole and Sam lived straight and narrow lives.

Ron Soodalter is an award-winning author, with three books and over 400 articles in print. He currently serves as chairman of the board of the Abraham Lincoln Institute. Ron currently lives in Cold Spring, New York.