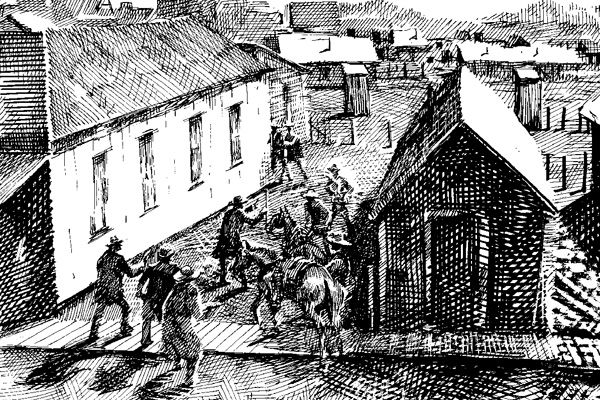

October 26, 1881

October 26, 1881

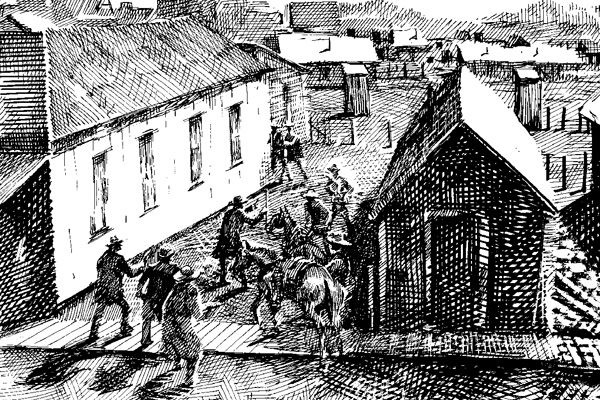

Doc Holliday remains out on Fremont Street as Virgil and Wyatt Earp enter the lot between Fly’s boarding house and the Harwood House.

Holding Holliday’s cane in his right hand, Virgil Earp surveys the scene. Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury wear six-shooters at their sides. Seeing Tom McLaury resting a hand on a rifle housed in a scabbard on Billy Clanton’s horse, Doc Holliday steps up, throws back his overcoat and levels his shotgun. The city marshal speaks. “Throw up your hands boys, I intend to disarm you!”

Frank McLaury replies, “We will.” But, instead of reaching for the sky, he grabs his pistol, causing Wyatt Earp to draw his own revolver from his overcoat pocket. Blind to Frank McLaury’s move and believing his party to be under attack, Billy Clanton reacts by jerking his shooter, cross-draw style.

With two Cow-boys clearing leather, a frantic Virgil Earp flings both arms up and bellows, “Hold on, I don’t want that!” Two shots explode nearly as one. Wyatt’s shot busts into Frank McLaury’s gut; Billy’s shot goes wide of the mark, passing between Wyatt and Morgan Earp. Virgil Earp switches Holliday’s cane to his left hand and retrieves the pistol from his waistband. As his weapon appears, Frank fires his first shot, hitting the City Marshal Virgil Earp in the right calf and dropping him. Stunned by the sudden shooting, Ike Clanton springs at Wyatt Earp, grabbing Earp’s pistol hand and wrapping his right arm around Wyatt’s shoulder.

Morgan fires, hitting Billy and collapsing his lung.

Virgil is back up on his feet now, firing his first shot at Frank, the man who had wounded him. Under fire, Frank staggers toward Fremont Street.

At long last Wyatt pushes Ike off, saying, “The fight has commenced. Go to fighting or get away.”

Morgan Earp screams, “I’ve got it, Wyatt!” and keels over. A bullet has gouged through one of Morg’s shoulder blades. Taking advantage of the distraction, Ike scoots behind Wyatt and clambers through Fly’s front door.

Through all this, Doc Holliday has been waiting, trying to get a clear bead on Tom McLaury. Billy Clanton’s horse has bolted forward at the first shot and blocked a clean shot. Reading the situation and believing it is Tom who has wounded Morg, Wyatt fires a shot, hitting Billy’s horse and making it break away. As McLaury reaches out toward the animal, Doc pumps 12 buckshot under the right armpit of the Cow-boy. McLaury spins around and bounds away toward the corner of Third Street, where he crumples down in a heap. Thinking he has missed a sure shot, Holliday throws the scattergun down in disgust, yanks his nickel-plated pistol and fires two quick rounds at Billy Clanton, who is leaning against the corner of the small building just west of Fly’s.

By now, Morgan Earp is back up and is also shooting at Billy. Inside the lot, Virgil and Wyatt join in, making young Clanton their primary target. Out on Fremont Street, Frank McLaury is still holding the lines of his horse. The effects of Wyatt’s shot are readily apparent.

Hit in his right arm, Billy switches his shooter to his left hand and continues to shoot. Hit again, Billy squats down on the ground, bracing his revolver across his knee and firing again and again. As Wyatt edges out of the lot onto the street, he hears what he takes to be a gunshot coming from behind him and yells, “Look out Morg, you’re getting it in the back!” Twisting quickly, Morgan Earp trips and falls over a mound of earth covering a recently installed water pipe. Carefully, and unnoticed, Doc has circled around the wobbly Frank, covering nearly 50 feet. Having started the fight near the northwest corner of the lot, Doc is now way out in the middle of the roadway.

“I’ve got you now,” McLaury challenges.

“Blaze away! You’re a daisy if you have,” counters Holliday (Daily Nugget, Oct 27, 1881).

Frank McLaury’s gun flashes. Its bullet hits Doc’s pistol pocket and skins across his hindquarters. As McLaury fires, both Holliday and Morgan Earp, now sitting up out in the street, also squeeze their triggers. Morg’s bullet catches the Cow-boy under the right ear, pulverizes his brain stem and slams Frank’s body sideways, heel over head.

At the northwest corner of the lot, Billy Clanton vainly seeks to continue the fight. Photographer C.S. Fly springs from his house brandishing a Henry rifle. As Billy pleads for more cartridges, Fly snatches the six-shooter from the dying boy’s grip. The fight is over.

Step by Step

To the world at large, Doc Holliday was one whiskey-soaked, bullet-spitting, Son O’ Thunder whose only saving grace was that he would soon be dead. His menacing public persona lent credence to claims that he was primarily responsible for the so-called “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.”

Sporting an unsavory frontier-wide reputation as a deadly killer, it was Doc Holliday who raged against Ike Clanton the night before the O.K. Corral shoot-out. It was Doc Holliday who was the primary target for Ike Clanton’s anxious hunt throughout Tombstone on the morning of Oct. 26, 1881. It was Doc Holliday who, witness after witness (for the prosecution, that is) identified as having fired the first unprovoked shots at peaceful, non-resisting ranchers. So it is that Doc Holliday’s role in the West’s most famous gunfight is central to any understanding of what really transpired that bloody afternoon. But what does the evidence really tell us? That large question can best be addressed by breaking it down into smaller, more specific inquiries.

• Did Doc’s “death wish” exacerbate the fight?

The popular image of Doc Holliday as a man racing toward death with little regard for those he takes with him isn’t borne out by his conduct at the O.K. Corral gunfight. Instead, his actions seem measured if not restrained. Positioned out on Fremont Street, as back-up to the brothers Earp, he fully met the responsibilities of that assignment. Instead of initiating an unprovoked and unmotivated onslaught, he patiently covered the flank of the city marshal.

If Tom McLaury was unarmed, Doc could not have known it. As McLaury reached out toward the fleeing animal, Doc Holliday couldn’t tell if Tom’s intent was to maintain the horse as a shield, or to access the rifle housed on the terrified mount. Doc instinctively fired 12 buckshot into the Cow-boy’s right side. One thing is certain: McLaury’s fatal wound, located under the right armpit could never have been received had he actually been facing the city marshal and holding open the lapels of his vest or coat as Ike Clanton testified. Tom McLaury was actively reaching out in front of his person and facing Fremont Street when hit. His wound’s position confirms Wyatt Earp’s account of Tom’s shooting far better than does Ike Clanton’s.

After the shooting of Tom McLaury, and before the final stand-off with Frank McLaury, the only shots attributed to Doc Holliday were two rounds directed at Billy Clanton. The witness, C.H. Light, who saw the shooting from the Aztec House on the northwest corner of Third and Fremont, gave detailed testimony of those shots. Clearly then, Doc didn’t become locked in on Billy. He remained alert enough to what was going on around him to take notice of the still dangerous Frank McLaury.

Finally, Doc’s careful stalking of Frank McLaury showed remarkable patience. Doc Holliday had to have walked nearly 50 feet from his original position at the start of the gunfight, to his final location at the shooting’s end. This wasn’t the action of an out-of-control “bullet-spitting” terror. This was the considered and deliberate approach of a cautious warrior. No doubt about it: Doc Holliday could be a royal demon when on a rampage. However, on October 26, 1881, near the O.K. Corral, when called on to support the city marshal, he was the right man in the right place.

• Did Doc Holliday return to Tombstone to hunt-up Ike Clanton?

Big Nose Kate Elder recalled that she and Holliday were in Tucson on October 25, 1881. “Doc was bucking at faro, I was standing behind him, when Morgan Earp came and tapped Doc on the shoulder and said, ‘Doc, we want you in Tombstone tomorrow. Better come up this evening.’” Elder said she accompanied Holliday and Morgan back to the mining camp. “Doc left me at his room and went with Morgan at 10:30 p.m. when we got back.” Two and one-half hours later, Doc Holliday, backed by Morgan Earp, allegedly commenced to verbally abuse Ike Clanton.

Kate’s account of returning from Tucson on the evening of Oct. 25 is undermined by the Tombstone Daily Nugget of that date, which reported, “Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday returned from Tucson Saturday evening [Oct. 22].” This is important because the urgent call for Holliday’s presence has been interpreted as indicating the Earps were readying themselves for an imminent fight. That Doc returned to Tombstone three days before Ike even hit town, weakens the scenario that he hurried back to provoke a fight with Clanton.

• Did Doc Holliday try to provoke Ike Clanton into a gunfight on October 25, 1881?

Ike Clanton claimed that “the night before the shooting” Doc Holliday found him at the Occidental Lunch Room and began to abuse him: “He had his hand on his pistol and called me a damned son-of-a-bitch and told me to get my gun out. I told him I did not have any gun. I looked around and I seen Morg Earp sitting at the bar behind me, with his hand on his gun. Doc Holliday kept abusing me.”

No one denied hot words were exchanged between Holliday and Clanton. Wyatt Earp said that Doc and Ike were still arguing outside when he, himself, finally emerged onto the street. According to the Epitaph version of Earp’s testimony, Wyatt claimed, “I then went to Holliday, who was pretty tight, and took him away.” While Earp said the incident happened at the Alhambra Saloon, Clanton testified before the coroner’s jury that it occurred at the Occidental Lunch Room. Later, at Spicer’s hearing, Ike had the exchange starting at an unidentified lunch stand “near the Eagle Brewery Saloon.”

Clanton’s claim that Doc Holliday instigated the confrontation was never seriously challenged in court. Because of that, Ike’s account is often accepted at face value. Wyatt’s version implies that Holliday was drunk and provocative. However, there are problems with Clanton’s tale. Ike’s odd lack of precision in identifying where his run-in with Doc happened begs the question of Clanton’s own wherewithal when he and Doc tangled. Had Ike, himself, been drinking? Did Clanton purposely elect to have lunch in an acknowledged Holliday haunt? If so, who was doing the hunting that night?

Wyatt Earp’s testimony provides an important clue to what may have happened. He testified that following the attempt to rob the Benson stage in March, 1881, in which the driver and a passenger were killed, frustration over his inability to apprehend the suspects — Bill Leonard, Harry Head and Jim Crane — led him to enlist Ike Clanton’s help by offering him the Wells Fargo reward for their capture. The deal fell through when the three suspects were killed, but it left a nasty secret. Eventually, Ike learned that Marshal Williams, the Wells Fargo agent in Tombstone, had figured the deal out, and he suspected that Doc Holliday knew as well. In the 10 days before the street fight, Ike questioned Wyatt about what Doc knew. Wyatt told him Doc knew nothing, but suggested Ike ask Doc when the gambler returned to Tombstone.

By the time Doc reached Tombstone on October 22, Ike had left town. Clanton came back to Tombstone on October 25, and he may have gone searching out Holliday, not necessarily to fight, but to ease his gnawing apprehension over being found out. Holliday may have approached him simply to tell Ike he didn’t know anything about Ike’s deal with Wyatt. Either scenario could have escalated into a quarrel.

So, while it is certain that Doc Holliday and Ike Clanton locked horns, the why and wherefore are not obvious. Ike’s account presents Holliday’s behavior as arbitrary rather than clearly motivated, but Wyatt provides a plausible motive for the exchange. Clanton never convincingly spelled out the reasons for Doc’s alleged verbal assault. That alone suggests more transpired than Ike ever let on. After all, he had a lot to hide.

• When the Earps and Holliday passed Bauer’s Market, did Morgan tell Doc to “Let them have it?”

Martha J. King said that while she was in the butcher shop (Bauer’s Market), and as the city marshal’s party passed, she heard one of the Earps say, “Let them have it!” and to that Doc replied “All right.” However, Mrs. King didn’t know one Earp from another and couldn’t specifically identify the initial speaker.

Mrs. King’s testimony, as it appeared in The Nugget, November 6, 1881, is as follows: “These four men were on the sidewalk walking leisurely along . . . Mr. Holliday and the man on the outside were just a little in front of the middle two; they were walking nearly abreast of each other; Holliday was on the left hand side, next to the building; I heard remarks from the party as they passed; I heard the gentleman on the outside . . . as he looked around say to Mr. Holliday. ‘Let them have it;’ Mr. Holliday said, ‘All right.’ I suppose he said it to Mr. Holliday, for he answered him; no names were used; I heard no other conversation, at this exact time. . . .”

Thus, Mrs. King refutes the popular belief that the Earp party was walking two by two. All four were “walking nearly abreast.” Since the far outside man, closest to the street, spoke to the far inside man (Holliday), who was closest to the building, it is wholly improbable that the two middle men could not have heard the exchange. What exactly was meant by the “Let them have it!” statement? That isn’t clear because Mrs. King never heard it in any context. Was one of the Earps telling Doc to just blast away? Perhaps, but improbable. As these words were allegedly being spoken, Sheriff Johnny Behan was standing directly in front of the Earp party. Several witnesses testified that the sheriff tried to stop the city marshal’s party right at the butcher shop. In light of this, Virgil Earp could well have been telling Holliday to hand the scattergun over if the sheriff demanded it. The sound of “Let him have it!” when spoken rapidly, is virtually identical to the sound of “Let them have it!”

• Did Doc Holliday fire the opening shot in the street fight?

The Cow-boys steadfastly claimed that Doc Holliday and Morgan Earp opened fire on the Clanton/McLaury group without any provocation whatsoever. Ike Clanton said that when the Earps and Doc Holliday reached the Cow-boys, “They pulled their pistols as soon as they got there. . . .” and Virgil Earp ordered the Cow-boys to “Throw up your hands!” According to Ike Clanton, with this, someone, possibly Wyatt, yelled out, “You sons-of-bitches have been looking for a fight and now you can have it!” and Billy Clanton replied, “Don’t shoot me. I don’t want to fight!” Then, “Tom McLaury threw open his coat saying, ‘I haven’t got anything, boys, I am disarmed (testimony of William Claibourne).’” Ike claimed both he and Frank McLaury held up their hands in complete and immediate submission in response to the marshal’s order.

At this moment, Sheriff Behan became preoccupied with a nickel-plated pistol held, he believed, by Doc Holliday. He later recalled, “My attention was directed to the nickel-plated pistol for a couple of seconds. The nickel-plated pistol was the first to fire.” Another observer, Billy Allen, was standing out on Fremont Street. He supported the sheriff’s pronouncement. “I think it was Doc Holliday who fired first. Their backs were to me. I was behind them. The smoke came from him.”

Standing in the vacant lot as the shooting erupted, William Claiborne contended, “The shooting commenced, right then, in an instant, by Doc Holliday and Morgan Earp — the two shots were fired so close together it was hard to distinguish them.” When the shooting started, Wes Fuller was deeper in the lot than Claiborne. He agreed that “Morg Earp and Doc Holliday fired the first two shots.” Finally, Ike Clanton himself unequivocally declared, “The first shots were fired by Holliday and Morgan Earp.”

• Given the consistency of the witnesses claiming Doc started the gunfight, why didn’t their claims prevail?

First, Sheriff Behan’s obsession with Holliday’s nickel-plated pistol undermined his inability to account for Doc’s use of a shotgun. Clearly, Virgil handed Holliday the shotgun before the Earps left Fourth and Allen. Martha King testified she saw Doc carrying it. Had Behan focused on a shotgun as it was aimed and fired, his testimony would have been much more compelling. As it is, the Cow-boy account of the fight requires us to believe that Holliday carried the shotgun but, instead of initially using it, for some mysterious reason Doc pulled his pistol, fired it, returned it to his pocket, fired the scattergun, and then once again retrieved his pistol to finish off the fight.

This cumbersome scenario is too convoluted to be convincing. And its oddness only increases if Billy Allen’s testimony is accepted at face value. Allen was the only prosecution eyewitness at Wells Spicer’s hearing to distinctly acknowledge the firing of a shotgun in the opening salvo. Remember, Allen said that the smoke from the first shot came from Holliday. He added, “I could not tell who fired the second shot, they came in such quick succession. I think the first was a pistol shot and the next a double-barrel shotgun:” But if Holliday had the shotgun, he would have fired the second shot.

Next, while the four prosecution witnesses all agreed that Doc fired one of the opening shots, they contradicted each other on who Holliday actually shot at. Behan said, “the nickel-plated pistol was pointed at one of the party. I think at Billy Clanton.” Yet, Claiborne claimed, “Doc Holliday shot at Tom McLaury and Morgan Earp shot at Billy Clanton.” Finally, Ike asserted, “Morgan Earp shot William Clanton, and I don’t know which one of the McLaury boys Holliday shot at. He shot at one of them.”

The problem with Ike’s story is that he also testified that he was standing at the northwest corner of Fly’s building with Wyatt Earp directly in front of him. Clanton claimed that immediately upon Wyatt’s arrival, “He shoved his pistol up against my belly and told me to throw up my hands.” So, with Doc Holliday, Billy Clanton and both McLaury brothers all admittedly to his rear, and with Wyatt Earp actively pressing a six-shooter into his ribs, Ike Clanton would have us believe he clearly saw what was transpiring behind him. Because of this, Clanton’s testimony begins to lose credibility.

Finally the failure of the Cow-boys to offer any clear motive for the alleged unprovoked shooting also hurt their case. Under cross examination, Ike Clanton made a series of preposterous assertions. First, he claimed the Earps and Doc Holliday had “piped off” money from the Benson stage before it had even left Tombstone. This was the stagecoach which was attacked on the night of March 15, 1881, when the driver and a passenger were killed. The problem with Clanton’s tale was that no money was taken in the attempted hold-up. So, the “piping-off” story is an amazingly transparent pipe dream.

Next, Ike Clanton said that Wyatt was so worried about hold-up men Leonard, Head and Crane, implicating the Earps and Holliday in the failed robbery, should they ever be apprehended, that he offered Ike the reward money if he would set up the trio for the Earps to kill. But why would Earp need Ike’s help to find members of Wyatt’s own supposed gang? That puzzle illustrates the increasingly bizarre quality of Ike Clanton’s contentions.

Ike also claimed that, while trying to enlist Clanton’s services, Wyatt freely admitted his part in the aborted stage heist. Then, seemingly out of the blue, Doc Holliday confided to Ike that it was he (Holliday) who had killed the stage driver. Then, on yet another occasion, Morgan Earp advised Clanton about the previous “piping off” of money from that particular stagecoach. Finally, Virgil Earp conveniently admitted how he had thrown the posse pursuing the would-be robbers off the real trail.

All in all, according to Ike Clanton, the Earps and Doc Holliday were so terrified of being found out that they inanely confided to him all the nefarious secrets which allegedly had motivated them to want Leonard, Head and Crane silenced in the first place. Thus, it was the very same fear of being found out which finally compelled the Earps to attempt Ike’s murder at the streetfight. Why Ike was allowed to survive seemed to elude Clanton’s consideration. When Ike Clanton spewed this twisted tale of cockeyed intrigue, he lost his credibility and the case against the Earps and Doc Holliday collapsed.

• What type of shotgun did Doc carry?

The make and gauge of the shotgun Virgil Earp retrieved from the Wells Fargo office and subsequently handed to Holliday were never specified. All we have is the Nugget’s description of Doc “using a short shotgun, such as is carried by Wells, Fargo & Co.’s messengers.” Generally, such weapons were 10-gauge. However, the small number of buckshot in Tom McLaury’s body (12), leads some to speculate it may have been a 12-gauge.

• What kind of pistol did Doc carry into the street fight?

Witnesses gave conflicting descriptions of Doc’s handgun. Sheriff Johnny Behan testified that Doc carried a nickel-plated revolver, while saloonkeeper Bob Hatch and Addie Bourland said they saw Holliday with a dark brown (or bronze) pistol. Despite this contradiction, there is little doubt that Doc’s pistol was indeed nickel-plated. The defense never contested Behan’s claim. In fact, when cross-examining Sheriff Behan, defense lawyers conceded Doc used such a weapon when they asked Behan, “Is it not a fact that the first shot fired by Holliday was from a shotgun; that he then threw the shotgun down and drew the nickel-plated pistol from his person and then discharged the nickel-plated pistol?” This question makes no sense if Holliday didn’t, in fact, carry a nickel-plated pistol into the gunfight.

Yet, when Bob Hatch was asked about Doc’s pistol, he replied, “It looked to me like a brown pistol; I did not see him with a nickel-plated pistol during the fight; whether he had one or not I could not say (Nugget, Nov. 18, 1881).” Then, when Bourland took the stand, she was asked:

“Did you notice the character of the weapon Doc Holliday had in his hand?”

“It was a very large pistol.”

“Did you notice the color of the pistol?”

“It was dark bronze.”

What can be made of this testimony in light of the defense concession that Doc carried a nickel-plated pistol? The most probable explanation for Bourland’s claim is that she mistook the short-barreled shotgun Doc carried at the beginning of the shooting as a “very large pistol.” Positioned clear across the street from the vacant lot, she was more than 75 feet away. From that distance, it would be relatively easy to mistake a short-barreled shotgun, it’s stock concealed by the forearm of the man carrying it, as a “very large pistol.”

Hatch’s testimony is more difficult to deal with. By 1881, non-plated handguns had, for years, been blued rather than browned. That is, the surface color of a non-plated pistol would have appeared dark blue, not “brown.” A nickel-plated revolver, on the other hand, would have a bright reflective quality. It is difficult to see how such a weapon could ever take on a “brown” appearance. Since shotgun barrels were still being “browned,” Hatch’s memory may simply have played a trick on him, transposing the color of the scattergun’s barrel onto his mental image of Holliday’s handgun. Another possibility would be that Doc carried two pistols into the streetfight, one nickel-plated, the other browned. However, no evidence or testimony has ever surfaced supporting this possibility.

• Did Holliday wear a standard gunbelt with a holster?

As reported in the Nugget, “This shot of McLowry’s [sic] passed through Holliday’s pistol pocket, just grazing the skin.” This distinction is important. A “pistol pocket” was a special pocket lined with either canvas or leather to support a pistol in one’s clothing, not a standard scabbard which hung from a belt. Before the shoot-out, witness Wes Fuller observed the Earp party on the corner of Fourth and Allen. He “saw Holliday put one (six-shooter) in his coat pocket.” So, it would seem Doc carried his pistol in his ulster. It remains unclear, however, if the “pistol pocket” hit by McLaury’s final shot was in Holliday’s overcoat pocket, or another such pistol support sewn into Doc’s trousers or undercoat.