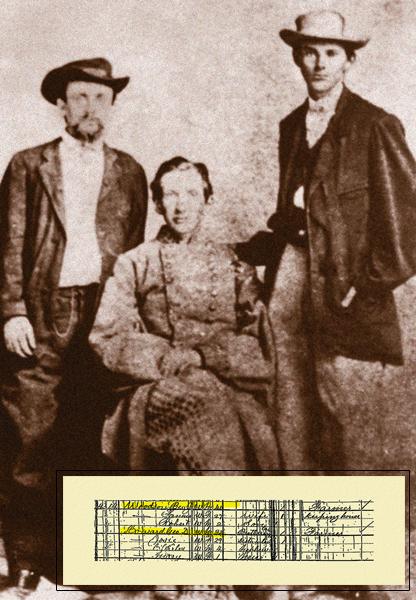

Early in June 1880, census enumerator Charles M. Cantrell came to dwelling number 14 on his list in Davidson County, Tennessee.

Cantrell wrote down the names of 40-year-old Ben J. Woodson; his wife Fannie W. aged 27; and their two-year-old son Robert. Next, he wrote down Geo. D. Howard, noting that he was Woodson’s brother, and then crowding in the words “in-law.” The rest of the household consisted of Josie, Howard’s wife and their children Charles, four, and Mary, one. Mr. Howard and his family soon moved to St. Joseph, Missouri. Not quite two years after Cantrell came to Howard’s house for the census, Howard was shot to death in his St. Joseph, Missouri, home by one Robert Ford. Indeed, “Ben J. Woodson” and “Geo. D. Howard” were none other than two famous outlaws living incognito, Frank and Jesse James.

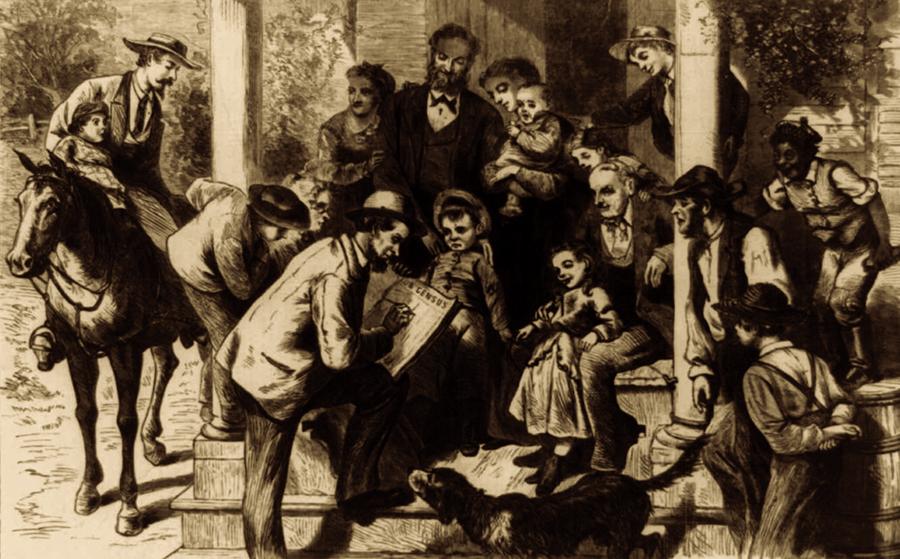

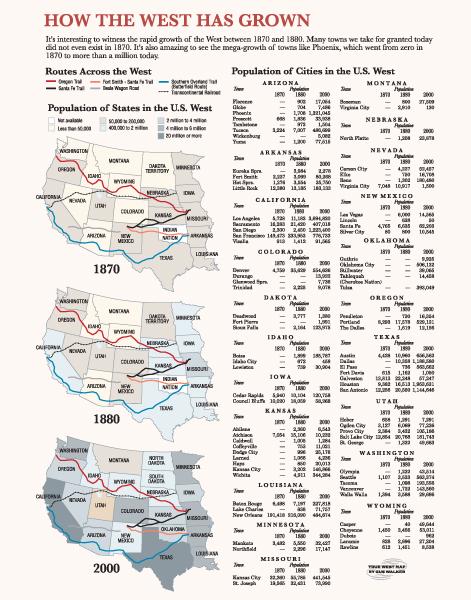

Cantrell’s encounter with the Jameses is only one of the countless glimpses of the Old West to be found in the pages of the United States Census. Every 10 years, a census of the entire nation has been required by law. The 2010 Census will be the 23rd since 1790.

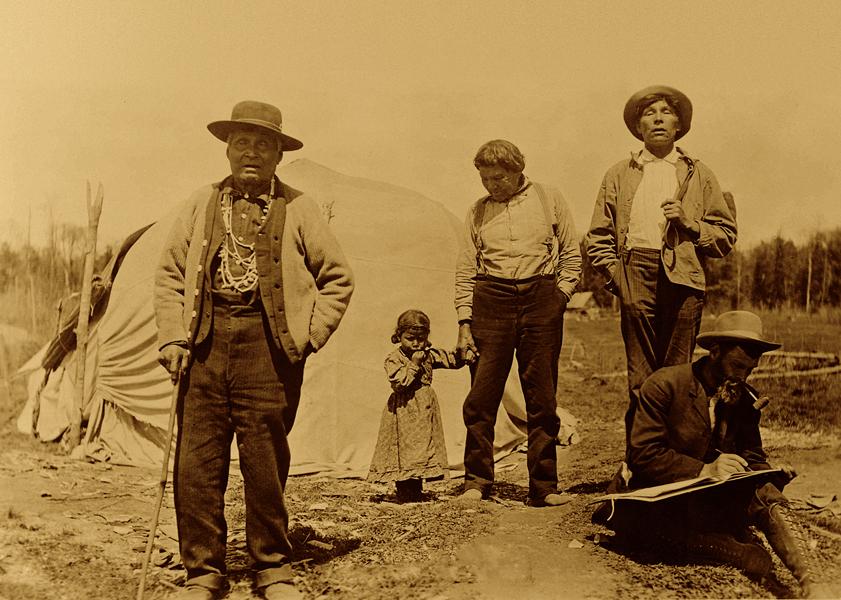

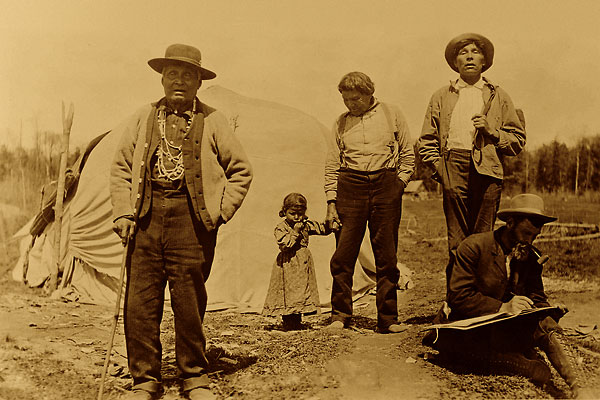

Census takers counted the people who lived in each dwelling as of June 1 of the current year. In 1870, census takers received two cents per name they added to the population schedules. For two cents, they wrote down each person’s name, age, gender, birthplace, the parents’ birthplace and occupation; and whether each person could read or write, was in school, or was blind, “deaf and dumb,” “idiotic” or “insane.” Travel expenses counted as 10 cents per mile.

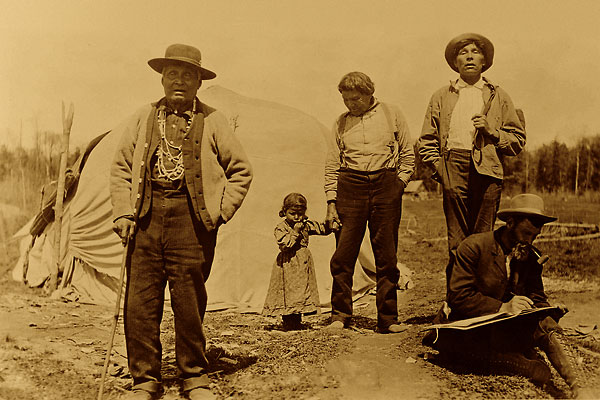

Taking a census in the West involved long hours and days of travel between populated places. Enumerators sometimes stumbled on isolated groups of travelers and started pages with headings such as “Camp 7th Cavalry,” “Wagon Camp” or “Gold Camp, Dragoon Mountains.” One could hardly imagine a lonelier place in 1880 than Starvation Stage Station, in Sweetwater, Wyoming. The sole inhabitant of the station, on the otherwise entirely empty page of the census form, was Edward Brant, listed as a “laborer.”

The census taker handling Barton and Rush Counties, Kansas, in 1870 noted that he was accompanied by a “strong escort of U.S. soldiers to protect me from hostile Indians.”

The 1860 Census in the Arizona Territory has numerous marginal notes by Assistant Census Marshal D.J. Miller. Some explain why the district had fewer people when Miller filed his papers than when he had recently counted the local population. These unfortunates included “Mr. Ward since killed by Indians,” one John Power who was “assassinated” by his employees and another man who was “probably dead from wounds received by hostile Indians soon after I left his farm.”

A macabre addition of Miller’s concerns the $1,100 in personal property held by a farmer named Boca Arriba Aquila; it included two “Yuma Indian scalps with long plaited braids” valued at $100 each.

M.H.W. Wheeler, a U.S. marshal, handled the census in Davidson County, Montana, in 1870. Explaining why his paperwork was late, he wrote on one census page, “I remained at Ft. Peck 8 days taking care of my wound and trying to get a boat crew to go to the mouth of the Yellow Stone.”

Western Legends and Ordinary Folks

An interesting aspect of the census is finding glimpses of Western characters, famous and otherwise. The 1880 Census in Arizona, for example, included many of the participants in the Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral, which would take place a year and a half later.

On June 2, 1880, a census taker visited the home of Virgil Earp in Tombstone. Virgil told the enumerator that he was a farmer. Also in Virgil’s household were his wife Allie; his brother Wyatt S. (also said to be a “farmer”), aged 32; Celia Anne “Mattie” Blaylock, who is named as “Mattie Earp” and recorded as Wyatt’s wife (they were not married, but people tried to look respectable when the census taker came calling); another brother, 39-year-old James C. Earp, a saloonkeeper; James’s wife Bessie; and their daughter Hattie.

In 1880, Doc Holliday was in Prescott, Arizona Territory. The census accurately listed him as a 29-year-old dentist who was born in Georgia.

Of the Clantons, Newman Haines Clanton (“Old Man Clanton”) was still alive at age 64. The census marked him in the “Village of Charleston” in Pima County as “N.H. Clanton,” whose occupation was “keeping dairy.” In the household were his sons Phineas, a freight driver, and William H. Clanton, often known as Billy, whose occupation was also “keeping dairy.” Newman Clanton was killed in 1881, before the O.K. Corral gunfight during which Billy and the McLaury brothers were killed. Billy’s brother Isaac “Ike” Clanton turns up in the 1880 Census in Yavapai County, Arizona Territory, as a farmer.

In 1880, Robert F. (“Frank”) McLaury and his brother Thomas C. were each listed as a “stock raiser” in the Babocomari Valley of Pima County.

Also visited by the census in Tombstone were Edward Benson and John Montgomery, whose occupations were listed as “Keeping L. Stable.” The name of their business? It was the O.K. Corral.

Bat Masterson turns up in Dodge City, Kansas, in 1880, as a “laborer” named “W.B. Masterson,” aged 25 and living with 19-year-old Annie Ladue, whose relationship is given as “concubine.” On the same page was Bat’s brother James, the city marshal; he was also living with a concubine, whose name was given as Minnie Roberts. A long way in space and time from Dodge City in the 1920 Census, Bat Masterson was recorded as a newspaperman, living in Manhattan with his wife Emma.

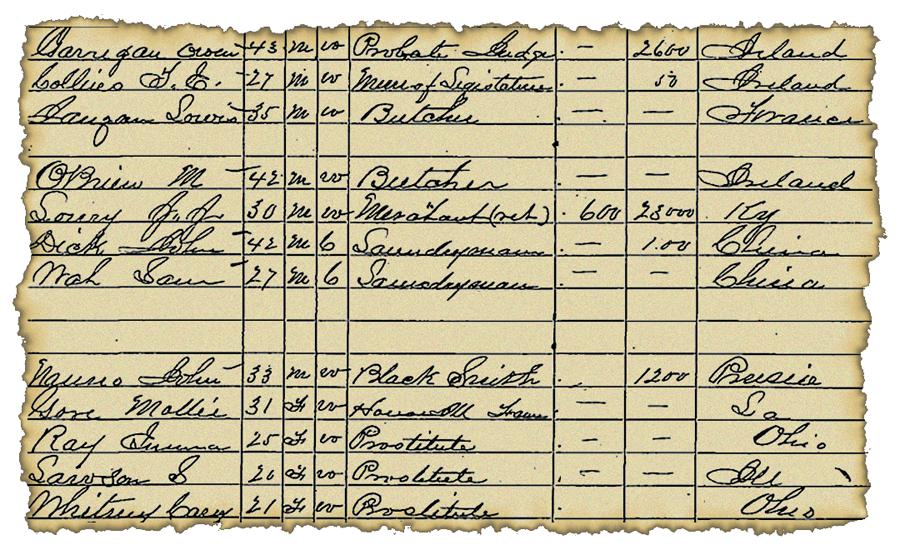

When surveying the inhabitants of a brothel, each resident might be noted as a “prostitute” or her work euphemistically rendered as “actress,” “hurdy-gurdy girl” or “sporting.” The wiseacre who compiled the 1870 Census in Fort Harker, Kansas, detailed a rather dubious household. Headed by a one George Palmer, whose occupation was given as “farmer,” a note to the side of dwelling #90 reads “house of ill fame.” The occupations of the women living in the house included “Diddles,” “Does Horizontal Work,” “‘Squirms in the deck” and “Ogles fools.”

Cowboys appeared on the census, but their occupation might be noted as “herding cattle,” “stockman,” “stock raiser” or “laborer.” Hotel guests enumerated in Dodge City in 1880 included men whose occupations were given as “driving cattle” or “raising cattle.”

Quite a few Western outlaws turned up in the census. Emmett Dalton appears on a Kansas census page in 1900—as an inmate at the Kansas State Penitentiary. By 1910, Dalton was free and living in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. In the space listing his occupation is the inscription “own income.”

Frank and Jesse James showed up under their real names in Missouri in 1850 and 1860. On September 28, 1850, the family of Robert and Zerelda James in Clay County included their children, “Franklin,” aged 10, and “Jesse R.,” aged four, and their baby sister Susan (with her age of nine months written in the usual census fraction of 9/12 of a year). Robert James was listed as a “B[aptist] Preacher” with $2,100 in real estate. Although he was listed, the elder James was not home. He had gone to California for the Gold Rush and, in fact, was already dead by the time the census taker reached his door in Missouri.

In 1860, Zerelda was married to Reuben Samuel, a prosperous farmer. Frank appears as “Alexander James,” aged 16, along with “Jesse W.,” aged 14, and their sisters Susan and Sarah, aged 10 and one, respectively. Such oddities—as the changing of Jesse’s middle initial and Frank’s aging only six years between 1850 and 1860—are examples of fairly common census errors. (Born in January 1843, Frank was actually seven in 1850 and 17 in 1860.)

Harry Longabaugh, the Sundance Kid, shows up in the 1891 census of Alberta, Canada. At 25 years of age, the future sidekick of Butch Cassidy was working as a horse breaker.

Where to Find Census Records

Some census records can never be found. Nearly all of the 1890 Census pages were lost in a fire in 1921.

Microfilmed census reels are available in local history and genealogy sections of many libraries.

Online genealogical services such as HeritageQuestOnline.com, Ancestry.com and Footnote.com offer access to census rolls to their paid members. (Your library might subscribe to one of these services.) FamilySearch.org, a genealogical site run by the Church of Latter-Day Saints, has some census images and census indexes available for free perusal. You can also check Internet sites such as the U.S. Genweb Project at USGenWeb.org, and check for state or county censuses that interest you.

Censuses up to 1930 are open to the public; the 1940 Census will be available in 2012. And the upcoming 2010 Census that we’ll be included in? Our data will be confidential for 72 years, so we’ll have to wait until 2082 to see it.

David A. Norris lives in Wilmington, North Carolina, and specializes in researching Civil War history.