The steam from the volcano diffused the dawn as the cattle drive reached the shoreline where the Pacific Ocean rolled into Kawaihae Bay.

While some of the cowboys herded the cattle into stonewalled pens on the beach, others dismounted and removed their saddles. They carried them to safety in the tall dry grass beyond the surf line. They took off their boots and placed them beside their saddles. Salt water plays hell with leather.

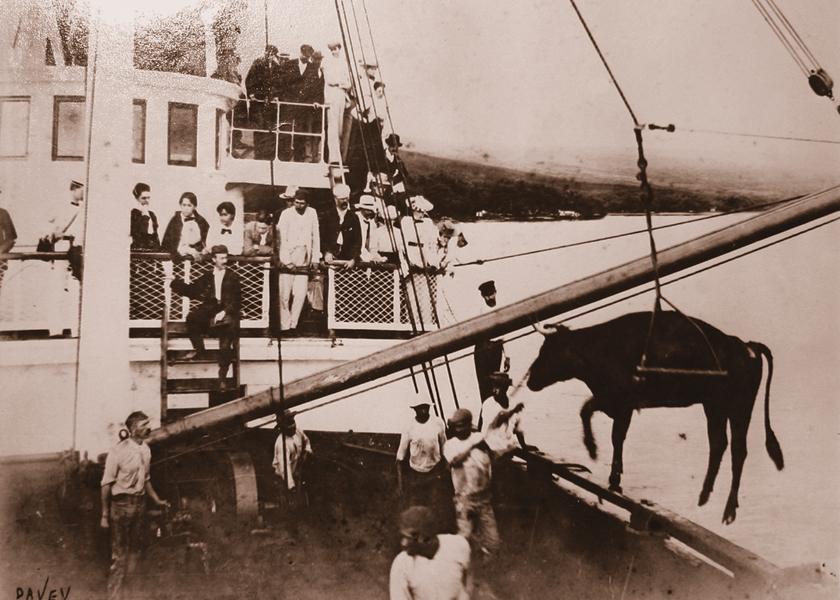

The cowboys carried wooden saddles back to their horses, cinched them in place and climbed aboard barefoot. Sailors rowed a long boat from the freighter anchored offshore and held position just beyond the breakers. The foreman gave the word and a cowboy tossed his hemp lariat and lassoed a steer, dragging it through the surf to the boat where the sailors tied the steer by the horns to the gunnels, taking care to keep its head high so it wouldn’t drown. When both sides of the boat were lined with cattle the crew maneuvered the boat around and rowed out to the freighter where the cattle were winched aboard one by one and placed in pens on the deck.

The work was hard and slow. The horses were accustomed to swimming in the surf, but for the cattle, this was their first and last swim. Sharks were a common sight, but the cowboys knew how to fend them off from the cattle. The work lasted until the last of the herd was safely aboard the ship. The ship then weighed anchor and steamed to Honolulu and the slaughterhouse.

On the beach, the cowboys replaced the wet saddles with their dry ones and rode back the way they came, to the ranch that was both their home and their livelihood. They rode slowly, easily and together, like cowboys have done all along throughout the West. They had brought their herd to the shipping point. Yet these were not your typical cowboys, and the ground they covered was not a typical Western landscape.

They were Hawaiian cowboys, paniolo, and a part of a tradition that began in 1793, with the introduction of cattle to the islands, and continues to this day. The challenges and rewards of cattle ranching in the Hawaiian Islands are the same faced by cattle ranchers everywhere. And like cattle ranching everywhere, the landscape and the people shape the tools and the trade to fit the circumstances.

Cattle ranching and the paniolo culture are strong on all of the major islands, but one of the best places to learn about its history is at the Parker Ranch in Kamuela. Hawaii’s oldest working cattle ranch offers numerous tours, including its “Cattle Country Tour” that shares the historical and operational areas of the ranch, most of which is not open to the general public.

How did Parker Ranch get its start? Our story first takes us to a midshipman serving under Capt. James Cook.

Vancouver’s Gift

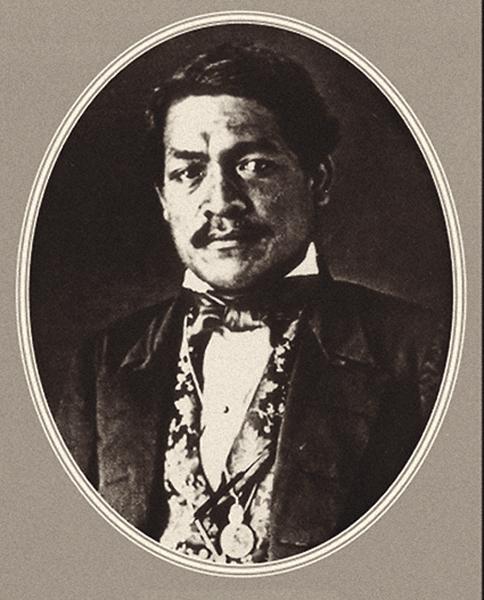

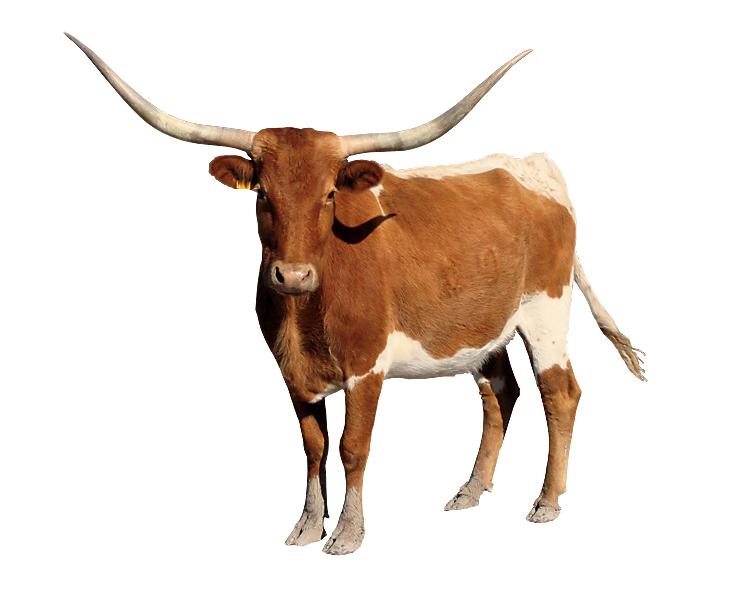

George Vancouver served as a midshipman with Capt. James Cook. While he accompanied his captain to the Sandwich Islands, the natives killed Cook in February 1779. Vancouver returned to the islands in 1793 in command of his own ship. Onboard he carried half a dozen California Longhorns he had obtained in Monterey on a voyage of approximately 2,000 nautical miles. He offered them as a gift to Kamehameha I.

As early as 1786, Hawaiian ports had become popular stops for whalers and commercial shipping as both a haven from the winters of the northern Pacific and as a resource for provisions. King Kamehameha I wanted to expand the commercial opportunities of the islands, so he accepted Vancouver’s gift of cattle. To protect the cattle and allow them to propagate, Vancouver advised the king to protect them with a kapu: a law carrying the death penalty for anyone who killed any cattle. During this period, in 1803 to be exact, the renowned Salem seafarer Richard Cleveland brought the first horses—mustangs from Spanish California—to the island of Hawaii on the brig Lelia Byrd and gifted these to Kamehameha I.

Over the next 20 years the cattle roamed the high grasslands of Waimea. Under their protected status, the cattle tore up planted fields and ravaged villagers’ vegetable gardens. Stone walls were erected to keep out the feral cattle, but they continued unabated until Kamehameha I lifted the kapu in 1815.

Parker’s Perfect Timing

Enter John Palmer Parker. The 25-year-old sailor from Newton, Massachusetts, arrived the same year that the kapu was lifted. He had fallen in love with the islands during previous visits, and he was determined to build a life there. Parker “armed with only a musket, was appointed … to kill wild Waimea longhorns. Three years later he bought two acres of land and married a great-granddaughter of Kamehameha named Kipikane, receiving 640 acres of land as a royal wedding gift,” reports Ilima Loomis in 2006’s Rough Riders: Hawai’i’s Paniolo and Their Stories.

Parker and others hunted the wild cattle, called bullocks, through the varied terrain of the island, across lava flows and through thick forests. They were after meat primarily, “but hides and tallow from these animals grew into an export industry of its own,” reports Dr. Billy Bergin in 2004’s Loyal to the Land: The Legendary Parker Ranch, 1750-1950. “Much of the meat went to ships in the form of salted beef.”

The animals were trapped in big pits, and then the hunters butchered them and preserved the meat with salt that they had carried up into the mountains on their backs. They packed the meat into barrels, which they hauled back down the mountains. Bullock hunting was time consuming, laborious and inefficient, even while the economic promise of cattle continued to grow. There had to be a better way.

King Kamehameha died in 1819. This same year, the missionaries arrived, and the islands’ religion, culture and society crumbled. Hawaii opened to whaling and settlement. King Kamehameha II died in 1824, succumbing to a measles infection at age 27. His younger brother assumed the throne as Kamehameha III. Around 1830, he sent for vaqueros to teach Hawaiians how to work cattle from horseback. Along with their knowledge of cattle, the vaqueros brought the tools of their trade—saddles, lariats, spurs and other gear—as well as their traditional working clothes, including their wide-brimmed hats, colorful ponchos and leggings. The vaqueros called themselves paniolo, and the name stuck.

The “Spanish Method” of hunting wild cattle involved roping a bullock and tying it to a tree for a day or two until the animal was too fatigued to fight its restraints. Then two paniolo on horseback led it to a corral where the slaughtering and butchering was done. If a tree was not strong enough to hold the animal, the paniolo would hobble the bullock by cross-tying opposite fore and hind legs. The animal could graze without getting far.

“A less labor intensive and safer alternative was the pini system. With this system, the bullock was pinned or joined with a closely tethered neck rope to a gentle ox for a slow six- to twelve-hour trip to the home corral. . . . A pini bullock or pin bull was usually a stag—a bull castrated after maturity,” Bergin reports.

Cattle ranching expanded to the point that, by 1847, the branding of hide became grounds for legal ownership.

Before the Great Mahele

Like other ranchers at the time, land was hard to come by. The Hawaiian king owned most of the available pastureland. This changed when King Kamehameha III abolished a feudal system of land ownership with the Great Mahele of 1858. This “division” permitted commoners and foreigners to own land.

Yet Parker Ranch predates the Great Mahele. Due to his friendship with Kamehameha I and his marriage to Kipekane, Parker was able to found his ranch in 1847. Parker, like intelligent cattlemen everywhere, focused on two main challenges: acquiring additional lands to support his expanding herd and improving the quality of his stock. With the strategic advantage of access to the seaport of Kawaihae, Parker focused his land acquisitions around present-day Waimea.

“Waimea was the jewel. With acre after acre of windblown grasslands stretching across a high valley, sweeping down the Kohala Mountains to the north and up the massive slopes of Muana Kea to the south and east—much of it less than a day’s ride from a good harbor at Kawaihae Harbor,” Loomis reports.

Livestock quality, however, presented Parker with a significant obstacle. He built his initial herd out of highly inbred feral cattle, which meant that it took nearly seven years for the animals to reach the market weight of 500 pounds.

The Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society proved instrumental in helping ranchers like Parker to bring seed stock from around the world. The challenge, of course, was keeping the feral bulls from breeding with the domesticated cattle. “By 1859, the wild cattle estimate of 12,000 head was nearly matched by domesticated cattle, estimated at 8,000,” Bergin reports.

The cattle were shipped to the main market in Honolulu. The strong currents between the islands made the voyage difficult and time consuming. Once the ships unloaded the herds, the scene resembled those in Wichita and Dodge City, Kansas, with herds driven through downtown Honolulu to the slaughterhouses, much to the consternation of the general populace. The demand for beef and beef byproducts of hide and tallow continued to grow and, with it, so grew the Hawaiian cattle industry.

Parker died on August 20, 1868. His son John Palmer Parker II and others carried on his legacy. Most notably, A.W. Carter became the ranch manager in 1887 for nearly 50 years. “Parker Ranch in 1932 held 327,000 acres of land in fee simple. It had a 26,000-head Hereford herd, including 400 bulls; and it had 1,000 Holsteins in its dairy operation, 2,200 horses and mules, 12,000 merino sheep, and 1,000 Berkshire swine,” Loomis reports.

The paniolo, meanwhile, adapted vaquero equipment and traditions to reflect Hawaiian climate and culture. The Hawaiian saddle is an example of this evolution. Both the Mexican and Hawaiian saddle “have a rawhide-covered tree with no attached leather covering the horn fork, bars, or cantle,” Bergin reports. The Hawaiian saddle had a unique addition. “A single piece of rawhide is draped over the horn, wrapped tight, and molded over the pommel, leaving a row of long braids on each side that held the cinch ring in place,” Loomis states. The paniolo consider their saddles stronger because of this addition. The paniolo also employed a mochila, a leather apron that draped over the saddle with a hole for the pommel and a slot for the cantle.

The leather provided comfort and protection to the rider. Another feature common to the Mexican and Hawaiian saddle are the stirrup guards, or tapaderos.

In personal apparel, vaqueros adapted to Hawaii. They abandoned their leather or hard-felt sombreros for the light and well-ventilated papale lauhala (woven padanus hat) with a wide brim and high crown. “The land that a Hawaiian paniolo had to work varied from sweltering volcanic slopes to wet mountain peaks, places where heavy mists and piercing rains could spring up at any moment. Therefore it was most practical, if not necessary, for every paniolo to have a hat as part of his gear; in most cases woven by his wife, by a family member or a sweetheart,” reports Lyn J. Martin in 1987’s Na Paniolo o Hawai’i. Paniolo would often festoon their hats with a flowered lei.

Last of the “Old Vancouvers”

The livestock industry has changed everywhere, but most certainly it has changed in Hawaii. Cattle no longer are tied by the horns to the gunnels of long boats en route to the market in Honolulu. They are herded down wharves and aboard ships built for that purpose.

The last of the “Old Vancouvers,” the descendants of the feral progenitors of the cattle industry, are gone; although hundreds of wild cattle roam deep valleys and forests, and are considered big game prize by hunters. In place of the feral cattle, purebred, domestic cattle graze in smaller, fenced pastures.

You’ll no longer find a slaughterhouse on the islands. Hawaiian beef is shipped live to the mainland for processing.

Fewer ranches employ fewer paniolo, just as on the mainland, fewer ranches employ fewer cowboys. Yet, people still demand beef.

As long as there are those who savor a good rib eye steak, then there will be places like the Parker Ranch and people who work the land, who tend to the cattle and who sustain the tradition and culture of their world. There will always be the paniolo.

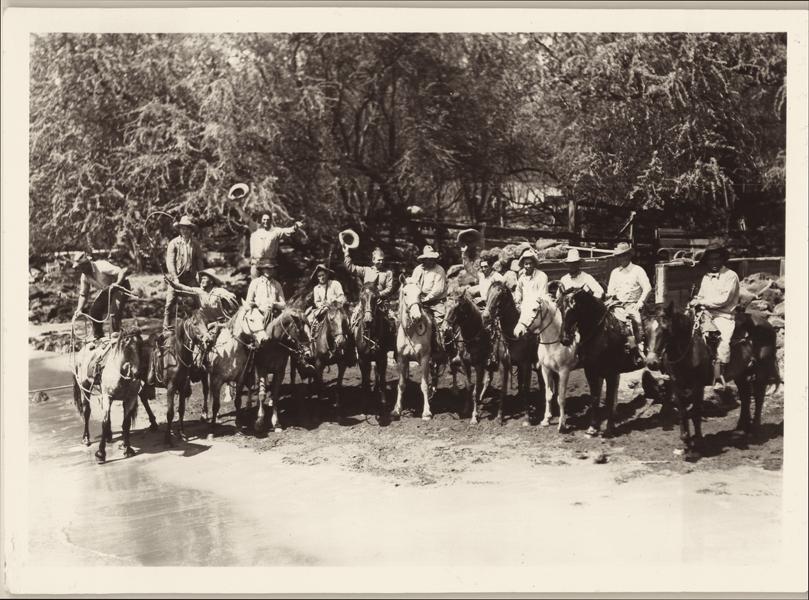

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Paniolo Preservation Society –

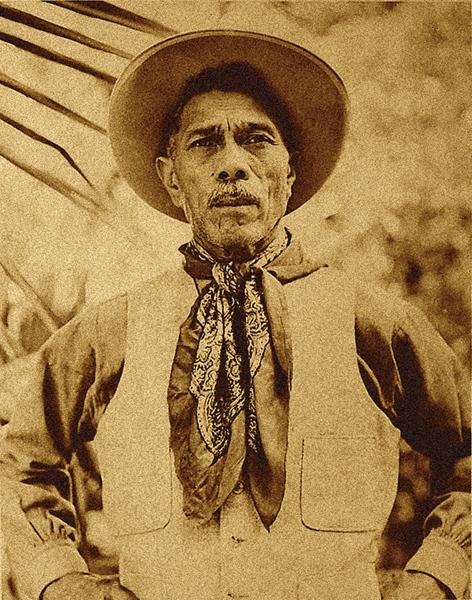

In August 1908, at the Frontier Days Rodeo, in Cheyenne, Wyoming, a paniolo by the name of Ikua Purdy won the World Steer Roping Championship.

Ikua Purdy, John Palmer Parker’s great grandson, was born at Parker Ranch on Christmas Eve in 1873. His career as a paniolo began with the Parker family.

In 1907, Hawaiian businessman Eben Low attended the rodeo in Cheyenne and returned to the islands convinced that Hawaiian cowboys could do better than what he’d seen of the cowboys in Wyoming.

Three paniolo—Ikua Purdy, Archie Ka’au’a and Jack Low—sailed to the mainland and made it to Cheyenne in time to borrow horses and compete. Unlike today’s calf roping competitions, riders at that time lassoed full-grown steers. Ka’au’a came in third place, while Low came in sixth. Purdy roped, threw and tied the steer in 56 seconds for the win.