Heading east on Highway 380 from Post, Texas, to the ghost town of Clairemont is a 45-minute drive through a wide open and sparsely populated country. You’ll find nothing but range land in this remote part of West Texas.

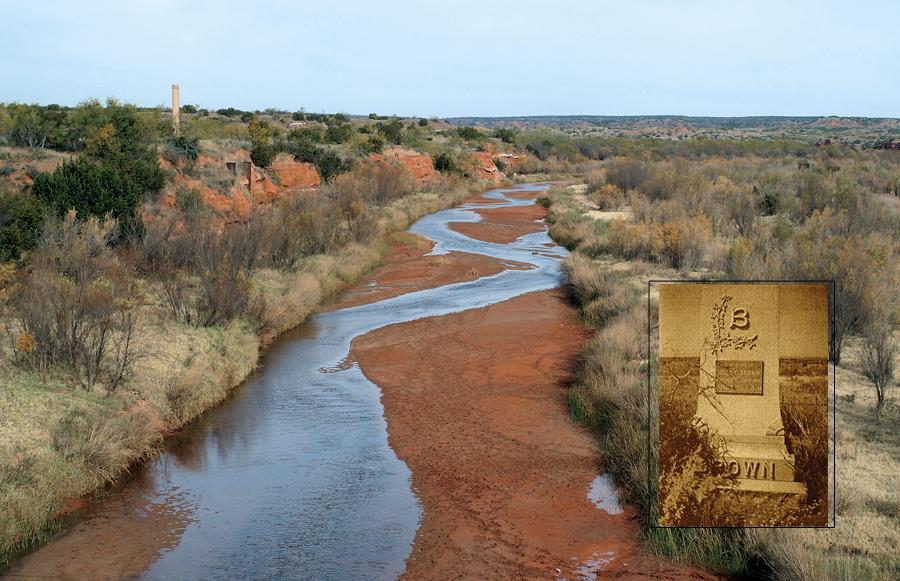

About eight miles before reaching Clairemont, and not visible from the road, stands a monument on the old “24 Ranch.” It is shrouded in mystery, reading, “In memory of Boley Brown who died at this place June 7, 1911, at 7AM.” Nothing more. Nothing less.

The monument marks the spot in the pasture where an ailing Brown died; he had been on his way to the doctor. That this marker remains even to this day is a testament to his standing in the community of Kent County. Brown became a “cattle king” at what was then the edge of the Texas frontier, yet little has been written about him.

Brown, attracted to the area by his uncle, was among the first cattlemen who came to these Comanche-infested plains right below the Llano Estacado or staked plains; now the “Caprock.” In this arid and unforgiving land, Kent County was home to 92 cow herders living in 22 cow camps. In 1880, only one adult female lived in the area, and she was married with two children.

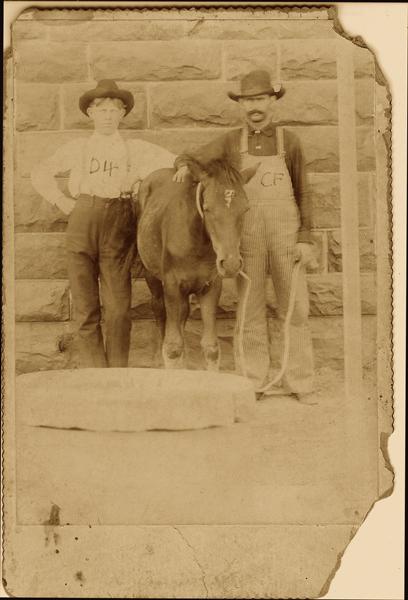

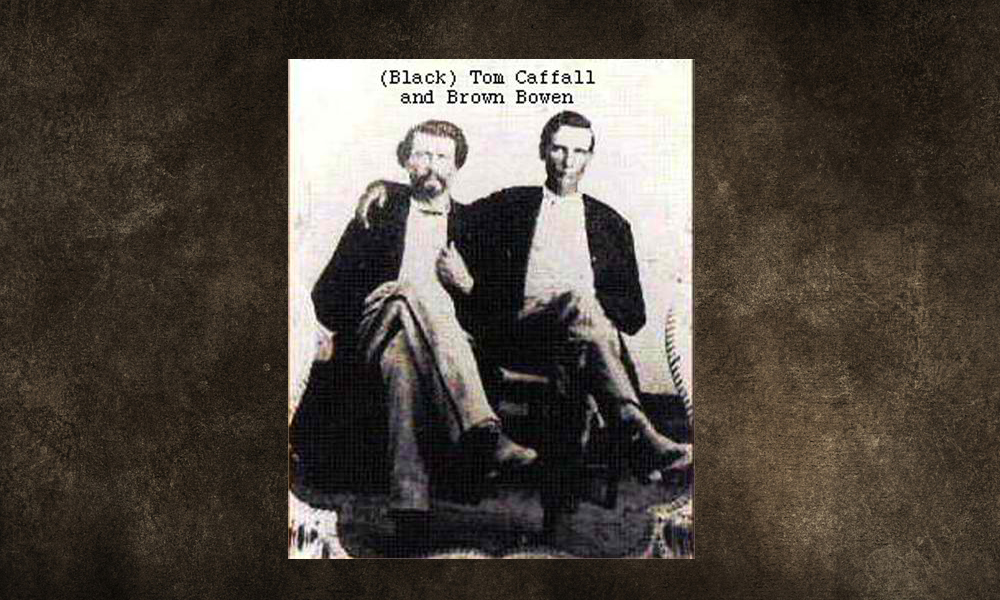

A descendant of C.O. Fox, Don Jay, wrote an article titled “Bad Blood,” which shared the story of the 1901 gunfight between Jeff Hardin and John Snowden in Clairemont, then the county seat. Jay’s article featured photographs of the locals who often settled disputes with guns rather than in the courts. One showed the livery barn in Clairemont, where Hardin died in the gunfight. Another, John Snowden—the man who killed Hardin.

When I inquired about the photographs, Jay told me he no longer had them. His parents had leased their ranch, and the renter allowed his children to break into a trunk containing the photographs and most of the contents were destroyed.

One day, not long after our conversation, Jay got in touch with me. While cleaning up a storage area at his home, he had come across a box his brother sent him that he had never gone through. He opened it and saw the photos he believed had been destroyed at his parent’s ranch.

Boley Brown, his wife Matt Garretson and the folks they knew while operating their 24 Ranch come to life in these photographs. It is my privilege to tell the story behind the cattle king who warranted a lasting monument in the Texas Panhandle.

Photo Gallery

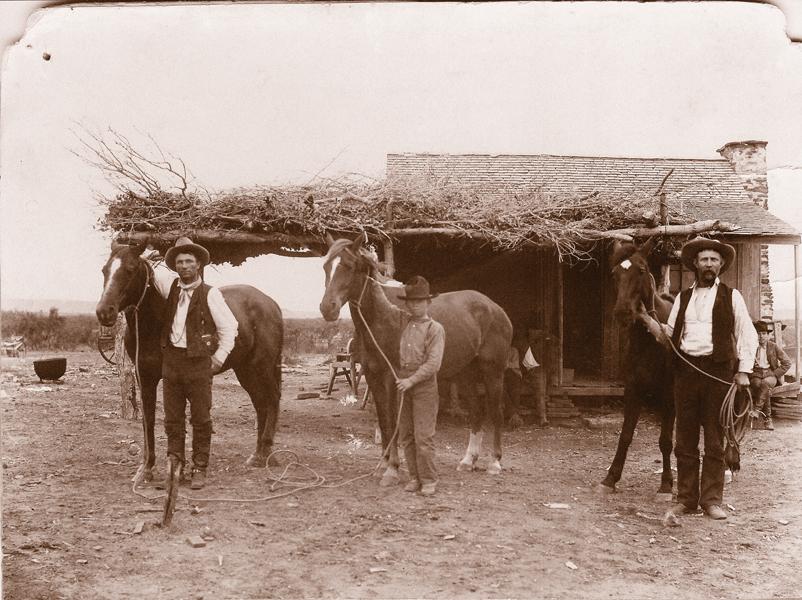

From left are Boley Brown, his son Chalk and Ingram D. “Pete” Scoggins. Brown and Scoggins first owned the B Bar S ranch as partners. They registered the brand in 1888. The partners later purchased a cattle herd from Clay Mann branded with the number 24. They kept the brand and registered the 24 on May 28, 1897. The three horses shown above wear the 24 brand. Note the brush arbor extending from the porch of the snug little cabin. This was considered fancy compared to the dugout that most people lived in during those early years.

Boley Brown was born in 1857 in either Illinois or Texas, depending on the source. Census records state he claimed Texas as his home state. Boley’s Uncle “Smokey” Brown established the first cow camp in Garza-Kent Counties in 1878, on Yellowhouse Creek (known today as Yellow House Draw, a dry tributary of the Brazos River); he helped give Boley his start. That same year, Boley married an Arkansas girl, Martha Alice “Matt” Garretson. In 1880 Boley herded cattle for the “Jackson camp” in Kent County but struck out on his own about that time. Matt drove a wagon across the rolling plains, while Boley looked for unbranded cattle on horseback. Once Boley found one, Matt would drive up close, head to the back of the wagon and remove a hot “B Bar S” branding iron from an iron pot that had a fire built inside it. (They made a firewall by loading the wagon bed with sand.) Boley would then take the hot iron and burn the brand into the hide of the cow.

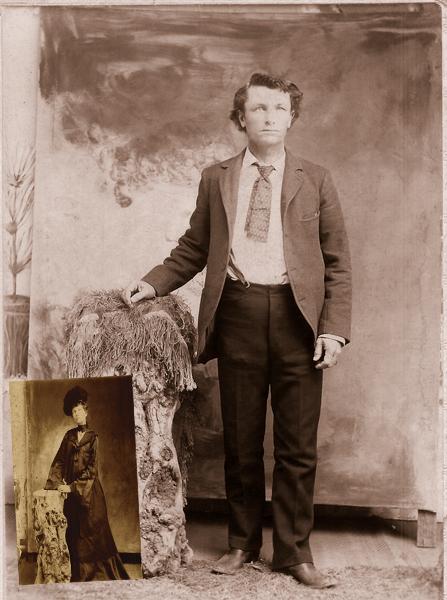

Charlie Fox (at left) was born in Parker County. Boley & Matt Brown took Charlie and his family in when his father died. He grew up on the 24 Ranch; at the age of nine he went on his first cattle drive to Amarillo in 1884 as a “Wood Hoodlum.” He was paid $10 a month. He made extra money by washing socks for cowboys at ten cents a pair and sold them flour sacks at ten cents a cloth; the cowboys wrapped the cloth around their boots to keep their feet warm during the cattle drive.

– All photos courtesy Norman W. Brown –

The saloon at the C.O. Fox Stable in Clairemont, Texas, was owned by Jeff Hardin, the younger brother of gunfighter John Wesley Hardin. (His saloon was located on the right behind the buggy.)

While working at his saloon, in 1901, Jeff was killed in a gunfight by John Snowden, a cousin to C.O. Fox, who, incidentally, was married to Jeff’s cousin Gussie. Jeff took three rounds; one to the heart and one in each leg. He had a murder charge hanging over his head. While working as a scalper, Jeff had killed a rustler (or so he thought) south of Clairemont at “Ennis Creek.” When Jeff discovered the victim was unarmed, he tried to convince Snowden to lie for him. Snowden refused and ended up shooting Jeff in what was believed to be a standup gunfight (no known witnesses). Snowden confessed to the killing, made bond and the murder charge was later dismissed.

Snowden must have thought highly of Boley Brown; he named one of his two daughters Boley.

In the 1896 photo Hardin’s killer, John Snowden, is shown in the front row, at right. Will Rogers is seated beside him and behind him are Will Snowden and Bill Neeley.

The cowboys pictured in front of the stable are (below, from left): John Sampson, Mace Hunter, Will Rogers, C.O. Fox, Gee McMeans, Jack Rogers, Maxie Williams, Willis Rodgers, Dick Jay, Ed Underwood and Lee Byrd, with Dick Sampson in buggy. The boys standing on the roof are Gene Selmon and Burley Sampson. The two boys standing at right are unidentified.

Fannie Hardin, cousin to Jeff and John Wesley Hardin, married Charlie Fox. Her husband told of a neighbor’s cattle getting mixed in with his, while he, Fannie and her sister Martha were riding to town. Martha removed her saddle and mounted bareback so she could help Charlie get the cattle out of his pasture. For a woman not to ride side saddle would have been a terrible breach of protocol had it occurred in public. Perhaps that is why she stands beside her horse in this photo instead of mounting it; the saddle shown here is one normally used by men for riding astride a horse.

Cowboys on the 24 Ranch having breakfast during spring roundup. They made trail drives to Kansas and later to Amarillo, Texas, until at least 1889 when one was made from Paint Rock. As the rails came closer to Kent County, cattle were shipped from places like Post and Justiceburg Station.

The 24 boasted thousands of cattle and 200 excellent cutting horses. Brown became the owner of more than 100,000 acres of land in Kent County. In the beginning it was just open range. He and Scoggins later leased the land from the state but never paid a dime of rent. When the homestead law came about, ranchers were allowed to file on four sections of land for a filing fee of $50. After three years they owned it. Boley’s cowboys filed on four sections and later signed them over to him. He paid them $100 each. A small price to pay for four sections.