The frontier was a great place for a doctor to practice….and that’s what many of them did…..practice. In 1880 Tombstone, a town of 2,000 had a dozen doctors but eight of them didn’t have a license. It was a place where they could improvise at will working without the same restrictions and restraints as their eastern colleagues.

They treated all kinds of ailments from broken limbs, gunshot and stab wounds, rattlesnake bites, and scorpion stings. The most common involved explosives, wagons and horses.

They delivered babies, fought smallpox, pneumonia, and diphtheria. At times they had to be creative. One wrote “I slit the throat of the child choking with diphtheria, opening the windpipe and kept it open with fishhooks.”

Most of the time, surgery was performed at the scene of the accident. There was total lack of cleanliness, due mostly to the lack of knowledge. Little was known about germs. Carbolic acid was usually the sterilizer but strong whiskey also worked. But, anesthetics and sterilization were rare or non-existent. One told of operating while sitting on a tree stump while his patient was sprawled over a whiskey barrel. One hand did the cutting while the other shooed away the flies.

Another used his 200 lb. office boy to sit on the patient’s head to keep him still during the surgery.

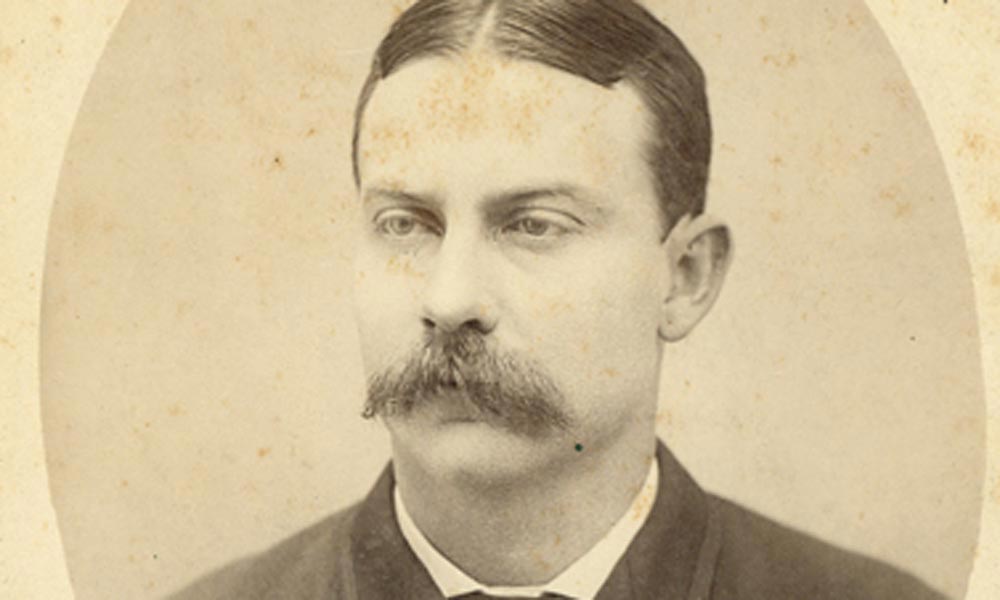

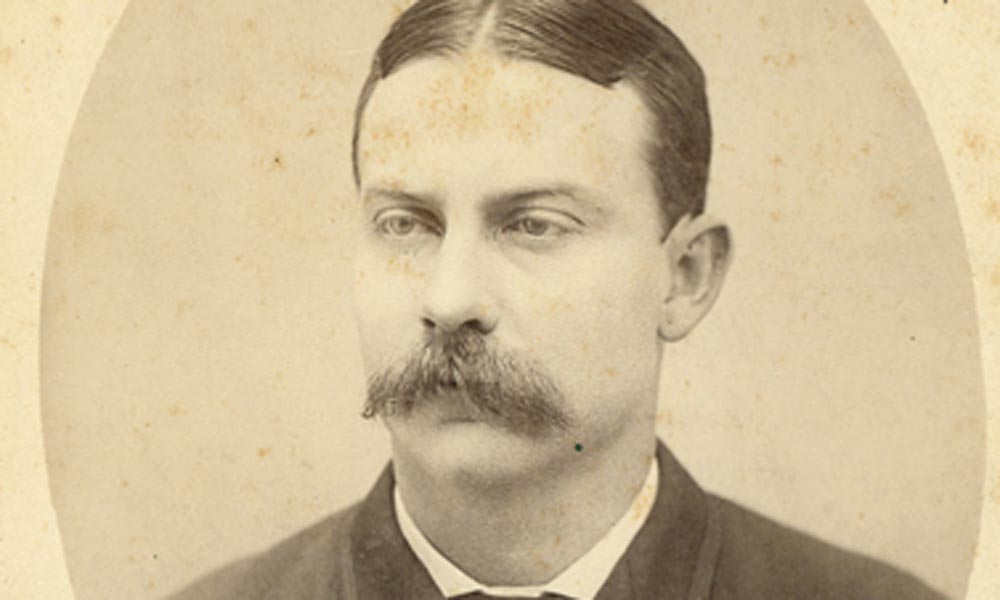

One of the most famous frontier practitioners was Dr. George Goodfellow. He gained notoriety shortly after he hung up his shingle on the second floor of the Golden Eagle Brewing Company. The building burned soon after in the “Big Fire” on June 22nd, 1881. It was rebuilt as the Crystal Palace. It also housed the office of U.S. Deputy Marshal and town Marshal Virgil Earp.

Tombstone was a great location for practical experience and before long he was known nationwide as the “Gunshot Physician” for the articles he published on treating them. He concluded that a gut-shot victim from a Colt .45 was invariably fatal. He wrote “Gunfighters’ maxim is ‘shoot for the guts,’ knowing that death is certain, yet sufficiently lingering and agonizing to afford a plenary sense of gratification to the victor in the contest.”

He also published articles on rattlesnake and gila monster bites. There were rumors at the time the bite of a gila monster was fatal but he disproved that theory in 1891 when he provoked one to bite him on the finger. He was sick for a few days but made a full recovery.

In Northern Sonora he was known as “El Doctor Santo,” the Blessed Doctor, following his heroic efforts to aid them following the great earthquake of 1887.

Whether it was a lonely outlaw hideout treating some cattle rustler or in the home of a poor Mexican family Doc Goodfellow always responded. He could even drive a steam locomotive as well as any engineer or crawl down into a smoke-filled mine shaft to rescue trapped miners.

Following the famous gunfight near the OK Corral on October 26th, 1881 he performed autopsies on the McLaury brothers and Billy Clanton. In March, 1882 he attended to Virgil Earp’s crippling wound by assassins in December, 1881 and Morgan Earp following his assassination by the Cow-Boy element.

Doc also treated Curly Bill Brocius after Lincoln County War veteran Jim Wallace shot him in the cheek and neck over in Galeyville.

After Billy Clanton was mortally wounded at the so-called Gunfight at OK Corral he asked that his boots be removed because he didn’t want to “die with his boots on.” Doc was there and kindly obliged the youngster.

He was also treating the survivors of the battle, Virgil and Morgan Earp, who’d both been wounded.

When the five outlaws, Omer “Red” Sample, James “Tex” Howard, Dan Dowd, Bill Delaney and Dan Kelly, were executed for the Bisbee Massacre in March 1883, doc did the autopsies.

John Heath, the inside man was given a separate trial because he wasn’t present at the massacre. After he was given a prison sentence an angry mob stormed the jail and lynched him from a telephone pole on Toughnut Street. Doc also autopsied Heath,

Legend has it Goodfellow’s report said Heath died of “shortage of breathing while at a high altitude.”

It would be Tombstone’s only lynching.

Doc Goodfellow had the distinction of being the first physician known to operate successfully on abdominal gunshot wounds, and was praised as the first to perform a successful “perineal prostatectomy” in 1891.

During the big fire in June, 1881 Tombstone Chronicler, George Parsons was critically injured while tearing down a balcony to prevent the fire from spreading. A piece of wood flattened and deformed his nose. Doc skillfully reconstructed Parson’s nose then refused payment because George was performing a public service.

During waking hours the doc could usually be found in one of two places, his office or downstairs in the saloon where he was promoting a wager or sporting event. In 1872 he’d attended the U.S. Naval Academy briefly and was their boxing champion before being dismissed after a fight and hazing incident with a fellow midshipman. That was when he decided to go to medical school.

In a city full of colorful characters, Doc Goodfellow ranked with the best of them. Among his other talents, the pugnacious doctor was also hard drinker and in notorious lady’s man.

He practiced in Tombstone for eleven years before moving his practice to Tucson following the death of his good friend Dr. John Handy.

In 1898 when the Spanish-American War began, he joined General William Shafter’s staff as a civilian volunteer and went to Cuba. His fluency in the Spanish language made him a valuable asset to the general. It was Doc Goodfellow, along with a bottle of Ol’ John Barleycorn, that he kept in his medicine bag who helped negotiate the Spanish surrender. Following the capitulation, Spanish General Jose Toral gave the doctor and one assumes the whiskey, credit for talking him into it.

There’s no getting around it, Doc Goodfellow’s lived a full life, very different from that of an ordinary physician on the frontier.