Victorians had a bizarre fixation with premature burial—a fear that wasn’t just hysterical, because poor medical knowledge meant that sometimes ill-trained physicians pronounced an unconscious or comatose patient dead. Sometimes the revival came at the most embarrassing moment—like the funeral. Every one of these incidents got widespread attention in newspapers, so it appeared it happened far more than it actually did.

But the result was stunning. Groups like the “Society for the Prevention of People being Buried Alive” changed the way death was handled. The deceased were left lying in their caskets for days or weeks before burial, to be certain of their demise.

Another reaction was to put crowbars and shovels in the casket, so if the person revived, he or she could dig out. Some caskets had a pipe that went through the ground into the casket as a way to communicate if the casket held a live person. It’s said that wealthy families had servants sit by the pipes and listen for calls of help.

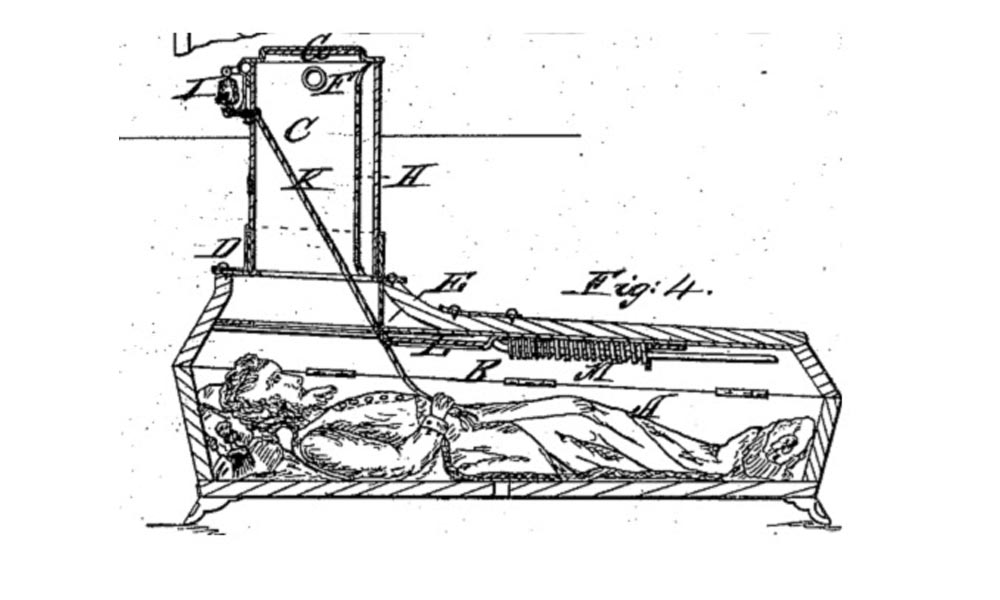

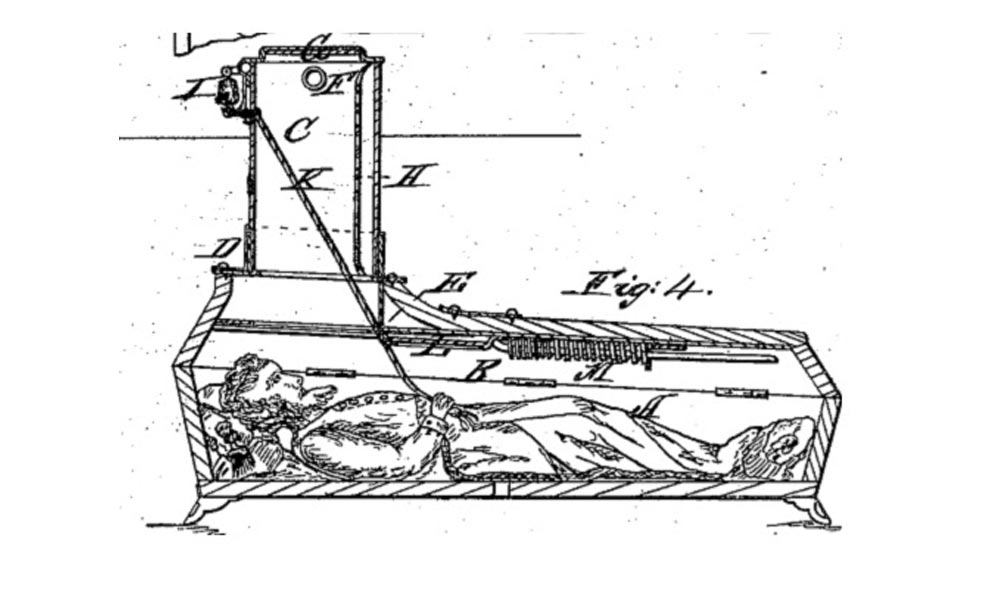

But the most popular method to help the buried alive was the Bateson Revival Device, advertised as “a most economical, ingenious, and trustworthy mechanism, superior to any other method, and promoting peace of mind among the bereaved at all stations of life. A devise of proven efficacy, in countless instances in this country and abroad.”

It was an iron bell mounted on the lid of the casket just above the head of the deceased. It was connected to a cord through the coffin that was placed in the dead person’s hand, “such that the least tremor shall directly sound the alarm.”

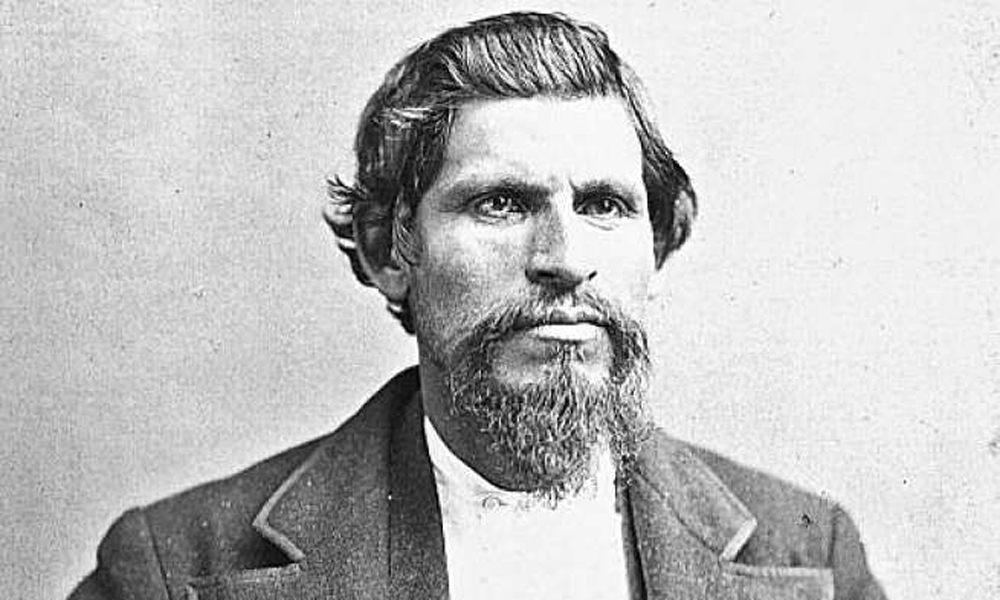

There’s no record this bell actually saved someone who’d been buried alive, but it was a big seller for years and made its inventor, George Bateson, a rich man.

Alas, poor George was so obsessed with the idea of being buried alive, he committed suicide in 1886 by setting himself on fire.