Ominous clouds threaten rain as I pull off Highway 80 near the Arizona-New Mexico border at the Skeleton Canyon monument. I debate whether or not I should drive to the actual site where the Apache Wars ended when Geronimo surrendered in 1886.

Louis Kraft’s story echoes through my head—no, I didn’t have a margarita at the Gadsden Hotel tavern in Douglas, Arizona. If you don’t know Louis Kraft, you should, because his book Gatewood & Geronimo is required reading to understand the Apache Wars. As an Apache Wars historian, Kraft ranks up there with Angie Debo and Edwin R. Sweeney. As a tourist, well, here’s his tale:

He’s traveling with his young daughter across southern Arizona, hell-bent on going to Skeleton Canyon and seeing the historic site, not just this rather ugly marker I’m staring at. So he drives into the hinterlands and comes to shallow water covering the road. (Being holier than thou, I, of course, know better than to drive across water in the West, but Louis lives in Los Angeles, and, well, he’s obsessed with Geronimo.) He tries it. Gets stuck. Gets stuck more. No cell phone signal out here, it’s a long walk to nowhere and there’s his daughter to think about. So Louis becomes superman; he grabs blankets, anything he can find (but not his daughter) to get traction for his wheels. Perhaps the ghosts of Apache warriors Lozen and Nana give him a push, but he makes it out of the bog and gives up on his quest. He’s bound for the hotel in a mud-splattered car that looks like it has been on an African safari for 10 years, and now he’s thinking, “Man, how cool is this? Wait till everyone sees my car!” But this is monsoon season; a thunderstorm blows in, and before Louis can show off his daring, his car is spic-and-span.

So there’s my dilemma: Skeleton Canyon or Lordsburg, New Mexico? Alas, I lack Louis’s daring (he would have made a great scout for Al Sieber—till he drowned in a flash flood), and coffee at Kranberry’s Family Restaurant in Lordsburg sounds inviting.

Besides, whenever I drive along I-10 to Lordsburg, I expect to see a stagecoach barreling across the Lordsburg playas, with the Ringo Kid’s Winchester dropping countless Apache warriors. Maybe this time I will.

Forting Up

Long before I saw Stagecoach, Broken Arrow or Ulzana’s Raid, the Apache Wars fascinated me. So has Arizona. I often wonder why I don’t live there, but, then I remember it has something to do with rattlesnakes and 423-degree summers.

Yet if you think we have it rough today (getting stuck in puddles of water, eating too much at Tucson’s Mi Nidito), imagine how rough soldiers stationed in Arizona during the conflict with the Apaches had it. You get a pretty good glimpse of those hardships at Fort Lowell Museum, an Arizona Historical Society branch located at a public park in Tucson.

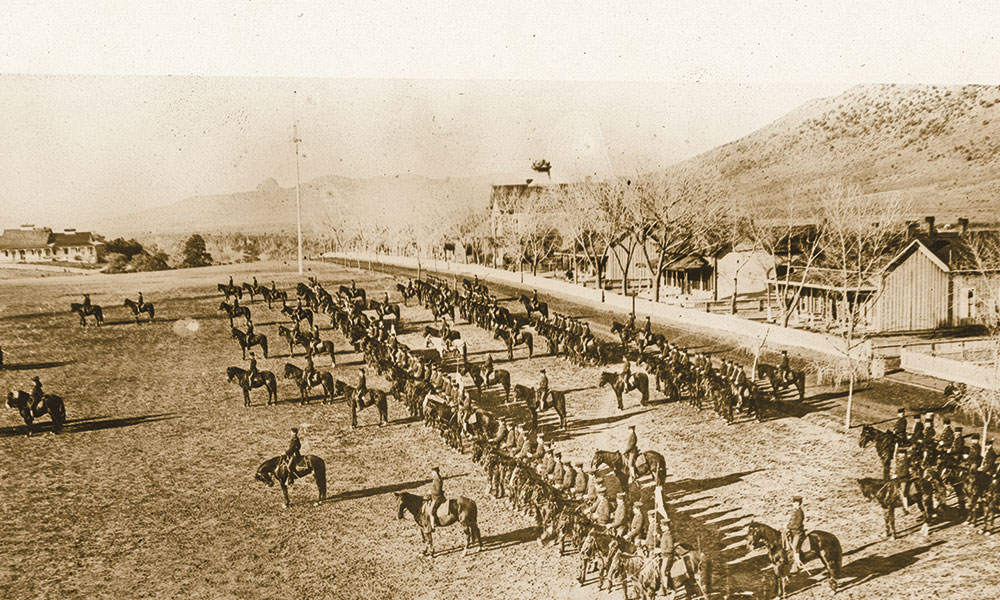

The army established Fort Lowell in 1873—an earlier post, established about seven miles away in 1866, was moved because of health reasons. The museum, which features various exhibits chronicling military life, is housed in the reconstructed commanding officer’s quarters. Before the army abandoned it in 1891, the fort housed troops from the Second, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Cavalry and the First, Eighth and 12th Infantry. You know, white guys.

Yet black soldiers did their part in the campaigns against the Apaches, so I’m off to Sierra Vista. The famous Ninth and 10th Cavalry and 24th and 25th Infantry Buffalo Soldiers were active against the Apaches, although the soldiers were stationed primarily in New Mexico and West Texas. Not until the 1890s did the Ninth Cavalry come to Fort Huachuca, and the fort, still an active post, has been considered the home of the Buffalo Soldiers since 1913.

Established by the Sixth Cavalry in 1877, Fort Huachuca became one of the main military establishments during the Apache campaigns, and the Fort Huachuca Historical Museum excellently depicts military life during those times. Not only will you learn about soldiers both black and white, but you’ll also learn about the honorable roles and efforts of the U.S. Indian Scouts.

The fort most associated with the Apache Wars, though, is isolated Fort Bowie. Put on your hiking shoes and watch out for rattlers, because it’s a three-mile, round-trip walk to this national historic site.

In many ways, the Apache Wars are book-ended by Fort Bowie and the surrounding area. Walking along the trail to the fort’s adobe walls, I pass the remains of the Overland Mail Company station, a replica Apache wickiup, the post cemetery and Apache Springs. This is the country that saw the Bascom Affair in 1861, which led to Cochise’s long-running war. Here was fought the Battle of Apache Pass in 1862. And the fort was a major post that forced Geronimo finally to surrender.

“Now you’ve walked the same trails that Geronimo took more than a hundred years ago,” a bored park ranger tells me when I reach the visitors center.

New Mexico’s Stories

Stories of the Apache campaigns are also told in New Mexico at Fort Bayard just outside of Silver City and at Fort Selden State Historic Park near Las Cruces. Fort museums typically tell more history from the military perspective, but there are two sides to the Apache Wars.

Look at the land and you understand the Apache. In Arizona, I take time to camp at Chiricahua National Monument and bounce my way to the remote campground and hiking trails of Cochise Stronghold, breathing a sigh of relief that all five stream-bed crossings on Forest Road 84 are dry.

Located in Coronado National Forest, Cochise Stronghold, a natural fortress in the Dragoon Mountains, served as Cochise’s home for approximately 15 years. It’s still pretty much a fortress, remote and rugged. Cochise’s war ended in 1872 after Tom Jeffords negotiated a truce. After Cochise died in 1874, he was buried somewhere among these rocks.

Geronimo!

Then there’s Geronimo. Born in the late 1820s and given the Apache name Goyathlay, Geronimo is probably the most recognized leader of Apache resistance. His Apache name means “One Who Yawns,” but I’ve seen photographs of Geronimo and I’ve met Wes Studi (who played the Apache leader in director Walter Hill’s 1993 biopic), and they never yawn. Cut your heart out and eat it, yes. Yawn? I think not.

Geronimo and the Apache lifestyle are well chronicled at the Geronimo Springs Museum in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. For years I thought this was just a silly town off I-25 that named itself after a silly TV show. Yet Truth or Consequences is more than that, and after hiking across the Dragoons and Chiricahuas of Arizona and the Gila Wilderness of New Mexico, you’ll want a nice soak in some Hot Springs, which was the name of this burg before it became Truth or Consequences.

At the museum, I find Geronimo—a life-size wax figure—and paintings by the incomparable Delmas Howe. The Apache Room documents Geronimo’s life, but the museum also provides information on other Apache figures, including Victorio, Nana and Lozen.

The Apache Wars ended with the surrender of Geronimo, and the Apaches were imprisoned—along with the Apache scouts who helped end the bloodshed—in Florida and Alabama, where many died. Children were eventually shipped to the Indian boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In time, Geronimo and some of his fellow Apaches were sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, still prisoners of war.

It’s a long, hot drive from southern New Mexico to Oklahoma but well worth it.

Oklahoma Connections

Before I get to Lawton, I stop off at Anadarko, home to Indian City U.S.A., the Southern Plains Indian Museum and the National Hall of Fame for Famous American Indians. Geronimo’s there. He’s buried at Fort Sill.

Fort Sill is also an active military post, but it houses not only a first-rate museum, established in 1934, but also a who’s who of Indian graves. In the post cemetery, you’ll find names like Quanah Parker, Kicking Bird, Satanta and Satank, but after paying your respects there, keep driving deeper into the fort to the Apache cemetery.

Geronimo’s grave is decorated with the gifts of many visitors through the years, from dream catchers to coins. The last leader of Apache resistance died of pneumonia on February 17, 1909, hundreds of miles from his homeland, still a POW. Standing here alone, I can almost hear his voice in the wind.

“I cannot think that we are useless, or God would not have created us. There is one God looking down on us all. We are all the children of one God. The sun, the darkness, the winds are all listening to what we have to say.”