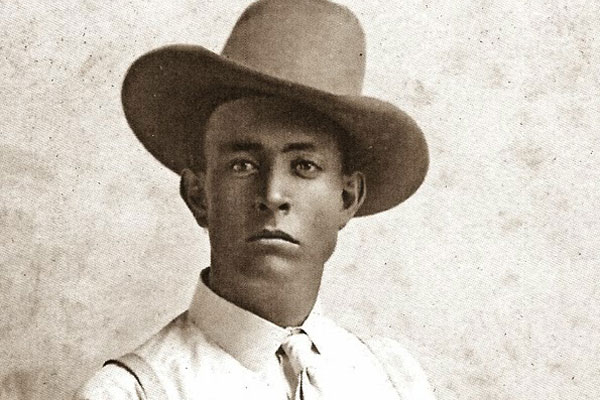

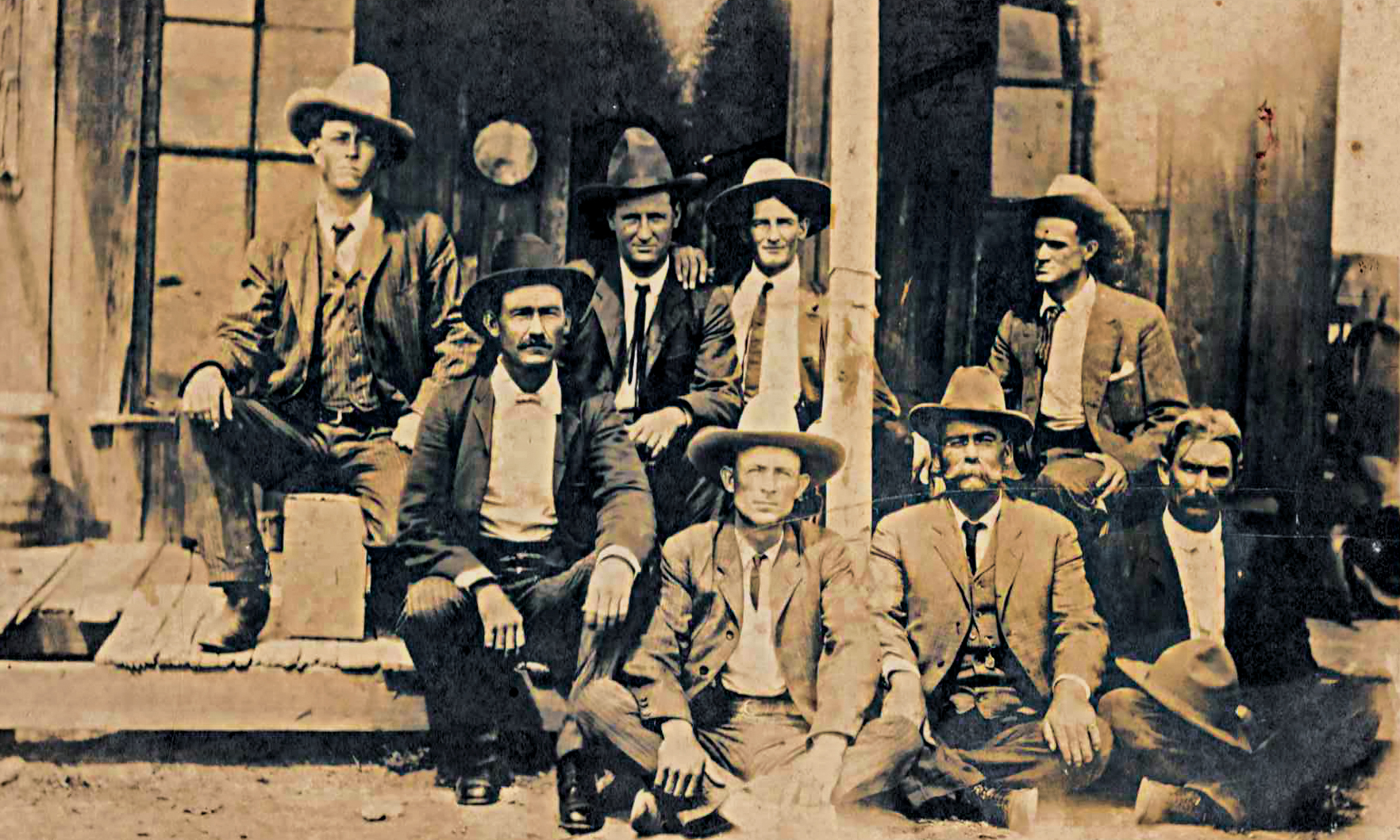

— Courtesy John Boessenecker —

Frank Hamer’s career began during the closing years of the Texas frontier, and saw him transition from a horseback Ranger into a motorized gangbuster of the 1930s. In between, he served decades as a lawman, in and out of the Texas Rangers: city marshal of the rowdy east Texas town of Navasota, special officer in Houston, deputy sheriff of Kimble County, U.S. prohibition officer and Texas Ranger captain. Among his countless exploits, he played a prominent role in the so‑called Bandit War of 1915, when Mexican revolutionaries surged across the border and raided in south Texas. In 1917 he got mixed up in the Johnson‑Sims feud, killing one man in the feud’s climactic gunfight in Sweetwater. Hamer’s role in a violent vendetta was certainly the low point in his professional life. In 1921, as a Texas Ranger captain, he and his men crossed the Mexican border and ambushed and killed the gang of Rafael Lopez, who had murdered five lawmen in Utah’s worst law enforcement tragedy. Captain Hamer then led the Rangers who tamed the oil boomtowns of Mexia and Borger, and investigated—and solved— some of the most sensational Texas murders of the 1920s.

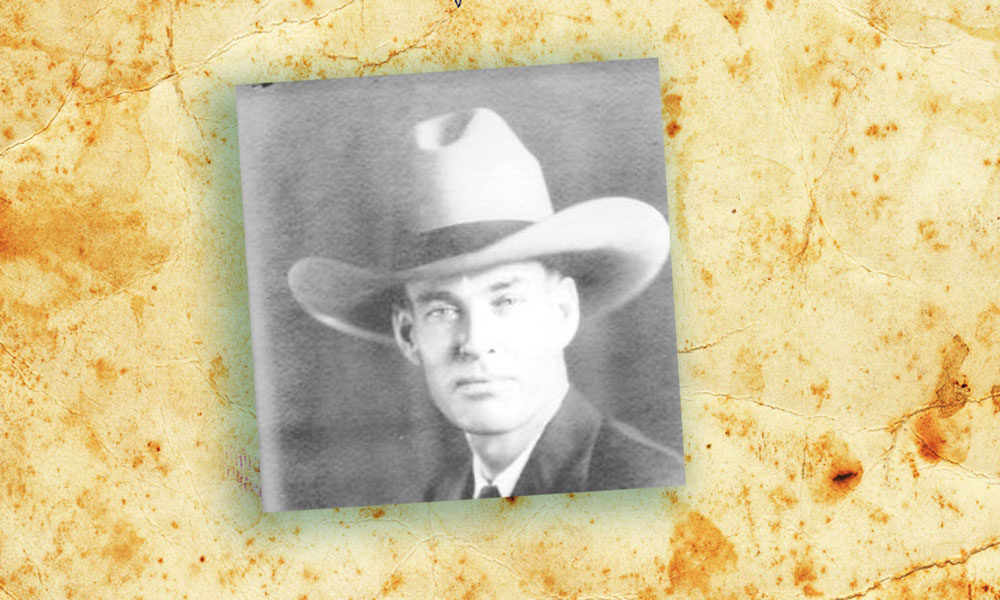

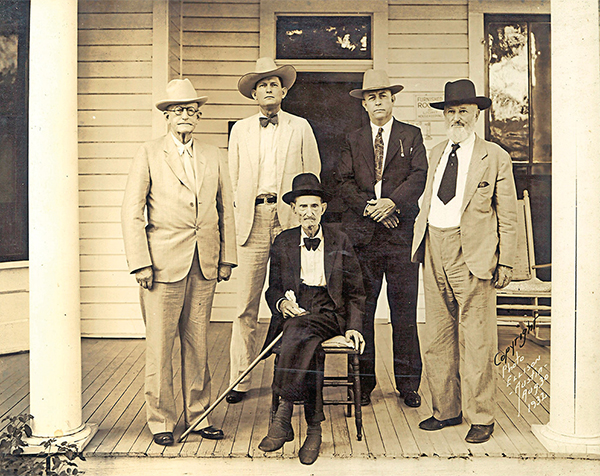

— Courtesy of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas —

Although a white supremacist of the Jim Crow era, Hamer was sympathetic to black Americans. Beginning in 1908, he saved 15 black men from certain death at the hands of lynch mobs in various towns and cities in east Texas. During the Roaring Twenties, Hamer led an unpopular fight against the Ku Klux Klan in Texas. In 1930, at the courthouse in Sherman in north Texas, Hamer and three of his Rangers held off a mob of 6,000 intent on lynching a black man who had raped a white woman. When the rioters burned down their own courthouse in order to kill the prisoner locked up inside, Frank Hamer became the first and only Texas Ranger to lose a prisoner to a lynch mob. He and his men barely escaped the raging inferno alive. Nonetheless, Hamer’s stubborn refusal to back down against massive odds, and his shooting of two of the Sherman mob leaders, constitute one of the greatest displays of raw courage in the history of American law enforcement.

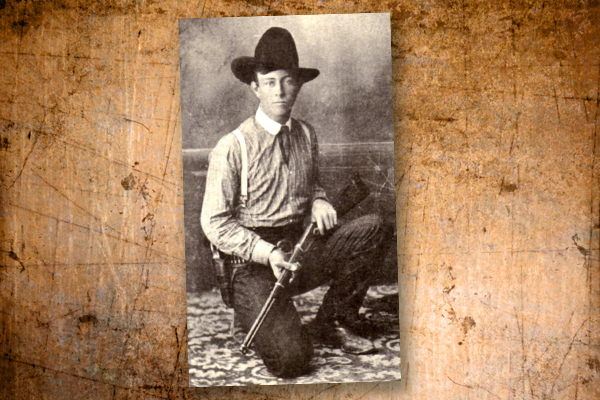

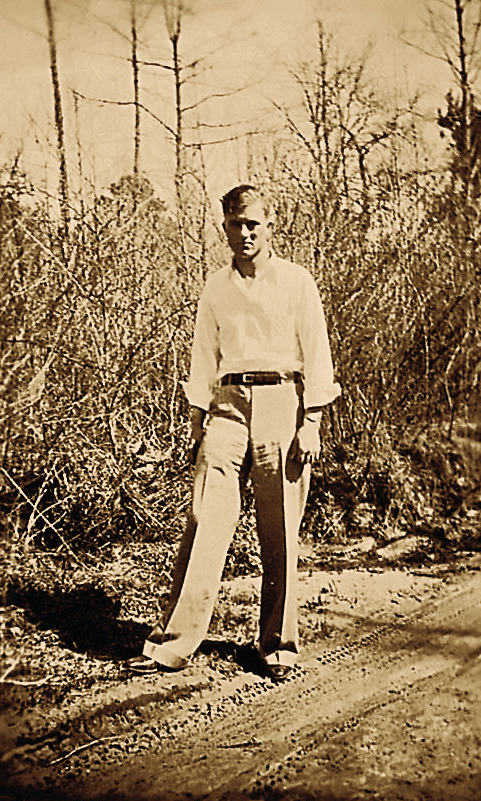

— Courtesy Travis Hamer Collection —

But to many people in Jim Crow‑era Texas, saving the lives of black suspects really did not matter. Hamer’s actions in Sherman were quickly forgotten. What the public did remember was a much more famous—and by comparison, a much less important—exploit. That was Hamer’s 1934 manhunt for Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. The true story of his manhunt was long muddied by myth, misinformation and unreliable reminiscences from old-timers. Then, in 2006, the voluminous FBI file on Bonnie and Clyde was discovered in Dallas and declassified in 2009. The special agents’ reports described in detail the twists and turns in the Barrow manhunt, and made obsolete much of what had been written before about Frank Hamer’s leading role in tracking down the love‑struck outlaw duo.

Clyde Barrow was a career criminal who came from a family of criminals: of seven Barrow children, five were convicted felons. According to myth, he was forced by the Depression into a life of crime, but in fact Clyde became a 13‑year‑old chicken thief in 1922, seven years before the Depression even hit Texas. He certainly led Bonnie Parker into a career of crime, but she followed willingly. In myth, she was an innocent girl who never fired a gun. In fact, during a bank holdup in Lucerne, Indiana, Bonnie fired at unarmed citizens. Following a bank robbery in Okabena, Minnesota, Bonnie, Clyde and his brother, Buck Barrow fired at citizens with shotguns and Browning automatic rifles, narrowly missing a school bus full of children. Bonnie shot at lawmen in gunfights at Joplin, Missouri, and Dexter, Iowa. She was, in the popular term of that era, a gun moll.

Former Texas Ranger Hamer joined the manhunt for Bonnie and Clyde on February 10, 1934. By that time the Barrow gang had pulled countless holdups throughout the Southwest and Midwest and murdered nine men—six of them law officers. Despite the fact that he was the best manhunter in Texas, Hamer was then unemployed. A year earlier, the new Texas governor, Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, had fired the entire Ranger force, Hamer among them (Hamer had placed himself on indefinite leave since November), for politicking against her. Then, in January 1934, Bonnie and Clyde engineered a bloody break from the Eastham Prison Farm, killing one guard and freeing several of their gang. Hamer was appointed a special investigator for the Texas Prison System with orders to track down Bonnie and Clyde.

According to legend, Hamer hunted them alone, living and sleeping in his car. That is hardly what happened. A consummate professional, Frank immediately teamed up with Bob Alcorn, a veteran Dallas deputy sheriff who knew Clyde Barrow and had once arrested him. Hamer suspected that Henry Methvin, who had escaped in the Eastham prison break, was riding with the gang. He also knew that Methvin hailed from northwestern Louisiana. Hamer and Alcorn drove to Shreveport where they met quietly with local officers and asked them to be on the lookout for Bonnie and Clyde. Then, on February 19, 1934, they drove west to Arcadia where they met with Henderson Jordan, the rookie sheriff of Bienville Parish, and asked him to watch for the two fugitives.

On February 23, Hamer and Alcorn returned to Texas, and two weeks later Frank visited Huntsville Prison, where he interviewed Hilton Bybee, one of the gang members who had recently been captured. Bybee, who had refused to talk with other officers, made a full confession to Hamer about the gang’s movements. Bybee confirmed that Henry Methvin was still riding with Bonnie and Clyde. Hamer recognized that Methvin might well be the key to locating Bonnie and Clyde. Because Bob Alcorn was then tied up investigating an unrelated bank holdup, Hamer met with the FBI’s special agent in charge of the Dallas office, who assigned agent Edward J. Dowd to work with him. In early March the two officers traveled throughout north Texas, interviewing witnesses and recovering a Ford sedan that Clyde had stolen in Arkansas.

— Photos Courtesy True West Archives —

FBI agents, acting on Hamer’s information, began trying to locate Henry Methvin’s family in Louisiana. They met with Sheriff Henderson Jordan, told him that Methvin was riding with Bonnie and Clyde, and asked him to try to find Ivan “Ivy” Methvin, Henry’s father, whom they believed had recently settled in Bienville Parish. The Methvins were dirt poor and moved frequently, sometimes squatting in isolated cabins and farmhouses. Sheriff Jordan spent the next ten days snooping around the southwestern part of his parish, quietly searching for Ivan Methvin. He finally heard a rumor that Ivy Methvin and his family had been living near Ashland in Natchitoches Parish.

Meanwhile, on Easter Sunday, April 1, Bonnie and Clyde murdered two Texas highway patrolmen north of Dallas. They fled with Henry Methvin to Oklahoma, where five days later they killed a local constable. Clyde, driving by night at high speed in stolen autos, managed to evade a massive, multi-state dragnet. Soon after this, John Joyner, a friend of Ivy Methvin, contacted Sheriff Jordan and asked for a secret meeting with the elder Methvin. Jordan and his chief deputy, Prentiss Oakley, did so, and Methvin offered to give up Bonnie and Clyde in exchange for a Texas pardon for his son. Sheriff Jordan then contacted Louisiana FBI agent Leslie Kindell about the offer. The federal government had no authority to offer a Texas pardon, but Agent Kindell knew that Frank Hamer did. When Kindell, Hamer and Jordan met in Shreveport, Sheriff Jordan recalled, “Hamer agreed that a deal could be offered to the Methvin family. If Ivy Methvin would help capture Bonnie and Clyde, consideration would be given to Henry Methvin. While Hamer did not promise that all charges against Methvin would be dropped by the state of Texas, he came real close to saying that. Before the meeting was over, I came to realize that was the offer that I was to make to Methvin. If he would help capture Bonnie and Clyde, Henry would not have to go back to prison.”

— Courtesy Taronda Schulz Collection —

On April 28, 1934, Hamer, with Alcorn, Agent Kindell and Sheriff Jordan, met secretly in the woods with Ivy Methvin, his wife, two of his sons and his brother. Hamer produced an official letter promising a pardon for Henry Methvin if his family cooperated. The Methvins talked over the offer at great length and finally agreed to accept it. Ivy explained that “no one knows just when Barrow is coming in and he remains only a very few hours and usually does not get out of his automobile.”

The lawmen had several more meetings with the Methvins. Finally, on the night of May 22, 1934, they got word that Bonnie and Clyde would visit the Methvin house, located near the little crossroads of Sailes, the next morning. Hamer and his men set up an ambush on the highway between Gibsland and Sailes, and waited through the dark morning hours. At nine a.m. Bonnie and Clyde drove up. Within moments their stolen Ford sedan was riddled with 167 bullets and buckshot, and the two lovers passed into outlaw immortality.

John Boessenecker is True West’s 2011, 2013 and 2019 Best Nonfiction Writer of the Year. His most recent book is Shotguns and Stagecoaches: The Brave Men who Rode for Wells Fargo in the Wild West. He adapted “Frank Hamer vs. Bonnie and Clyde” from his New York Times bestseller Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, The Man who Killed Bonnie and Clyde.