Graham Greene’s storied 45-year career in film and television has left a trail of excellence.

One of the most recent of Graham Greene’s 150-plus screen characterizations is in INSP’s movie Blue Ridge, a contemporary Western about Appalachian backwoods clans, with a “Hatfields and McCoys” feel. The Native Canadian actor explains that his character was “the patriarch of his family, and he ran everything with an iron fist. He hated the other family, blamed them for killing his daughter.” Greene is happy to see the movie released. “I did a bunch of films that haven’t been released yet because of COVID-19 that’s going around.”

– Courtesy Orion Pictures –

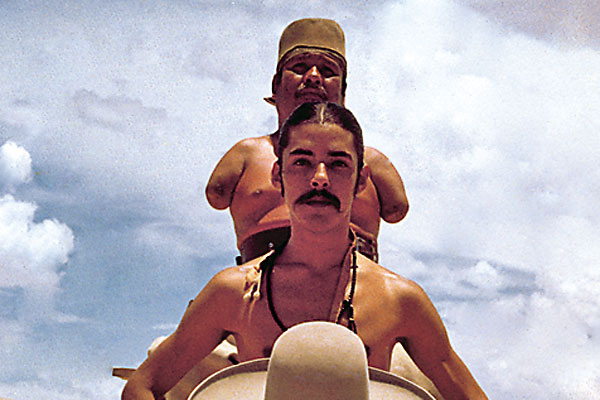

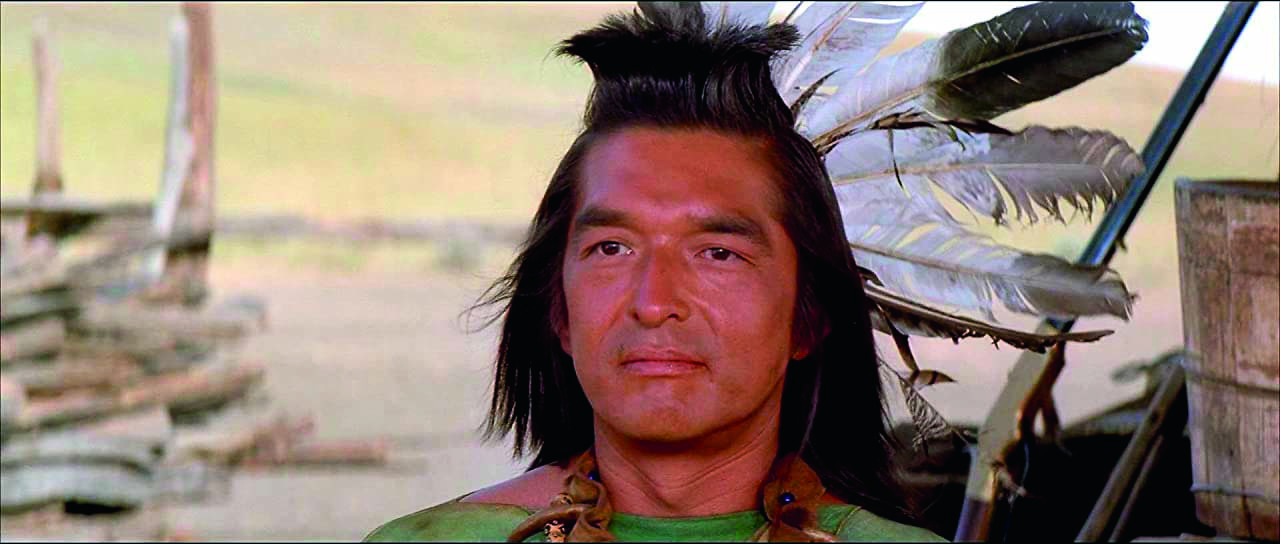

For over a decade, Greene was a busy actor on Canadian television, and in supporting roles in small features, until 1990’s Dances with Wolves made him not just a familiar face, but a star. He earned an Oscar nomination for playing Kicking Bird, a performance in an English-language film, but not in English. “It took three months to learn the dialogue. I had no idea what I was saying,” Greene recalls, “and I had to learn it phonetically. I’d be running 10 miles a day with my headphones on, listening to the translations, mumbling away in Lakota, and people were looking at me funny. But I got it down.”

It was a tremendous undertaking for first-time director Kevin Costner. “He did fine,” Greene says. “We stayed out of his way and let him make his decisions. I only questioned him once, [when Kicking Bird] was going nuts looking for a peace pipe. I said, ‘He’s a medicine person. He would never lose a peace pipe. Why do you want me to do that?’ He said, ‘Because it looks good.’ I said, ‘Good enough.’”

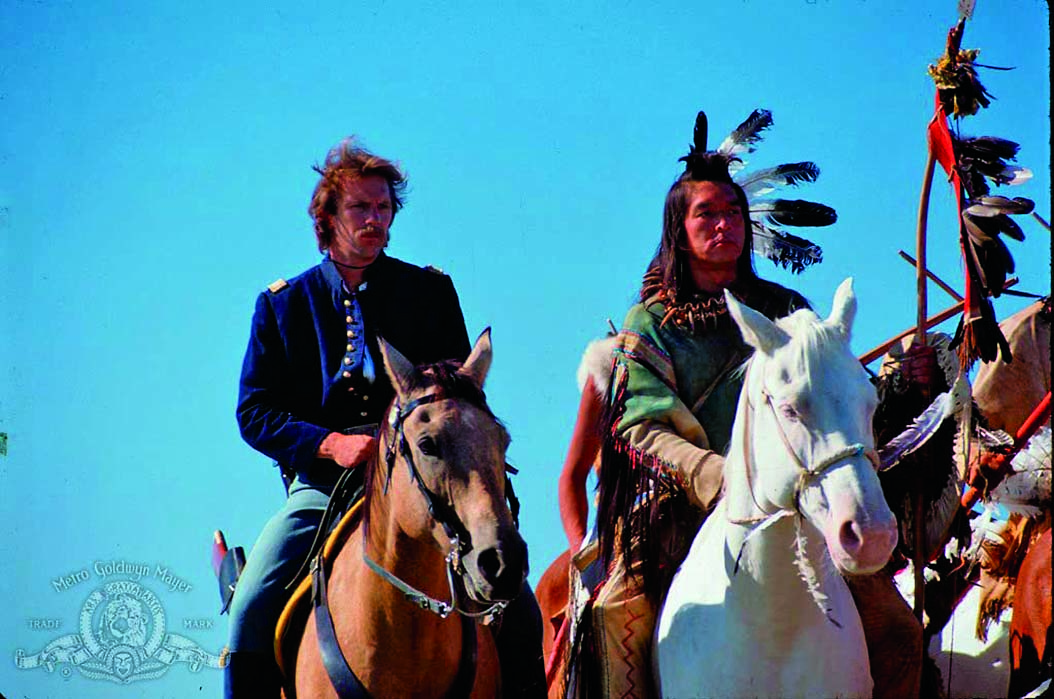

Two years later Greene starred with Val Kilmer and Sam Shepherd in the groundbreaking Thunderheart, which defined the feel of contemporary ‘Res’ (reservation) Westerns like Longmire, Yellowstone and the Tony Hillerman/Joe Leaphorn films. It wasn’t hard to convince Greene to do it. “I love The Badlands. My agent said, ‘I got a film for you. It’s in South Dakota. And you have to ride a motorcycle.’ I said, ‘I’m in.’ ‘Want to read it?’ ‘Don’t have to.’ Val was a strange fellow to work with. I just couldn’t get into his head, what he was thinking, what he was doing. He was very to himself.”

– Courtesy Warner Horizon Television–

Greene’s character, Walter Crowhorse, had one foot in the spirit world and one in the physical realm. “Crowhorse was fun because John Fusco wrote a great part. [Director] Michael [Apted] was great to work with. He just dropped the reins and let the actors go.”

– Courtesy TriStar Pictures –

While he’s done several period Westerns, Greene has done many more contemporary roles. “I like working in modern times. Doing period films is a lot of work. It’s hard on the crew, the cast, everybody. I guess my favorite one was doing Molly’s Game, playing the judge. Aaron [Sorkin], the director, was looking at me sitting behind the bench. I had a puzzled look on my face. He said, ‘Are you all right?’ I said, ‘Yeah. I’ve just never seen the bench from this side before.’”

– Courtesy INSP Films –

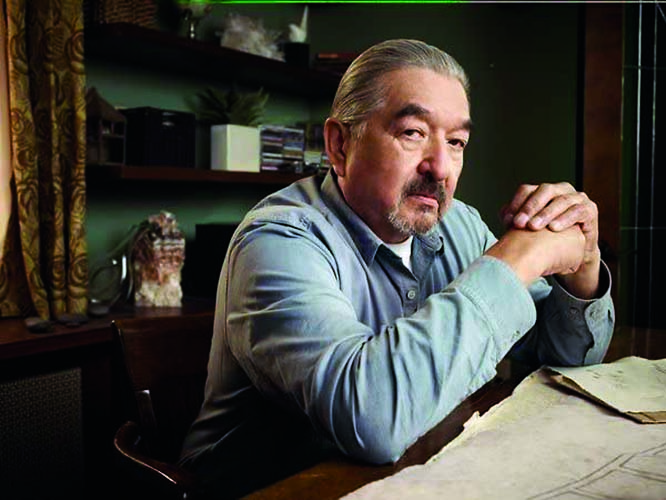

After a long career of playing good guys, he got to go to the dark side, playing the evil Malachi on Longmire. “Yeah, I had fun playing that. They wrote that because Lou Diamond [Phillips] kept bugging them. ‘You’ve got to get Graham Greene on the show.’ So they wrote the part of Malachi. I read it and went, ‘Oh boy, that’s perfect.’ After the second season, they let me just go and do what I wanted because I knew the character so well. Like when I did Goliath, playing a nasty casino owner,” opposite Billy Bob Thornton. “It was fun. It said I turned into a crow at night and watched people. I adapted these gestures; tilted my head looking at people, making a clucking noise. Playing villains is fun. Being nice all the time; it’s boring.”

– Courtesy Acacia Filmed Entertainment –

Another of Greene’s favorite roles was in the series Defiance, in which he and director Michael Nankin talked in a sort of shorthand, he says, “because we knew all these old films the kids had never seen. ‘Do you want me to do a Bogart in this?’ ‘Yeah, that would be great.’ And they go, ‘What’s a Bogart?’ ‘‘When you slowly turn around, look at somebody, and snarl at them.’ One of the things that I really want to do, now that I am getting older and fading fast, is teach kids what to do in front of the camera. Because a lot of them don’t know. They’ll stare at the ground and mumble. I said, ‘No, the camera’s going to be over my left shoulder, look at my left eye; talk to me, not the ground.’ I advise them to spend two or three years doing theater, because you’ve got to learn discipline, or you won’t last very long. They ask, ‘How did you last this long, Mr. Greene, 40-some years?’ And I say, ‘I’ve got a thick skin and a hard head.’”

– Courtesy Syfy TV –

BLU-RAY REVIEW

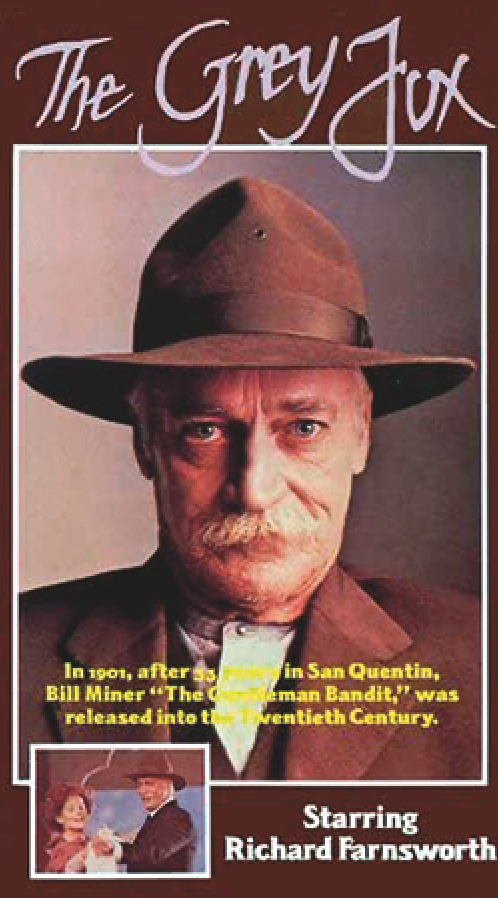

The Grey Fox (1982)

(Kino Lorber – Blu-Ray $29.95, DVD $19.95) In 1901, after 33 years in San Quentin, Old West stagecoach robber Bill Miner is released into a world he scarcely recognizes. Alone and adrift, he happens into a nickelodeon and sees a movie that gives him hope, and a new career: The Great Train Robbery. Richard Farnsworth, who spent decades stunting in movies before becoming a twice-Oscar-nominated actor, is irresistible as the senior train robber, with his gentle blue eyes and steel spine. With Miner’s humility, and pride in his professionalism, he’s hard not to admire, although his folly is obvious. First-time director Philip Borsos elegantly balances traditional Western elements with Miner’s unexpected romance with a lady photographer (Jackie Burroughs). Canada’s frontier has never been more beautifully photographed than it was by Frank Tidy. A classic!

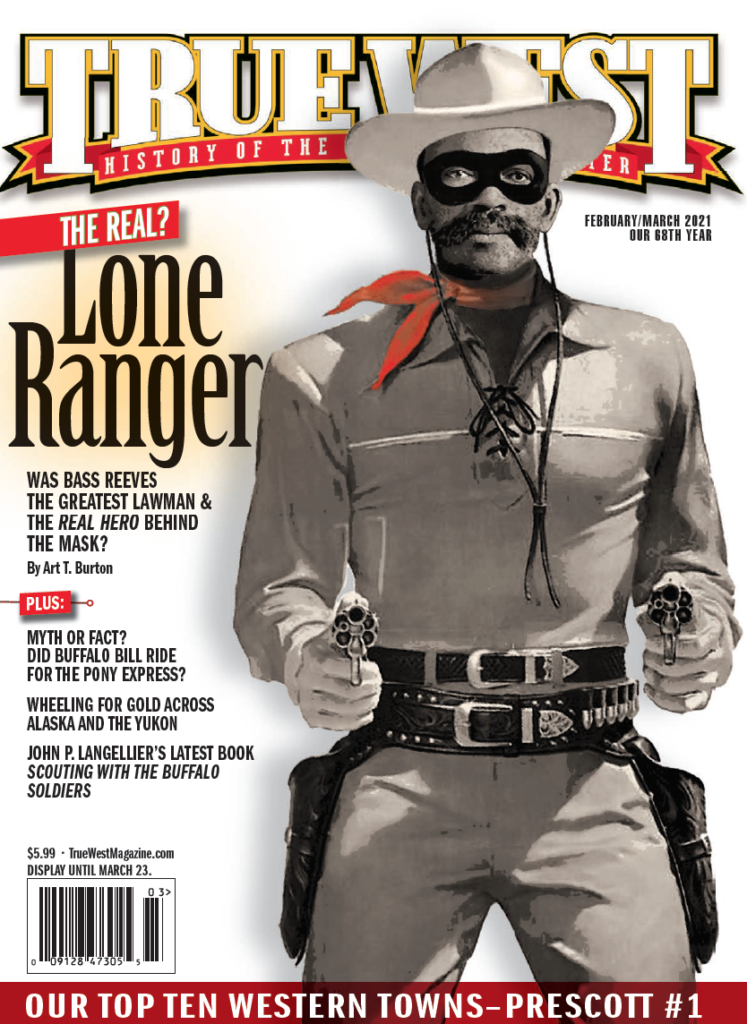

Henry C. Parke, Western Films Editor for

True West, is a screenwriter, and blogs at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year.