When the horse-drawn wagon slipped into a bad rut outside of Taos, New Mexico, in 1898, the two sketching buddies flipped a coin to see who would take the broken wheel to the blacksmith in Taos.

Victory was Bert Phillips’; the defeated Ernest “Blumy” Blumenschein headed off on horseback, hobbled by the wheel he carried.

“My destiny was being decided as I squirmed and cursed while urging the bronco through those many miles of waves of sagebrush,” he later wrote.

When the artist reached the end of his 20-mile journey and entered the village, his entire world changed.

“When I came into this valley—for the first time in my life, I saw whole paintings right before my eyes…. Everywhere I looked I saw paintings perfectly organized, ready for paint,” he wrote.

Thus begun Blumy’s lifetime study of Taos and its people. Fellow artist Joseph Sharp had urged Phillips and Blumy to visit Taos during their sketching trip from Denver, Colorado, to Mexico, an unknown land the artists did not make their way to on that trip. They were so captivated by Taos that they stayed, gripped by a land “green with trees and fields of alfalfa” and populated by friendly Taos Indians “picturesque, colorful, dressed in blankets artistically draped.”

This magical place eventually became the beloved home away from home for artists Joseph Sharp, Ernest Blumenschein, Bert Phillips, E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus and Herbert Dunton. The “Founding Six,” as they were called, formed the Taos Society of Artists in 1915. The group disbanded in 1927, when the artists’ works had made them so famous, they no longer needed the collective of the group to encourage buyers.

Blumy’s paintings, sketches and illustrations scattered across the country have been gathered together for the impressive “In Contemporary Rhythm,” an exhibition tracking Blumy’s artistic life, from his early academic work through his mature works exploring modernism. Its first stop was in New Mexico at the Albuquerque Museum from June 8 to September 7. Next, it appears in Colorado at the DAM, otherwise known as the Denver Art Museum, from November 8 to February 8, 2009. The exhibition closes in Arizona at the Phoenix Art Museum, where it will be featured from March 15 to June 14, 2009.

The University of Oklahoma Press has also released the same-titled book, with the goal of giving “Blumenschein his deserved place in American art,” writes authors Peter H. Hassrick, director of the Institute of Western American Art at the DAM, and Elizabeth J. Cunningham, an authority on Blumenschein. The visual feast is certainly a king’s banquet.

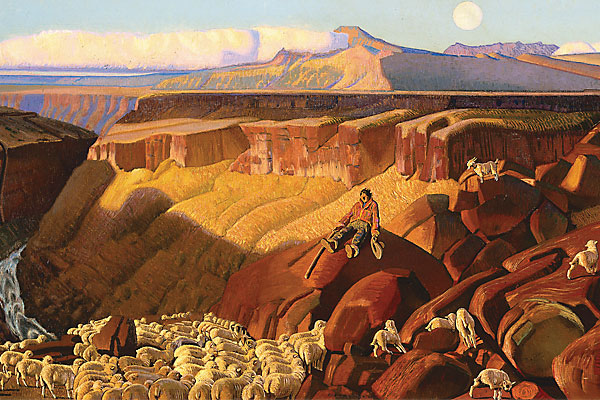

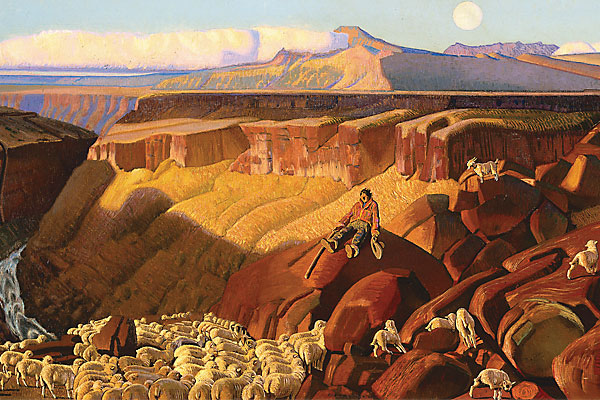

That sagebrush obstacle course the artist had first so terribly encountered became a landscape so dear to his heart. You can just picture him, while reading his words to his friend and Santa Fe Railroad agent William Simpson in 1903: “A wonderful Indian summer is on here with gorgeous color in the mountains and plains. I’m having a very happy time working out of doors with my Indian model on horse-back standing in the sage brush. I’m after the real thing, Indian in his own landscape, painted on the spot.”