– All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted –

Sharpshooter. If that word immediately conjures the image of a man with a gun, think again. History is peppered with female sharpshooters, and a gun wasn’t their only weapon of choice—some used their sharp tongue and wits to hit their marks; some used it all.

Among the most notorious was Pearl Hart, who never even pulled a trigger.

Under five feet and a hundred pounds, this “Lady Bandit” ambushed her way into the history books in 1899: the only known female stagecoach robber pulling off one of the last stagecoach heists in America.

But it was her castrating tongue that captured the attention of the nation and made her a celebrity. Men hated what she had to say; women loved it!

Pearl Hart’s celebrity began about 5 p.m. on May 29, 1899 in Arizona Territory. She was masquerading as a man in a gray shirt and dungarees with her long hair tucked under a dirty white sombrero and her feet in boots that were obviously too big. She and her boyfriend, Joe Boot, laid in wait in Cane Springs Canyon between Florence and Globe, waiting for Henry Bacon’s stage with its three passengers. As she ordered them out of the stage, one of the men left his revolver lying on the seat. Henry never tried to draw the gun he carried.

The press used twisted logic—and erased one of the guns—to explain how four men could be so disarmed by such a slight woman: “They were so pop-eyed with amazement that no resistance was offered, even though the driver was armed.”

Far more cutting was Pearl’s take on the situation: “Really, I can’t see why men carry revolvers, because they almost invariably give them up at the very time they were made to be used.”

She and Joe made off with $431.20; Bacon’s Colt .45; a .44 and a gold watch—minus the $1 “charitable contribution” they left each victim so the guys could pay for supper that night.

But while the robbery was slick, escaping eluded the couple, who got lost and were found just a mile or so from the holdup by Sheriff William C. Truman. They were jailed in Florence, where the sheriff was dismayed to find the men of the press were constant visitors, fascinated by this tiny, pretty 28-year-old bandit who provided such great copy.

Like her letter to prosecutors: “I shall not consent to be tried under a law which my sex had no voice in making.”

Like the mocking poem she wrote to commemorate her crime:

While the birds were sweetly singing, and the men stood up in line,

And the silver softly ringing as it touched this palm of mine;

There we took away their money, but left them enough to eat,

And the men looked so funny as they vaulted to their seats.

Across the nation, women championed this example of “Western womanhood,” with the popular Cosmopolitan magazine printing a massive story on her life and crime. The Arizona Star named her a “woman suffragette,” which may have been only conjecture by the newspaper’s co-owner, Josephine Brawley Hughes, leader of Arizona’s Suffragette Association. Other Arizona papers, campaigning for statehood, which was still 13 years away, bellowed that this kind of adoration for lawlessness wasn’t helping the cause.

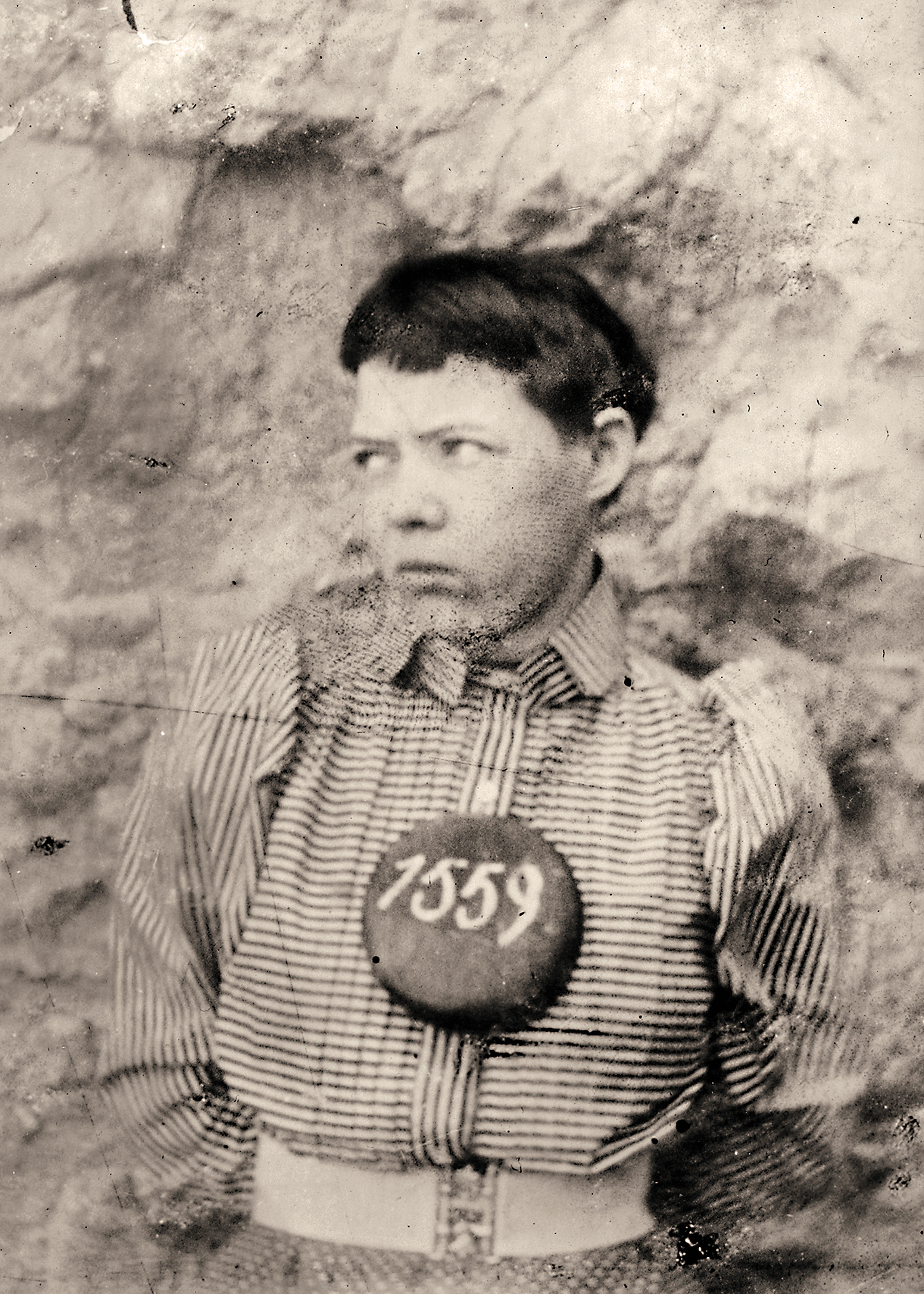

Pearl’s trial brought another black eye for Arizona—her jury voted 11 to 1 to acquit her! Judge Fletcher Doan berated the jury for ignoring Pearl’s confession. She was quickly retried for stealing Henry Bacon’s $10 pistol, and this second jury found her guilty. The judge gave her five years in the Yuma Territorial Prison.

Joe Boot, meanwhile—hardly seen as a darling—was handily convicted of the stage robbery and got a 30-year sentence. The robbers arrived at the Yuma Territorial Prison together, and Pearl put another notch in her celebrity bonnet—she was the only female prisoner.

But, alas, neither of the robbers served their time. Joe simply put on his boots and walked away after serving less than two years and was never heard from again.

On December 15, 1902, Pearl was paroled by Territorial Governor A.O. Brodie, released with a train ticket to St. Louis and, by some accounts, “pockets full of cash.” It took 50 years to find out why, when the late governor’s secretary finally told Arizona historian and newspaper columnist Bert Fireman that they had to get her out of town because she was pregnant. Arizona author Winn Brown reports, “Only three men had been allowed to visit without supervision—and one of them was the governor himself.” If there ever were a baby, there is no record of it.

Pearl eventually returned to Arizona, married a Globe cowboy and lived out her life quietly.

– Courtesy Warner Bros. –

Queen of the West

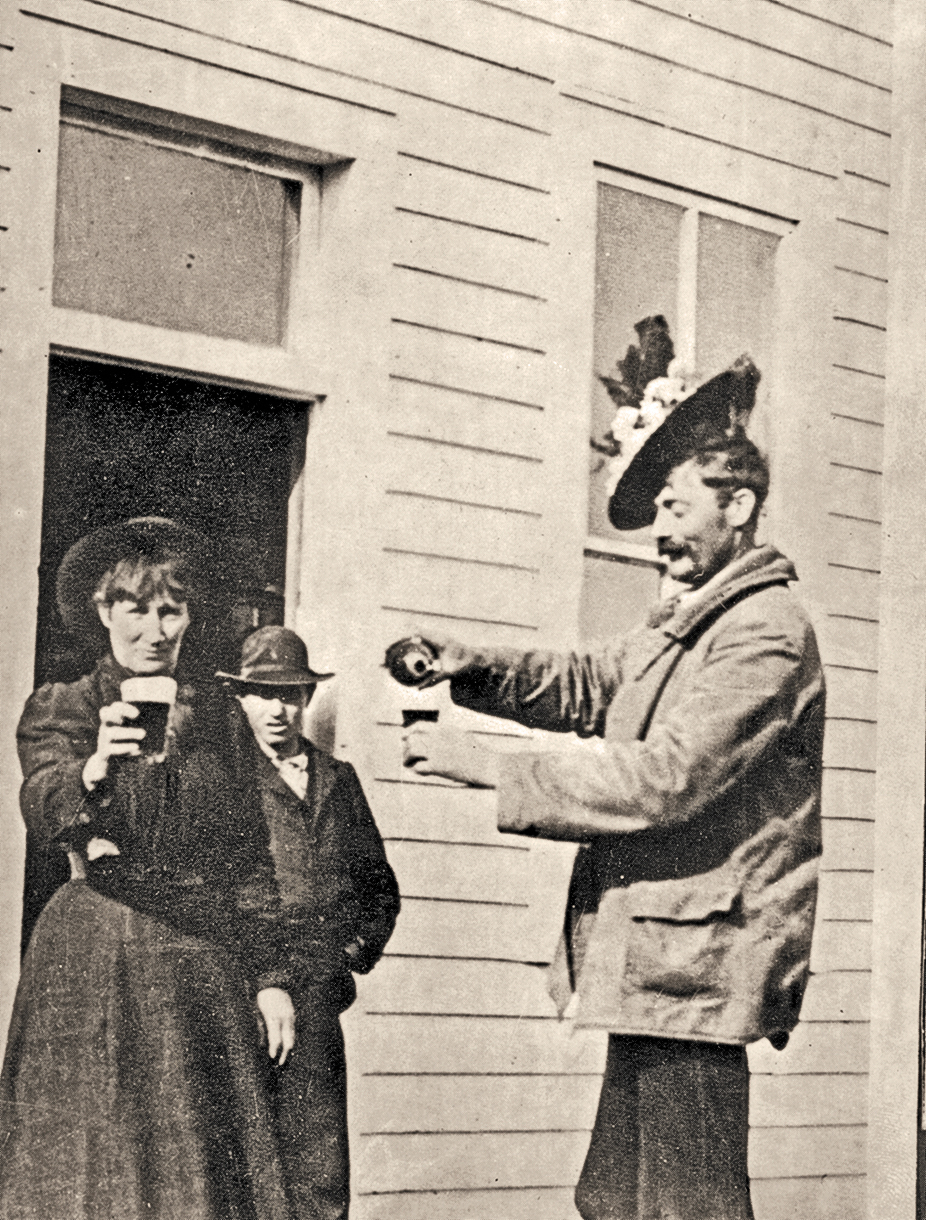

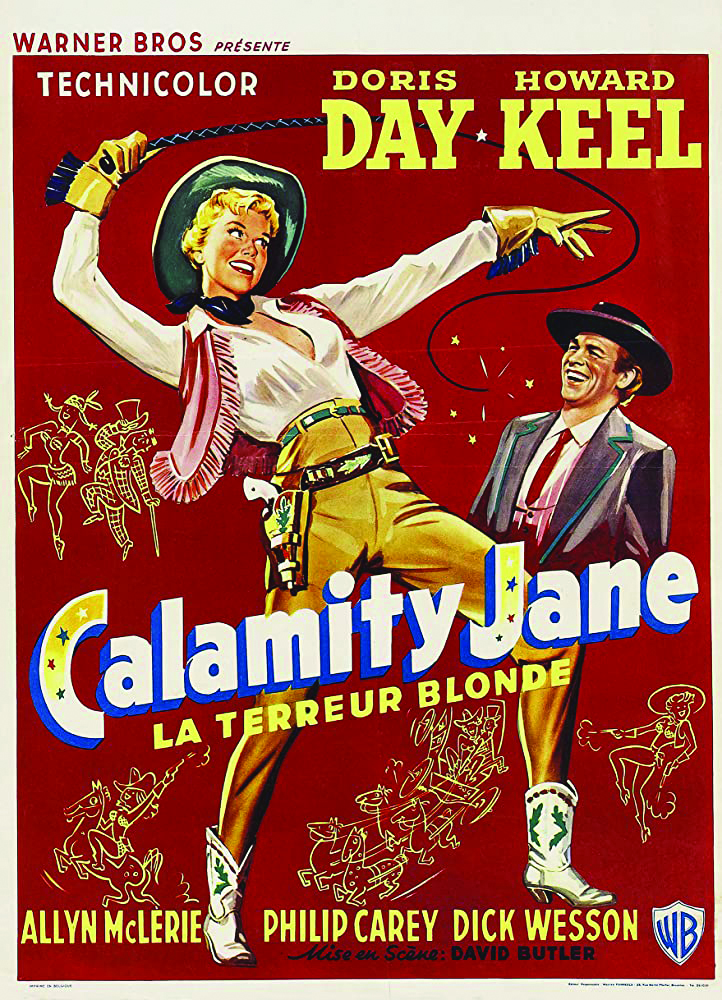

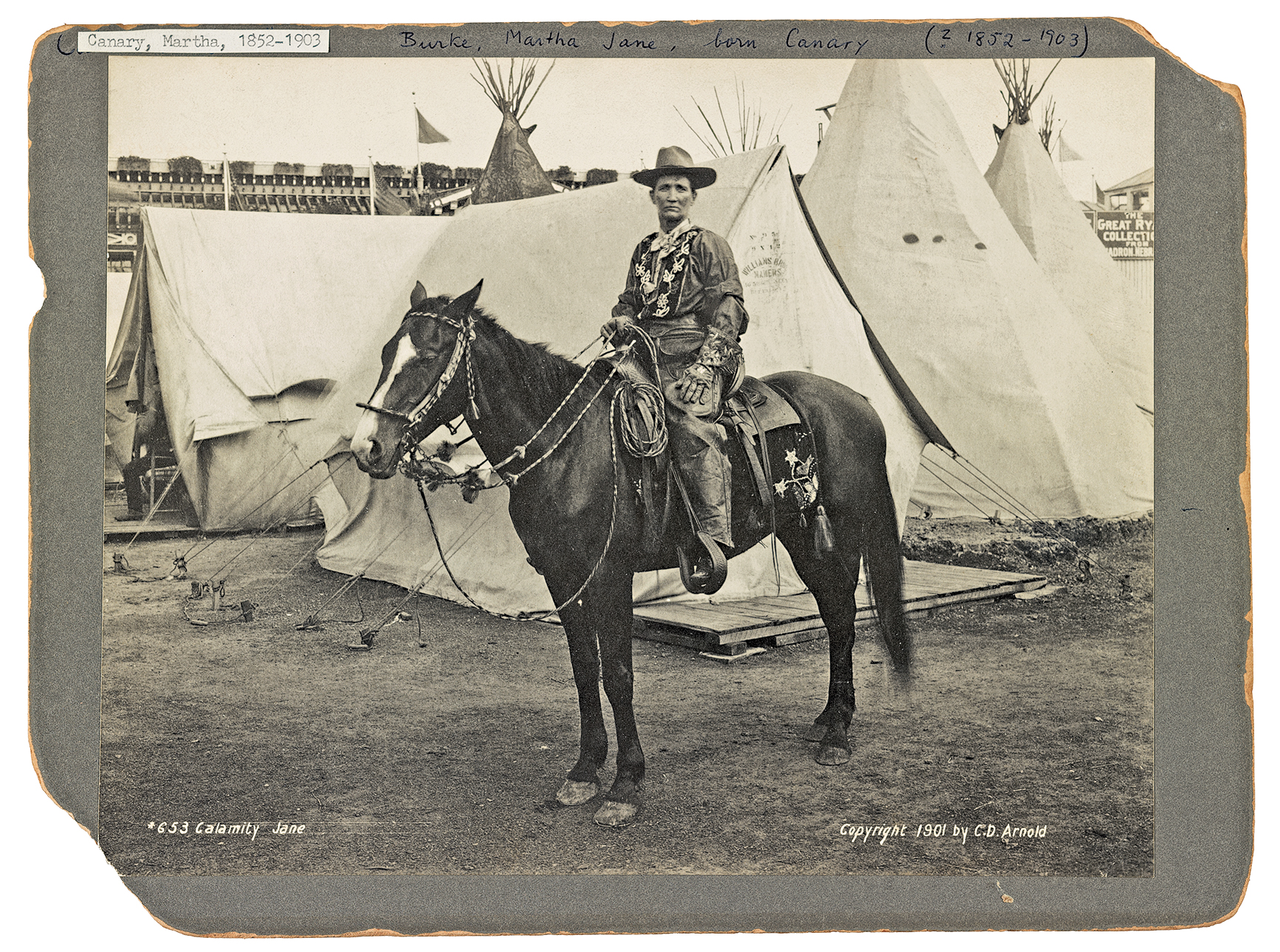

In contrast, Calamity Jane was never quiet. This larger than-life-Western legend—her real name was Martha Canary—perplexed historians, who either wanted to dismiss her as “just a whore” or exalt her as “the West’s Joan of Arc.”

In reality, she was an Army muleskinner and in 1893 joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. But mainly, she was a woman who lived life on her own terms, and most folks were uncomfortable because she preferred buckskin breeches to buckskin dresses.

She famously said, “I figure if a girl wants to be a legend, she should go ahead and be one.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Although portrayed as a notorious ruin, the Deadwood paper gives us a very different look at Calamity Jane in an 1880s article: “She has always been known for her friendliness, generosity and happy cordial manner. It didn’t matter to her whether a person was rich or poor, white or black, or what their circumstances were; Calamity Jane was just the same to all. Her purse was always open to help a hungry fellow.”

She finally got some of her due in the HBO series Deadwood, in which she was one of the few sympathetic characters. The series showed her, correctly, nursing men during a smallpox epidemic. She’s buried in Deadwood, near her beloved Wild Bill Hickok.

Hot Lead and Cold Blood

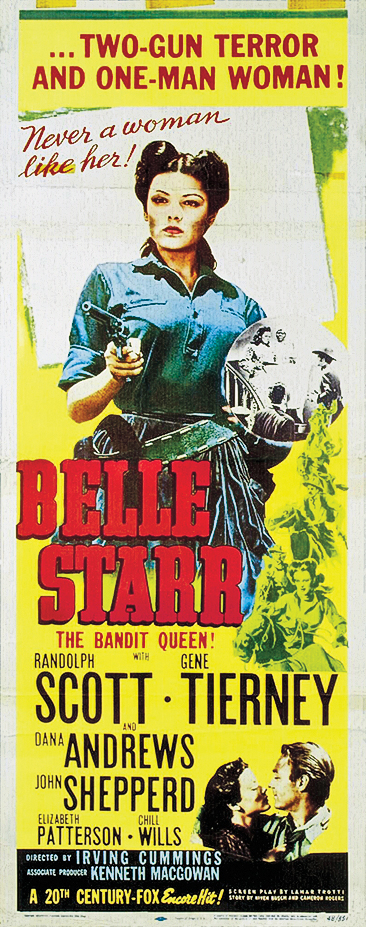

A woman who actually deserved her bad reputation was Belle Starr, labeled the “Bandit Queen.”

She was romanticized as a lovely lady with loose morals and a hot pistol, who ran with the James and Younger gangs. It’s said she cleaned out crooked poker games with her six-shooters and was seen galloping down a main street with her guns blazing.

The most obsessed man in the West over Myra Maybelle Starr was the “hanging judge” Isaac C. Parker. He did get her imprisoned once—for a mere nine months—for horse theft. After her release, she continued her ways, and although she was arrested several times, Judge Parker couldn’t make the charges stick.

“I am a friend to any brave and gallant outlaw,” she’s reported to have said.

Her life ended on February 3, 1889, when she was shot in the back as she rode to her home. She was buried on her ranch in Oklahoma and lies under a marble headstone engraved with this epitaph written by her daughter Pearl:

“Shed not for her the bitter tear,

“Nor give the heart to vain regret;

“‘Tis but the casket that lies here,

“The gem that filled it sparkles yet.”

the Border.

– Courtesy Twentieth

Century Fox –

Dynamite Comes in Small Packages

Two Western women who used the gun most effectively—most spectacularly, most profitably—were both performers for Buffalo Bill’s show.

Everyone knows Annie Oakley, a pint-sized woman who showed an accuracy that made men jealous. They watched her hit 4,772 glass balls out of 5,000 shot into the air. She could hit a playing card from 90 feet, riddling it five times before it hit the ground. That display alone named free tickets with holes punched in them, “Annie Oakley’s.” One of her most popular tricks was splitting a playing card, edge on, from 30 paces. She shot dimes tossed in the air and cigarettes from her husband’s lips.

Born Phoebe Ann Mosey on August 13, 1860, in Ohio, Annie became an international star who performed for royalty.

That doesn’t mean it was easy. While she was acclaimed and adored around the world, she also faced the power of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. In 1904, his papers published a story saying Annie Oakley had been arrested for stealing to support a cocaine habit. It was a false story. The woman actually arrested was a burlesque performer who told Chicago police that her name was Annie Oakley. Obviously, the Hearst papers never double-checked to see if it was the Annie Oakley. But papers across the nation ran the Hearst story, relying on its accuracy.

– Courtesy BBCW_P.69.71–

When they discovered the mistake, most papers printed a retraction and an apology for the libelous story. But Hearst doubled-down, refusing to acknowledge the mistake and instead, he sent investigators to dig up dirt on the real Annie Oakley. He found none.

Annie spent the next six years winning 54 of 55 libel lawsuits against newspapers—paying far more in legal fees than she won in judgments, but that didn’t matter. What mattered to her was restoring her reputation.

She did, and then built on it. She was 62 on March 5, 1922, when she broke all existing records for women’s trap shooting. She smashed 98 out of 100 clay targets.

She died four years later and remains to this day a favorite Western icon.

– Courtesy RKO –

Sharpshooter Extraordinaire

The other female trick shooter is nowhere near as famous, even though she was as good a shot as Annie—some say even better, as Lillian Smith’s biographer Julia Bricklin titled the book America’s Best Female Sharpshooter.

The women were rivals, with a dignified Annie objecting to the more flamboyant Lillian. Tiny Annie sneered at Lillian’s “ample figure” and chided her poor grammar. While Lillian boldly declared that “Oakley was done for” once her own skills were revealed.

The brag wasn’t empty. Lillian could shoot her rifle from her right shoulder, her left shoulder, upside down and backward, over her shoulder or sighted with a hand mirror. She hardly ever missed.

Lillian was just 14 in 1885 when she showed off her skills at a San Francisco exhibition. Using a Winchester, she burst 100 glass balls in two minutes, 35 seconds—one second faster than the record held by William Frank “Doc” Carver.

Buffalo Bill was so sure of her marksmanship, he offered a purse of $10,000 to anyone who could out-shoot her—the equivalent of $266,000 today.

It appears that Annie convinced Buffalo Bill to fire Lillian, who vanished for a time into obscurity. Then around 1900, she reappeared, remade as a Sioux princess named Wenona. She performed in other Wild West shows—Pawnee Bill’s, Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West—but her glory days were over, although till the very end, she could still shoot like hell.

The Mother of Wyoming Suffrage

Perhaps the greatest Western female sharpshooter of all is a woman who never picked up a gun but used her sharp mind and sharp tongue to start a movement that would eventually arouse the entire nation. Esther Hobart Slack Morris is known as the “mother of woman suffrage in Wyoming.” It was a title bestowed on her by her newspaper editor son, Ed Slack.

History says that in 1869, she invited influential Democrats and Republicans to her Cheyenne home for a “tea party” and wouldn’t let them depart until they pledged to vote for female suffrage. Some historians doubt that story, but most think the proof is in the pudding, for in 1869, Wyoming Territory became the first to give women the vote. That was 51 years before the 19th Amendment extended the vote to women.

– Photo of Sweetwater Jail Courtesy Library of Congress/Newspapers.com –

And where Wyoming went, the rest of the West followed. By the time the Susan B. Anthony Amendment became law, every Western state except New Mexico had granted women full voting rights—the envy of suffragettes everywhere else.

P.S. In 1870, Esther became the first woman in the nation to hold public office when she was appointed a justice in South Pass City, Wyoming.

She was obviously a force to be reckoned with, as were all the women who dared speak up, stand up or shoot up. Sharpshooters, all!

Jana Bommersbach is an acclaimed Arizona journalist and longtime writer for True West magazine, who has specialized in women of the Old West. This year she is being inducted into the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame.