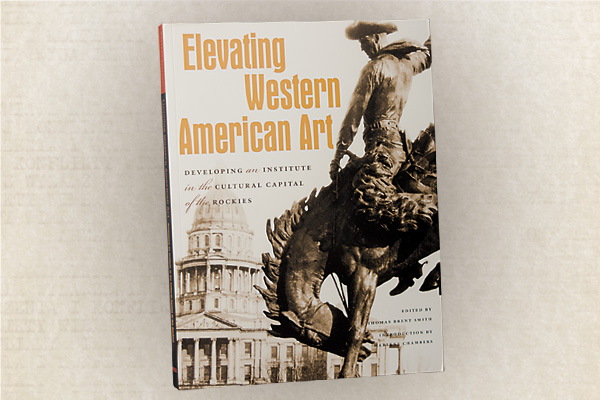

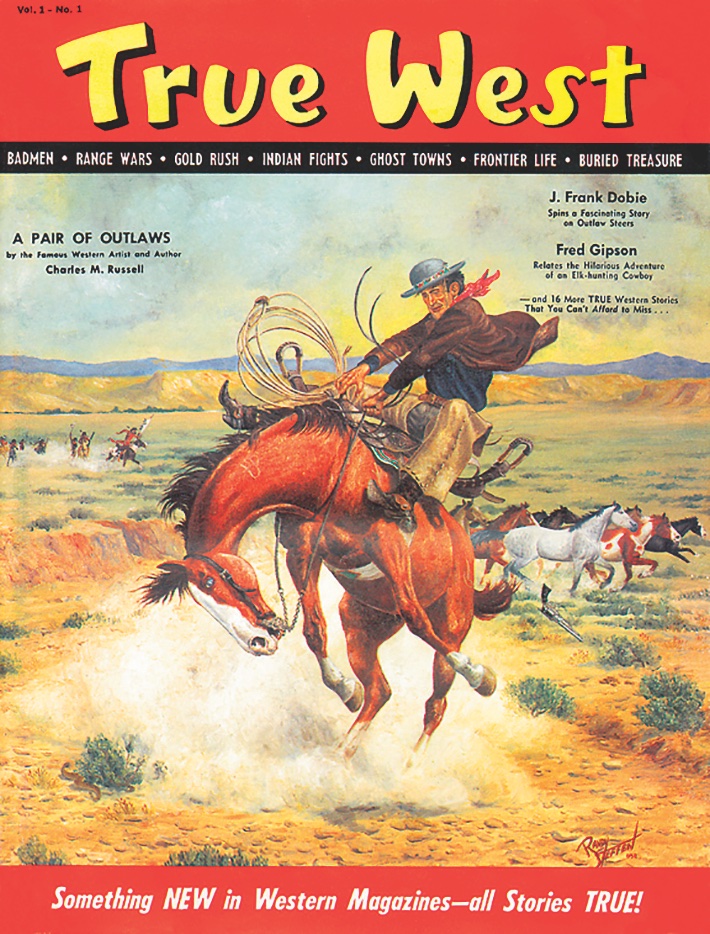

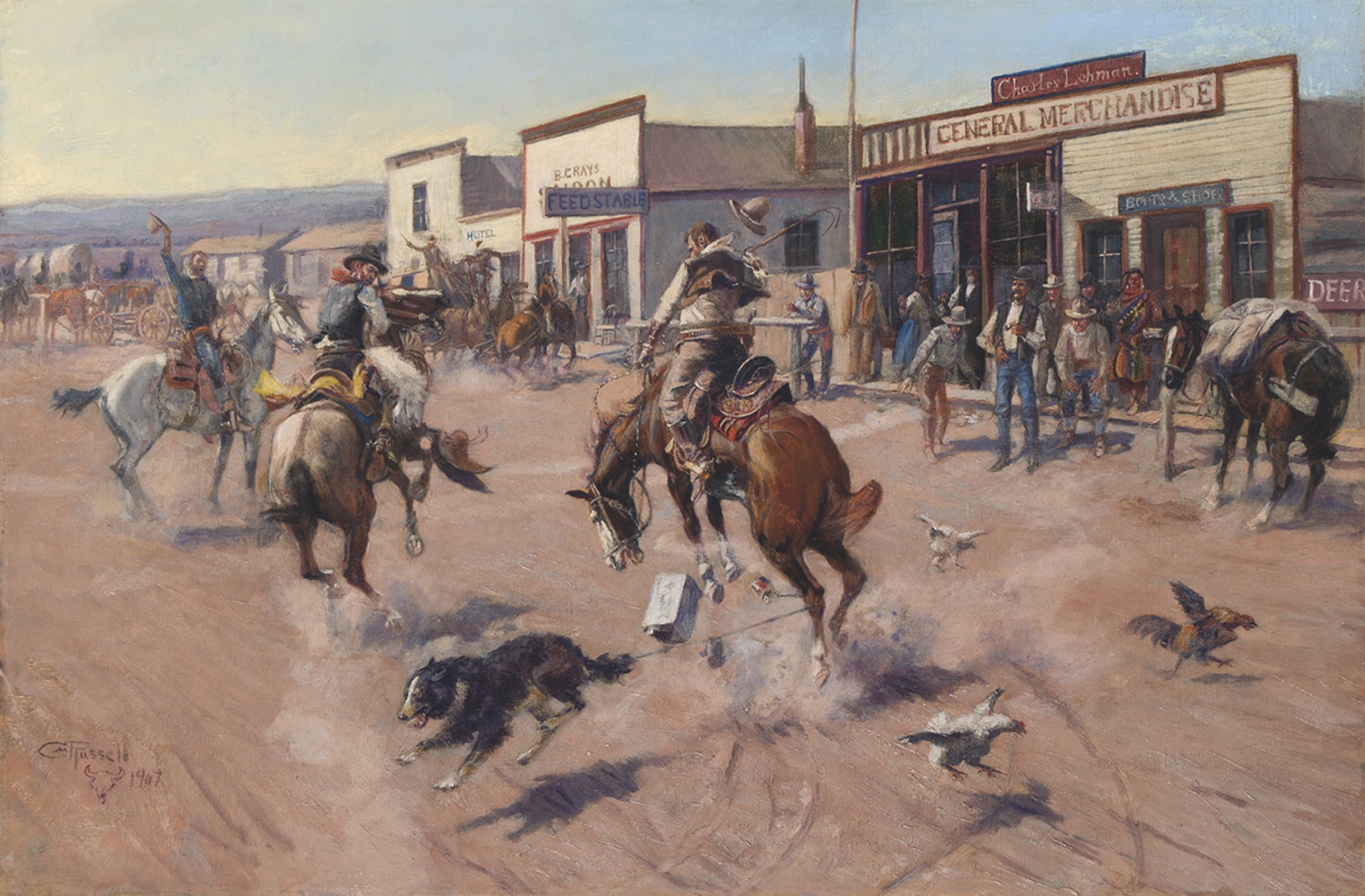

From dime novels to museums, Western pulp art and illustration has reached its zenith.

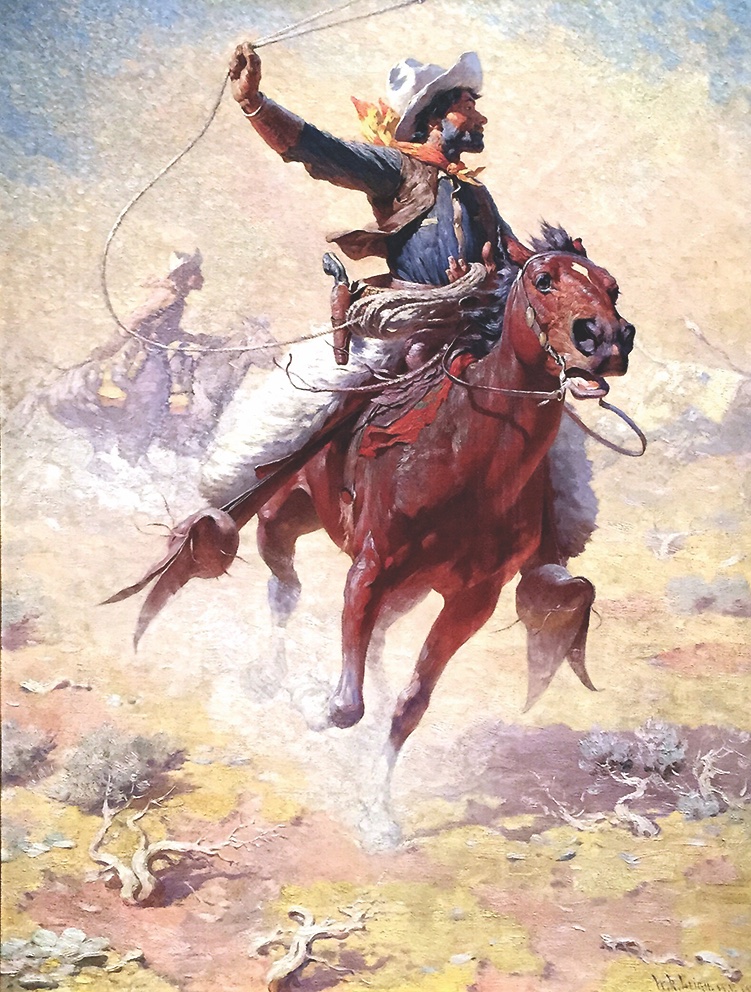

A.R. Mitchell drifted into the office of Cowboy Stories magazine in the late 1920s with a painting to show editor Harold Hersey. “Mr. Hersey, I’ve tried to paint the real cowboy,” Hersey recalled the artist saying, “not the movie variety.”

The painting appeared on the magazine’s January 1927 cover, launching Mitchell’s career and inspiring Hersey to write of Mitchell in the issue’s “Editor’s Notebook”: “He refuses to compromise for the sake of popularity, but like all sincere and great painters, he will get the popularity he does not seek….”

Courtesy The Phippen Museum

True West Archives

Illustrators certainly influenced pulp art, says Allyson Sheumaker, executive director of the A.R. Mitchell Museum in Trinidad, Colorado, which celebrates its 40th anniversary with a fundraising ball October 2. [See the Old West Saviors column on the A.R. Mitchell Museum on page 14.]

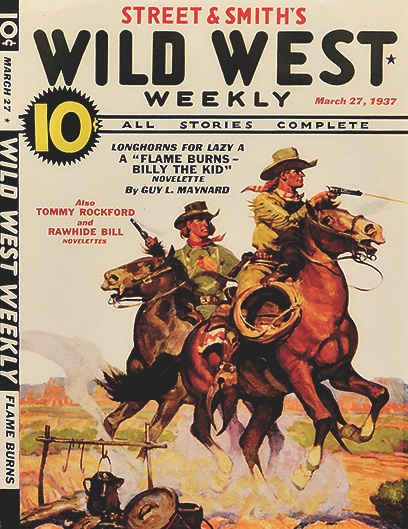

“I think Western illustration was the foundation for Western pulp art,” Sheumaker says. “The art on the cover of pulp magazines is what drew the reader in. It is the reason the publication was purchased.”

But did great illustrators become great artists because of their illustrative careers or were they great artists to begin with?

Courtesy Sid Richardson Museum

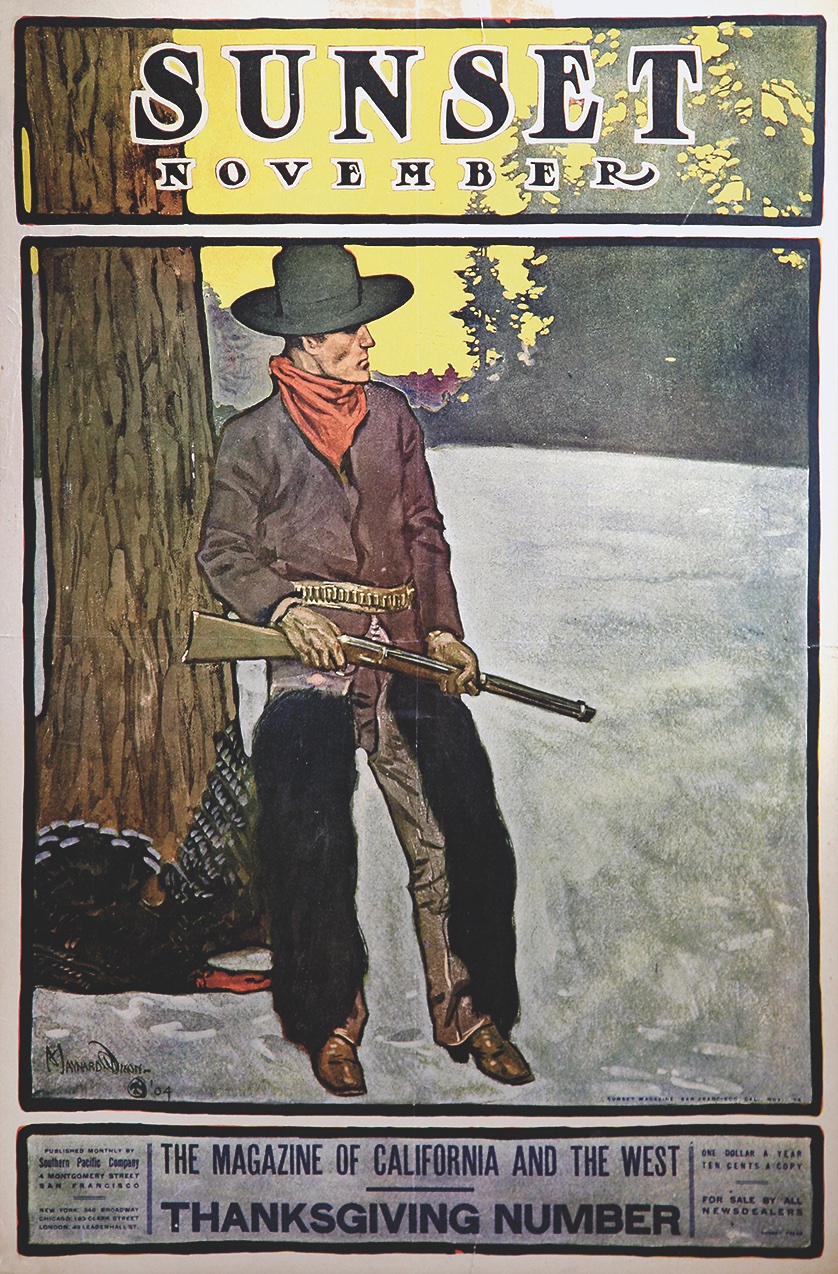

Take Maynard Dixon, an iconic Southwestern artist and member of the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame. Dixon, says Mark Sublette, owner of Tucson’s Medicine Man Art Gallery, “said he learned more about being a fine artist by working for the large San Francisco advertising firm Foster Kleiser than during any other training. His illustrative legacy continues its roots through today’s successful crop of contemporary Western artists who channel his sense of color, strong lines and powerful composition in their fine art paintings of the Modern West.”

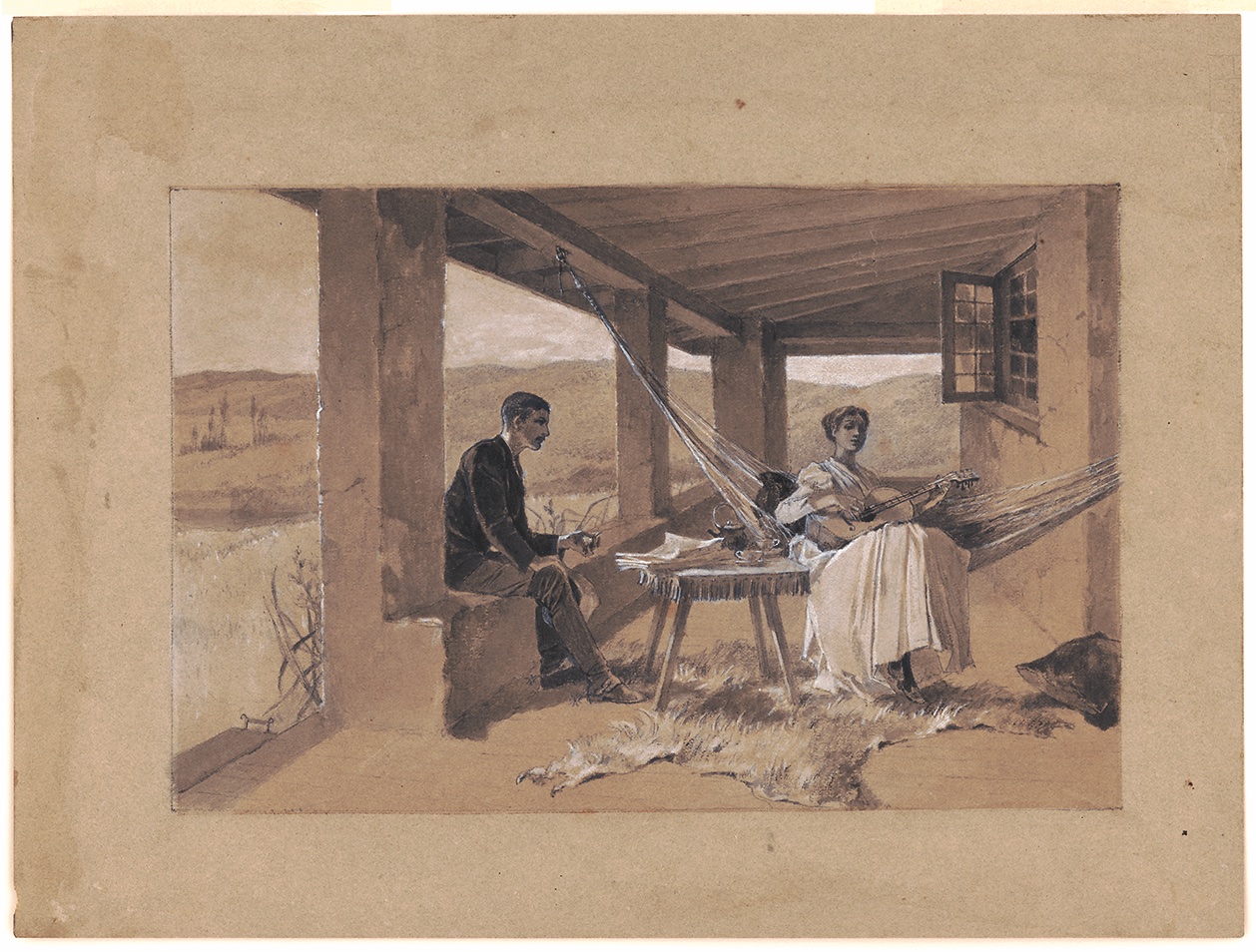

Early illustrators weren’t all men. Mary Hallock Foote was an author and illustrator for many publications and became one of the renowned women illustrators of the 1870s and 1880s. Her “realistic depictions of landscapes in Idaho, Colorado and California, helped shape the American view of the Far West as a prospective home for women and men,” historian Chris Enss says.

Courtesy Medicine Man Gallery

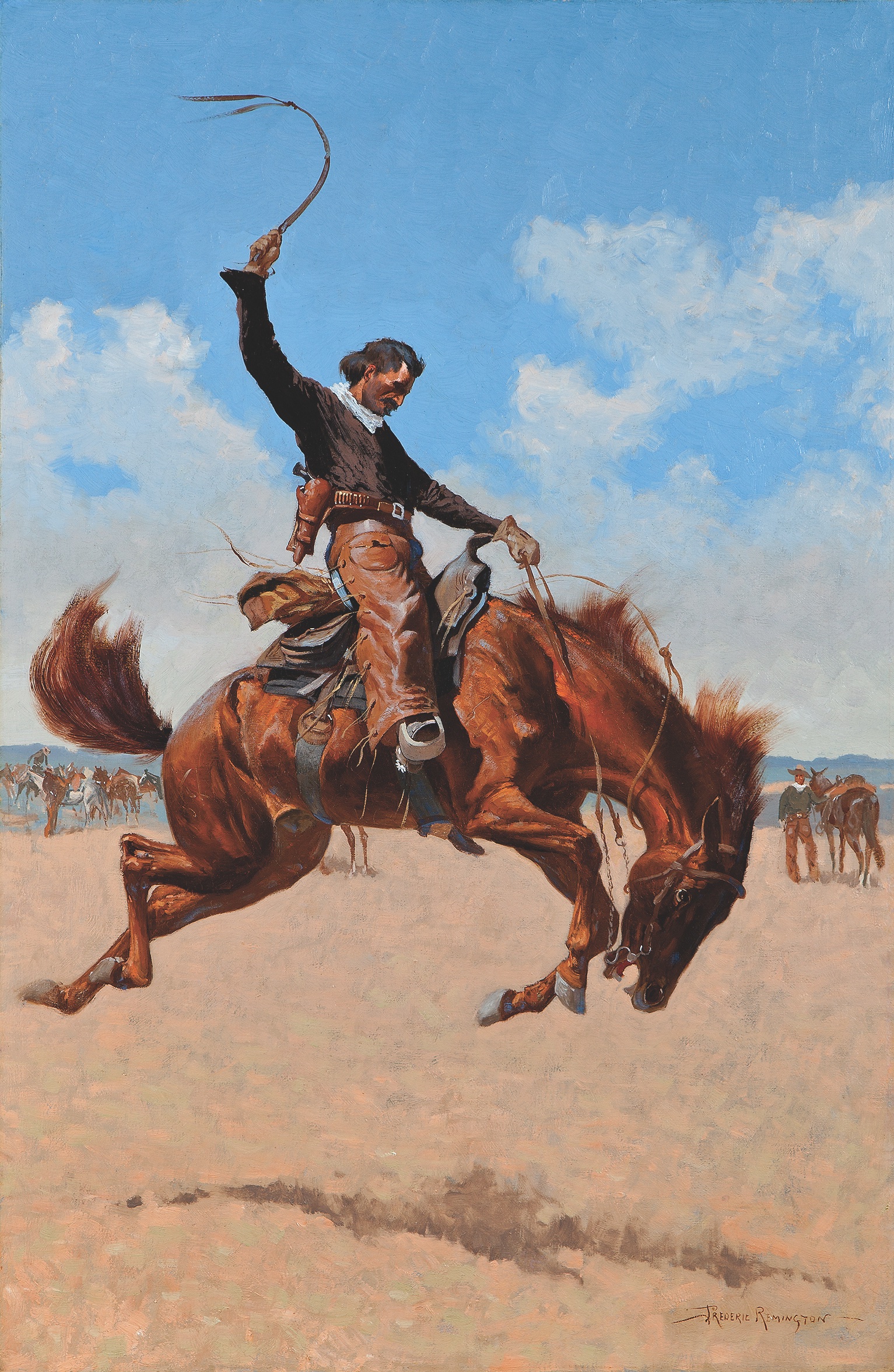

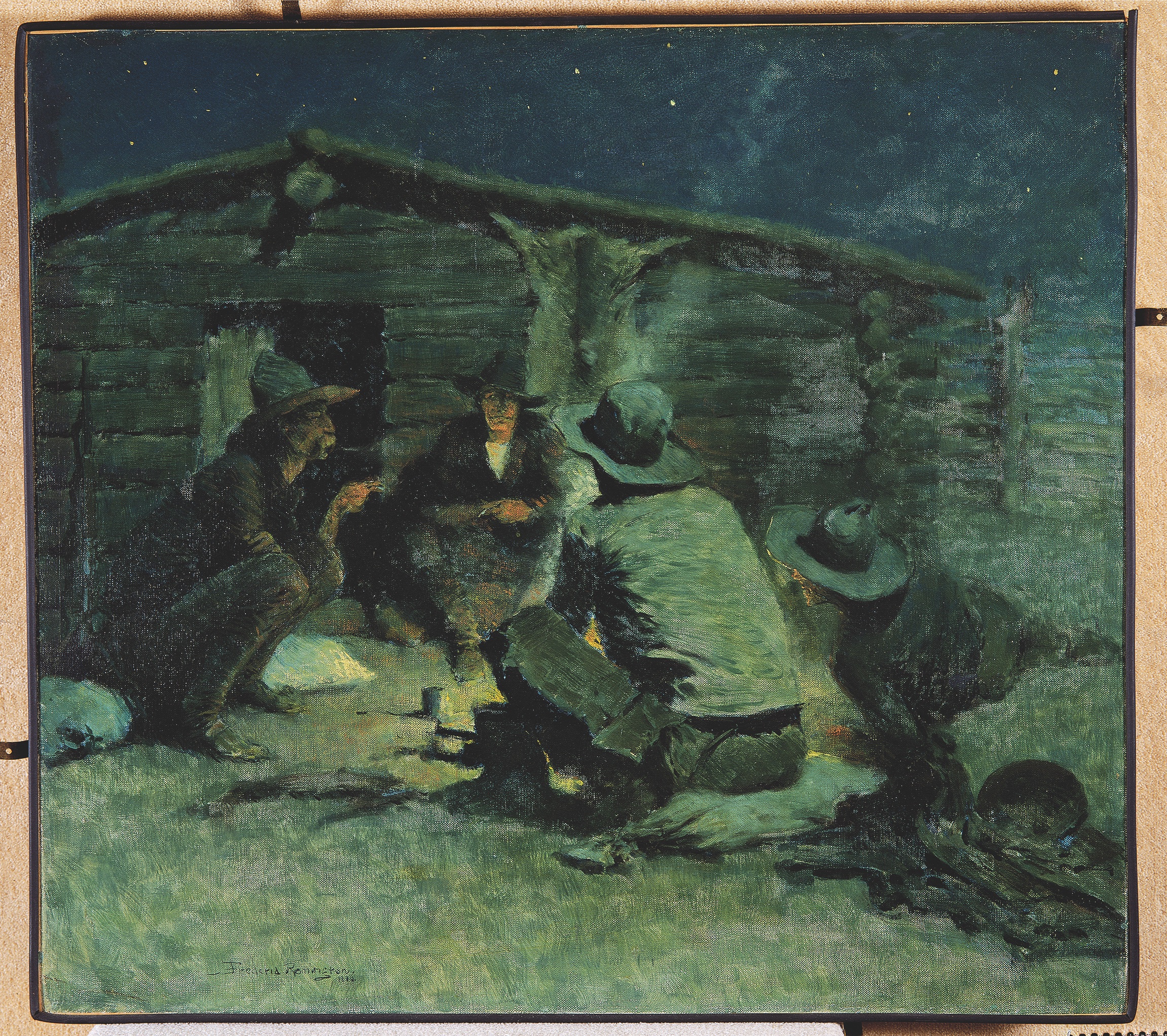

Frederic Remington’s first illustration was done as a Yale student for the Yale Courant. By the 1880s, he was established as an illustrator. “But,” says Laura Desmond, curator at the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York, “he learned quickly that in the minds of the critics, there was a divide between illustration work and fine art, and though he’d received some early critical accolades, and exhibited his work at least annually throughout his career, his prodigious production of illustration work had to some extent pigeon-holed him as a mere illustrator in the eyes of the critics, something that he worked hard to overcome.”

Courtesy Library of Congress

Courtesy Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art

Courtesy The Brinton Museum

Courtesy National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

Courtesy Delaware Art Museum

Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum

Courtesy Woolaroc Museum

Courtesy Library of Congress

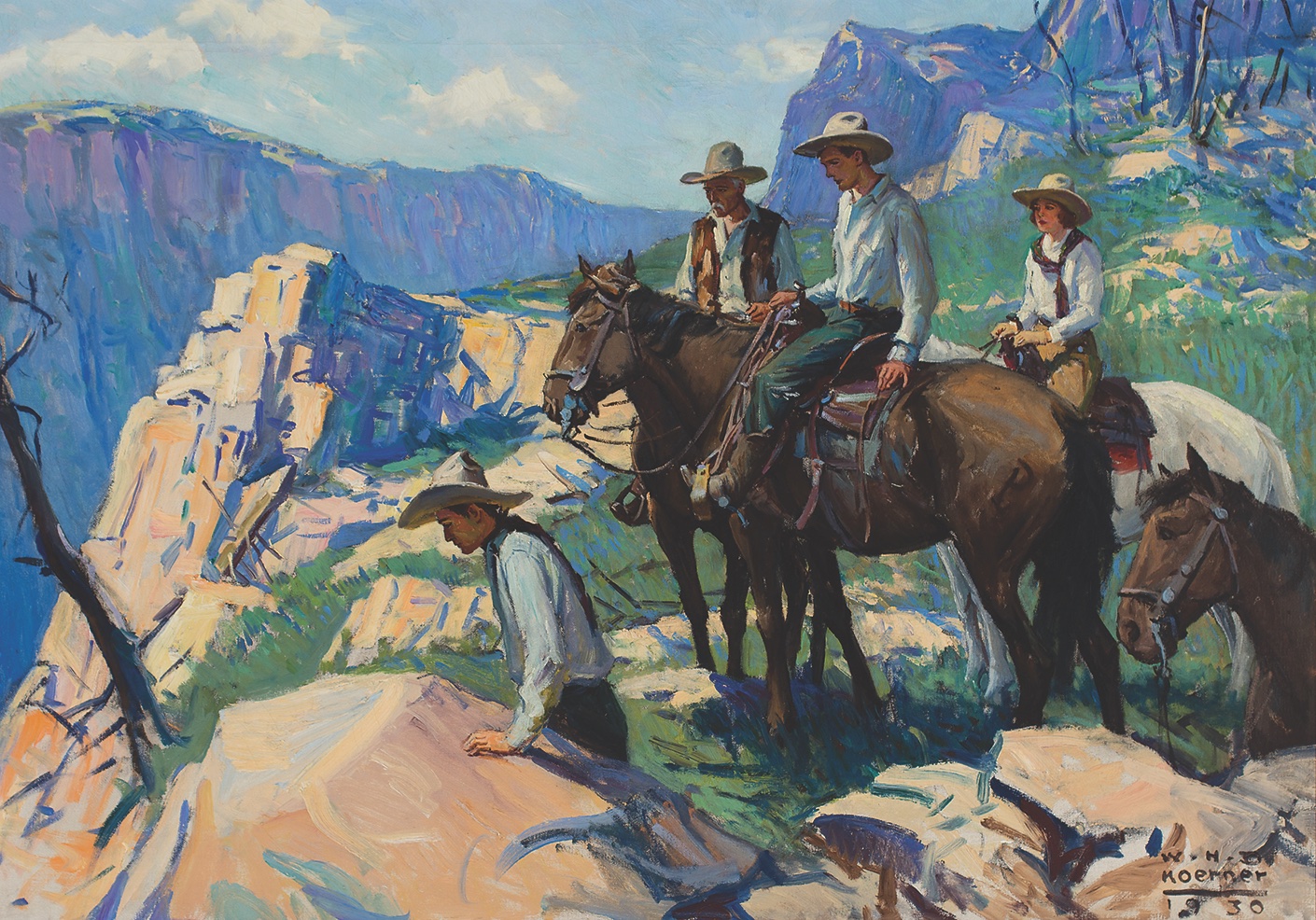

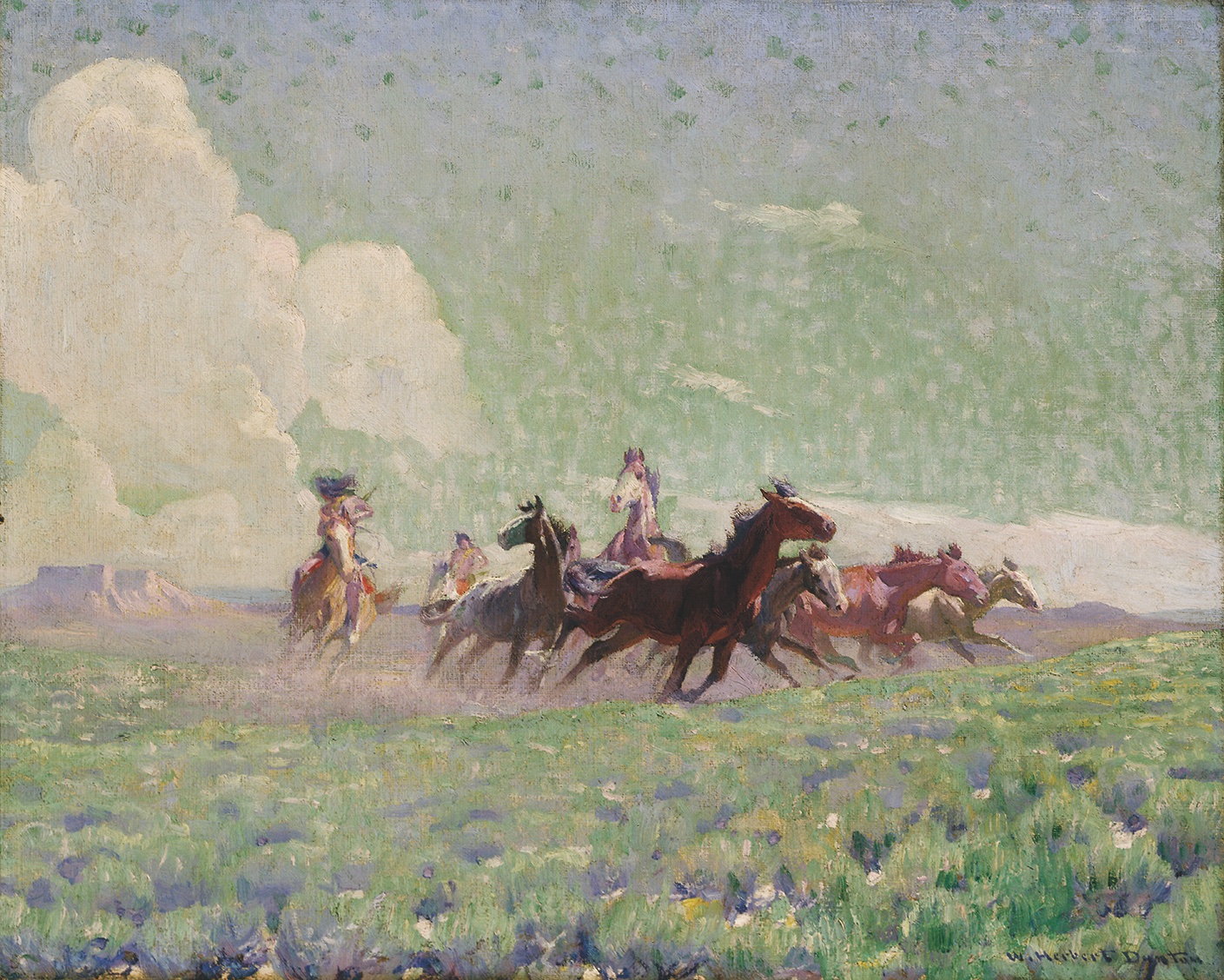

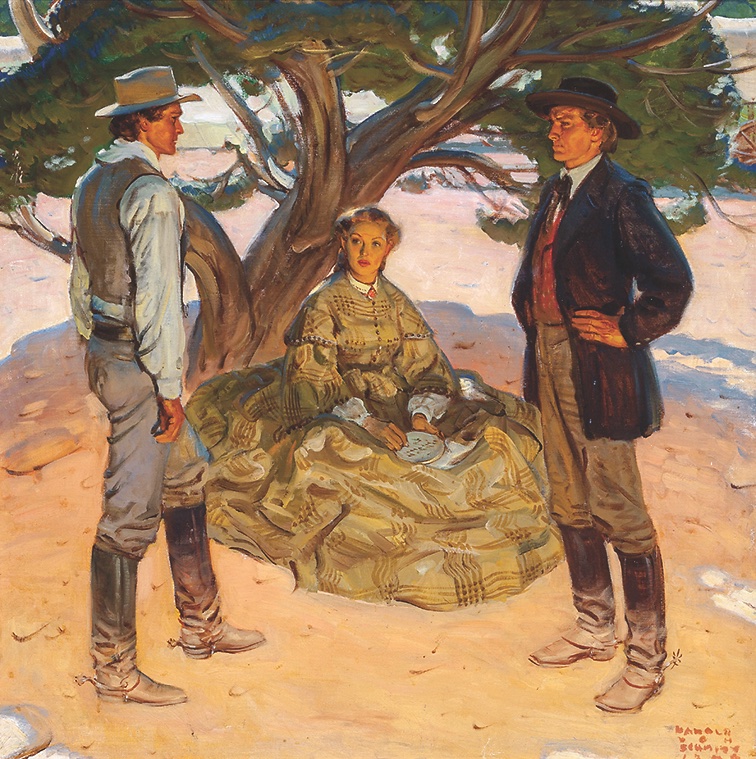

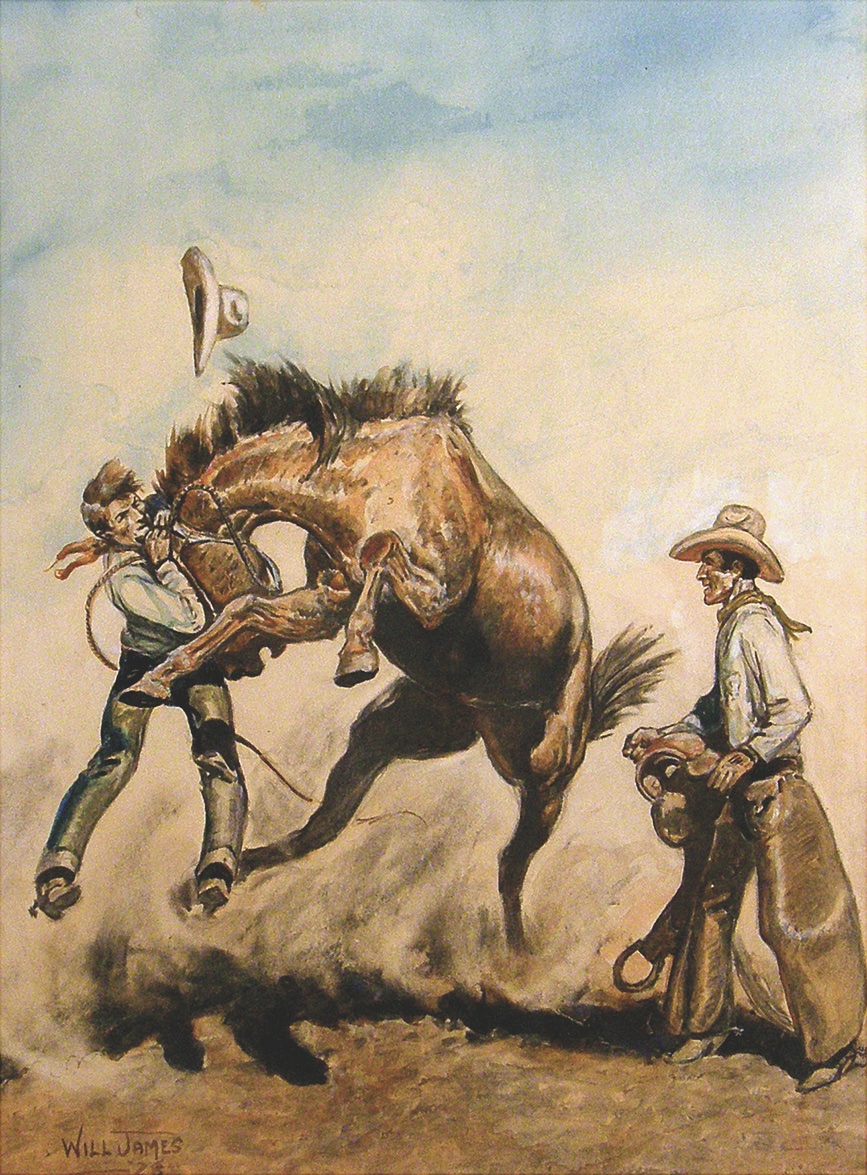

That hadn’t changed during the Golden Era of the American Illustrator (1900-1930), which produced a number of successful artists, including W. Herbert Dunton, Frank Schoonover, Philip R. Goodwin and W.H.D. Koerner.

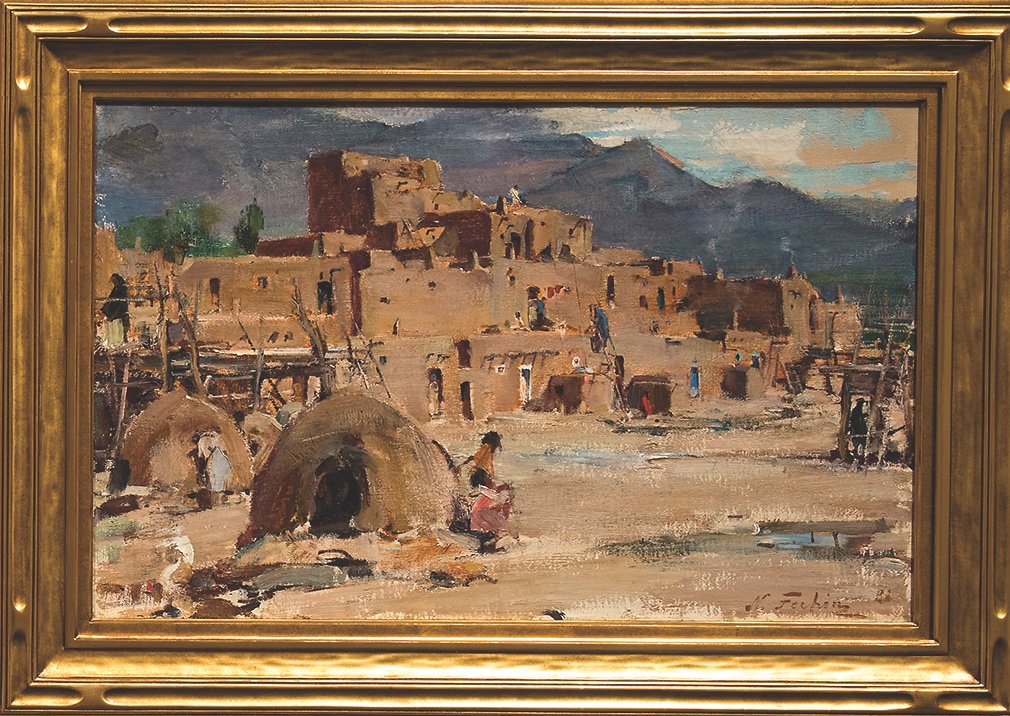

“Dunton gave up his career as an illustrator when he moved to Taos in 1915,” says Michael R. Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at Oklahoma City’s National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. “Goodwin’s work appeared everywhere, but nobody knew his name; he’s the most famous artist nobody ever heard of. Koerner and Schoonover suffered from the illustrators’ curse—a bunch of nonsense cooked up by art historians who basically said illustrators were a bunch of hired hacks.”

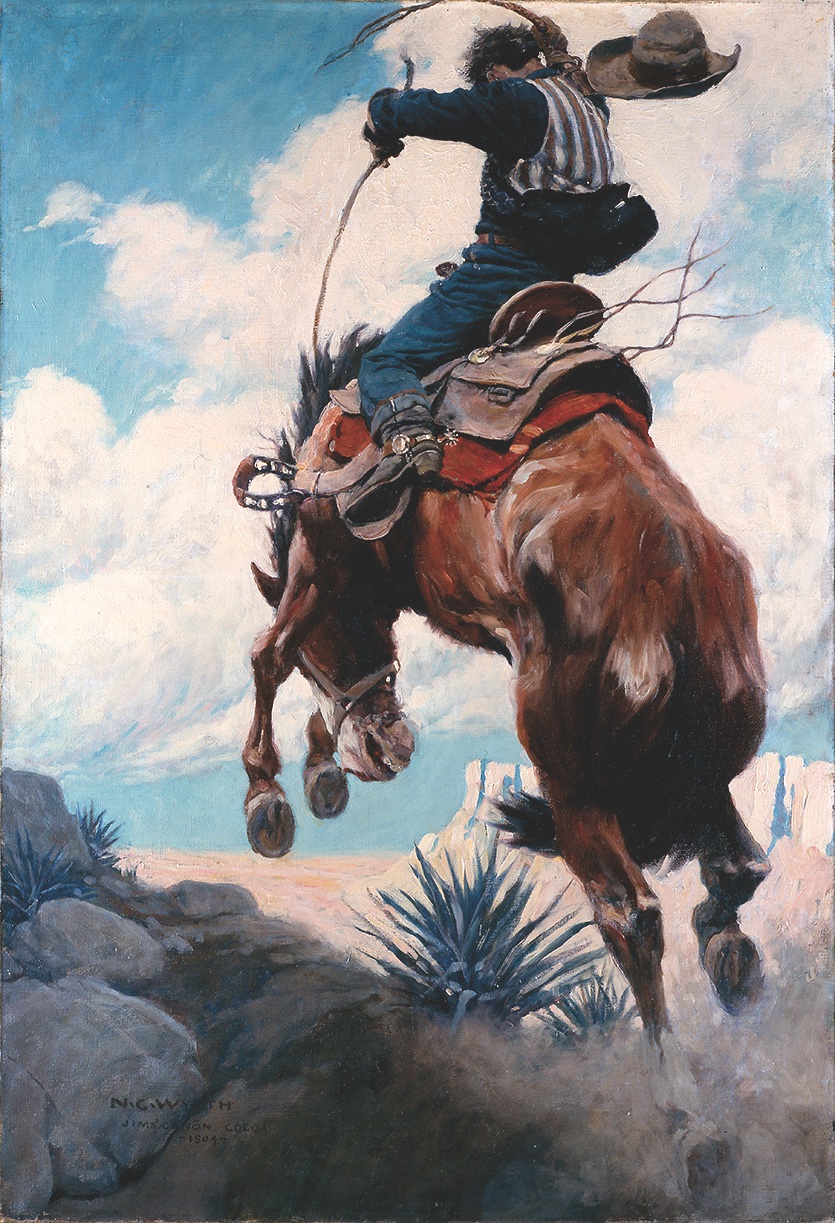

Renea A. Dauntes, archivist at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas, points to N.C. Wyeth. “He is especially interesting because he was noted for being very aware of the limitations of painting versus illustration,” Dauntes says. “The printing processes, at the time, were limiting to an artist’s imagination. Frequently, a modest color palette restricted the way ideas could be presented.”

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

Courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West

Courtesy Library of Congress

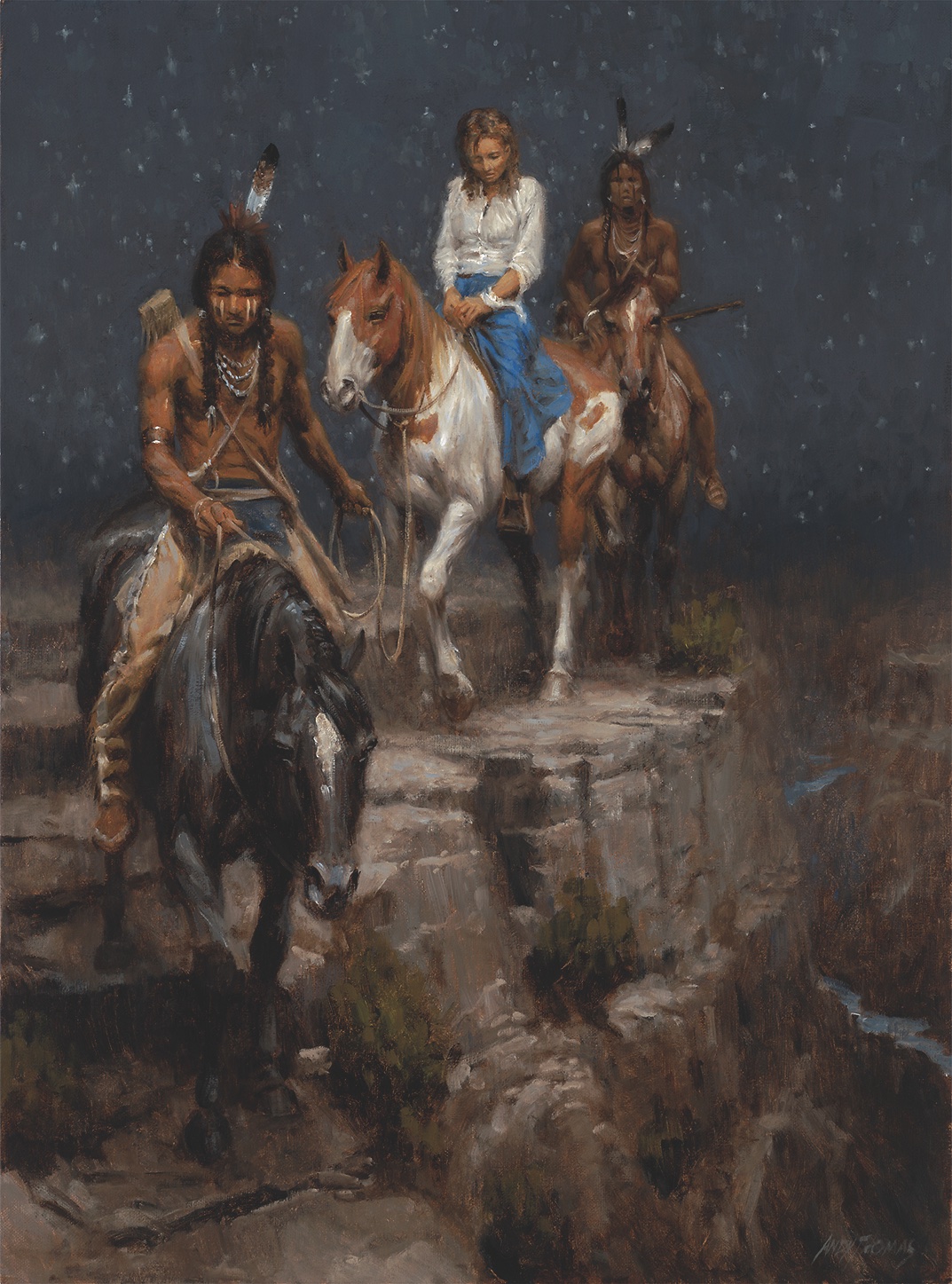

Years after the Golden Era, Frank C. McCarthy made a name for himself by having his paintings appear on the covers of myriad Louis L’Amour novels. “An illustrator is a fine artist who has to design paintings of a given subject matter around the typesetting of a page or double page, cover or ad layout for publication,” McCarthy told Western novelist Elmer Kelton for Kelton’s The Art of Frank C. McCarthy (1992). “Most painters from time immemorial have made their livings doing commissions of given subject matter.”

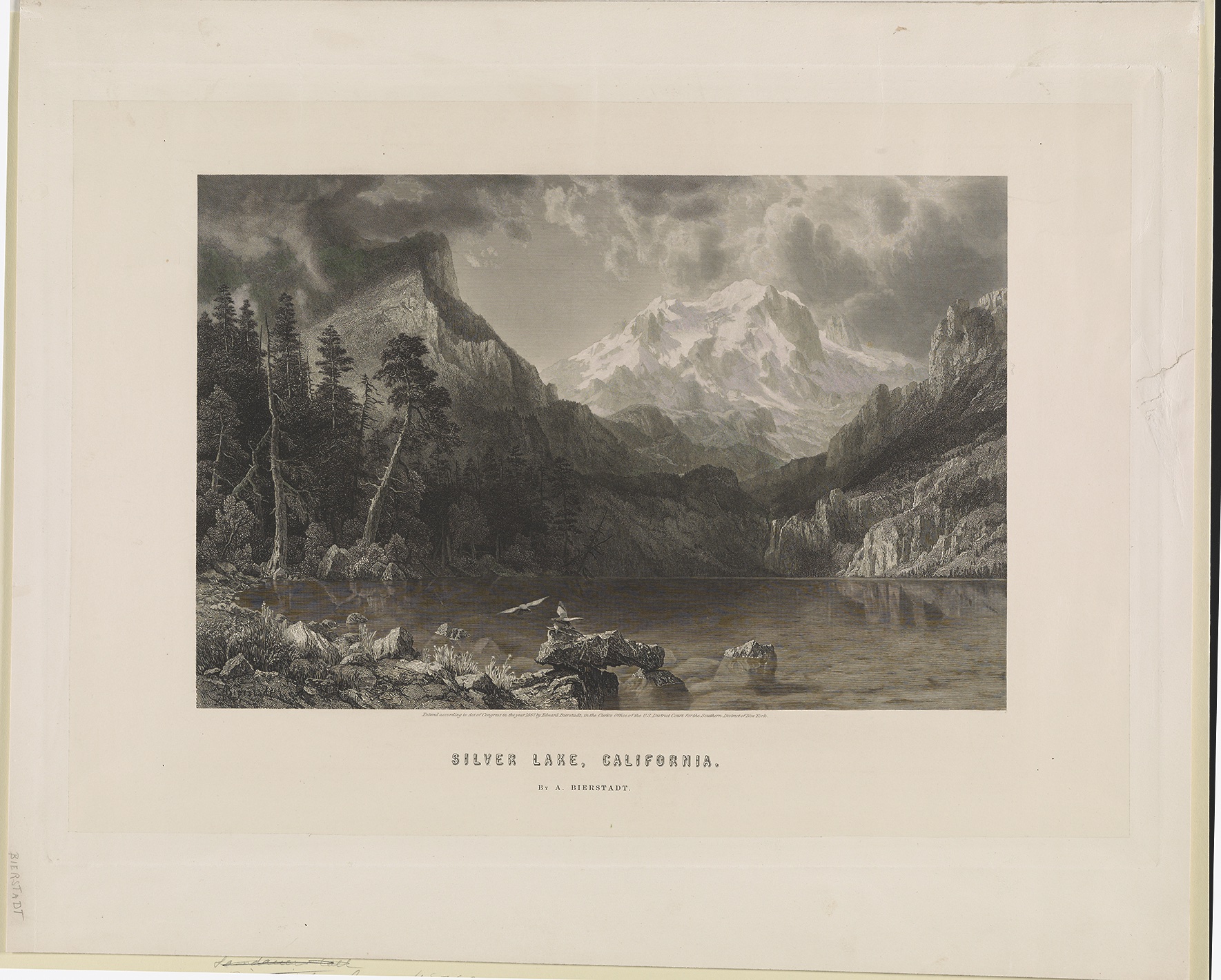

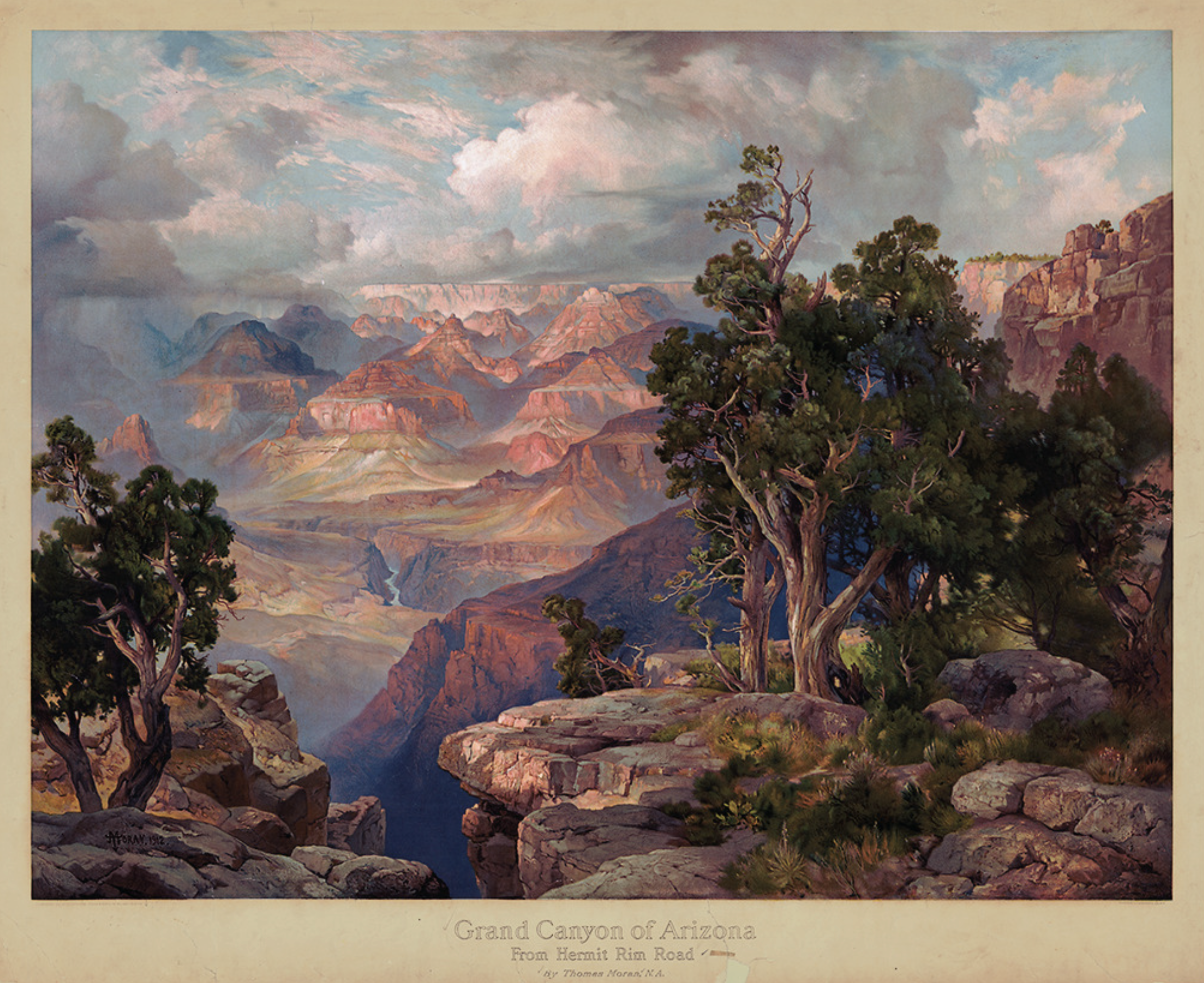

On that list you’ll find Albert Bierstadt, Frank Tenney Johnson and Thomas Moran.

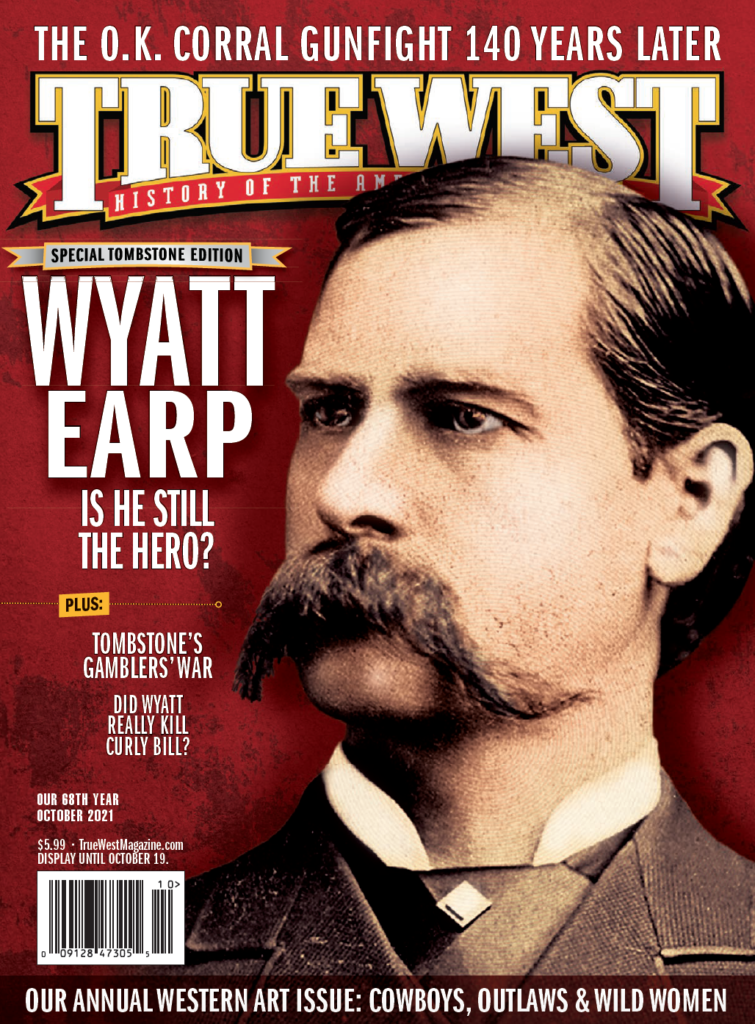

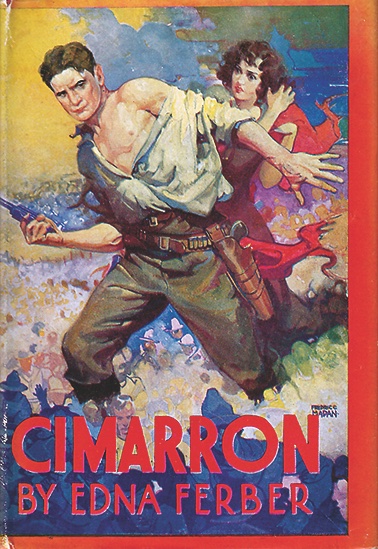

Books today, of course, still need cover art.

“There are plenty of book-cover artists today, but most of their work graces the covers of ‘bodice-busters’ or Western fantasy books,” Grauer says. “While there were plenty of clichés in the golden age, today they just seem to be cookie cutter or wash, rinse, repeat.”

But some publishers are making headway. At Blackstone Publishing, lead designer Kathryn English says, “Capturing a specific mood communicates what the book is about.”

Courtesy the Booth Western Art Museum, 2019, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

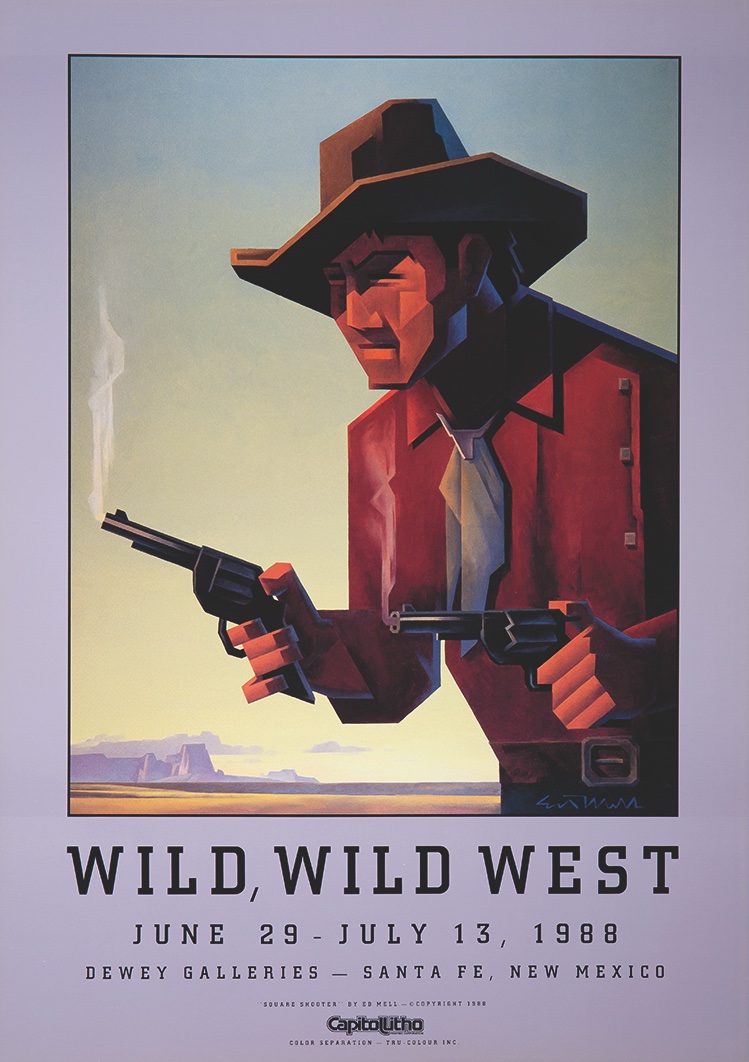

Courtesy Ed Mell

True West Archives

And these days, high-profile names are common in the illustrative world. Dauntes points to Ed Mell and Billy Schenck.

Opinions of illustrators, of course, have changed. Just ask Schenck, a protégé of Andy Warhol, a fashion illustrator who didn’t touch Westerns until his “Elvis” paintings of 1962 and several serigraphs in 1986. Schenck and Mell arrived in New York around the same time.

“When I came up, New York was the happening contemporary scene, and I perceived myself as a contemporary artist,” Schenck says. “I was such a snob, being a New York City artist. I had utter disdain for illustrators. I thought these were just second- and third-tier artists who are wannabe artists.

“As the decades rolled along, I thought, ‘Wow, these illustrators did some pretty fantastic work and after they became fine artists, they did even greater work.’ It was kind of a coming-to-Jesus meeting with illustrators. And now, for years I’ve been using movie stills as a basis for a lot of my art. So, yeah, those illustrators? They’re pretty good.”

Johnny D. Boggs objected to one of his book covers, but his literary agent told him, “Shut up. It’ll sell.” Royalty statements proved his agent correct.

True West Archives

Courtesy The Peterson Family Collection, Taos Art Museum

Courtesy Northern Nevada Museum

Images Courtesy SMoW

THE GOLDEN WEST

Rennard Strickland’s cinema collection at Scottsdale’s Museum of the West

Rennard Strickland, who died January 5 at age 80, is lauded as a champion of American Indian rights and American Indian law.

A Muskogee, Oklahoma, native of Osage and Cherokee heritage, Strickland served as dean of several law schools and introduced Indian law into the University of Oklahoma Law Center’s curriculum.

But Strickland was also an art philanthropist and collector of movie ephemera. Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West honors that legacy with an exhibit titled “Dr. Rennard Strickland’s Profound Legacy: The Golden West on the Silver Screen,” which debuted May 28.

The exhibit, a celebration of Strickland’s love for Western films and art, includes rare Western and Indian movie posters and lobby cards that date from the 1890s to the mid-1980s.

“We hope what people will get out of this is an appreciation for Dr. Strickland and what a remarkable philanthropist he was,” says Tricia Loscher, assistant museum director and chief curator. “He really brings a perspective that is unique because he interprets these posters as a critical reading and gives insight—not only to the Western films, directors and actors—but also an analysis of where we were in history, based on the films.”

Quotes from Strickland’s colleagues are posted throughout the exhibit.

In 2016, Western Spirit and the Arizona State University Foundation were gifted more than 5,000 posters and lobby cards, and “The Rennard Strickland Collection of Western Film History” ran at Western Spirit June 20, 2017, through September 23, 2018.

Estimated value of the entire collection: $6 million.

—JDB

Courtesy Sherry Blanchard Stuart

Courtesy Andy Thomas

Courtesy Kathryn Tatum

Courtesy The Phippen Museum

Courtesy Frederic Remington Art Museum

Courtesy Michael Roche