– All images Courtesy Universal Pictures unless otherwise noted –

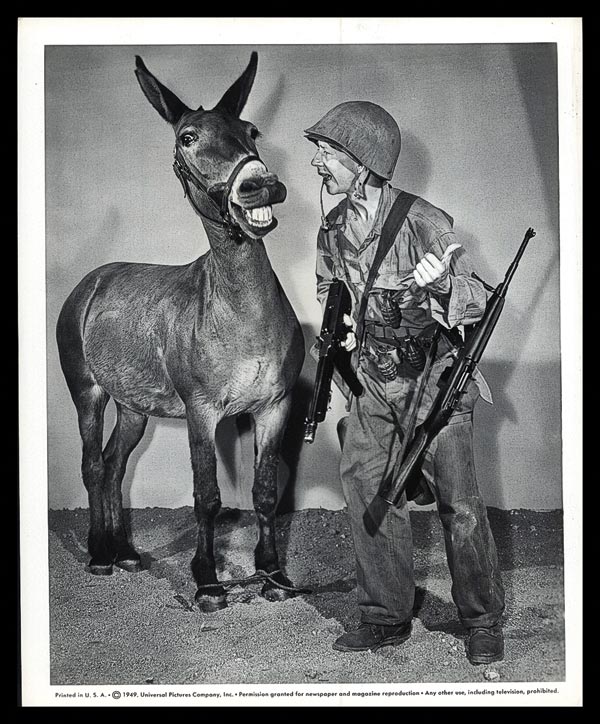

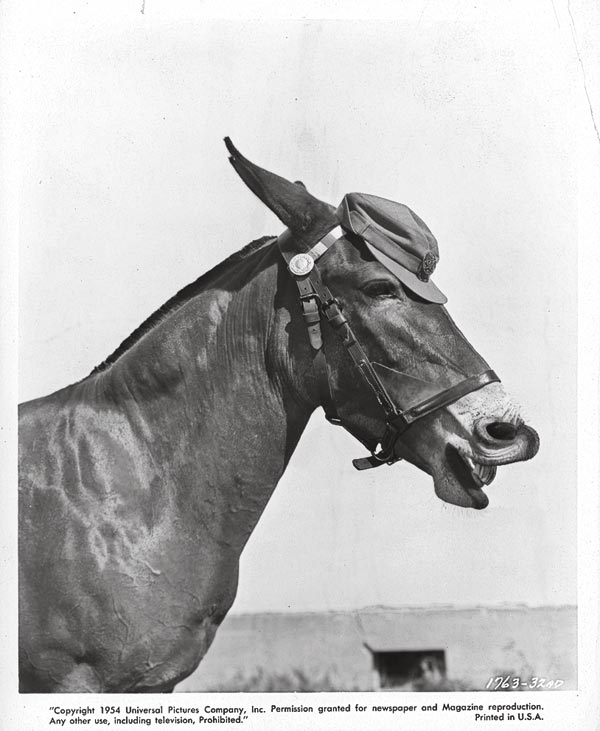

In the 1950s, Universal Pictures hit on an absurd premise that would delight millions and make millions: the Francis the Talking Mule military comedies. Audiences never guessed that Francis’s true identity was a more guarded secret than the technique that made him appear to talk.

The inspiration for Francis came during WWII, in 1943, when David Stern III was stationed in Hawaii, co-editing a U.S. Army paper, Midpacifican. “To pass the time,

I wrote four pages of dialogue between a second lieutenant and an Army mule,”

he says. “I had no intention of writing

more. But that little runt of a mule kept bothering me.”

Those pages became a short story, then a string of them for Esquire Magazine. The basic premise was that, while at war, an inexperienced soldier is aided by an experienced Army mule.

After Stern combined three of the stories

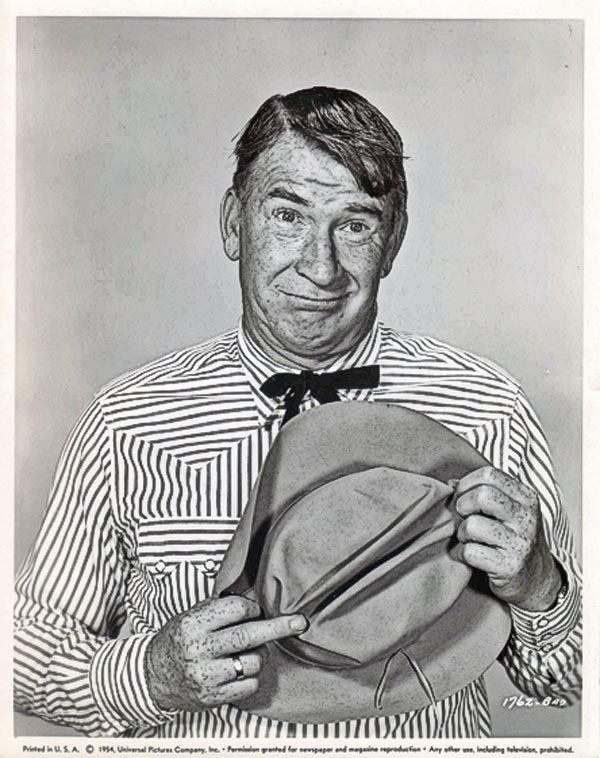

into the book Francis in 1946, Universal snapped up the film rights. Director Arthur Lubin, whose Abbott and Costello comedies had made Universal a fortune, was an ideal talent to direct the series. The studio chose acrobatic star comedian Donald O’Connor to play the soldier. As the gruff, but lovable voice of Francis, former Minsky’s Burlesque comic and George O’Brien sidekick Chill Wills perfectly filled the bill, although without billing, to maintain the illusion.

The most crucial casting was the role of Francis. Universal claimed Francis was played by a female mule, Molly, purchased from Jake and Jenny Frazier of Drexel, Missouri, for $350. The truth, published here for the first time, is that the mule who played Francis was, well, rustled.

As 93-year-old Tansy Smith tells True West, Francis, actually Judy, was the pet mule of her stepfather Archie Dean, who ran a mule pack train for tourists in Independence, California. “It was quite a popular place because Archie, as a young man, had worked for the studios,” she says.

Dean regularly supplied horses and mules to the studios. Initially, Universal had bought a mule named Billy for $100, but returned him as unsuitable. Universal wanted Judy. Dean was reluctant. “Archie’d raised her, and she was a favorite,” Smith says. “Judy was a very pretty color, a bay mule with black points. She was very calm, affectionate. She roamed free around the pack station.”

But the studio wore Dean down. While he would not sell her, “for love or money at any price,” he agreed to loan her out, as long as she was returned for pack season in May. “But,” Smith says, “that didn’t happen.”

After repeated requests for Judy’s return, Dean was told by a studio representative, “Oh, you don’t want her back: we have taught her to kick.” He replied, “Yes I do. I’ve taught her practically everything she knows, and I can unteach her how to kick.”

Archie hired an attorney to get Judy returned. “Universal just dug in their heels,” says Petrine Day Mitchum, author of Hollywood Hoofbeats and daughter of actor Robert Mitchum. “Judy had become very famous and was worth a lot of money, and they just weren’t going to let her go. He didn’t want to sell her: he had made that very clear. Universal’s ultimate position was they had bought Billy, he was unsuitable, and they exchanged him for Judy.”

– Courtesy Capitol Records –

Archie never got Judy back. The statute of limitation for the theft had already passed.

So how did Hollywood get its rustled mule to talk? That job fell to Lester Hilton. “Les was a protégé of Jack ‘Swede’ Lindell, who was very well known for training Rex, King of the Wild Horses,” the biggest equine movie star of the silents, Mitchum says. “He taught Judy to climb stairs, untie a rope and wink. She flatly refused to sit, so another mule was brought in for those scenes. Les tried different ways to make her talk—chewing tobacco, gum—but nothing worked. So he devised a bridle or halter with a heavy filament thread running under her top lip, so that when the thread was pulled, she’d wiggle her lips.”

When Francis made a rare live TV appearance on What’s My Line, Hilton stood

beside Francis, tugging the cord from the bridle. Theories abounded about how the mule talked, from the plausible—peanut butter under the lip—to the upsetting—electric shocks—but the trick was in the thread.

While the Francis films were a favorite with audiences, they weren’t with Universal contract players; they certainly added no prestige to the résumés of Tony Curtis, Piper Laurie and David Janssen.

Blonde bombshell Mamie Van Doren, who costarred in 1954’s Francis Joins the WACs, remembers, “I adored Francis more than any other actor on the set—believe me! But I really didn’t want to play opposite a mule. The Francis movies and the Ma and Pa Kettle movies were the ones you tried to escape. But when you’re under contract, you have to do what you’re told. Clint Eastwood was under contract, but I was further up the ladder. Clint asked me if I could get him into the movie. I said no, I was trying to get out of the movie. When they did the next one, Francis in the Navy, he was in it.”

After six Francis films, the team disbanded. One more film was made, in 1956, Francis in the Haunted House. The original cast was replaced with top talent: Charles Lamont directed, Mickey Rooney starred and Paul Frees voiced the mule. But even with Judy still in her role, the movie didn’t have the magic, marking the end of Francis films.

Yet talking equestrian comedy was not finished. Lubin developed Mister Ed for television, with Hilton using his same technique to make the horse speak. Alan Young starred as Ed’s befuddled owner, while Allan “Rocky” Lane, the former Red Ryder star for Republic Pictures, provided the horse’s voice, like Wills, in secret.

Eastwood turned up in an episode of Mister Ed too.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com