Don Juan kept his little band of mares in the pine forest at the edge of a pond.

He was alert but unconcerned. Life was good for the stallion. Plenty of prairie grass flourished and once a day, the feed truck spread grain on the ground so the band would get fat.

That’s all the herd of 23 Spanish Mustangs had to do, graze and look pretty, romp and run on the 11,000-acre Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary.

Susan Watt came up with the idea to create a herd of Spanish Mustangs separate from the 500 wild horses that run free in the sanctuary. As the program development director at the sanctuary, Susan wants to preserve a bloodline that can be traced back to original horses brought to the New World by Spanish conquistadors.

Columbus’s Gift to the New World

Christopher Columbus introduced horses to the island of Hispaniola on his second voyage of discovery in 1493. Until that day, only vestiges of Eohippus, the earliest-known horse that was the size of a tiny dog (about eight inches tall at the shoulders), remained as geological fossil records.

Columbus was at first angered that his demand for Andalusian horses was not honored and instead, small, Iberian Sorraia were boarded for the long voyage across the ocean. Yet the Andalusians probably would not have survived, while the hardy Sorraia horses flourished in the new colonies.

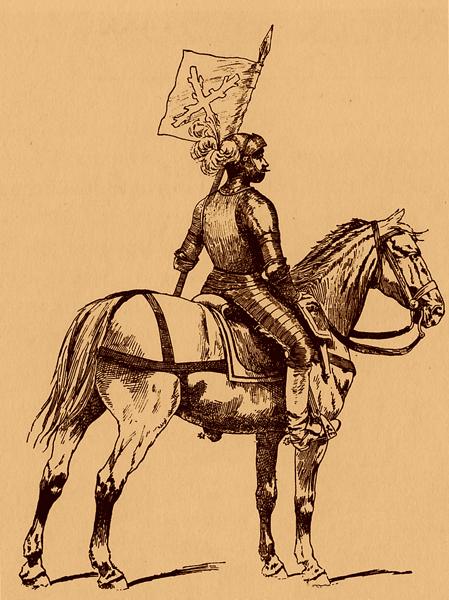

Horses aided in conquering the Aztecs, subduing the Incas and enslaving the Mayas. Without them, the conquest would not have been possible.

“Imagine a handful of men on horseback. The Aztec legend foretold that a light skinned man with a beard, riding such an animal, would rejoin his people. It was their god Quetzalcoatl, the god of day, returned as the Aztec calendar predicted. Cortez was one lucky dude. He just happened by on that very week when the return of their god in man-form had been predicted,” Vic Benilous says.

Vic is an ocean explorer. He discovered the lost treasure of Hernando Cortez in the Atlantic Ocean on a shipwreck lost in a fire at sea.

The historic record documents Cortez’s landing on the coast of Mexico at a place he named Veracruz in 1519, with 16 horses. The conquerors astounded the natives with their vast strength in numbers and even more so with the apparition of Spanish steeds. These gods on horseback received offerings of pure worked gold and exquisite silver.

The European lust for gold eventually could only be surpassed by the Indian lust for their horses.

By 1519, the Spanish colonists not only bred Sorraia or Marismeno stock but also had horses of North African Barbs when they interbred with Andalusian and Arab stock.

A long time had passed since the Moors, who invaded Spain in AD 711, were driven out of Iberia. During Moorish occupation, they exported many Sorraia horses, indigenous to the southern Iberian peninsula, across the sea to North Africa. Andalusians cost 10 times what Sorraias cost and would not endure the privations and hard work demanded of them in the tropical colonies.

During the continual trade over the years, horses that had been exported to North Africa were bred by the Moors and Berbers with Arabian horses and horses of the Barbary Coast. These horses were then exported across the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain and Portugal. This breeding yielded reliable mounts of great endurance.

Of this stock, inevitably, Cortez was furnished his horses from Cuba when he set sail for Mexico. The adventurer took brown, bay, black and grays, according to Spanish records. These were durable horses that could survive the long sea voyage across the gulf to Veracruz.

In time, many different breeds of people ventured to the New World. A variety of horses accompanied them into the Americas. Work horses, Nordic horses, European stock as Dutch settlers came to New Amsterdam, English to Plymouth Rock, French to Arcadia. Eventually their bloods mixed during Western expansion.

Yet it seems that little bands of Spanish Mustangs, like those in the Mountain Home Range in Sulphur Springs, Utah, kept apart from other horses. Because of this isolation, the bloodline has been preserved better than most.

The horses from early Spanish adventures into Florida likely didn’t survive the ordeal. Those horses were killed for food, murdered by the native people or died from starvation and the perils of the swampland they invaded.

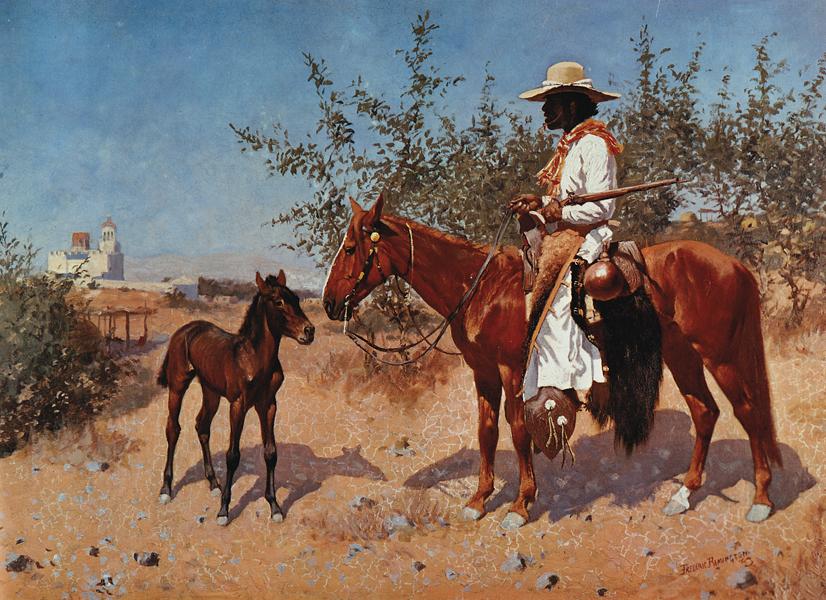

Yet the horses from the Spaniards’ western movement—through Mexico into California, Texas, Arizona and the New Mexico, Utah and Colorado Territories—fared better. From the mestas—the Spanish horse farms of the hacienda and ficas of Old Mexico—and the vast Spanish territories, horse blood remained as pure as it could, for a time, and the breed thrived.

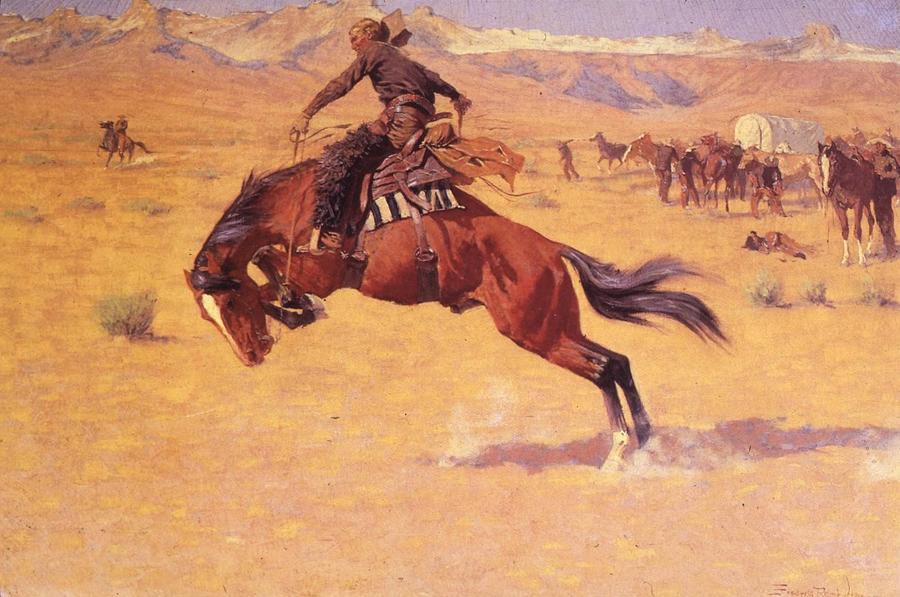

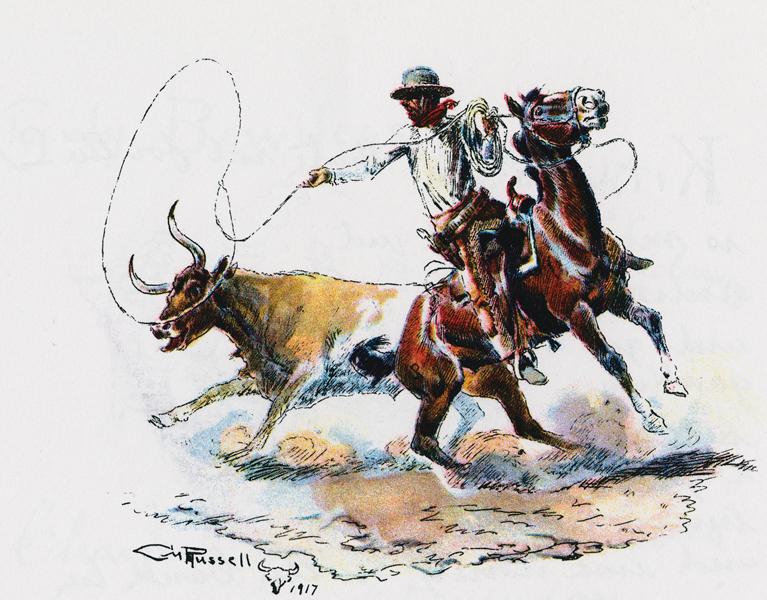

Tribes stole horses, traded for them, captured mestenas (mustangs) that escaped from the mestas and the farmers who raised the steeds. Plains Indians learned quickly how to domesticate the horse. They hunted bison by horseback, used them as beasts of burden and quickly became horse cultures while before dogs had served their needs for domestic animals.

From Millions to Thousands

In the American West, wild or feral horses accentuate the traits of most every breed that was introduced by waves of settlers and pioneers.

Plow horses mixed with thoroughbreds, Morgans mixed with Arabs. The little Iberian horses from the Sor and Raia tributaries that formed the Sorraia River in Portugal on the Spanish border ran wild with vast herds that numbered two million on the Western frontier in 1900.

That number was culled to fewer than 20,000 by 1971, after systematic slaughter of wild horses for pet food, fertilizer and sport reduced the wild herds.

Some protection was afforded feral horses under the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971. It is a law continually eroded by human greed, arrogance, expansion, population explosion, development and competition for rangeland. The latest incarnation was in 2004, when President George W. Bush’s administration removed protection for wild horses and burros that were over the age of 10 or were unsuccessfully adopted after three attempts. Since these feral horses are sold without restrictions, it’s likely that many were sold to slaughterhouses. (Congress is currently considering a bill that will ban the slaughter of horses for human consumption.)

The path of destructive legislation has left merely 31,000 wild horses in the American West. About 2,000 living horses are registered in the Spanish Mustang Registry, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Of those, less than 200 are the pure blood Sorraia horses first brought over to our country by Columbus and Cortez.

“Spanish Mustangs were the Indian ponies. They are descendants of the feral horses brought over by the Spanish. These Spanish Mustangs today are what Mother Nature worked out. Nature is a better breeder than us. If something is not fit, it gets ate,” Sharron Scheikofsky says.

Sharron began working with Spanish Mustangs 30 years ago. She was inspired by Bob Brislawn, who she says “began in the 1920s to save the true Spanish Mustangs from being bred out of existence. His son Emmett has devoted his whole life to them.”

Bob Brislawn was the founder of the Spanish Mustang Registry, with its 2,000-strong membership of horses. Bob started the registry in 1957 with just 20 steeds, after half a century of breeding and recording the bloodlines of Spanish Mustangs.

Bloodlines play a huge role in determining whether or not a horse is a Spanish Mustang. Yet mitochondrial DNA tests can be misleading. The genetic material is definitely more reliable than nuclear DNA, in that mitochondrial DNA usually shows no change from parent to offspring. Sounds foolproof, right? Except the DNA only accounts for the mother’s lineage. This means that progeny can test positive for Spanish Mustang mitochondrial DNA and look nothing like a Spanish Mustang. In that case, it’s likely that somewhere along the line, the females bred with horses outside of the pure herd.

Since a horse can test positive for the DNA and yet not exhibit the “look,” Spanish Mustangers, like Sharron Scheikofsky, view the whole horse to determine its ancestry. Sharron’s eye gauges the Spanish phenotype, the conformation typical of the Sorraia breed that is her specialty.

“In Iberia, there are about 150 Sorraia horses left. They are named for the river in Portugal in the Aleantejo and Andalusian regions where they are found. Eleven of these horses were taken from the wild by Dr. Ruy d’Andrade around 1920, and thus saved from extinction. Every Sorraia horse goes back to these 11 that are heavily inbred,” Sharron says.

“Hardy Oelke, a man from Germany, came over here. He wanted to see some [American] mustangs. The Spanish Mustang Registry told him to get in touch with us. We have more grulla types than anyone. Hardy thought that the Sorraia Mustangs might be able to help the breed survive.”

Intrigued by Dr. d’Andrade’s Spanish herd, Hardy wanted to see if any Sorraias existed in the Americas. His research was already proving fruitful; he had discovered two Spanish Mustang mares in a herd at Book Cliffs, Utah. When he visited Sharron, he tested one of her mares and discovered she also carried the Sorraia DNA.

Today, Sharron and her partner Dave Reynolds own the largest number of Sorraia Mustangs in the Spanish Mustang Registry.

Champions of the Indian Pony

Sharron, born in Salt Lake City, Utah, grew up in Denver, Colorado, where her grandparents owned horses. A picture of Cochise and an article about the horse of Spanish blood got her started on a quest to find out more about them.

“I got my first one in 1974. I found out you can’t have just one,” says Sharron, laughing, her bright blue eyes twinkling. “Every year we say we are not going to keep any foals.”

“We said ‘we are going to keep it at 20 head.’ We have 80. We broke that limit,” Sharron’s partner Dave Reynolds adds.

Dave was born in Tyler, Minnesota. He left his family’s dairy and cattle farm in 1980, when he came out to the Black Hills of South Dakota. “I liked to be where there were cattle and horses. I was tired of running farm machinery in Minnesota,” Dave says.

Dave got a job at a livestock auction yard and began shoeing horses and starting colts. “I learned horse shoeing from an old boy in Minnesota. He took me twice on his rounds and finally said that’s all I can show ya,” Dave says.

“Spanish Mustangs, there is not near as much trouble with them as with [other] horses. I was telling them ranchers about their horses with little feet and big bodies. It’s like taking a pickup and puttin’ motorcycle wheels on it. It won’t last,” he says, smiling.

Dave met Sharron at a ranch. “She had this little grulla stallion, and he had all kinds of Barb characteristics. She had the horse in Wyoming. I thought it belonged to the rancher so asked him how much. He said a friend of theirs owned the stallion. So I asked him what the friend wanted for the horse. The rancher laughed and said ‘She won’t sell him for a million dollars.’”

“I finally met Sharron, and we found out we were trying to save the same kind of horses—the Barb-type Spanish Mustangs. We decided to join in our efforts to do this in 1990. That’s how we got together,” Dave says.

“I have never seen any breed of horse with personality like them. It’s due to the fact that they’re intelligent. Man has bred so many modern breeds to put up with you that they are dull. These horses are so smart you can see the wheels turning, the things they will do. Bob Brislawn talked about their natural affinity for man. He worked for the Geological Survey and used them as pack animals. He never tied them together, never hobbled them at night,” Sharron says.

When training Spanish Mustangs, Sharron and Dave offer impeccable advice. “I always tell people to start with being their friend. Get ’em to like you, then start training,” Sharron says.

“Training varies with the horse,” Dave adds. “I always start where the horse is at. See where the horse is at, what’s scaring him, what’s he afraid of.”

“Don’t approach him with the idea of making him do anything,” Sharron adds.

“Some of these horses, their defense mechanism is real close to the surface. If you don’t approach it right, you get that self-defense to come out. People want to call it meanness. It’s not meanness; it’s what the horse had to do to survive,” Dave explains. “Wolves and mountain lions would’ve got ’em. Being this close to nature is what makes them unique. The true old Mustang horse was free and able to move on. They’re not kept in stalls, so they’re happier and healthier.”

The Spanish Mustangs raised by Sharron and Dave are free to run on South Dakota prairie rangeland year round, so they can “be able to be a horse,” says Sharron, emphasizing the love she and her partner share for these few remaining Spanish Mustangs whose blood lines and characteristics they hope to keep pure. They are not big horses, about 14 hands high, and they generally weigh 700-800 pounds.

So what exactly are those special traits of the Spanish Mustangs that Sharron and Dave are fighting so hard to preserve?

“The Spanish Mustangs have a deep set neck that starts lower in the chest,” Dave says. “Flat smooth muscling. No creases or bulgy muscles; that’s not right.”

“They have a low set tail,” adds Dave, putting his hand on the grulla’s tail, showing its position at the base. “The old Sorraia horse had either a flat or convex head.”

“We say convex rather than Roman nose,” Sharron explains. “That expression is used for draft horses. It’s not the nose, but the whole head.”

“Their feet are sounder and stronger. Very little leg and foot problems,” Dave says.

“The legs are all in proportion. Man hasn’t been screwing with them. Birthing is never a problem with these horses. In the hundreds we raised, we only had one problem,” Sharron says. “It was a foal with a leg back so the mare couldn’t have the baby.”

“That to me is amazing. We have 100 percent every year. They’re being bred naturally. The stallions run with ’em all year long. That’s a problem with [other] horses, [man] won’t let ’em run naturally,” Dave says.

“They have a narrow chest. If you look at anything Mother Nature made that’s got to move, you see they don’t have wide lungs; they are long. That narrow chest is for lung capacity. That’s for running. They’re flexible,” Dave says. “They have very smooth gaits and are sure-footed. Very good in rough country. They can jump from a standstill into a gallop.

“The back legs being under them, they have agility. Bob Brislawn used to say ‘it is like they are leaning forward on their front legs, head and legs under them. Always in a position to jump and go.’ They had to be that way in the wild.”

Healing is also fast and sure in Spanish Mustangs—necessary for survival that kept the horses alive in the wild.

“We had six or so very bad wire cuts on their legs. We’ve never had any ‘proud flesh’ problems. We never bandaged or doctored any of ’em. That’s what’s amazing to me,” says Dave, while picking up a hoof of one of his stallions.

“I used to raise Arabian horses. If you had cuts like Shadow had, you’d have proud flesh and be bandaging and doctoring it. Shadow got his foot in wire.” Dave points with his finger to the missing ball of the stallion’s hoof.

“It took a quarter of the hoof wall. The bulb of the heel is gone. He doesn’t even limp now. He barely limped when he did it.”

“It looked like raw hamburger, and he was barely limping,” says Sharron, while giving the stallion an affectionate scratch on his neck.

Clearly Sharron and Dave love their horses, almost to the point of not being able to sell the foals. “We can’t keep them all,” a disappointed Sharron says. She does admit the temptation is high when they get an exceptional colt or filly: “We want to see how it will turn out.”

Blackfeet’s Buffalo Runners

It’s clear why Spanish Mustangs are known for their endurance. “I rode out to the Brislawn ranch a hundred miles, unshod,” Dave says. “No big deal.”

A Blackfeet elder once told him, “‘They have hooves like steel … they don’t need shoes. Perhaps these purebred Spanish Mustangs, not the BLM mixed breeds, will enable our youth to understand our traditions and culture.’”

For Indians in the American West, the endurance of these Spanish Mustangs made them useful mounts for buffalo hunts. The Blackfoot is the only Western tribe known today that has taken on the mission of preserving their ancestors’ buffalo horse.

It all began when Blackfoot artist Robert Black Bull was gifted a Spanish Mustang from Montana artists Jack and Jessica Hines. The Hines had purchased paintings of his, and they felt he should raise the horses on the Blackfeet Reservation in northcentral Montana. Black Bull took the proceeds from the sale and bought six mares from the Brislawns’ ranch, where the Hines had purchased his other mustang.

He calls them “buffalo runners,” and the nonprofit program he started on the reservation in 1994 is another courageous effort to save the Spanish Mustang. The Blackfeet Buffalo Horse Coalition is a lease program that allows Blackfeet, with appropriate facilities, to lease a stallion and two mares at no cost. The lessee keeps the first foal. If two more are born, one returns to the base herd, and the other is kept. If three are born, two return to the herd, and so on and so forth.

If other native tribes in the West—most notably the Shoshoni, who were the first to revere the Spanish Mustang and referred to it as the “Dog God”—were to follow the example set by the Blackfeet Reservation, the salvation of these sturdy steeds could surely be promising.

Let Wild Horses Run Free

Susan Watt is justly proud of the band of Spanish Mustangs free to run wild at the Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary.

“They are primitive colors—duns, grullas. They have a dark stripe down the middle of their backs. Zebra striping on their legs. You see it on Don Juan the stallion and on that baby,” says Susan, pointing to a nursing foal.

“Typical is a bi-color mane that stands straight up like a Zebra on the babies until it grows out and falls over. They have dark-tipped ears. Don Juan is from the Sulphur herd in Utah. I bought some of these grulla mares from Sharron,” Susan adds.

These Spanish Mustangs are the remnants of exceptional Sorraia horses that have survived over the test of time, perpetuating the best traits selected by Mother Nature.

“Don’t mess with them,” Sharron would say. They are what mother nature perfected; tested in the crucible of wilderness to survive.

Photo Gallery

– By John Christopher Fine –

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –