The Pella Historical Society starts at home.

Certainly, Wyatt Earp didn’t play cowboys and Indians growing up in Pella, Iowa. We know because it would be decades before cowboys were glorified enough for little boys to imitate, and Indians were still too real and seen as too dangerous. But this is about all that’s certain for the years when Wyatt was a lad.

All Images Courtesy Pella Historical Society and Museums Unless Otherwise Noted

Few shreds of information exist. Maybe he pitched marbles like other boys; perhaps played hide-and-seek; probably had a slingshot; maybe staged shoot-em-up matches with his brothers or neighbor boys.

We know he and his brothers got into fights with the Dutch boys whose families founded Pella. In one, a Gaass brother took off his wooden shoe and bonked one of the Earp brothers. No report on the outcome, but it’s likely Nicholas gave his sons the win, since he bragged how proud he was that he’d taught them all to fight.

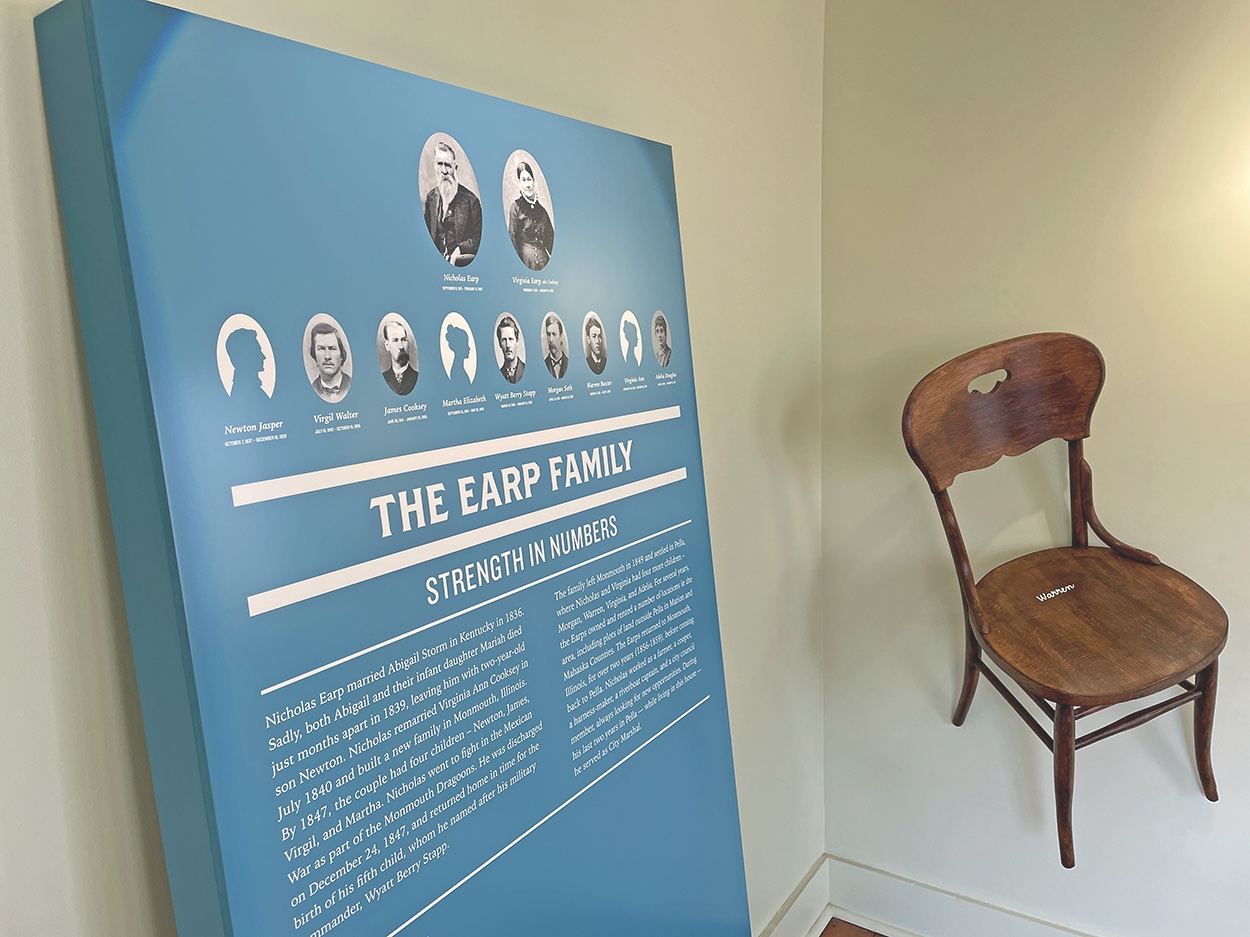

We know Wyatt loved horses, again, from his father’s tutelage. We have evidence he adored “Mother Earp.” Everyone knows he admired his older brothers and was in charge of the two younger ones, Morgan and Warren, born in Pella. Did he cry when one sister and then another died? Did he tend the boiling water for the birth of his baby sister, Adelia, who’d be the only one with him all his life? Did he go to school in Pella—a school that taught in both Dutch and English, and if he did, what kind of student was he? He had to have gone to school somewhere, since he could read and write, and he couldn’t have learned it from home because his mother, Virginia Ann, was illiterate. We know Mother taught him manners, and Father showed all his sons that a living could be made in law enforcement. Nicholas Earp was proud that most of his boys were chips off the old block.

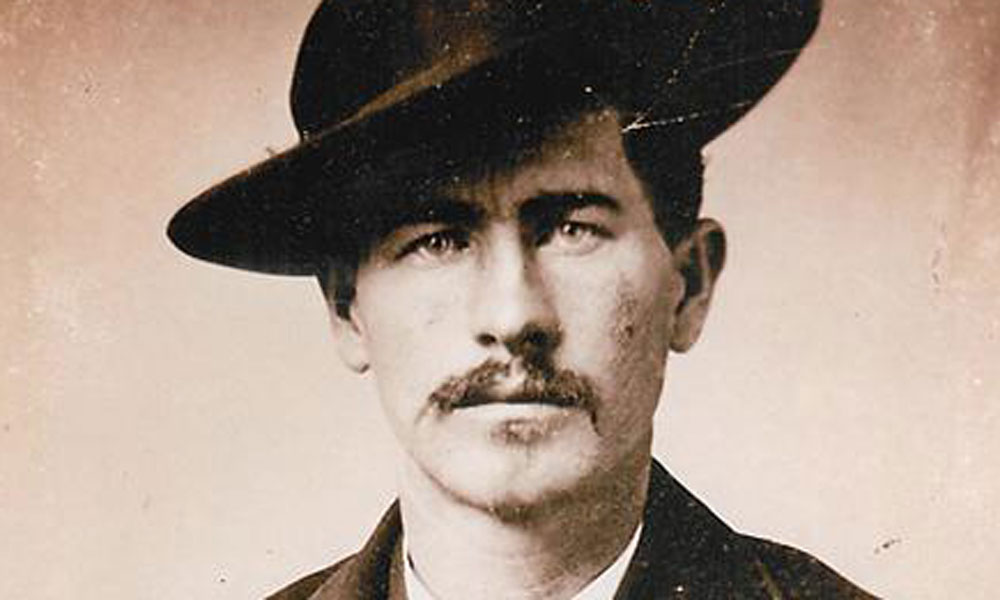

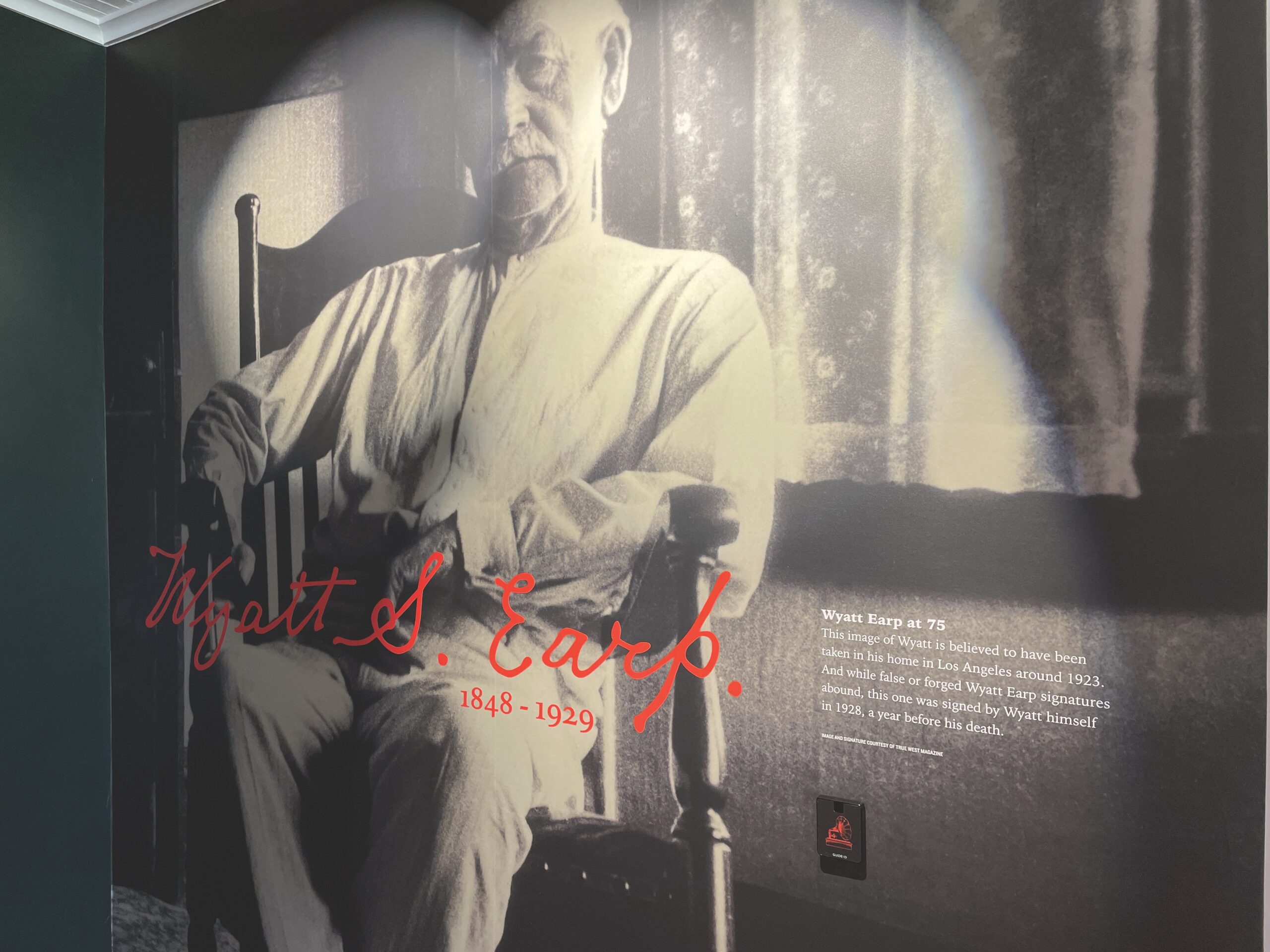

The only other certainty about young Wyatt is that he couldn’t have guessed the life he’d lead—that he’d have 80 years and become the last surviving Western legend. Imagine if he knew he’d be the only one unscathed in the most famous gunfight of the Old West near the O.K. Corral in Tombstone; that his lifelong titles included frontier lawman, prospector, gambler, saloonkeeper, boxing referee, pimp, horse thief and avenging murderer; that he’d swear off whiskey after his first drunk; that he’d be considered the “cool head” of the Earp boys; that he’d outlive all his brothers—from the most popular Virgil to the most tragic Warren; that he’d love three women—marrying only once, but becoming a widower who buried a wife and unborn child before their first anniversary, then hooking up with a woman he’d abandon in Tombstone as her addiction took over their lives, and finally spending half his life with a woman who’d try to glamorize his exploits and has mucked up the real story to this day; that he’d never have children; that he’d be remembered as a generous man who loved giving gifts and was devoted to reading; that dozens of books, TV shows and movies would be made about him, and his name would come to mean “Old West” all by itself.

He’d have probably laughed if he knew that when he died in Los Angeles on January 13, 1929, the Los Angeles Examiner would write: “He was 80 when death knocked; it found the old lion of Tombstone, as ever, ready. They were what might be called old acquaintances, having played hide-and-seek with one another all over the west for nearly sixty years.”

No, his days in Iowa were the days of a little boy—then a teen—who probably marked only Christmas and his birthday on March 19. The rainy day he was born in 1848, his father gave him the full name of his commanding officer from the Mexican War: Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp.

All that name came to mean was still far, far away. But then, so were the names Wichita and Dodge City and Tombstone, none of which existed in these years when Wyatt Earp was growing up.

The Earps of Pella

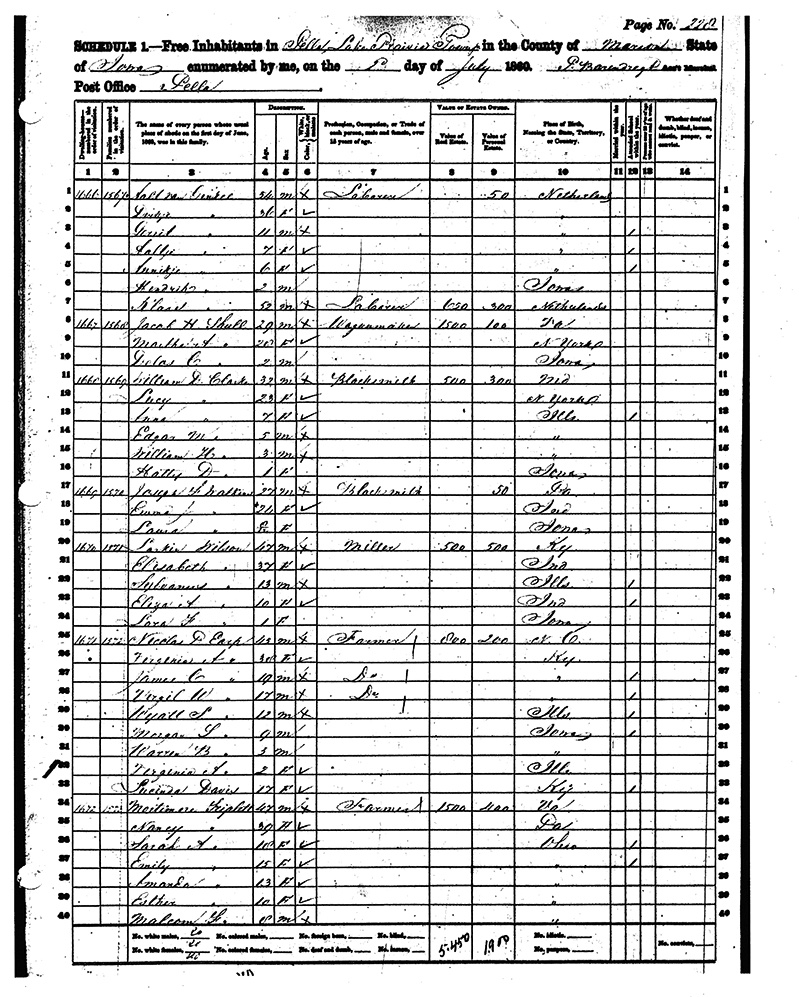

Wyatt Earp was two years old when his father brought the family to Pella in 1850. Big brother James was nine, Virgil was seven and sister Martha was five. Mother Virginia Ann gave birth to Morgan in 1851 and Warren in 1855. The family would tragically lose Martha in 1856.

The 1850 census lists Nicholas P. Earp as a cooper and a farmer, but he first supported the family as a steamboat captain for the Des Moines Steamboat Co. Starting in 1852, he bought “a considerable amount of farmland” northeast of Pella. One purchase included a “set of house logs, shingles, lumber, rails as well as logs still at the mill,” according to local archives. There’s no evidence he used the material to build a home, but it’s easy to surmise he had to, since the family was out there on the land and had to live somewhere.

Wyatt spent four years on that farm, near a town that eventually called itself “A Touch of Holland on the Prairie.” Pella was founded in 1847 by 800 immigrants fleeing religious persecution from The Netherlands—people wealthy enough to purchase the land and build a town with the motto: “In God Our Hope and Refuge.” (Only later generations could afford the tulips from the homeland that now give the town an annual Tulip Time Festival in May.)

The Earps left in 1854, moving back to their previous abode in Monmouth, Illinois, where they stayed for six years. Nicholas was busy politically, peeling off Democrats who were also antislavery to form a new political party known as Republicans. He was one of the organizers of a debate in the town square for the Illinois Senate candidates Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln. Democrat Douglas won the Senate race, but eventually lost to Lincoln in 1860—the first Republican candidate for president. The Earp family also grew, with the birth of Virginia Ann in 1858.

In 1859, Nicholas moved his family back to Pella, and eventually settled into a downtown row house. Wyatt was now 11. They stayed five years, until Nicholas led a wagon train to California in 1864 with three other Pella families.

There is no record of Wyatt Earp mentioning any of his two stints in this town, where workers wore wooden shoes and Dutch-born women still preferred long skirts, lace caps and aprons.

That doesn’t mean Pella is mute about the Earps. At least, not anymore.

“For years, people didn’t want to talk about the Earps living here,” says Valerie Van Kooten, executive director of the Pella Historical Society and Museums. “They felt it was not a good role model. Five years ago the house was in such bad shape, some said we should tear it down. But I thought we were sitting on a gold mine—we’re the only ones who can tell the story of Wyatt from age two to 16, and we should tell it the best way we can.”

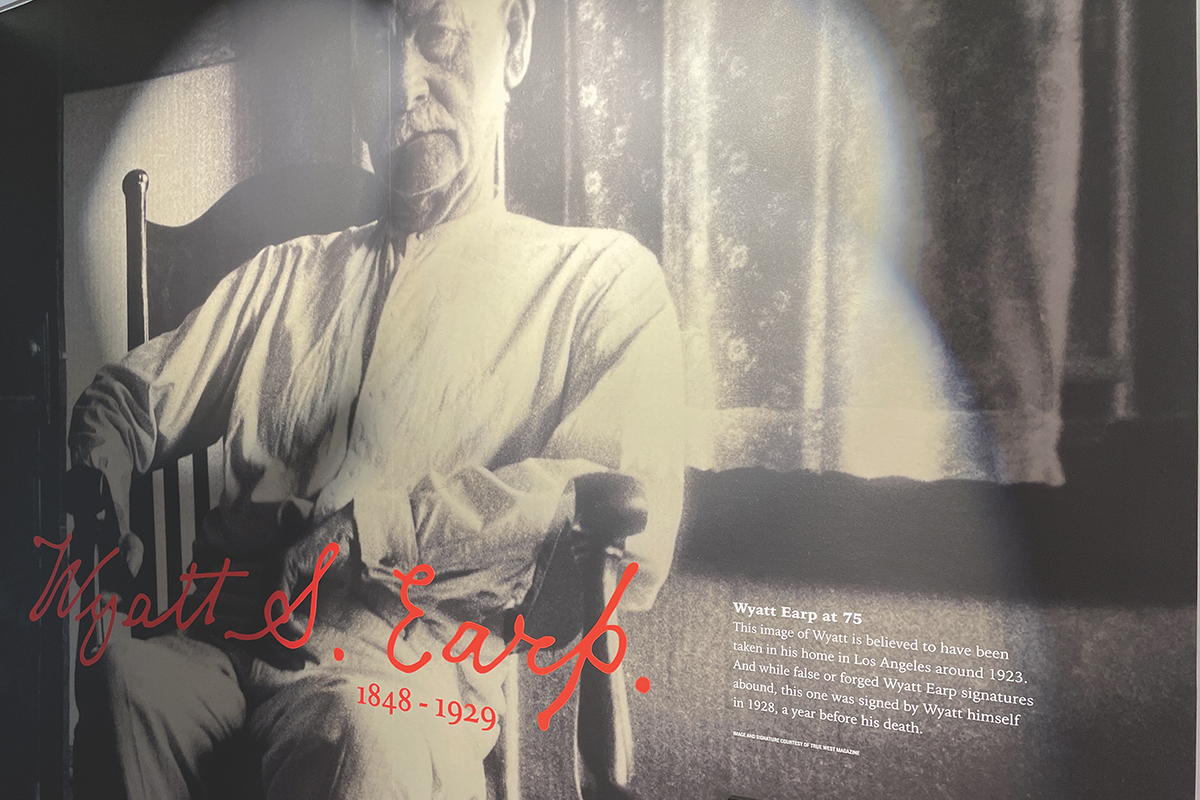

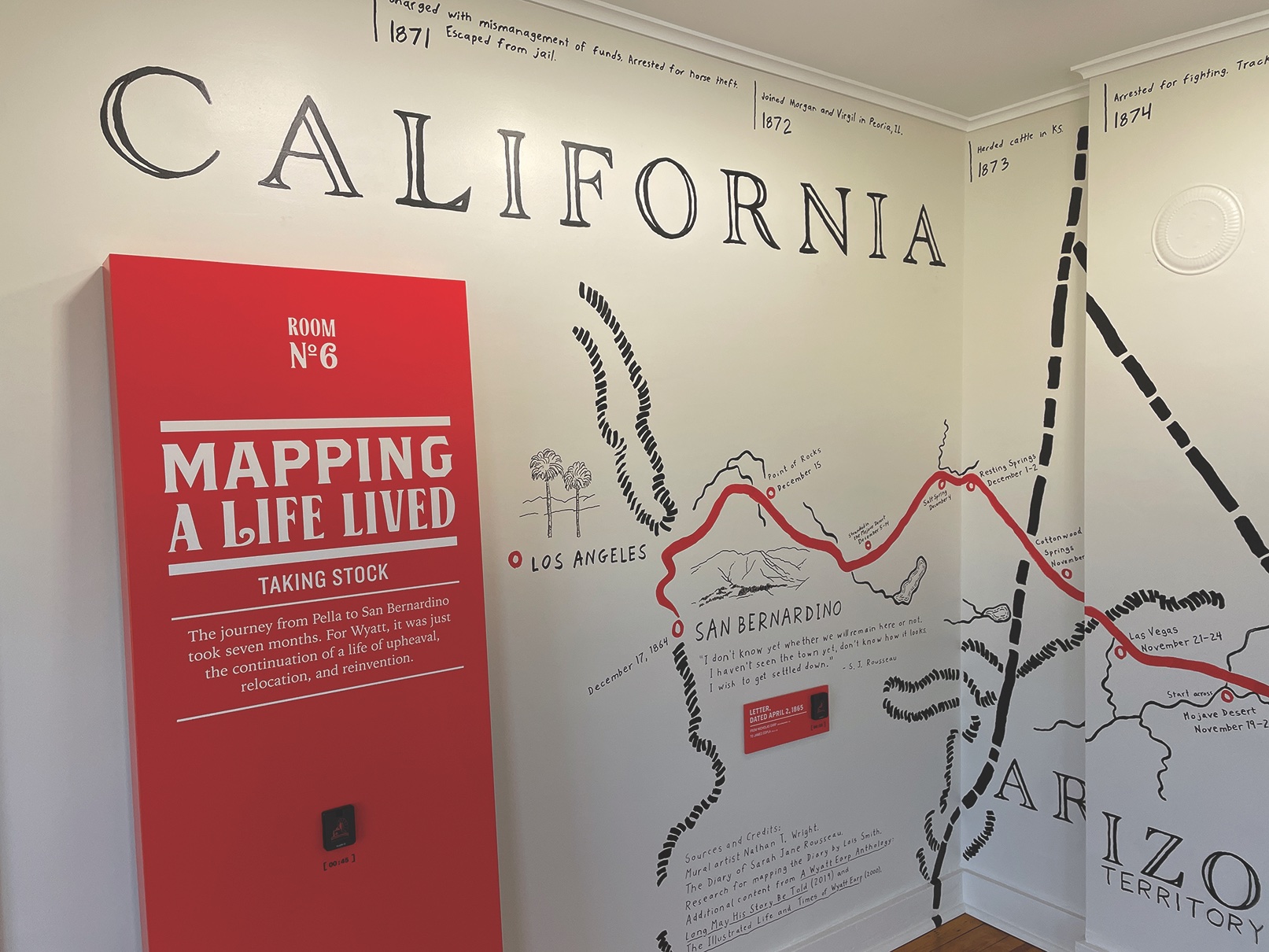

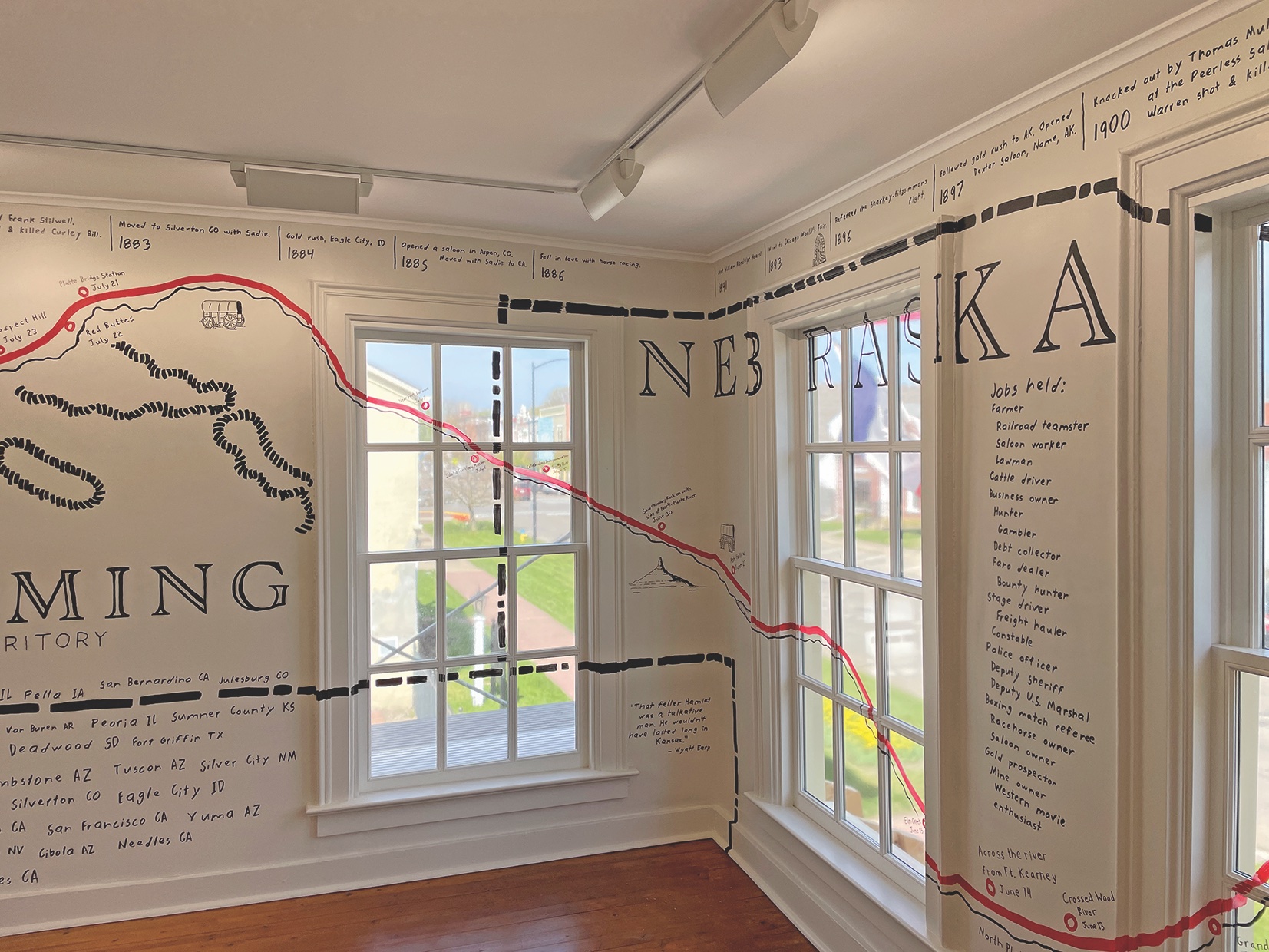

The Society has been hard at work on the project ever since, and now can proudly say it has not only totally restored the row house to its 1800s glory but has created new multimedia exhibits to capture the entire life of Wyatt Earp. Archivist Lois Smith notes it includes Pella during the Earp years, the Earp brothers in the Civil War, the three women in Wyatt’s life, the legend that grew around him, the wagon train trip to California when Wyatt was 16, and Wyatt as an old man.

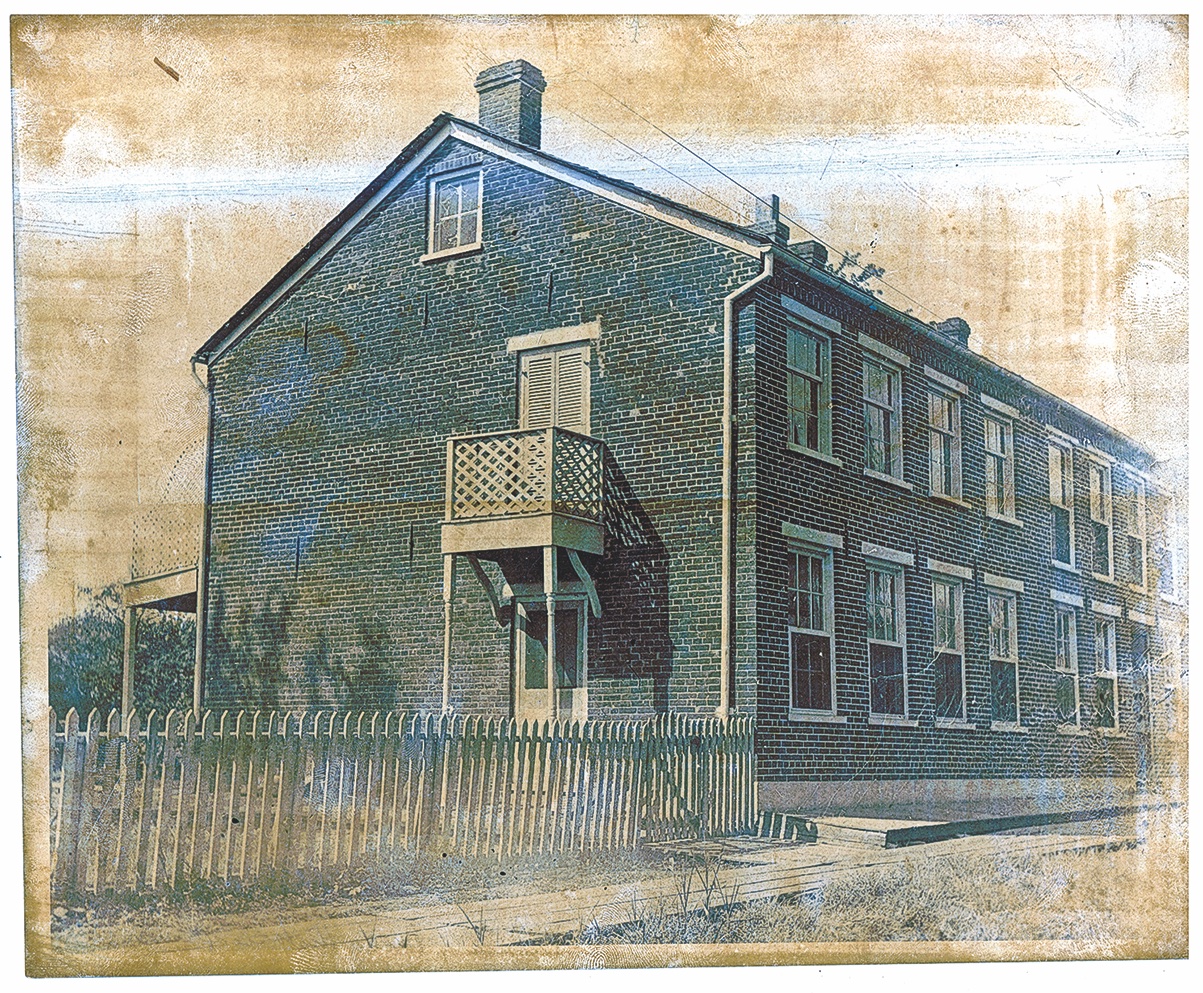

The Earp family lived in the first-floor apartment of a row house built by the Van Spanckeren brothers on Franklin Street near the center of town from 1861 until 1864. This is where, in 1861, Adelia was born in June and three-year-old Virginia died in October, while their father was an alderman on the Pella City Council. Nicholas was appointed town marshal in 1862, serving until he left with the wagon train.

The house, done in the 18th-century Dutch style of architecture, is an unusual look for the Midwest, and now is on the National Register of Historic Preservation. In 1966, it became the first official office of the Pella Historical Society, and a small Earp museum was started as part of the Historical Village. But there’s nothing “small” about the new museum, which officially opened in early May during the town’s annual Tulip Time Festival. Some Earp descendants surely attended, including Van Kooten’s daughter-in-law, who is related by marriage to the Lorenzo Earp side of the family that still lives in the Pella area.

Archivist Smith also agonizes that few records exist about young Wyatt, but says if he went to school here, he’d only have had a couple blocks’ walk to the town’s first brick, two-story Park School. She suspects he enjoyed the traditional Fourth of July celebrations that were popular throughout the nation. But records do tell of Wyatt’s thirst to fight in the Civil War. His older brothers all went off to fight on the Union side, including Nicholas’s son from an earlier marriage, Newton. Wyatt watched as 13-year-old Tommy Cox of Pella joined up as a drummer boy, and decided he could go too, after all, he was 25 days into his 13th year when war broke out. But his father and mother declared he was too young to go, and even though Wyatt ran away to join up a couple times, his father always apprehended him and brought him home.

Nicholas put Wyatt in charge of one of the farms, expecting him to get help from younger Morgan and Warren. Wyatt learned he wasn’t a farmer. It paled in comparison to the action he imagined his brothers facing. But in the end he stayed put, because the strongest tie was to family.

And it was these years, mainly in Pella, that “family” became defined in the heart and soul of Wyatt Earp.

It would be nice to know more about his life in those years—the few shreds we have seem too pitiful, considering the volumes we have about his life after these years.

But thanks to the Pella Historical Society, the story we can piece together is being told.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written three true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.

Author’s Note:

I want to thank the experts who so generously shared their time and information with me in writing this column: Valerie Van Kooten, executive director of the Pella Historical Society; Lois Smith, archivist of the Pella Historical Society; historian and journalist Nicholas R. Cataldo, an authority on the Earp family in California; Dr. William Urban, the Lee L. Morgan Professor of History and International Studies at Monmouth College, Illinois; historian and award-winning columnist Scott Dyke of Green Valley, Arizona; Wyatt Earp author Casey Tefertiller, and historian and True West Executive Editor Bob Boze Bell.