The Man who Saved 100 Nations

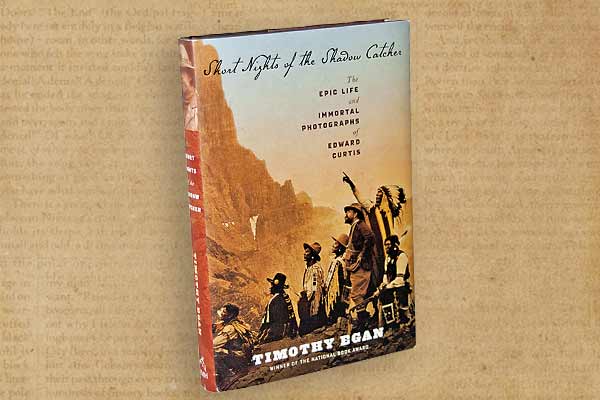

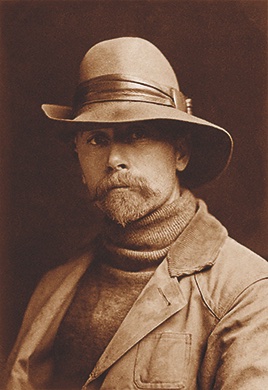

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) was a 19th-century Western pioneer and entrepreneur, known for his photography, ethnography, writing, filmmaking, and even gold-prospecting and patents. His story is filled with courage, character and determination, and an understanding that life is more than survival. From the 1890s on, Curtis took thousands of photographs of Indigenous people across the American West and produced his monumental work The North American Indian (1907-1930), a 20-volume publication illustrated with photographs and text. Curtis’s project became the largest anthropological enterprise ever undertaken in the U.S. and was supported by Theodore Roosevelt and funded in part by John Pierpont Morgan.

National Portrait Gallery

“Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis” offers Scottsdale’s Museum of the West’s guests an opportunity to view the breadth and depth of Curtis’s work, artistry, photographic techniques and lifetime achievements. Featuring iconic and rarely seen images, this exhibition includes the 20 volumes of The North American Indian, original photogravures and copper plates, rare goldtones or Curt-Tones, platinum prints, silver gelatins, cyanotypes, glass-plate negatives and ephemera. Visitors will hear recordings selected from thousands that Curtis and his field team made as part of the ethnological data for The North American Indian project.

Curtis’s multifaceted contributions to the Western canon were declared important by his contemporaries, while today he is often viewed as a Renaissance man, having also contributed to the art and science of photography. His ability to adapt and persevere when faced with changing and difficult environments has long been appreciated. We hope the essence of Curtis’s gift as a maker of images will be more fully revealed, and that this exhibition offers a deep and rich understanding of his accomplishments as an artist, while paying homage to the crucial role of Native American participants in actualizing this iconic body of work.

“Light and Legacy,” featured in the Halle Foundation Great Hall and the Pulliam Fine Arts Gallery, opens to the public on October 19, 2021. The Curtis exhibition is sponsored by the Peterson Family; Charles F., Jennifer E., and John U. Sands; Scottsdale Art Auction; and the City of Scottsdale and its Tourism Development Commission.

—Tricia Loscher

Shadow Catcher: Apache and Navajo

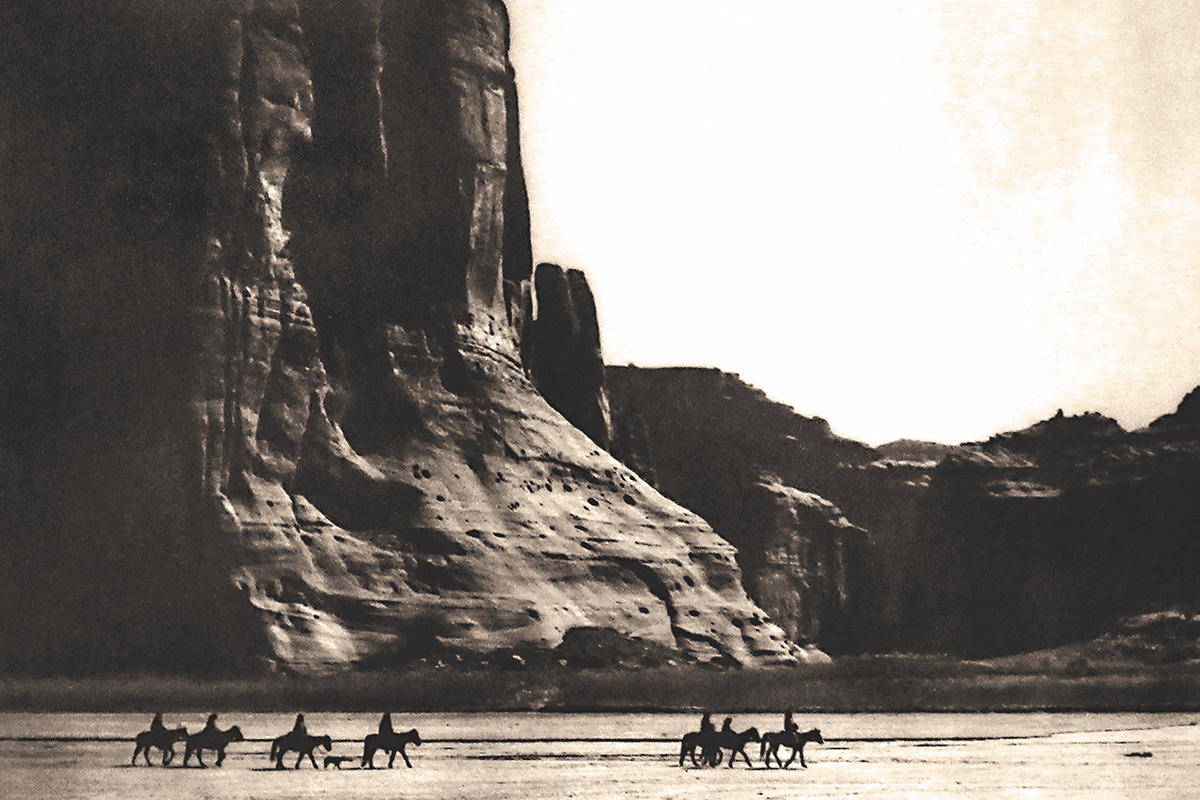

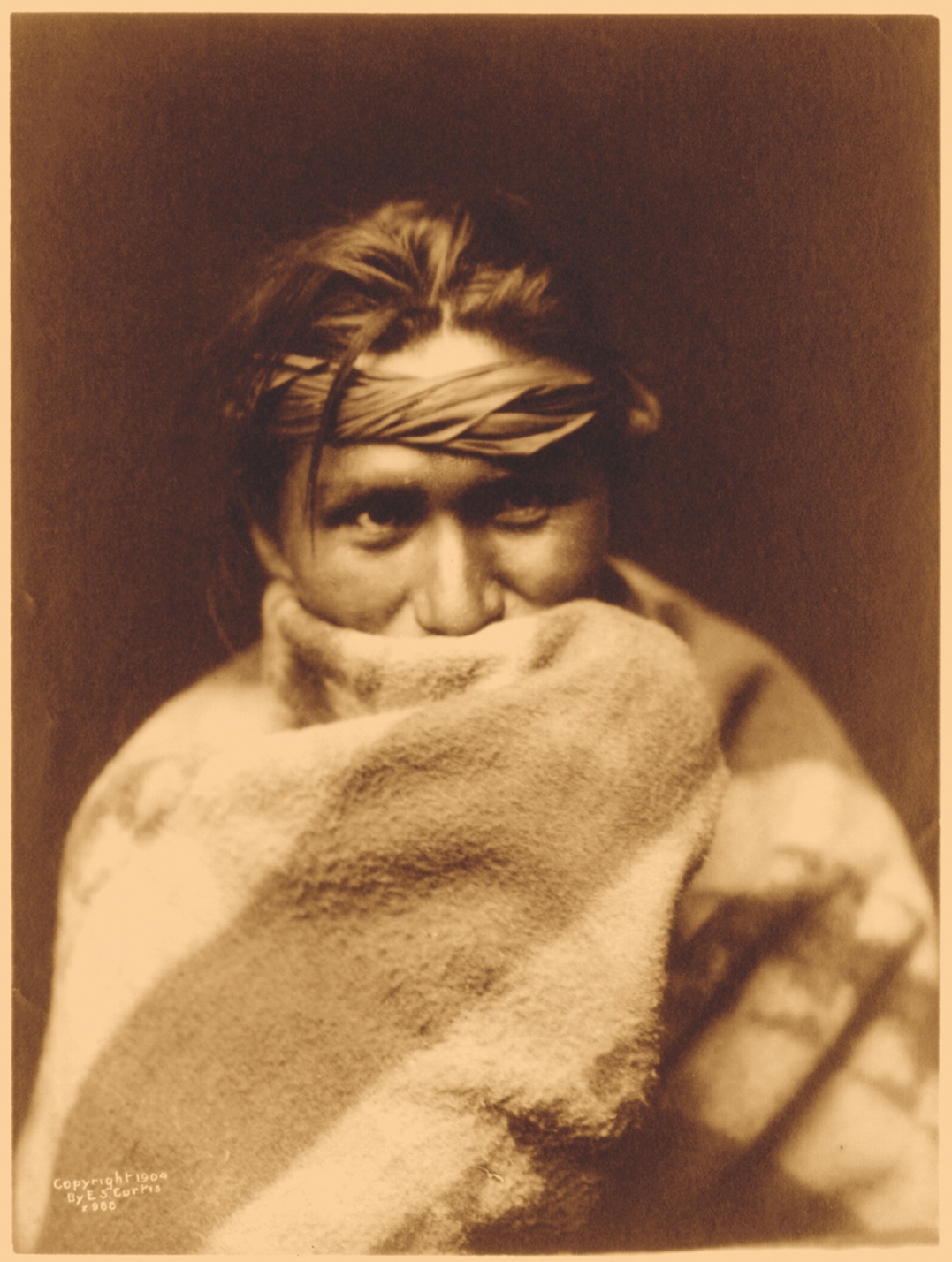

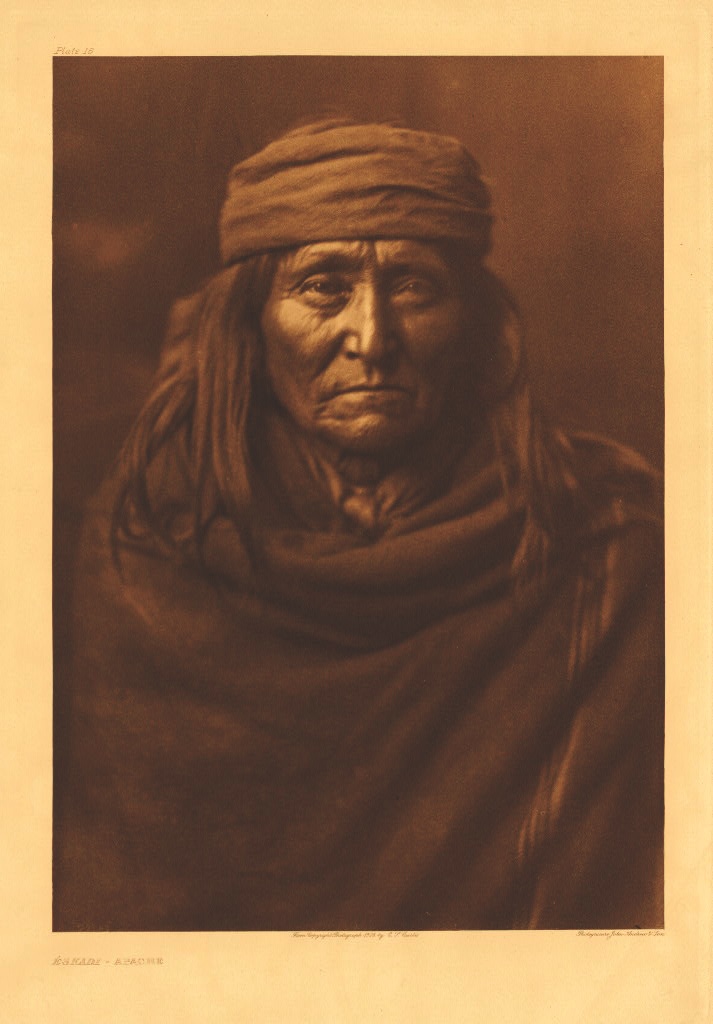

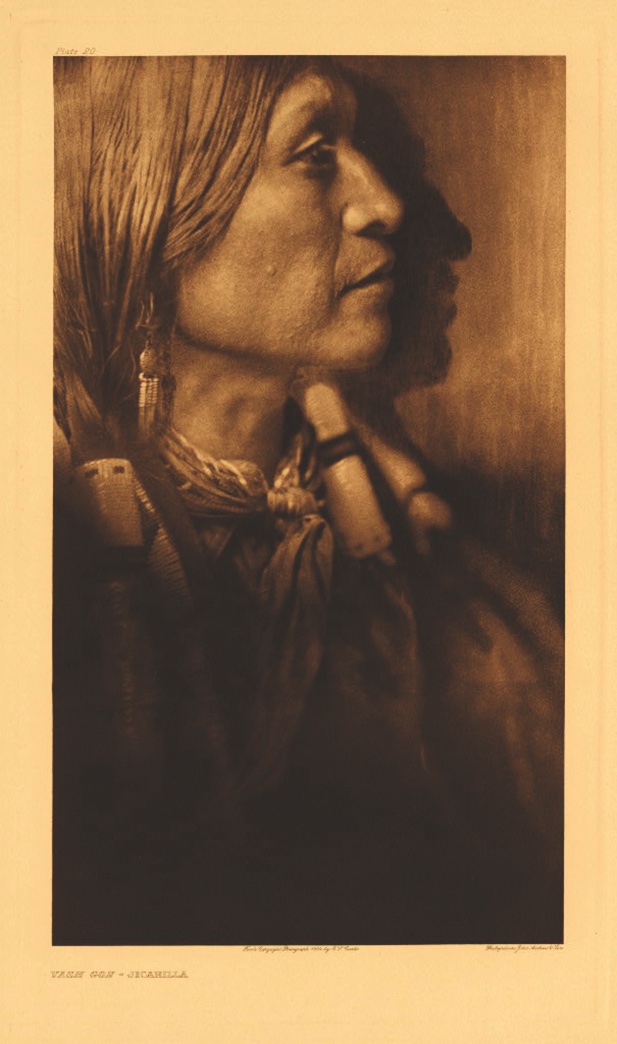

Edward Curtis commenced his ambitious project among the Apache, Jicarilla, and Navajo people. Some of his most celebrated and reproduced images come from this first volume, Cañon de Chelly–Navaho and The Vanishing Race–Navaho, the first image in the series, among them. Still, another image, later in the portfolio, Out of the Darkness–Navaho, is almost a film clip of Vanishing Race run in reverse. Curtis connected Navajos and Apaches through common aspects of their languages and contradicted the prevailing view of Apaches as primitive and warlike. Instead, his imagery and text paint these people as infinitely resourceful, fiercely loyal, devoutly religious, artistic storytellers. In photographs such as Apache Medicine Man, Curtis’s painterly understanding of light, combined with his darkroom skill, sculpts the figure out of the surrounding darkness, suggesting the longevity and sacredness of the medicine man’s ritual with finely drawn subtlety.

—Portfolio essays by James D. Balestrieri

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

Courtesy Library of Congress (1904)

Volume 1, Portfolio plate 16 (1903)

Volume 1, Facing page 94 (1904)

Volume 1, Portfolio 1 plate 20 (1904)

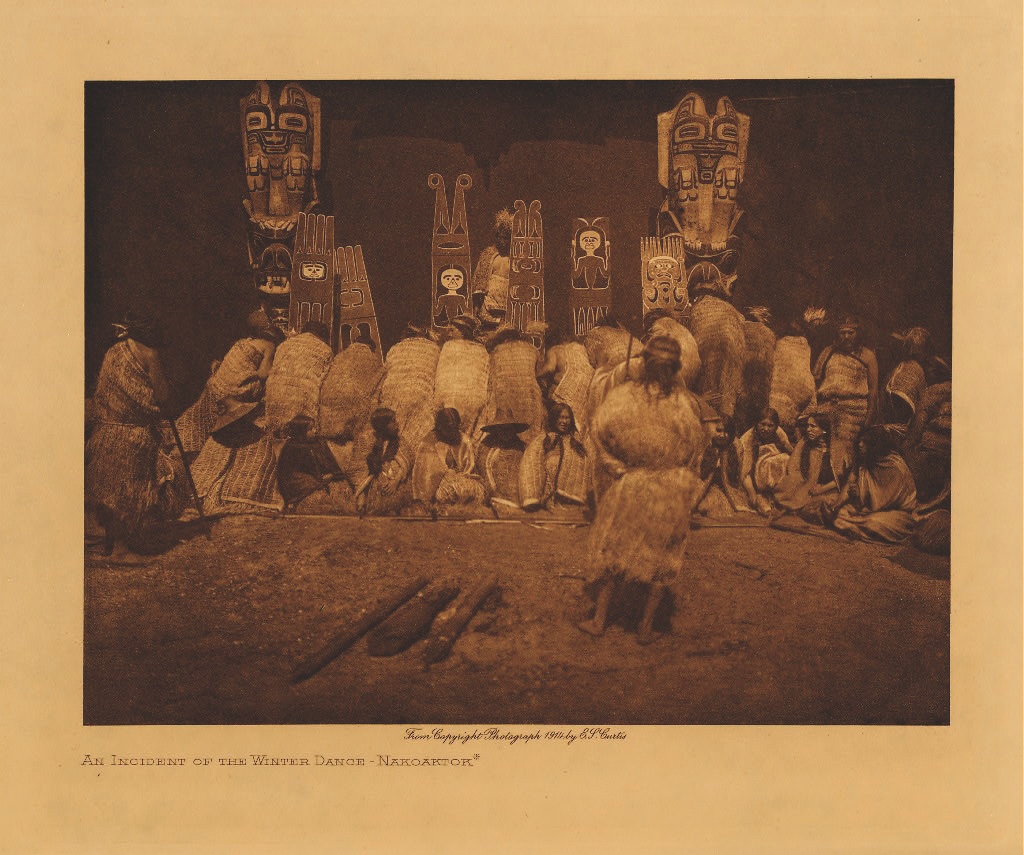

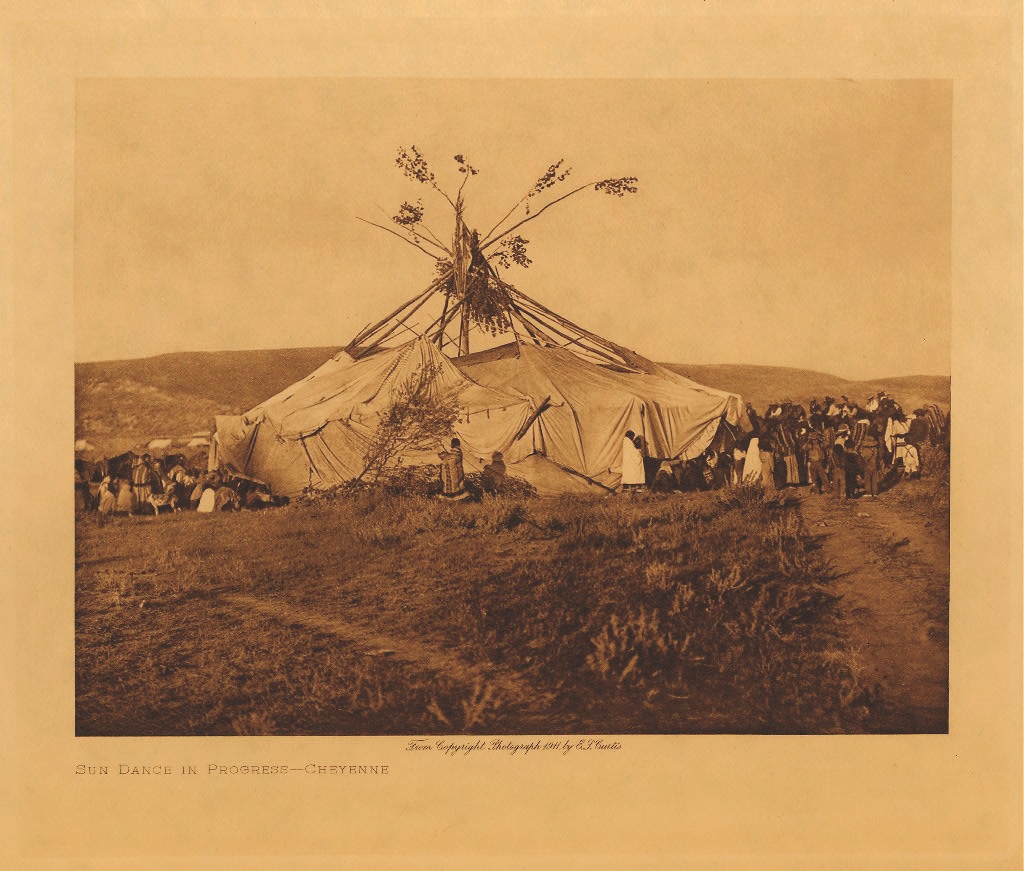

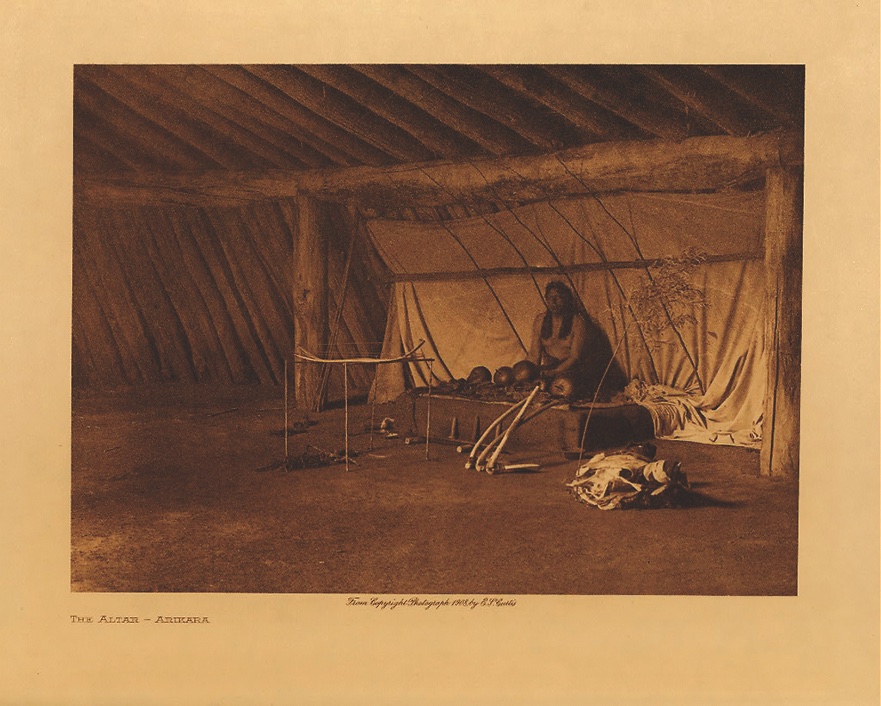

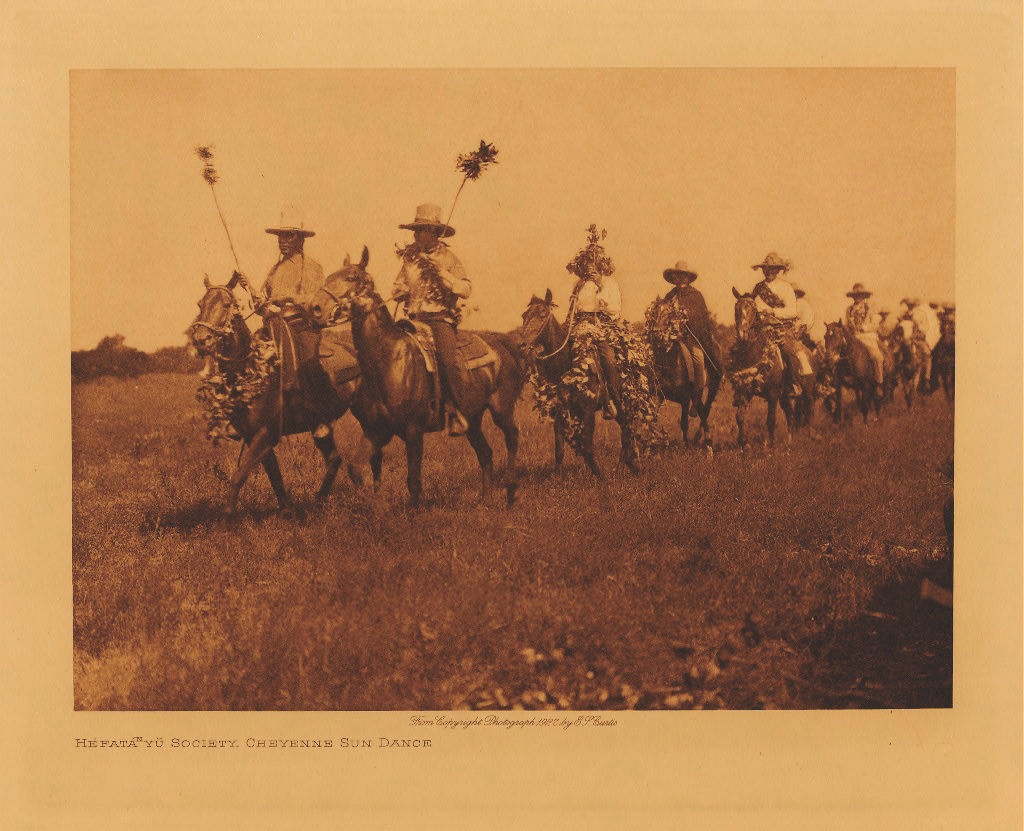

Shadow Catcher: The Ceremonies

Photographs of ceremonies lead us to the recordings of songs, the lists of words, the stories set down—aspects of Curtis’s work that are not summed up in the images you see here but are nevertheless crucial to understanding the scope of his endeavor. “Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis” at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West is one of the first exhibitions to combine Curtis’s visual artistry with recordings of his actual documentation of Indigenous languages. Curtis spent a great deal of time living among the peoples you see here, earning their trust. As he wrote in a letter late in his life, he tried to work “with Indians,” not “at them,” as he felt other anthropologists and ethnographers did.

Volume 5, Facing page 74 (1908)

Volume 10, Facing page 210 (1914)

Volume 6, Facing page 128 (1910)

Volume 3, Portfolio plate 91 (1907)

Volume 5, Facing page 68 (1908)

Volume 19, Facing page 114 (1927)

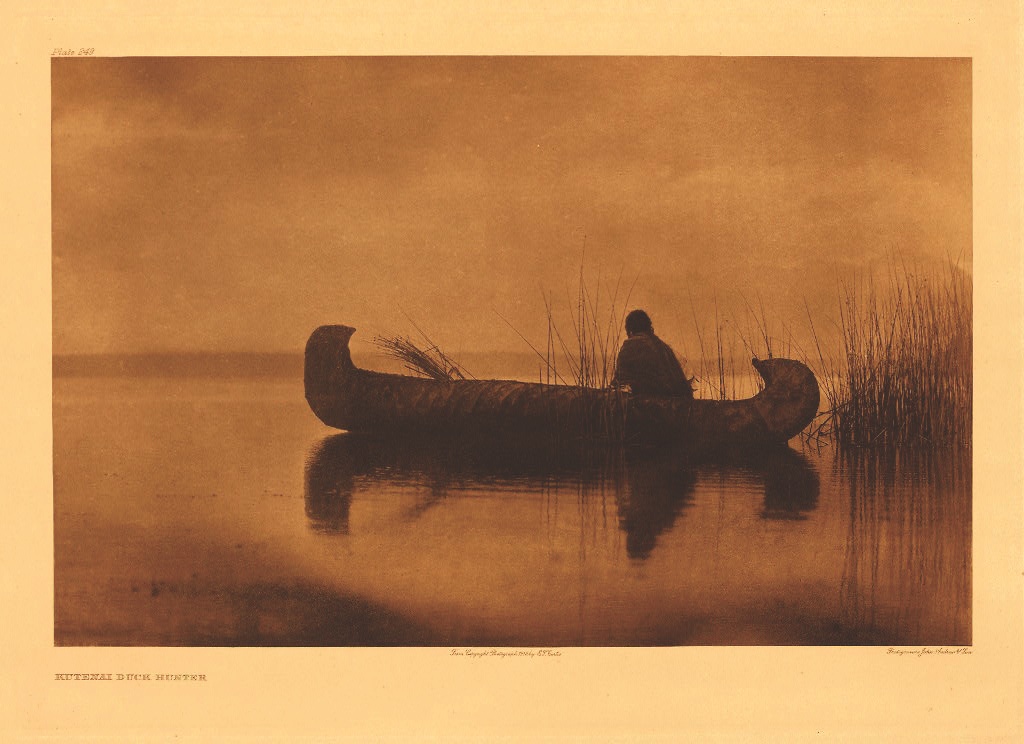

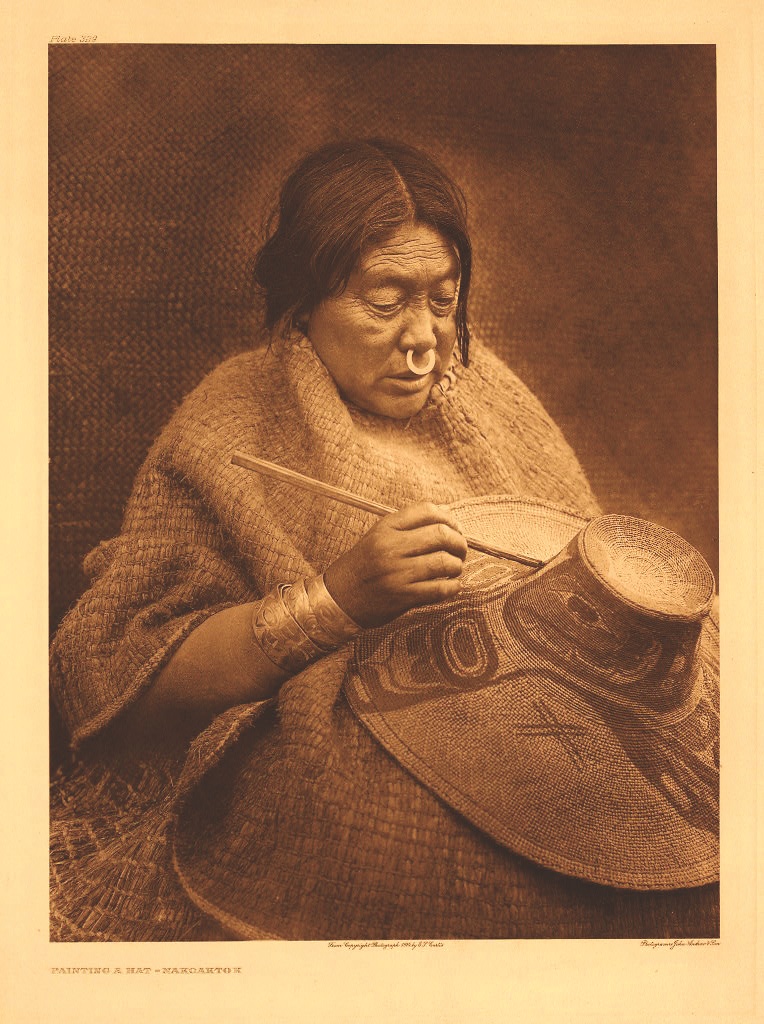

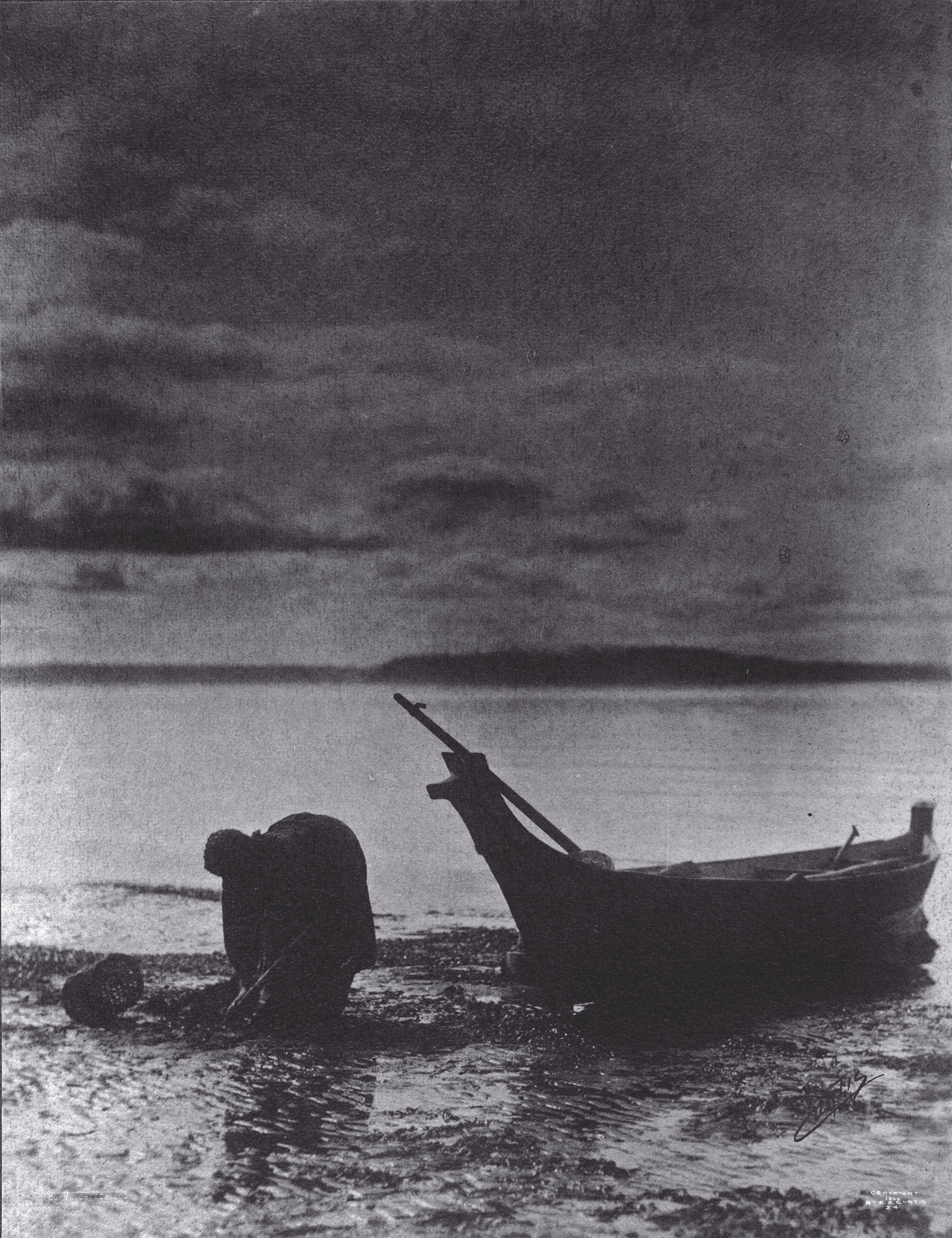

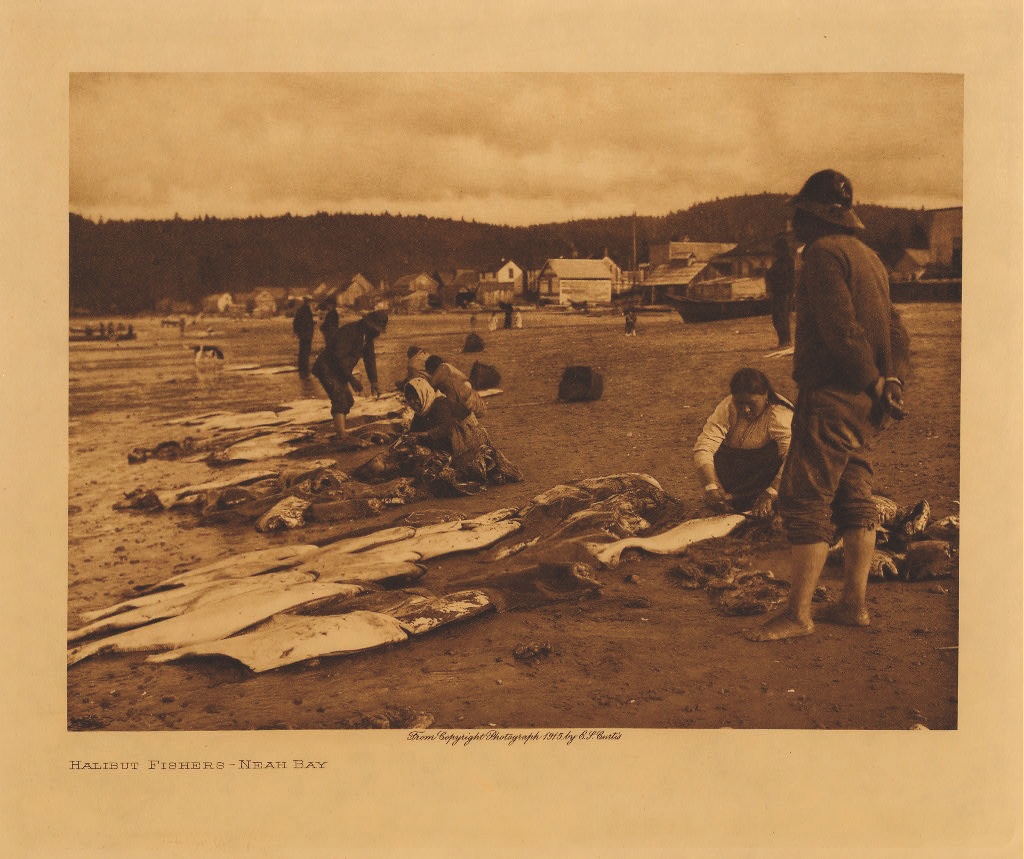

Shadow Catcher: The Northwest

The Pacific Northwest, Seattle specifically, is where the story of Edward Sheriff Curtis begins. He had a successful photography studio and a reputation as an up-and-comer in society when he had a chance meeting and opportunity to photograph Princess Angeline, the last daughter of Chief Seattle, reduced to digging clams on the beach. Curtis photographed Chief Joseph, who was brought to Seattle to watch a college football game—a contest that made no sense to him—and to give a speech in which he communicated his exhaustion and resentment at having been paraded around like a sideshow exhibit for years. As an expert climber and guide, Curtis rescued a Mt. Rainier climbing party that included George Bird Grinnell, who would launch the photographer into his all-consuming project, The North American Indian.

Volume 7, Portfolio plate 249 (1910)

Volume 10, Portfolio plate 329 (1914)

Volume 8, Facing page 6 (1910)

Volume 10, Portfolio plate 333 (1914)

Volume 9, Portfolio plate 317 (1900)

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

Volume 11, Facing page 76 (1915)

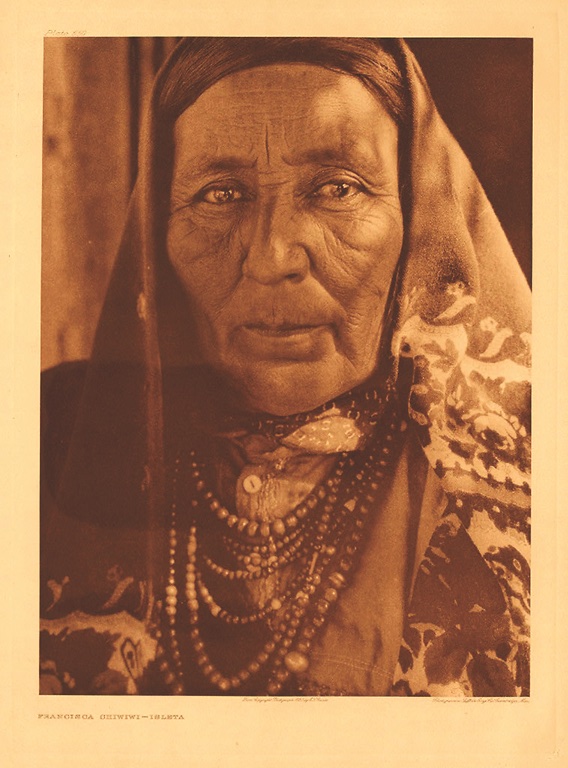

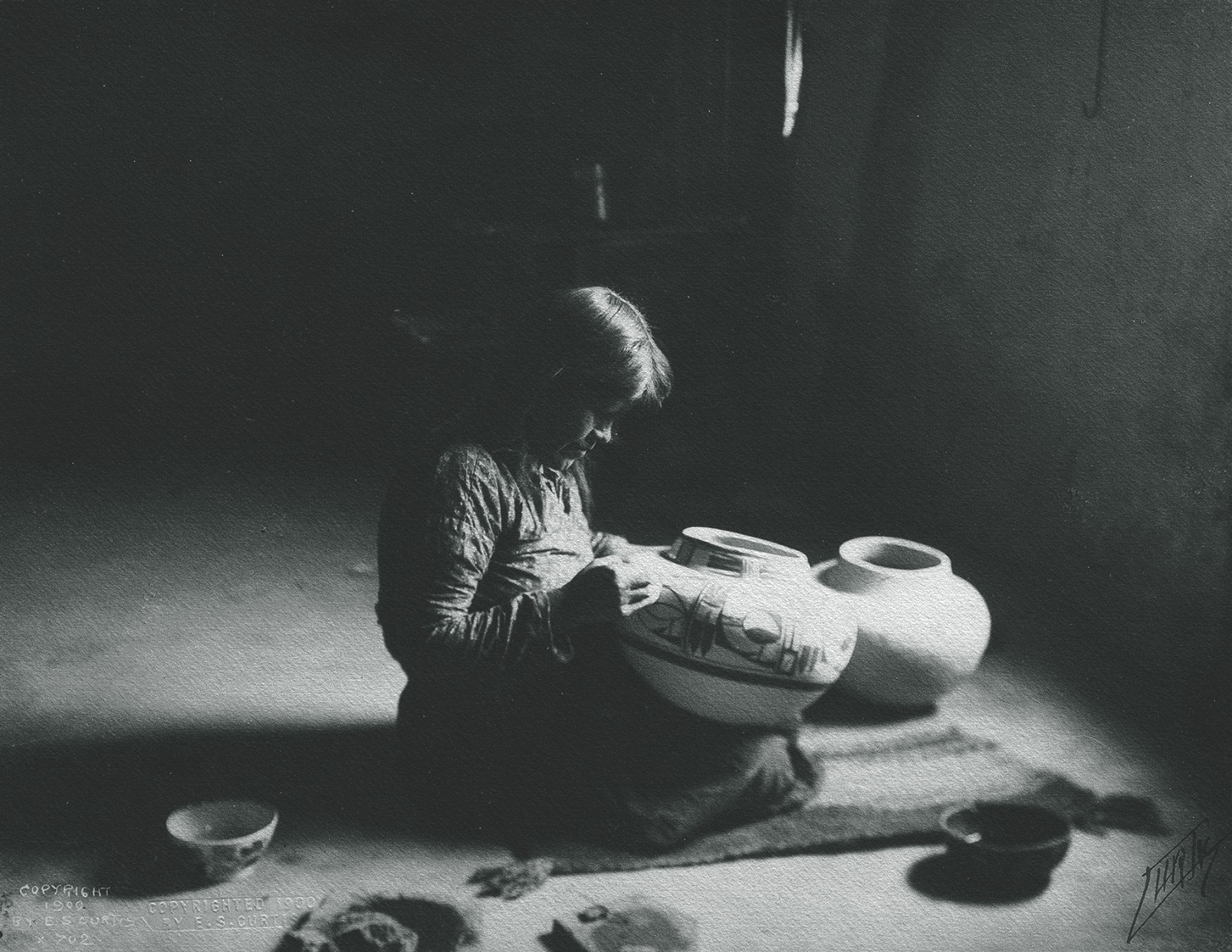

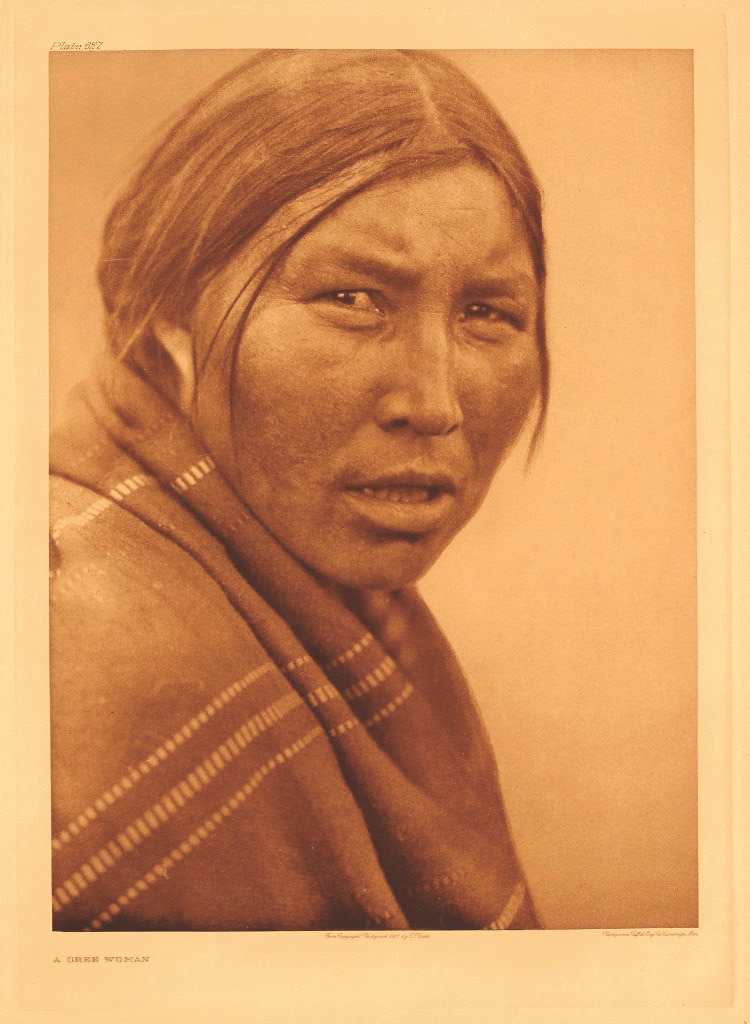

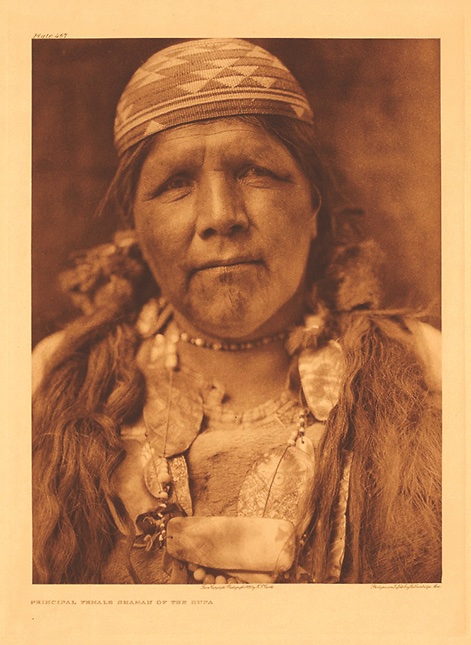

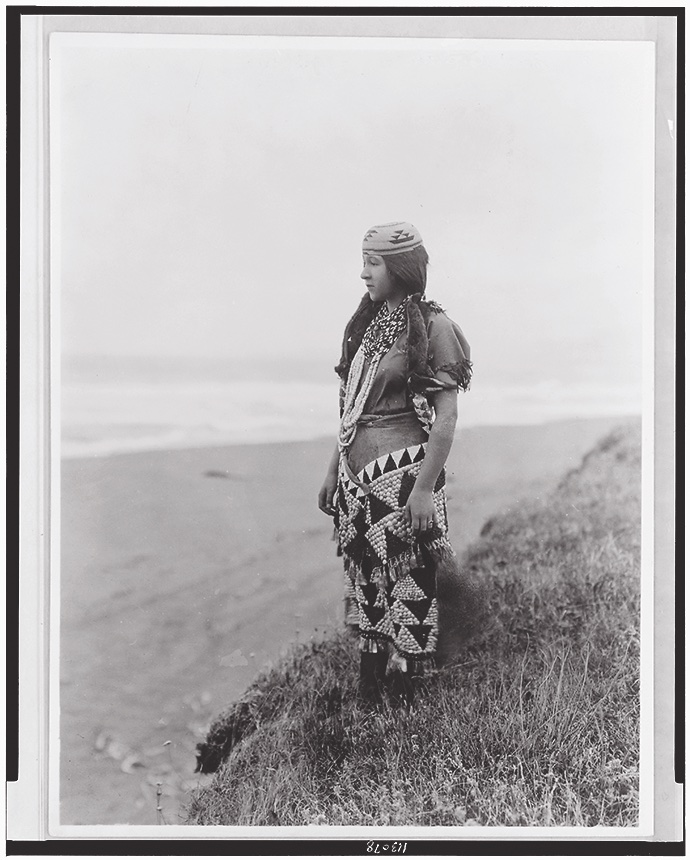

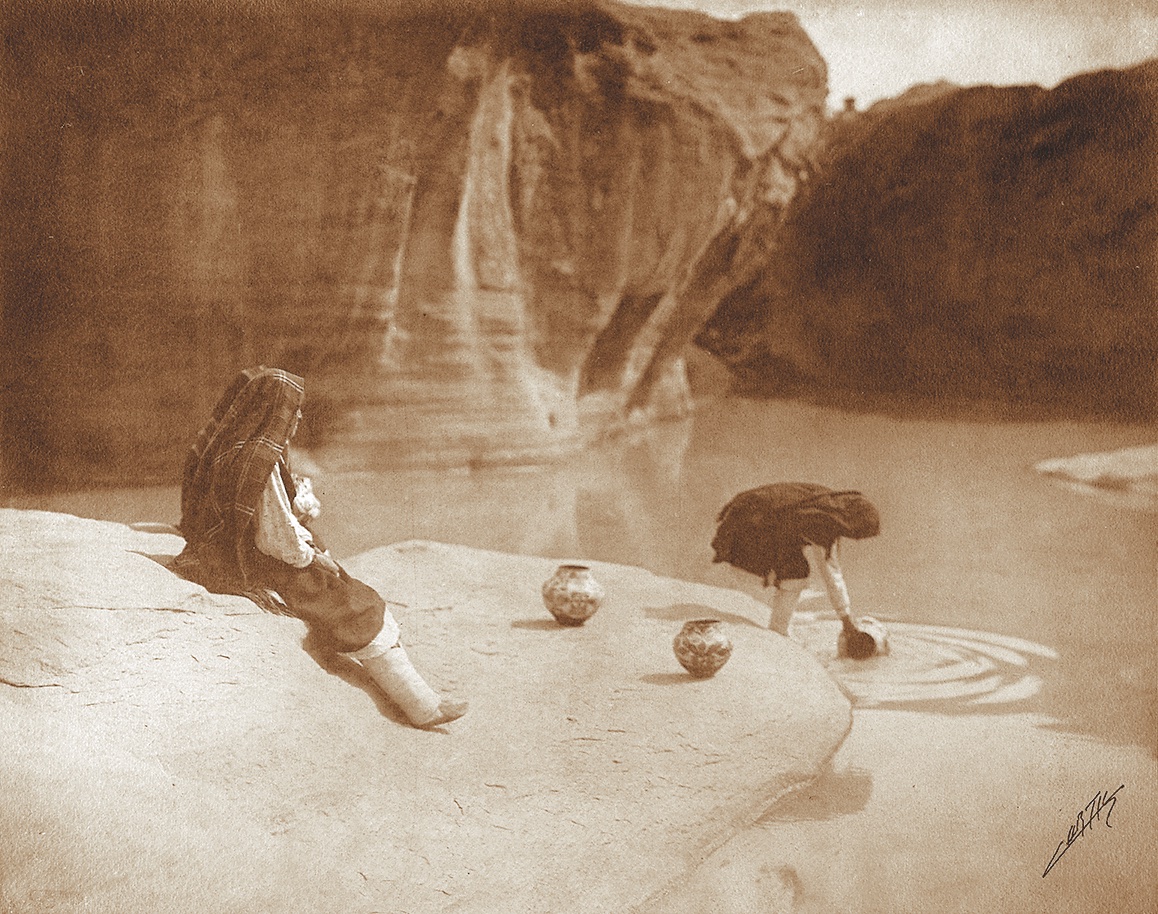

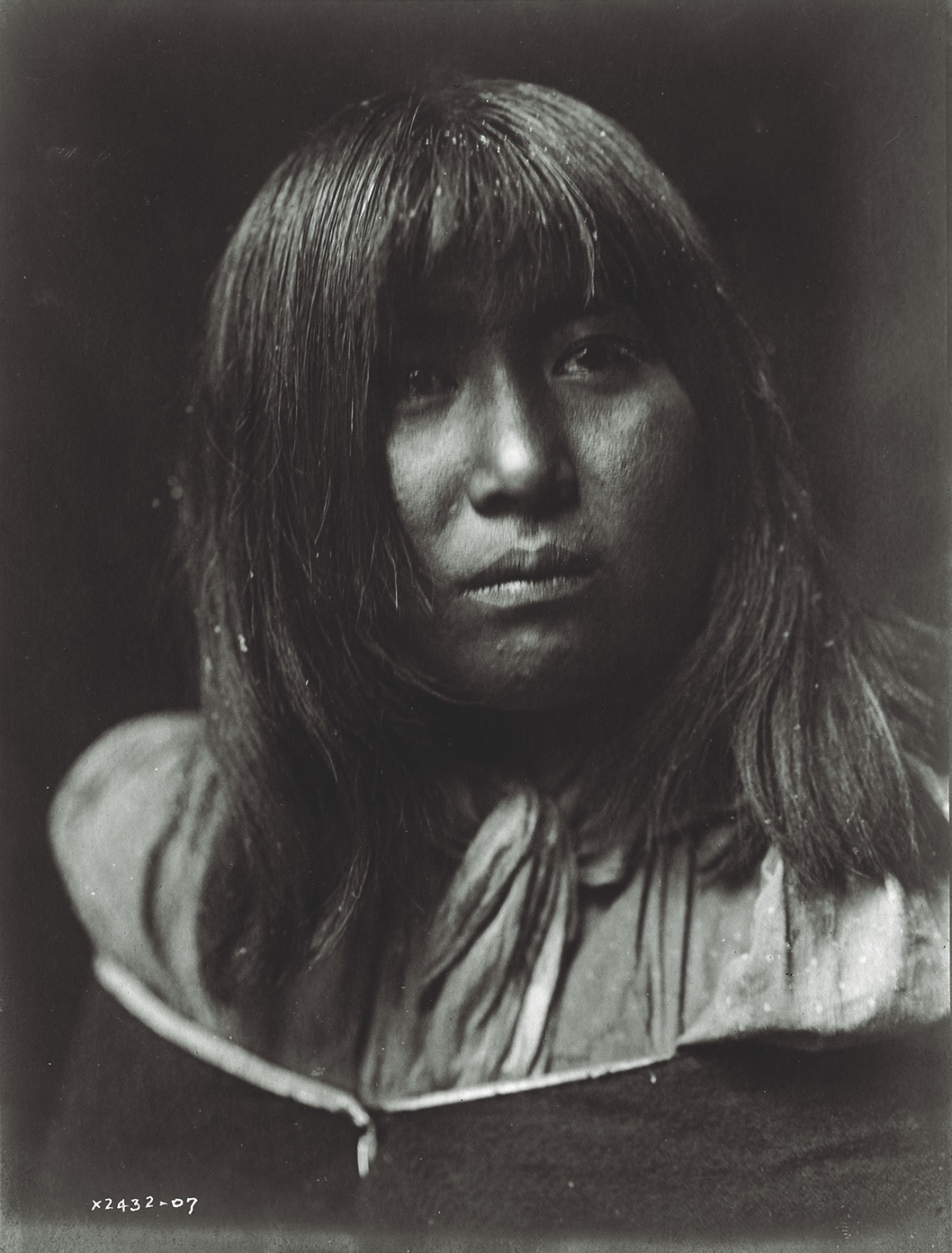

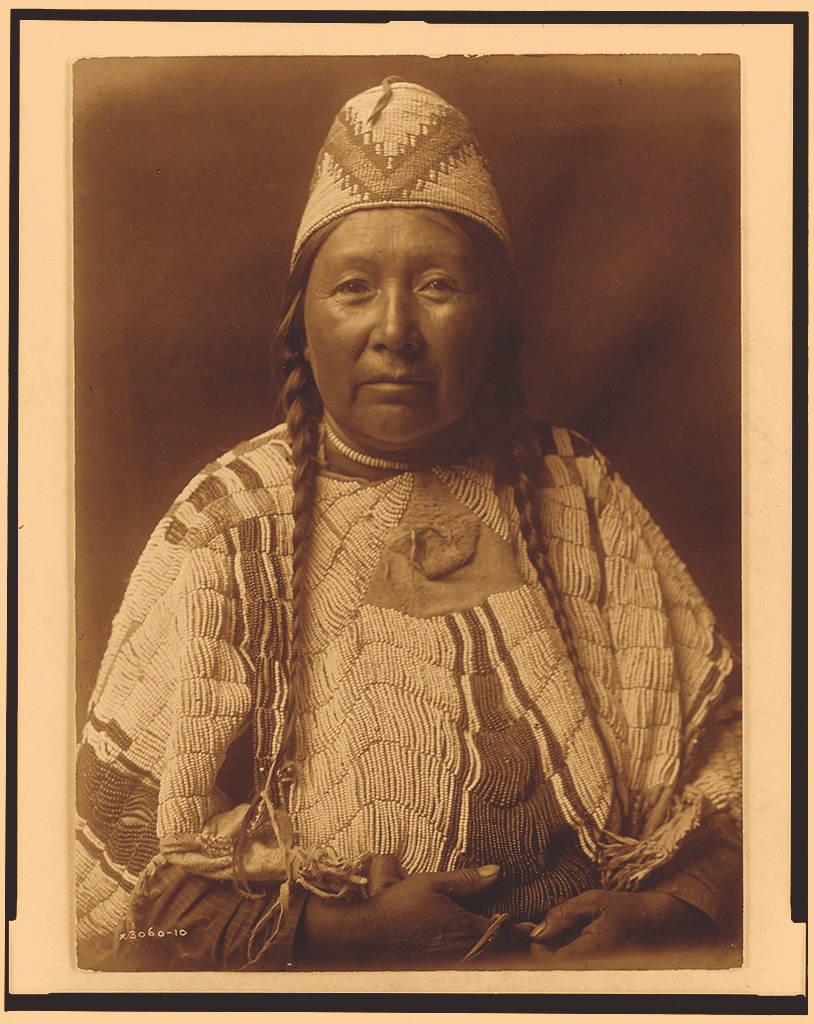

Shadow Catcher: The Women

Edward Curtis’s photographs of women on these pages express their defiance, artistry and tenacity. Their curiosity and frankness shine through. Curtis photographed girls, young women, mothers and the elderly, presenting the wide range of styles of dress and adornment that were—and are—found among Indigenous peoples. Of the images seen here, three examples immediately present themselves. The Potter–Nampeyo, whose skill and creativity made her famous in her lifetime, works in this image on her “canvases of clay.” The young woman in Woman’s Primitive Dress–Tolowa possesses a confident allure that is anything but primitive—the long necklaces, puffy sleeves, low-hanging skirt and beaded skull cap place her out in front of the flappers of the 1920s as a woman to be reckoned with. By recording the name: Stsimaki (“Reluctant-to-bewoman”)–Blood, Curtis creates an impression that speaks to a Chipewayan resistance to gender norms.

Volume 12, Portfolio plate 416 (1921)

Volume 16, Portfolio plate 550 (1925)

Platinum Photograph Courtesy The Tim Peterson Family Collection

Volume 16, Portfolio plate 548 (1905)

Volume 20, Portfolio plate 691 (1928)

Volume 9, Portfolio plate 314 (1899)

Volume 5, Portfolio plate 160 (1908)

Volume 18, Portfolio plate 627 (1926)

Volume 13, Portfolio plate 467 (1923)

Volume 13, Portfolio plate 461 (1923)

Courtesy Library of Congress

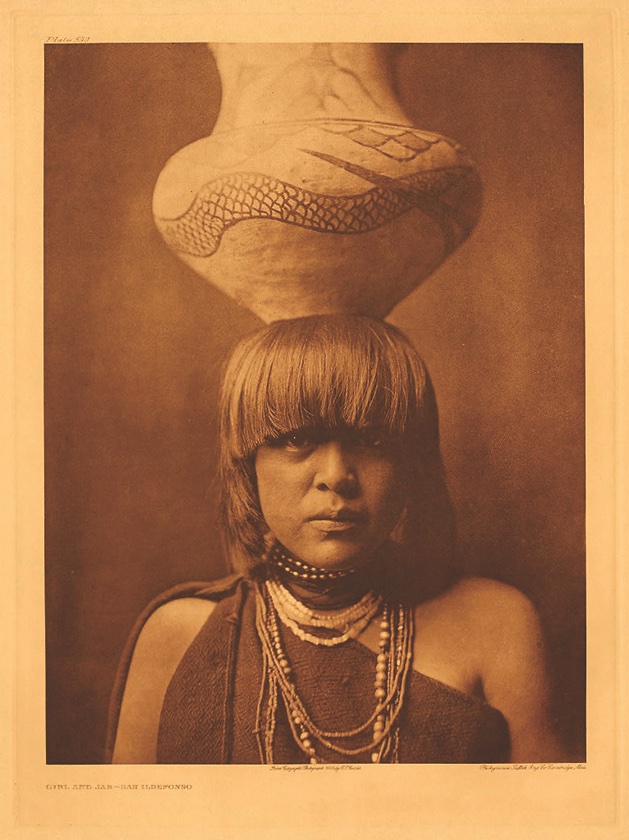

Shadow Catcher: The Pueblos

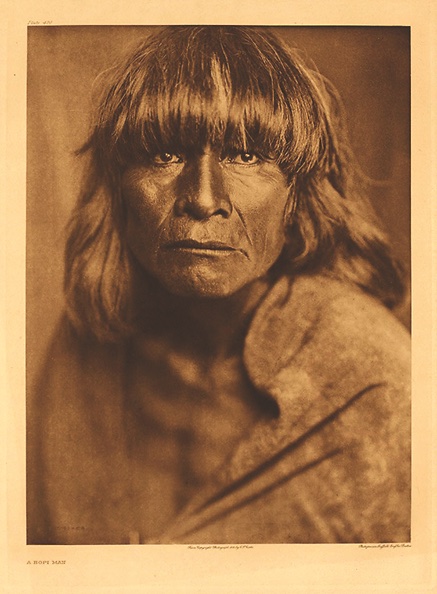

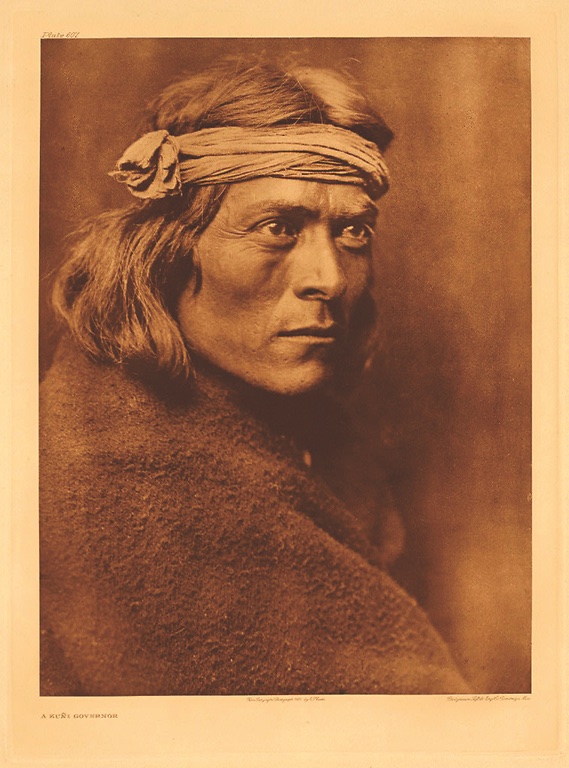

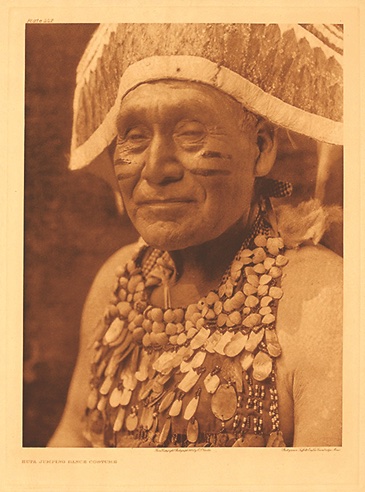

Drawn to the continuity of life on the Pueblos of Arizona and New Mexico and to the long development of their arts and spirituality, Curtis visited the Hopi, Zuni and New Mexican Pueblos. The Hopi volume, for example, is one of only two devoted to a single tribe. Curtis was fascinated by the mystery of the Hopi Snake Dance. After three years as a witness, he was at last invited to take part. The architecture of the Pueblos, the complex rituals of the Katsina Cult and the close bond between the people and the rhythms of the seasons all find their way onto Curtis’s glass plate negatives. Like many other artists, Curtis sought to capture the light that saturated these places. These volumes also feature some of Curtis’s most striking and artistic portraiture.

Volume 12, Portfolio plate 418 (1900)

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

Volume 17, Portfolio plate 590 (1905)

Volume 12, Portfolio plate 420 (1921)

Volume 12, Portfolio plate 432 (1906)

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

Volume 17, Portfolio plate 607 (1925)

Volume 16, Portfolio plate 571 (1904)

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

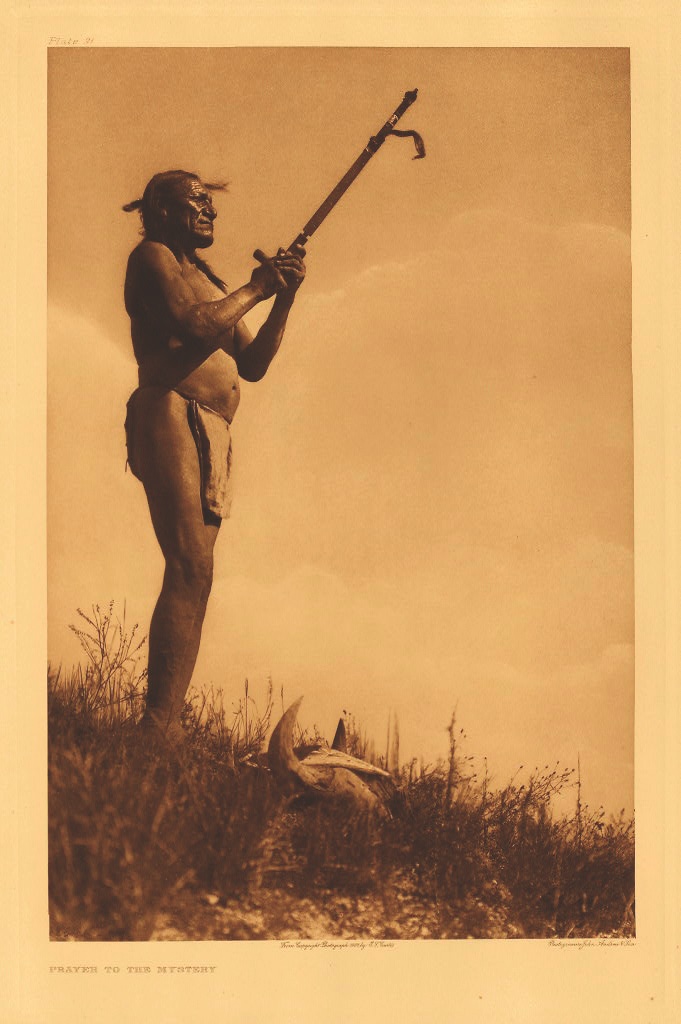

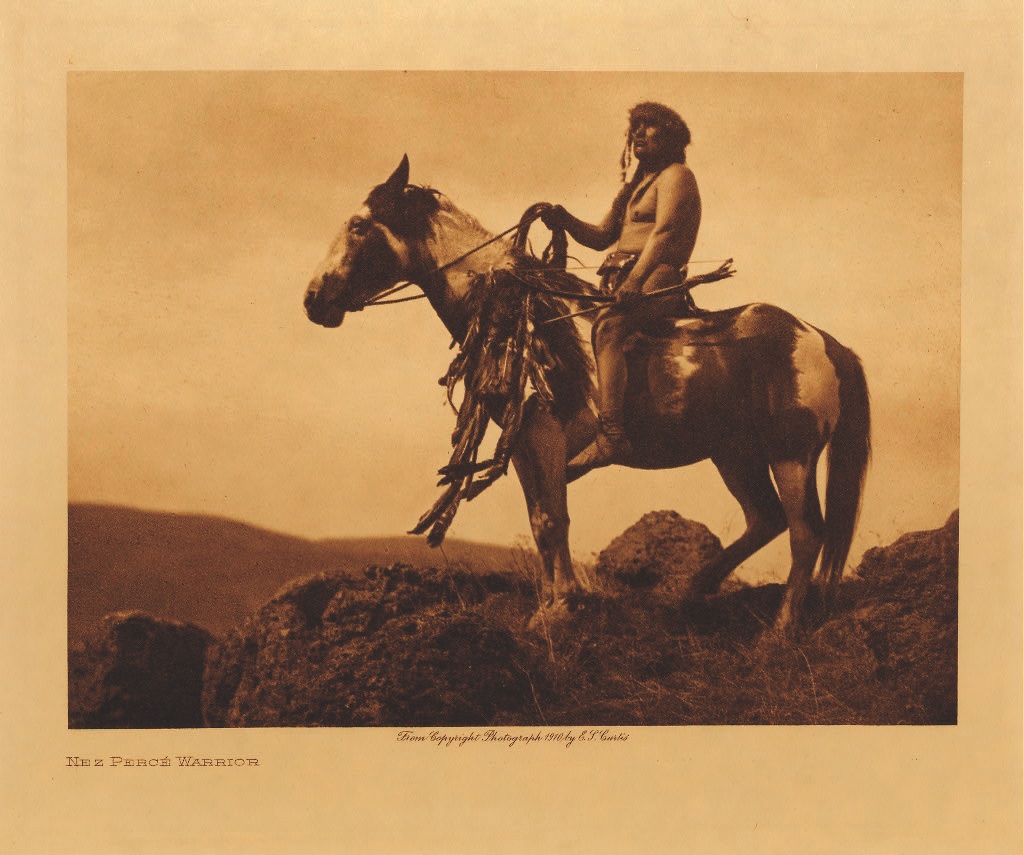

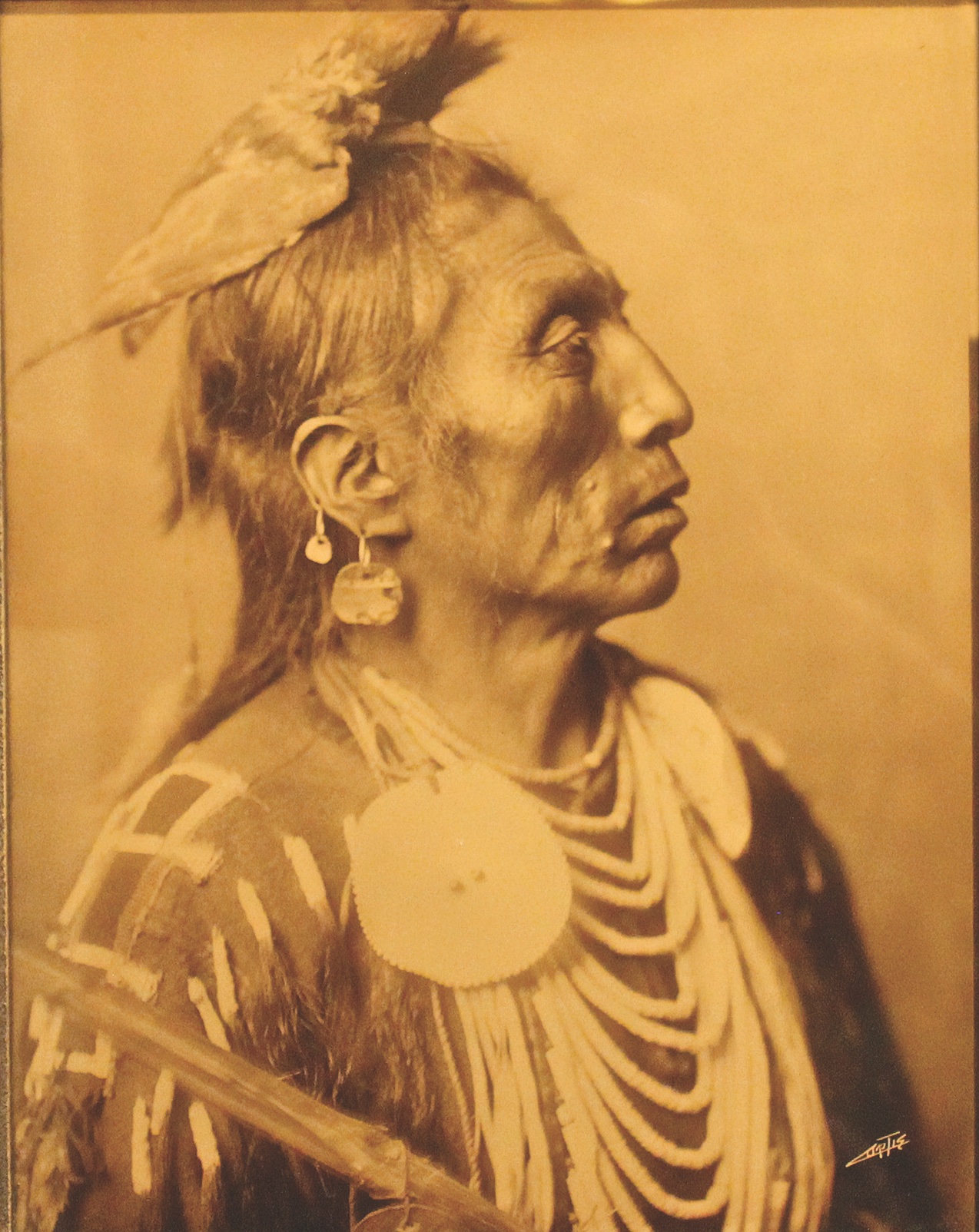

Shadow Catcher: Northern Plains

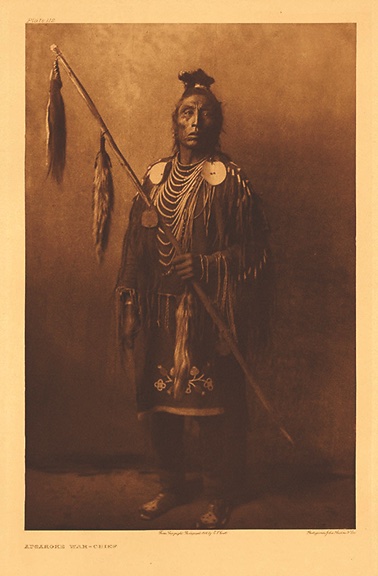

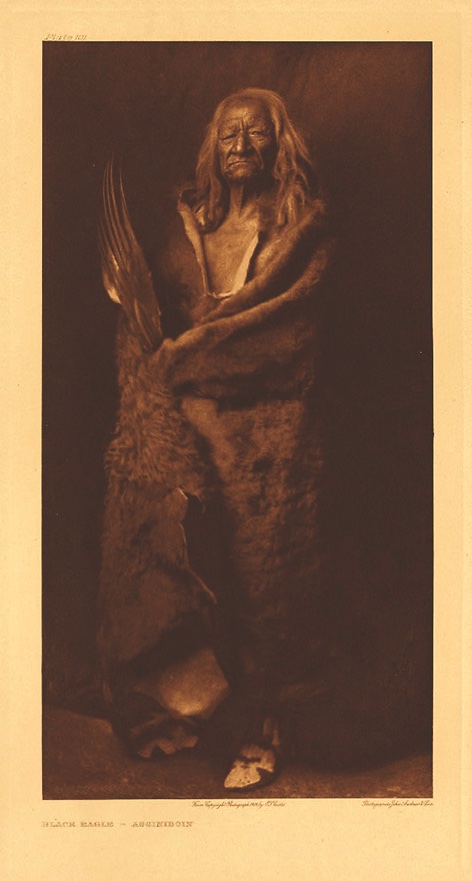

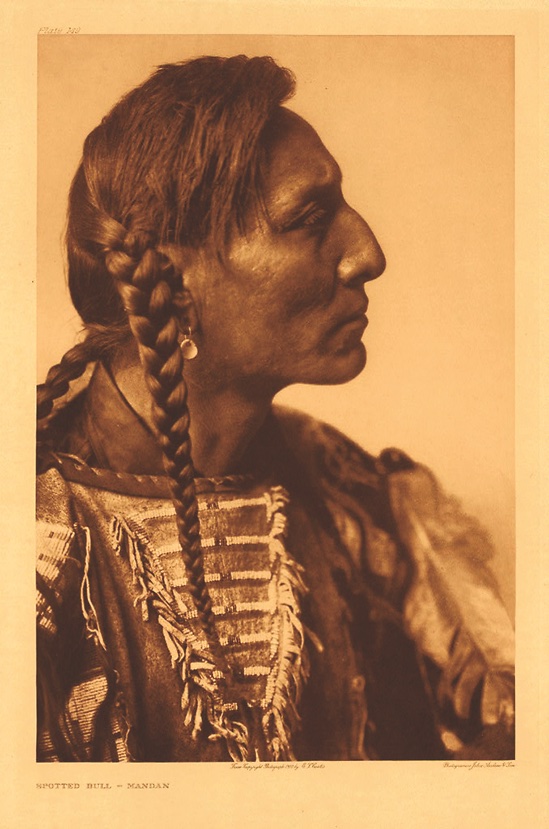

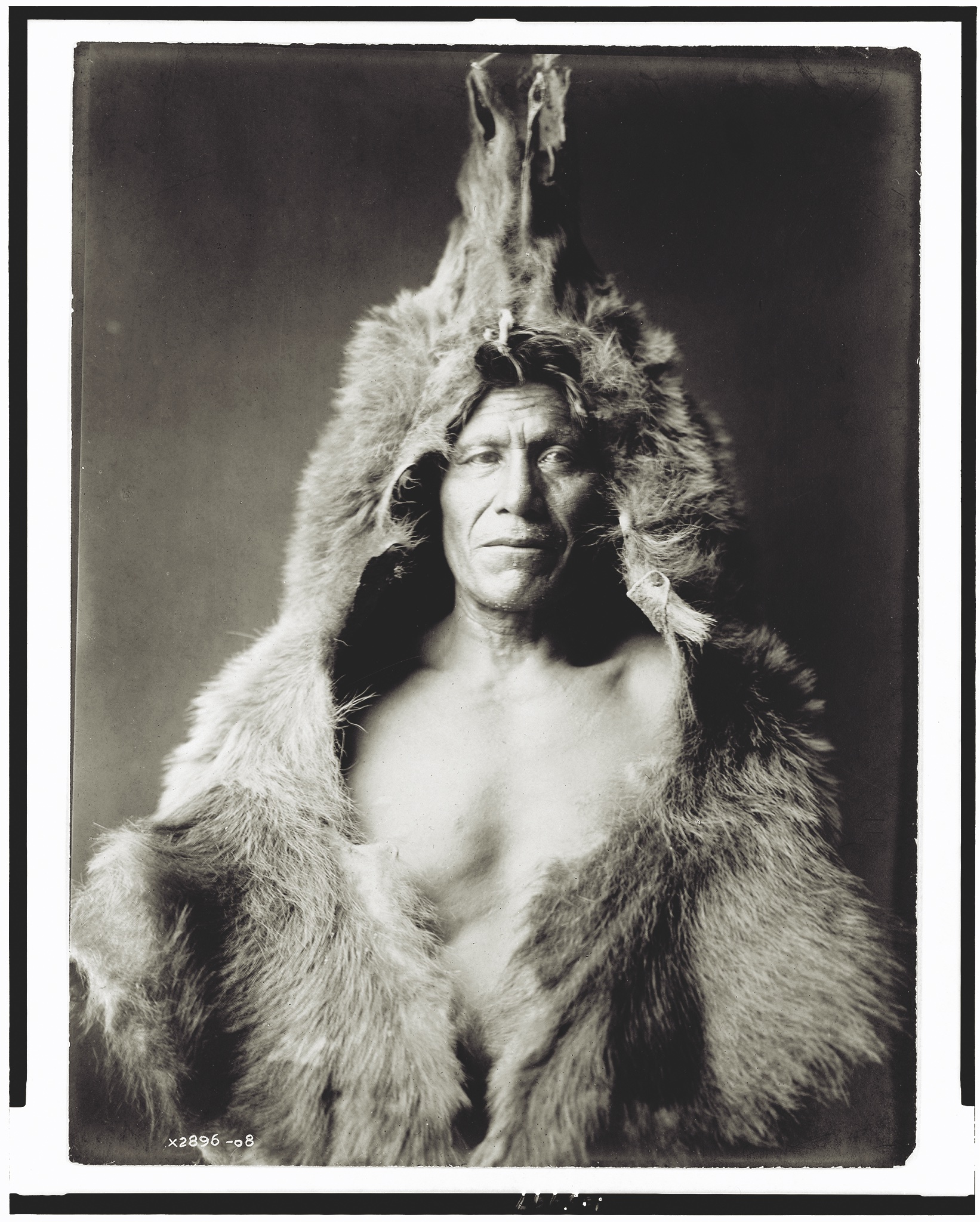

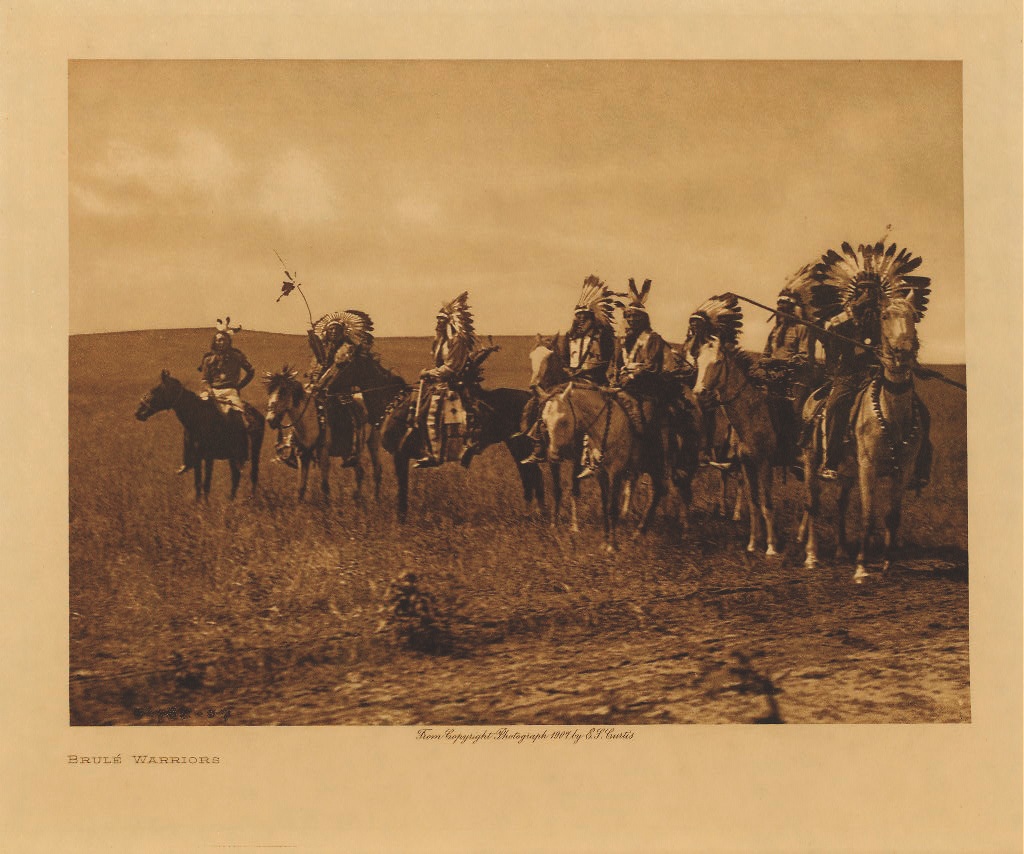

The site of the last great battles and tragic massacres in the Indian Wars, the Northern Plains were almost certainly the best known of all the places Curtis visited, and Curtis no doubt intended to photograph the storied chiefs and battlefields in Sioux and Crow (Apsaroke) country. What actually happened, however, when Curtis arrived and began photographing and speaking with survivors of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, including Native scouts who had been with Custer throughout the days of the campaign, is itself part of history. Through conversations with Sioux and Crow tribal members, Curtis saw the battle in a different light and forced recalcitrant historians to forgo mythology and rewrite the history of the fateful day. Custer had underestimated his opponents, left some of his command unsupported and failed to take heed of sound advice. Today we are rewriting the history of the American West, thanks in part, perhaps, to Edward Curtis.

Volume 4, Portfolio plate 117 (1908)

Goldtone Courtesy The Tim Peterson Family Collection

Volume 6, Portfolio plate 203 (1900)

Courtesy Library of Congress

Volume 4, Portfolio plate 112 (1908)

Volume 3, Portfolio plate 101 (1908)

Volume 5, Portfolio plate 149 (1908)

Volume 5, Portfolio plate 150 (1908)

Courtesy Library of Congress

Volume 4, Frontispiece (1908)

Courtesy Library of Congress

Volume 3, Facing page 36 (1907)

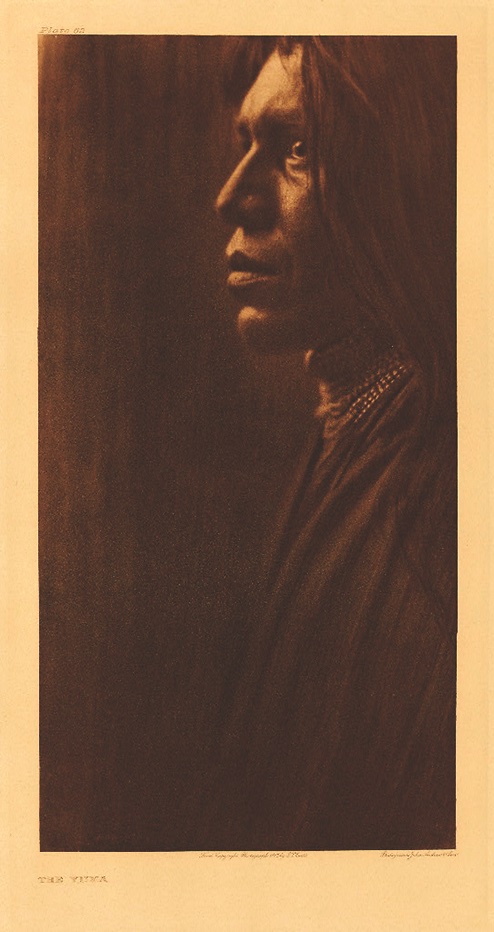

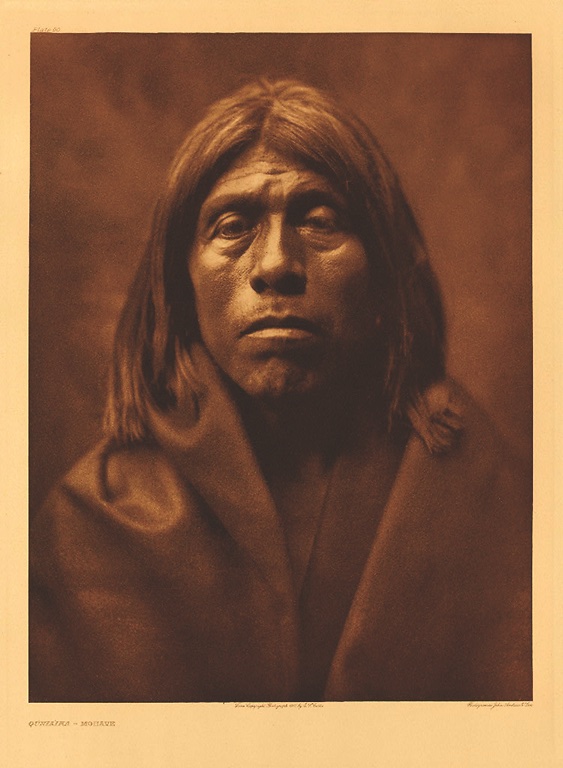

Shadow Catcher: People of the Desert and West Coast

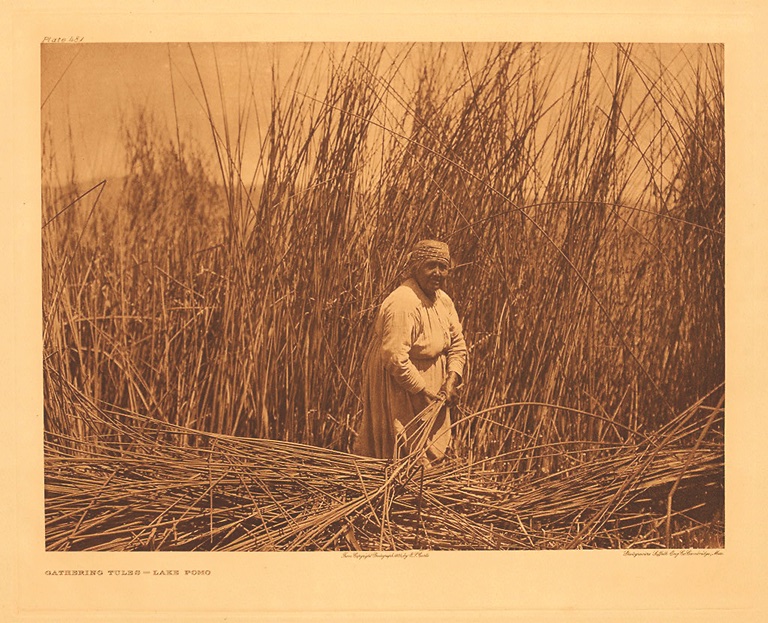

Curtis’s ambition and intention was to visit every tribe west of the Mississippi from the Arctic to Mexico. If you look at these two pages, taking in the Natives of the Arizona and California deserts and the California and Oregon coasts and mountains south of the Columbia River, you will have some idea of the sweep of Curtis’s travels and interests in this area alone. Mosa–Mohave and Yuma are artful compositions that, at first, seem to reinforce notions of Native Americans as stoic. Yet the piercing eyes of these models become windows into will and character. On the West Coast, Marcos–Palm Cañon Cahuilla is an inhabitant of the California desert, one of an ancient group who knew how to channel and manage water and thrive where others could not. Gathering Tules–Lake Pomo depicts the collecting of strong reeds or rushes used to fashion beautiful canoes.

Volume 2, Portfolio plate 46 (1907)

Volume 2, Portfolio plate 62 (1907)

Volume 7, Portfolio plate 244 (1910)

Courtesy Library of Congress

Volume 14, Portfolio plate 481 (1924)

Volume 13, Portfolio plate 467 (1923)

Volume 2, Portfolio plate 74 (1907)

Volume 7, Portfolio plate 221 (1910)

Courtesy Library of Congress

Volume 2, Portfolio plate 60 (1903)

Volume 13, Portfolio plate 470 (1923)

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

Dr. Tricia Loscher has curated Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West exhibitions, including the Cowboy Artists of America to posters and the Dr. Rennard Strickland Collection of Western Film History. Recently she co-curated an exhibit showcasing Maynard Dixon.

James D. Balestrieri is the principal of Balestrieri Fine Arts. He currently serves as communications manager for Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, estate and collections consultant for The Couse Foundation and Writer-in-Residence for the Clark Hulings Fund.