– All Photos by Candy Moulton Unless Otherwise Noted –

Alabama-born Levi Jordan left the border country between Louisiana and Arkansas in 1848 and resettled near the San Bernard River in Texas. He brought 12 enslaved men and women with him. Jordan and his family lived in a modest plantation home while the enslaved workers tilled the soil, raising sugar cane and cotton, the two principal crops of the region.

Jordan’s plantation expanded as he bought more workers until ultimately he had 144 enslaved individuals who tilled and harvested the fields, managed the sugarhouse production and took care of the grounds and the family home.

The Levi Jordan Plantation is now a Texas State Historic Site, located near Brazoria, open for special tours, on Saturdays. (A new visitors’ center is being planned.) Less than thirty minutes from the Jordan Plantation visit the Varner-Hogg Plantation near West Columbia, another Texas State Historic Site famous for its cotton and sugar production. Varner-Hogg’s Plantation has been restored with tours available that include the grounds, the location of the sugarhouse, the plantation home and a visitors’ center with a collection of artifacts and interpretation about the site. Some of the 20th-century buildings are now available for lodging.

Plantation Texas

In 1824, Virginian Martin Varner purchased a parcel of land from Stephen F. Austin, one of the 297 original grantees in Austin’s colony. Varner and his family obtained 4,428 acres and brought at least two enslaved men to farm and raise livestock on a small scale and establish a rum distillery. A decade later Varner sold the property to Columbus R. Patton of Kentucky. The Patton clan moved to Brazoria County bringing a large slave labor force. Soon the property became known as the Patton Place. It included a plantation house, smokehouse, sugar mill and slaves’ quarters, all built by the enslaved men using bricks they made by hand.

The sugar cane enterprise developed by Columbus Patton included a two-story mill, one of the largest in the region. Patton held on to the plantation until 1854 when, due to ill health, the property became mired in family wrangling, and, later, probate courts after his death. Eventually, in 1876, the Texas Land Company purchased the plantation and work shifted from sugar production to ranching, employing many African American cowboys.

Former Texas Gov. James Stephen Hogg bought the property in 1901, believing there was an oil reserve under the land. While he never struck large quantities of oil during his lifetime, after his death, production did occur, making his heirs quite wealthy. Ultimately, his daughter, Ima Hogg, donated the property to the State of Texas and it is now a State Historic Site reflecting her collection of decorative arts and her admiration for George Washington.

From these two plantations, we can now head west along a route that was used to ship cotton from plantations in this area of Texas to markets in Mexico and elsewhere.

Texas Gulf Coast Heritage

My route is from the Varner-Hogg Plantation in West Columbia, Texas, to the Levi Jordan Plantation near Brazoria, and then west to Cuero for a visit to the Chisholm Trail Heritage Museum. From there I traveled southwest on U.S. 183 and U.S. 77 to Corpus Christi and eventually to Kingsville and Sarita.

At Corpus Christi, I detoured to Padre Island National Seashore. I’m not certain what I expected to find here, but I certainly did not anticipate that the landscape would remind me of the Nebraska Sandhills. While there were areas of expansive beachfront—miles and miles of it on the longest stretch of undeveloped barrier island in the world—what struck me was the interior of the island with its gentle hills covered with waving grass.

– Photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

I could imagine cattle grazing this landscape, and from the early 1800s until 1970 it was used for ranching. Patrick Dunn owned most of the island by the 1940s, ranching there until the 1960s when he sold to the National Park Service, which subsequently established Padre Island National Seashore.

Coastal Ranching Empires

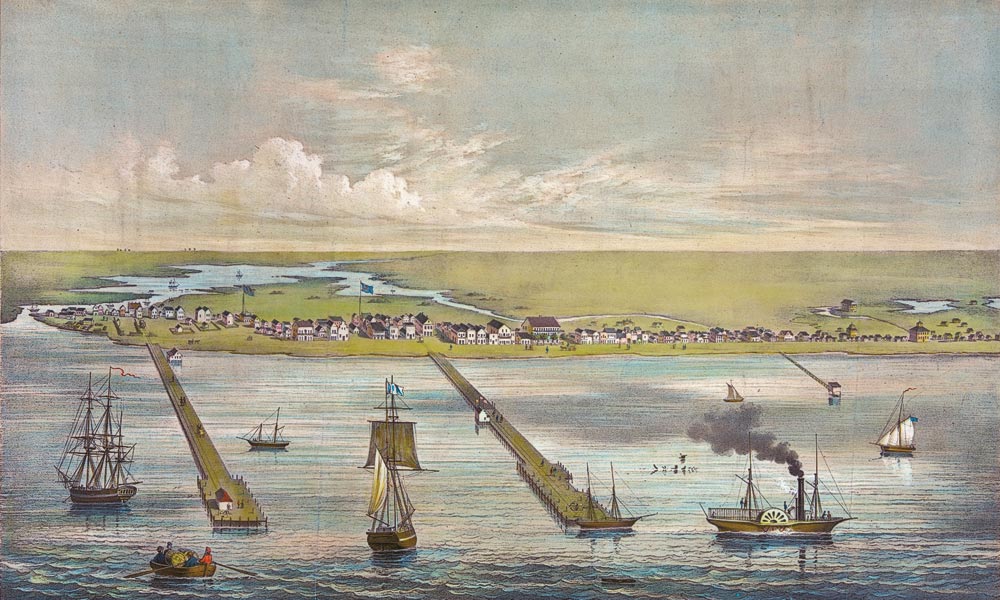

In the same way that the sugar and cotton plantations, owned by Levi Jordan and Martin Varner and later Governor Hogg, were cornerstone properties in southeastern Texas, the expansive properties owned by Mifflin Kenedy and Richard King dominated Southern Texas. Those two men were both steamboat captains before they became cattle kings.

Kenedy, born in 1818 to Quaker parents in Chester County, Pennsylvania, left home in the spring of 1834, sailing as a cabin boy on the Star of Philadelphia, bound for Calcutta, India. He would later become a clerk on a river steamer and ultimately would captain steamers on the Ohio, Missouri and Mississippi rivers. When acting as a substitute captain on the Champion, plying the Apalachicola and Chattahoochee rivers in Florida, he met Richard King.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Kenedy and King: Emperors of Texas

In 1850 Kenedy and King formed a steamship partnership with Brownsville founder Charles Stillman, called M. Kenedy and Company. They had already made the move to Texas and, during the Civil War, had made a fortune trading cotton, hauling it along a route known as “The Cotton Road” down to Brownsville, Texas, where they loaded it onto steamboats for transport to markets in Mexico, or to ships that could take it to other foreign markets, away from the blockade established by Union forces.

– Photos Courtesy Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress –

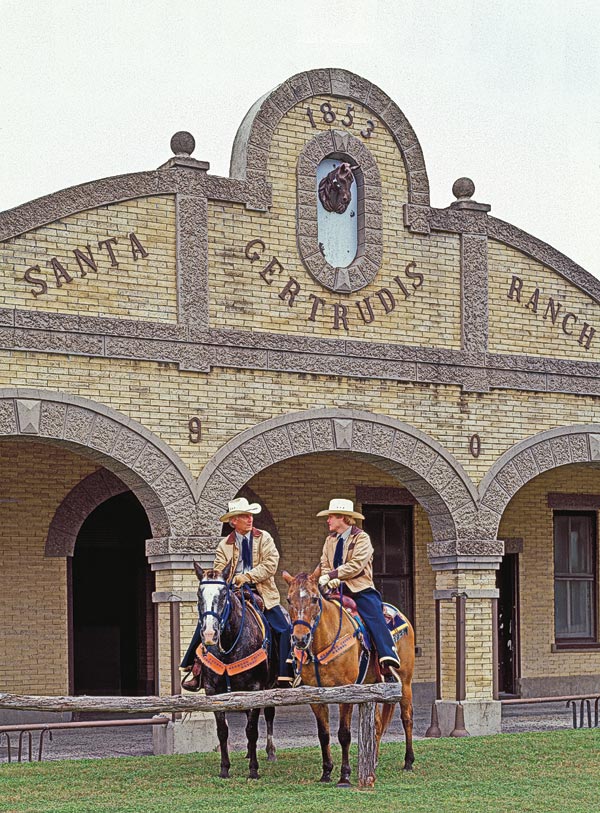

In 1860, Kenedy and King purchased the Santa Gertrudis Ranch, which they operated jointly for eight years until Kenedy sold out to King. Kenedy later purchased the Lurales Ranch near Corpus Christi.

King and his wife, Henrietta, would expand their operations in the area called the Wild Horse Desert, ultimately building it into one of Texas’s largest ranches, encompassing 825,000 acres and becoming internationally known for Santa Gertrudis cattle and quarter horses.

The ranch spawned a town—Kingsville—and Henrietta King and her son-in-law,

Robert J. Kleberg, were instrumental in bringing the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico railroad to the area.

Mifflin Kenedy, meantime, ranched on the Lurales and other property south and west of the King Ranch. His operation, too, created a town–Sarita, named for his daughter.

While the King family continues to own and operate the empire started by Robert and Henrietta King, the Kenedy family line died out, even though the Kenedy Ranch remains operational.

To learn more about the King Ranch, visit the King Ranch Museum in Kingsville, or better, take a tour of the ranch property. The history tour gives an overview of King’s story and an opportunity to see a small section of this expansive ranch, including the old Cotton Road, plus the ranch housing, horses and cattle. Other tours focus on birds and wildlife. I saw my first-ever alligator as we took the history tour!

In Sarita visit the Kenedy Ranch Museum which shares the story of Mifflin Kenedy. This small museum has a full wall mural and audio program depicting area history. While the Kenedy story is often overshadowed by the King Ranch narrative, it is every bit as interesting. It is perhaps likely that had the two steamboat captains not met in Florida, neither would have made the mark they did in Texas.

What the sugar- and cotton-producing slave plantations have in common with the ranching empires of Kenedy and King, are stories of people making a living from the land.

Candy Moulton is a regular contributor to True West. When not writing articles or managing the Western Writers of America, she is busy developing films and multimedia programs for museums and visitors’ centers in the West.