In a fast-moving world where MTV has replaced live concerts and music is often delivered digitally off a “jukebox” known as a PC, can there still be room for a real live, old-fashioned balladeer?

In a fast-moving world where MTV has replaced live concerts and music is often delivered digitally off a “jukebox” known as a PC, can there still be room for a real live, old-fashioned balladeer?

Absolutely—if you’re Don Edwards, a self-proclaimed minstrel of Western music. “That’s how I see myself,” he said in a recent interview for True West, “carrying on the tradition of bringing music to the people; one person, one song at a time.” Edwards, originally an eastern transplant to Texas, proves that the West is truly a state of mind, as well as a region. No one sings more faithfully the old songs of the cowboy or lives closer to the cowboy code than this authentic musician.

Raised in the era of the singing cowboys, Gene Autry and Tex Ritter to name a couple, Edwards knew by the age of nine that he wanted to sing. His father played the old 78s as he grew up, especially music by Mac McClintock, and Edwards was deeply influenced by the sound and subject of these early Western musicians. By the time the folk-music era blossomed in the ’60s, he was already bringing his warm and mellow style to audiences in the East, but they never really understood him. It wasn’t until a decade later when he took his act to the clubs of Fort Worth and finally to Elko, Nevada, to the stages of the Western Folklife Center’s annual Cowboy Poetry Gathering, that he truly found his niche.

In 1968, Edwards went to Nashville, at the time when the hugely popular country music of the ’50s was already on the wane. Audiences there actually told him he belonged in Greenwich Village! Producers didn’t understand his brand of Western music and tried to make it sound more like the popular radio music of the time, wanting more frills, more layers. He knew he had to move on.

The Western boom launched by the film Urban Cowboy in the ’80s came and went, turning Western music briefly into a pop-disco phenomenon and popularizing blue jeans for a new urban consumer. In music, the closest thing to real Western at the time was Kenny Rogers, a far cry from Edwards’ style.

One night, while playing at the White Elephant Saloon in Fort Worth, someone in the audience told him he ought to head for Elko, which he decided to do. From then on, his life has never been the same. Since his first appearances there, Edwards has tapped into the growing appreciation of authentic, historically based music of the West, and his career has flourished. “Performing at Elko has opened all kinds of doors. I’ve met so many great people: it’s still a very special time and place for me.”

Edwards eventually signed with the Western Jubilee Recording Company in Colorado Springs, Colorado, which liked what he had to offer and took him on, saying, “Just do what you like to do.” Credit also goes to Scott O’Malley and Michael Evans who soon became his distributors, largely responsible for making Edwards the familiar face and name in the Western music business he has become today.

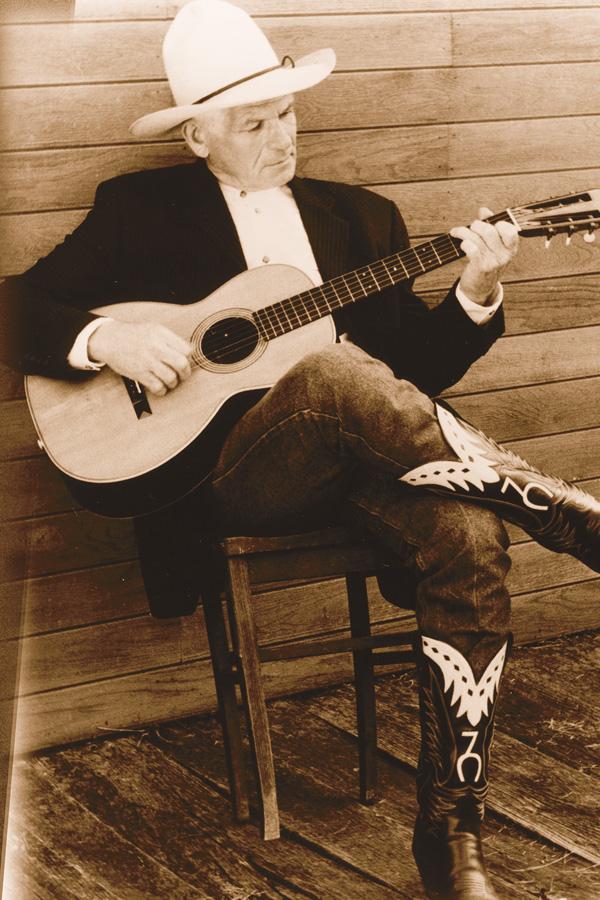

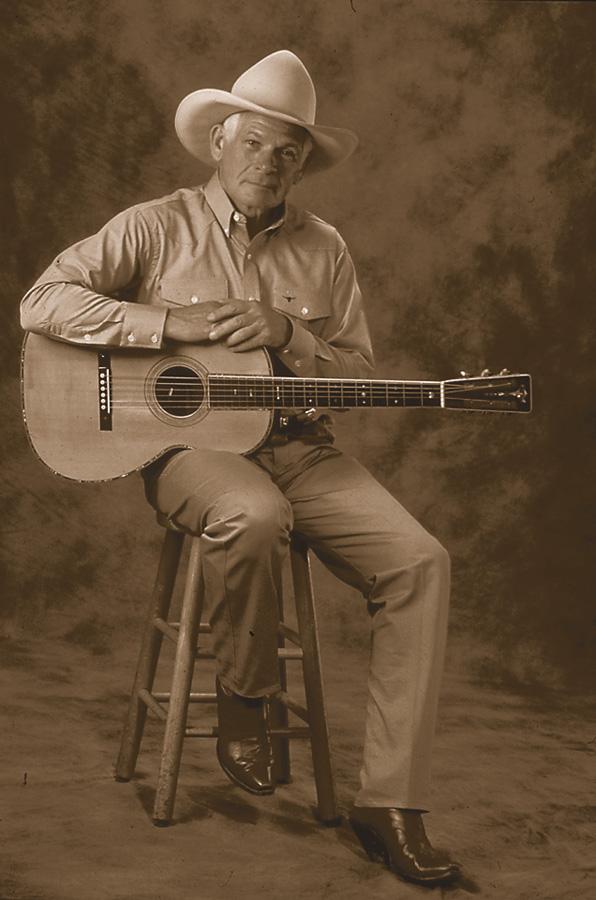

If Don Edwards’ musical sound is new to the reader, just think back to the “Golden Era” when cowboys were gentle heroes with strong hearts and had compassion for all things. When the simple strains of Western music both inspired and healed and even seduced the listener into believing there was a better world behind us, and just maybe (if we listened hard enough), ahead of us, too. Imagine the quintessential voice of the range drover, singing his cattle to sleep, or the love-struck cowboy longing for his girl. Edwards, a consummate stylist, has a pleasant voice that ranges from the deepest baritone to a full tenor, with a warm and expressive sound, feeling familiar and new at the same time. Maturity has only lent depth and credibility to a voice that almost sounds ageless. From the passionate songs of legendary Marty Robbins to the classic titles of the old Western tradition, Don Edwards handles them all. Also known for his expert yodeling ability (a crowd-pleaser everywhere), Edwards also plays the banjo and is a skilled musician, owning a prestigious collection of acoustic guitars.

“When I was playing for audiences in my early days,” he explains, “we sometimes played what was then called ‘country music.’ I had a string band and liked to perform swing, old cowboy songs, vaudeville tunes, and country blues.” Titles of his recorded music today only hint at his rich and extended repertoire. Highlights among 14 popular CDs are “West of Yesterday,” “Kin to the Wind—Memories of Marty Robbins,” “My Hero Gene Autry,” “Saddle Songs,” and “America’s Singing Cowboy.” Recognized by the Western Music Association, Edwards also has twice received the National Cowboy Hall of Fame’s Wrangler Award for Outstanding Traditional Music, for Chant of the Wanderer in 1992 and West of Yesterday in ’96.

“What I’m most interested in today,” Edwards says, “is the archival music: the old, historic pieces. I believe if we don’t preserve these early tunes, they’re going to be gone forever. Preserving them means bringing them to light.” Edwards points out that in his own early days, he and other singers were writing new songs in the tradition. “My work was rooted in the Western mentality. Now, I’m more interested in research, trying to put together the threads that built the tradition, taking a look at voices and stories that have been neglected—the work of singer Walt LaRue for example.”

By focusing on preservation, Edwards is in fact passing the torch, ensuring a future for a new generation to interpret. “You have to play the music to keep it alive; even if there’s just a fragment to work with, you can add to it. At the moment, I’m currently redoing my old songbook with tablature since people who bought it were guitar players and wanted more. Another project was initiated by a performance at Yale University where one of the college deans remarked that my music evoked a sense of the blues, at least to her ear. Further discussion clarified that when I sang, she heard the same delivery and structure of the early black musicians she loved. That clicked for me. I’d always thought there was a link. With the research I’ve done, now I’m sure of it.”

Edwards notes that, in the early days, music was one of the few professions where there was no prejudice; success was about how well you played, not who you were. So the opportunity for enrichment was huge. “Players got together all over the country and shared what they had. A great resource for early work is the anthology created by Jack Thorpe in 1908. Thorpe was the first man to collect and publish the songs of the old cowboys. Like him, I guess I’ve become a music ethnologist.”

Don Edwards’ future is one of his own design, geared toward reaching ever-wider audiences through personal appearances. As a result of a brief role singing in Robert Redford’s huge film success The Horse Whisperer, Edwards gained instant recognition with a nation of filmgoers. A cable TV spot promoting a double CD recorded by Don airs throughout the West and has brought unexpectedly high returns. Warm audience response in terms of packed houses and brisk sales is a testament not only to Edwards’ personal success, but also, to quote Bob Dylan, “to the changin’ of the times.”

“I believe there’s a clear return ahead,” Edwards says. “A way back to traditional values. When you think about it, we live in a culture that doesn’t value much. Audiences often listen to what I have to say with a sense of nostalgia, even in college towns. I feel like America’s kids are hungry for something that’s real. For personal contact, for the story. And for the frontier that existed long before cyber-space. Remember, the greatest folk hero that ever lived is the American cowboy. Everyone recognizes him.”

For every cowboy entertainer, there’s a conflict between life on the road and the life that defines the man. Living the cowboy life gives anchor, reference and meaning to Western music, although being a cowboy is not requisite to playing Western music. In Edwards’ case, he and his wife, Cathy, live on a 482-acre ranch in Texas that suits his lifestyle. His wife helps him manage his career and often tours with him as well. “She makes me feel grounded,” Edwards says, admiration in his voice. “She does all my homework.” In any case, when he’s home he feels that he is a part of the greater Western community and relates to the cattlemen who live on the land he loves.

“In a way, I represent everybody in the lifestyle and that works for me. I don’t try to go everywhere, penetrating the bluegrass market or Country. I know who I am and I’m comfortable with it. In mainstream, where music is manufactured for mass consumption, there are very few people who have succeeded in bringing the Western sound to audiences. Vince Gill, Marty Stuart, and Lee Roy Parnell are three notable exceptions. But America is listening: the recent soundtrack to the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, a mix of bluegrass country and western blues, sold nearly two million units in nine weeks. That’s good news for us all.”

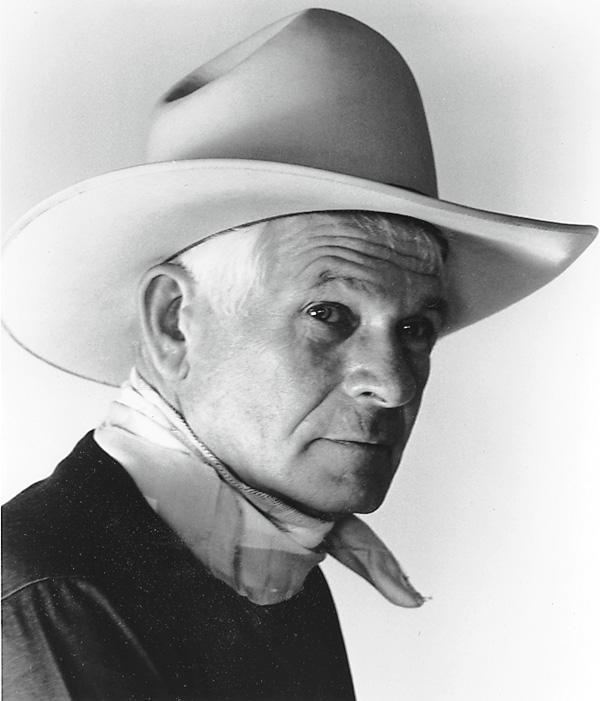

In a culture that worships youth, Don Edwards is no anomaly, but rather proof that talent has staying power and sex appeal. More popular today than at any time in his career, Edwards’ white hair and piercing blue eyes brand him as an attractive entertainer. Young and old alike think he’s “cool.”

“What luck,” he adds. “After all, in what other industry does one have the staying power I have except in the music industry?” Icons like Johnny Cash would agree. But the point is not that Edwards has grown children and grandchildren, but that his ability to reach the heart of his audience has not been diminished by his years, only enhanced by them. In addition to recognition, he now also has a hard-won, signature style, plus a measure of authority and credibility that can only come from the passing of time and the wisdom gained by it.

When asked if Edwards himself had reached his personal goals, he confirmed, “I believe I’ve accomplished what I set out to do. And, I’m still doing it. Currently I’m working on a record with Norman Blake and Peter Rowan called High Lonesome Cowboy, plus I continue to collect old 78s, songbooks, anything of historical value to further define what I sing.”

In some ways Don Edwards is actually a curator, not just an entertainer, himself a kind of living history museum. “I believe that we’re all a part of a net of music survival,” he adds. “We owe a debt to each other. When you think about the men who got early starts like Ian Tyson and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott—gosh, we’re all getting up there. But we’ve continued the legacy of the balladeer and that’s what’s important.”

Edwards points out that words like minstrel or balladeer are terms this culture barely understands. He reminds us that the early songsters were men who sang everything. They told the old stories and the new ones. “No matter what you do in life today,” Edwards adds, “you just don’t know who you are without the past. I owe a debt to those who went before. So, even if I’m looked at as an elder statesmen by some, I know I’m the lucky one. I’m a steward of this music no less than a rancher is a steward of the land.”

Corinne J. Brown is a Colorado-born Western music wannabe who survived the folk era only to be eternally challenged by flat picks and yodeling. Her first Western novel has just been published by Thorndike Five Star (a trilogy) and will happily

keep her writing instead of singing.

Photo Gallery

– Photo by Donald Kallaus –

– APhoto By Donald Kallaus –

– Photo by Donald Kallaus –