I haven’t seen fog this thick since … well, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen fog this thick, unless you count the time I walked into the room across the hall at my college dorm, and that fog wasn’t, ahem, natural. This is the kind of fog you expect to find on the coast, in London, in a horror movie or Casablanca, not traveling along U.S. Highway 385 in eastern Colorado where my handy-dandy Rand McNally tells me the only water to find is at places with names like Landsman … South Fork of the Republican … Arikaree.

I haven’t seen fog this thick since … well, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen fog this thick, unless you count the time I walked into the room across the hall at my college dorm, and that fog wasn’t, ahem, natural. This is the kind of fog you expect to find on the coast, in London, in a horror movie or Casablanca, not traveling along U.S. Highway 385 in eastern Colorado where my handy-dandy Rand McNally tells me the only water to find is at places with names like Landsman … South Fork of the Republican … Arikaree.

Despite the fog, I keep on chasing those Beecher’s Island boys.

You know the story. In August 1868, under Gen. Philip Sheridan’s orders, Maj. George Forsyth picked 50 civilian scouts, arming them with Spencer rifles, and set out after Cheyenne Indians. By September 5, the scouts had reached Fort Wallace in western Kansas. They hadn’t found any Indians.

No surprise there. Even today, Wallace, Kansas—home of a good museum thanks to the tireless effort of the Fort Wallace Memorial Association—doesn’t get much traffic along U.S. Highway 40 compared to I-70 just north. I’m seeing even less people—fog or no fog—here in Colorado.

Back to my story.

At dawn September 17, Forsyth’s scouts were attacked by a strong force of Cheyenne, perhaps as many as 600. Saddling their horses, the frontiersmen realized there was no escape, so Forsyth ordered his men to head to a sandbar in the middle of the Arikaree, back then known as “Dry Fork of the Republican River” or “Delaware Creek.” The battle of Beecher’s Island was on.

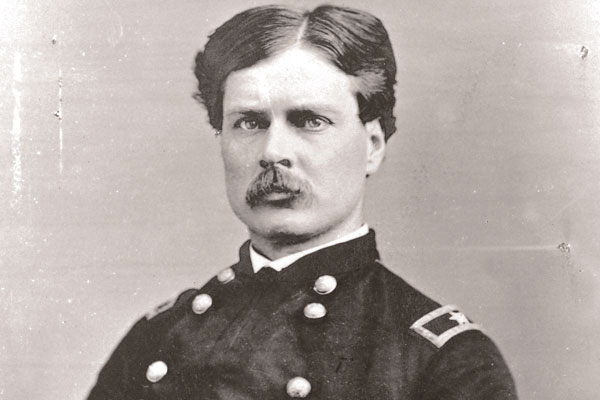

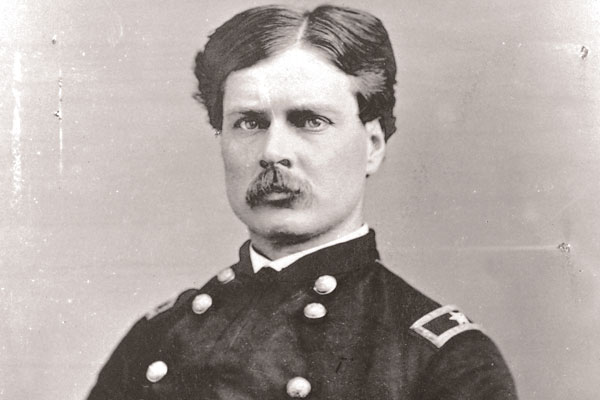

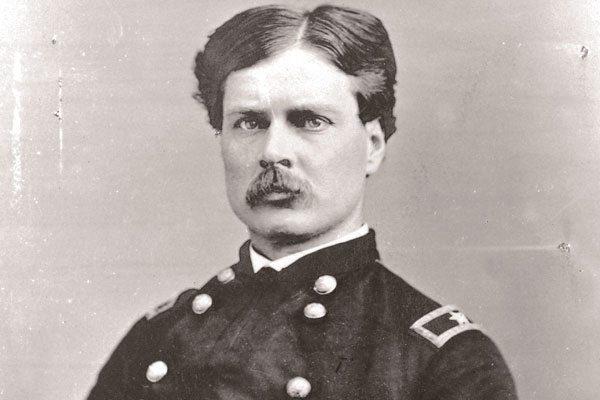

Cheyenne charges were repelled, but the boys took their licks. Forsyth’s exec, Lt. Frederick Beecher, was killed along with three others, including the acting surgeon. A fifth scout later died from wounds. Forsyth himself was wounded and sent a few of his men off to get help at Fort Wallace.

By most accounts, the battle was a two-day affair, ending, more or less, when Cheyenne leader Roman Nose was killed in a charge—the Cheyennes would remember the battle as the “Fight when Roman Nose was Killed”—but the ordeal at Beecher’s Island was just beginning. By September 20, Forsyth and his men were living on river water, mighty muddy, and horse meat, mighty spoiled. The men weren’t saved until September 25, when a command of 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers came from Fort Wallace. Most novels (Dee Brown’s under-rated 1967 gem, Action at Beecher Island, is one exception) tend to forget that part.

The story’s also well told up the road at the Wray Museum in Wray, Colorado, but I’m seeking the real place.

Not that that’s possible, and not because of the fog.

In 1905, Kansas and Colorado teamed up to establish a joint historical site and the Beecher’s Island Battlefield Monument. I find the turnoff and bounce across 10 miles of forgotten road, heading to the battlefield site. No surprise. I’m the only one here.

The original monument’s gone, and so is Beecher’s Island. Both were washed away in 1935 when the Arikaree flooded. Parts of the first monument were found, and became part of a new marker erected at the site. In 1976, the battlefield became a National Historic Site.

Beecher’s Island doesn’t get a whole lot of attention, and that’s too bad, because it really is a testament to courage. Courage of those scouts forced to eat spoiling horse meat. Courage of those Cheyennes, fighting to preserve their way of life.

Of course, I don’t think they had fog to deal with.