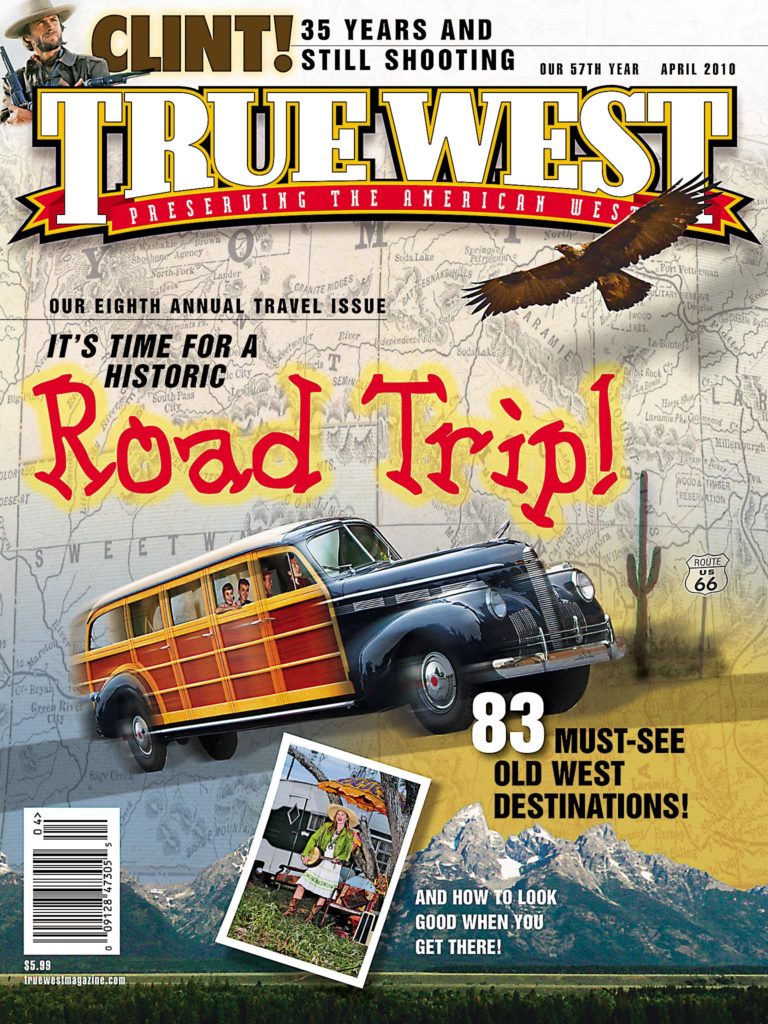

When one tries to describe Clint Eastwood, it’s difficult to avoid hyperbole, even when stating the simple facts of the man, as an actor and as a filmmaker.

His acting style is understated; over-the-top is not a place he is inclined to go. With a career that stretches back more than 50 years, less has always been more, and actions speak louder than words.

The same can be said of his style as a director. He is among the most self-effacing filmmakers in history, to the extent that some critics are convinced he lacks a recognizable style and that he generally errs on the side of caution.

But the fact is that Eastwood has gotten bolder as a filmmaker, in his direction and in his choice of material, and films such as Mystic River and Invictus are clear proof of his talents. When you consider that he may be peaking in his seventh decade, a little hyperbole is not out of order.

Eastwood was born on May 31, 1930, which means he will be turning 80 shortly. Since the year 2000, Eastwood has released nine movies, 10 if you count the one that’s due in December, Hereafter. He directed them all, starred in four and either contributed to, or composed outright, the scores to most of them.

To celebrate a career that shows no signs whatsoever of slowing down, Warner Brothers has decided to release a box set of his films beginning with Where Eagles Dare, from 1968, and finishing up with 2008’s Gran Torino. Eastwood has directed almost exclusively for Warners since 1976’s The Outlaw Josey Wales, but he has also acted in a considerable number of pictures under the Warners’ umbrella, including the entire Dirty Harry series, and all of these movies are included in the set.

In one single package, fans can now purchase 34 Clint Eastwood films on 19 discs, including 16 two-sided discs, as well as a short documentary by critic, historian and Eastwood confidant Richard Schickel. Warners has also promised to load the package with features and commentaries, which suggests that the extras that appeared on a handful of Eastwood’s pictures, such as in 1992’s Unforgiven and the 1970s-80s Dirty Harry series, will be carried over to the new set. Finally, Warners is including a 24-page sampler booklet with an extract from Schickel’s Clint: A Retrospective. That book, in its entirety, is available a la carte in March.

Warners is asking $179.98, while retailing the collection is going for around $130, which is a pretty good deal (that’s $6.84 per movie, not pricing all the extras). At the same time, Eastwood made great movies for other studios, such as 1968’s Coogan’s Bluff and Sergio Leone’s “Man With No Name” trilogy made in the 1960s, which are not a part of this package.

That’s important, particularly to readers of True West, because no matter what movies Eastwood has acted in or directed, for a great many Eastwood fans, he will always be thought of as a Western star of the first magnitude, which is as it should be. For the record, three of Eastwood’s best Westerns, 1976’s The Outlaw Josey Wales, 1985’s Pale Rider and the Oscar-winning Unforgiven, are in the collection. The rest of Eastwood’s movies, and three seasons of Rawhide, are all within reach, for anybody wishing to clear about six feet of bookshelf space.

To look at Eastwood’s career is to try to make sense of at least four decades of American cinema, and—if you put his Westerns into a more comprehensive overview of the history of the genre—his role as an icon, reaching back to the beginning, to the first Westerns made in the second decade of the 20th century. They ought to award degrees for that kind of study.

At a time when American movies were dumb and crass and cheaply made, and action heroes ruled the screens, Eastwood was paving a new path. When critics and armchair sociologists were howling about violence and Fascism in popular culture, Eastwood stood on the front lines with his .44 magnum and his steely catchphrases. When redneck movies were the rage and drive-in theaters still glittered at dusk, Eastwood fought bare-knuckled, in the company of a cuddly orangutan.

Through it all, Eastwood tweaked his material in ways only a handful of observers were canny enough to catch. Dirty Harry stepped completely out of his comfort zone in 1984’s Tightrope. The 1987 film Fatal Attraction can be seen as a rethinking of the first movie Eastwood directed, 1971’s Play Misty For Me. In 1971, he acted in Don Siegel’s The Beguiled, which went into a few dark places no Western had ever gone, but then so did Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter. That supernatural Western made in 1973 went after the townsfolk of 1952’s High Noon, literally, with a vengeance. Eastwood made Pale Rider as a ghostly reflection of 1953’s Shane, but with most of its sexual subtext laid bare and a gender switch that would have made famed Westerns director Howard Hawks proud.

The Outlaw Josey Wales is arguably Eastwood’s finest and certainly least cynical Western, which doesn’t explain why Unforgiven, which came 16 years later in 1992, is such a bitter piece. It’s great filmmaking, fantastic acting and wonderful writing, but very dark and cold at the core.

One film critic who has studied the sheer variety of these movies and the man who shaped them is Richard Schickel. He has been in the business for as long as Eastwood has been an actor; in fact, they were born three years apart. As wide ranging and comprehensive as Schickel’s work has been, he’ll probably be best remembered for his association with Eastwood; his highly regarded biography of Eastwood, published in 1996, is one of the higher points in his career. A portion of Schickel’s documentary, included in the box set, features the critic accompanying Eastwood as the actor/director walks about the Warner lot and reminisces.

Henry Cabot Beck: Tell me about being with Eastwood in the field.

Richard Schickel: I was on Unforgiven for several weeks; on A Perfect World, Bridges of Madison County for a day or two; several days in South Africa, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. I enjoy being on Clint’s sets because they’re very low key and pleasant to be at.

How would you describe him?

He’s, in essence, fairly shy; he’s not a guy who puts himself forward in a blustery, noisy, look-at-me sort of way; he’s a pretty cool cat.

At what point in Eastwood’s acting career do you think he first considered directing?

That experience of being on Rawhide, seven years doing that TV show. I think that was a profound learning experience for Clint. Hundreds of directors came through there, probably. He always said, “I learn from the good ones how to do it; I learn from the bad ones how not to do it.” I think that was a very good experience.

Do you agree that Eastwood is a more conservative director than either of his two biggest influences, Leone and Siegel?

Well, he’s not operatic, like Sergio [Leone], but he liked Sergio. I think he learned some things in that camp, especially the sort of panoramic camera shots and the emotional contrast that Sergio got into his films. But Don [Siegel] was the real mentor…. Clint is like Don in that Don was essentially a very straightforward screen storyteller.

Is that typical of someone who came to directing from editing?

Well, he made those Warners montages, and he was a very clean cut director, Don was. You don’t see a lot of directorial fancy work in his films.

There’s some stuff in Dirty Harry that’s a little bit of fancy work, but not a lot. I really think the main thing that Clint learned from Don was very careful preparation, leaving little to chance when he got out on location. I think the clean-cut style—tell a story as efficiently as you can—makes some pretty shots and stuff, nothing wrong with that, but talking with Clint over the years, that’s the impression I got, that he really liked Don’s way of making movies in the broadest of the term—not just the shots.

You could truthfully say that Clint’s work is very efficient, and it gets its point across, whatever the point is about the character or situation…. Clint was a serious student of acting, but he’s also a serious student of directing, with a deep knowledge of movie history and directorial history….

He’s not one of those directors who would say “that’s very Fellini-esque.” He’s just aware of what people have done. He knows what he likes and doesn’t like. And he’s smart about using ideas that he’s seen in other people’s movies.

In watching the Westerns that he made after the Spaghetti Westerns, such as High Plains Drifter, Pale Rider—

Oh, I love Pale Rider. I think that’s a great movie. It’s unique! The guy’s a ghost, appearing in reality, when, in fact, he’s dead. But it’s not laid in heavy; [Eastwood] leaves it a little bit ambiguous.

Also true of High Plains Drifter.

I like High Plains Drifter, but I really think Pale Rider is on the whole a better movie. Just an intriguing movie to me. You can’t really say why you like one movie instead of another—it’s maybe just how it hits you the first time you see it—but Pale Rider is a terrific movie.

I see people somewhat divided as to whether they prefer Unforgiven or The Outlaw Josey Wales as the best of all his Westerns. What’s your opinion?

Clint has said to me, “I think Outlaw is as good a movie as Unforgiven.” He said, “It just came [out] at the wrong time, when people weren’t wanting to take me seriously as an actor or director.” To my taste, it’s just as good a movie.

Which one of the two do you prefer?

I don’t know—it’s hard for me with Clint. We’ve become so close over the years that, as far as I’m concerned, I have no critical take on what my friend does. I like all of them, and I’m supportive of all of them.

Put to the test, though, I think I’d say that Unforgiven is a somewhat more intricate movie, not only stylistically, but morally. It’s a very interesting study in violence, and I think it goes a little deeper than the places Outlaw Josey Wales goes.

On the other hand, a lot of Clint’s movies are about families: how families are, in the case of Josey Wales, totally decimated, and how a new family gathers around him as he wanders through the wilderness. It’s interesting to me how many movies of his are about the creation of a family or the restitution of a family that is in trouble….

Clint’s own family—his mother and family and sister and all that—were very close. Although they had some economic trouble through the Depression, they were a really solid family. There’s nothing in his past that would say, “Oh, my family was decimated by something or another, and it was all booze and misery.” That’s not true; he comes from a very solid family. But the subject—what’s Million Dollar Baby but a “father-daughter love story,” as Clint puts it Surrogate father, surrogate daughter—it’s the creation of a little family.

Another movie that I think is very underrated, True Crime. That’s a family under terrible pressure, with the father about to be executed for a crime he didn’t commit. And Clint plays the figure who comes in and saves the father’s life, and saves a family that’s about to be destroyed.

I like that movie, but it’s a typical Clint movie about family. The Family. The family is under pressure—how do we relieve the pressure, how do we make things right with this family, or how do we constitute a family where one didn’t exist? That’s a big theme with Clint, and people don’t notice that. They notice the guns going off. You see that in Pale Rider. It’s a little family that’s struggling to stay in existence, and they’re under pressure from this vast mining interest that’s trying to destroy the little community and the little family. It’s the business of the stranger, Clint’s part, to hold them all together.

Do you feel Eastwood has stayed present, even as the iconic Western actor John Wayne fades from popular memory?

It is true that historical knowledge of movies in general is not what it once was, mainly, I think, because the movie-going community—the people who take movies really seriously—is a fairly small group now, and movies are not truly a mass media. They occasionally are, when something like [James Cameron’s 2009, 3-D movie] Avatar comes along, but basically people are not as passionately, collectively passionately, concerned about movies as they once were.

I think Wayne’s not entirely forgotten … but if you ask about Joel McCrea [laughs].

First of all, Eastwood is a director. Wayne only directed two movies, I think, and he needed help on both of them. [Wayne directed five movies, three uncredited: 1955’s Blood Alley, 1960’s The Alamo, 1961’s The Comancheros, 1968’s The Green Berets and 1971’s Big Jake.]

But I think there’s a sense of Clint, as an actor, having much more range than Duke Wayne, and as a director, desiring to make really serious movies on a wide range of subjects. I think people have a larger respect for Clint than they had for Wayne. We all love John Wayne, there’s no question of that, but I think a comparison in fact between Wayne and Eastwood, which is often made, is not really a very good comparison. There’s much more of a contrast.

To borrow a phrase from Clint in one of Clint’s movies, “a man’s gotta know his limitations.” John Wayne did know his limitations, not moving much beyond the Western, and later in his career, some cop pictures and so forth. He was very limited in the range of material he chose to take on. Clint has not abided by those limitations. It’s impossible to imagine Duke Wayne making Letters from Iwo Jima. Sands of Iwo Jima, okay! [Laughs.]

I mean the picture [Eastwood is] out doing now is a picture about people having near-death experiences. Do you think John Wayne would have taken on that subject? That’s nothing on John Wayne. He did what he did; he did what he did superbly.

Something that’s dissipated over the years, when Clint was starting out, people like [former New Yorker critic] Pauline Kael insisted that Clint was the new John Wayne, and that was ludicrous. There’s no comparison. Politically, aesthetically—Clint is much more interested in a much wider range of topics than John Wayne ever was.

My take on Clint is that he is much more curious as a person, about a lot of things. He reads very widely and looks at movies very widely. He often surprises me—“Have you seen such and such?”—some movie you wouldn’t expect Clint to be interested in, but it turns out he is!… There’s a wide-ranging intelligence and curiosity about Clint that’s not entirely comparable to, say, John Wayne.

Do you suppose Eastwood will act again?

I don’t have a definitive word on this; he’s never said, “I’ll never act again.” But I have the feeling that he is less interested now in acting, and certainly in acting in a movie that he’s also directing. I think demands on his energy, doing the double role, I think it’s too tiring for him. I was working with him when he was making Gran Torino; he was narrating my Warner Brothers history show. I remember he was doing the last hour of narration and fumbled a little bit more than he usually did. He said, “You have to excuse me. I’m just exhausted from doing this picture. It’s really hard work to do both things.” So I think he’s going to really very much concentrate just on directing.

What about the next picture, after the Matt Damon movie, Hereafter?

At this very moment, I am not aware that Clint has got something he’s interested in doing. I don’t think he’s got something he wants to start in the fall. That doesn’t mean he won’t find something. But I think he sort of feels—after two movies back to back, Invictus and the new one—“maybe I’ll sit around for six months, before I tackle something else.”