The rolling Appalachian foothills of northeast Tennessee, where George Maledon lies peacefully buried, is a long ways away from the 16-foot-long trapdoor at the gallows in Fort Smith, Arkansas. There, between 1875 and 1891, Maledon, a hangman for Judge Isaac C. Parker at the U.S. District Court of the Western District of Arkansas, reportedly sent a record number of men to their own eternal place. But has history gotten that wrong?

The rolling Appalachian foothills of northeast Tennessee, where George Maledon lies peacefully buried, is a long ways away from the 16-foot-long trapdoor at the gallows in Fort Smith, Arkansas. There, between 1875 and 1891, Maledon, a hangman for Judge Isaac C. Parker at the U.S. District Court of the Western District of Arkansas, reportedly sent a record number of men to their own eternal place. But has history gotten that wrong?

The Grim Reaper

A German immigrant born June 10, 1830, Maledon ventured west from Detroit, Michigan, as a young man, working at a lumber mill for the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. Shortly after his move, he secured a position on the police force in Fort Smith, Arkansas. During the Civil War, he served for the Union in the 1st Battery Arkansas Light Artillery. By the 1870s, he was back in Fort Smith, working for the Western District’s federal court, first as a guard, then as a deputy sheriff, then as court executioner. He also served periodically as a juror.

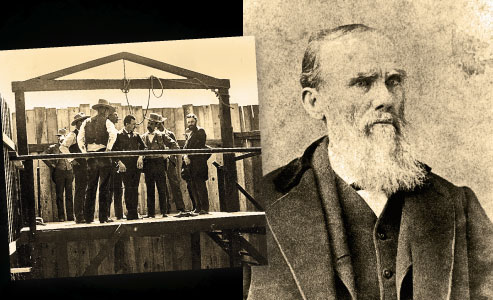

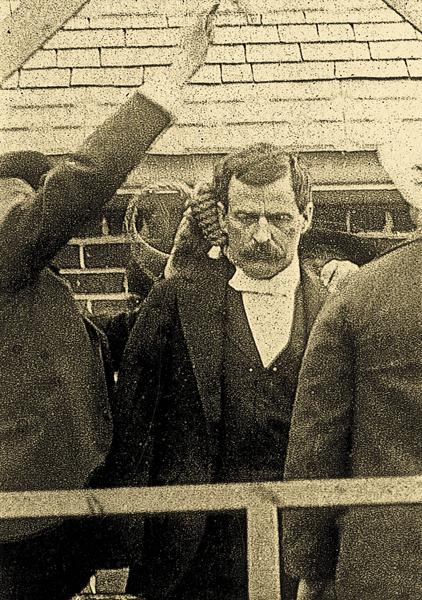

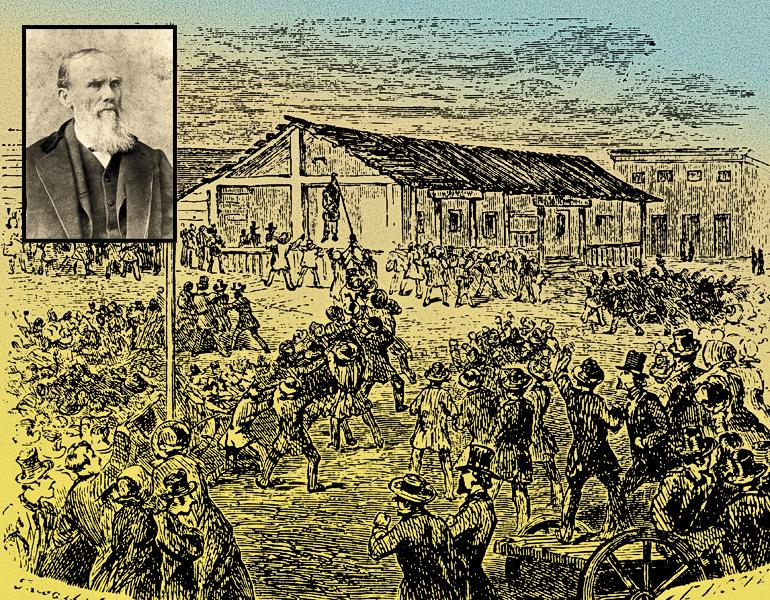

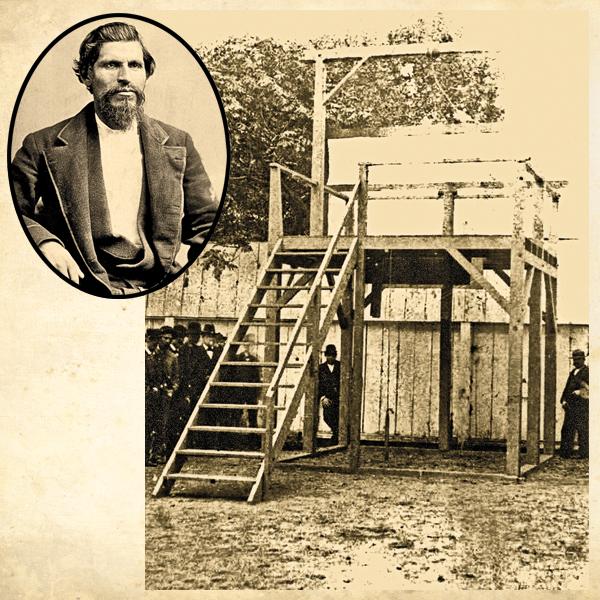

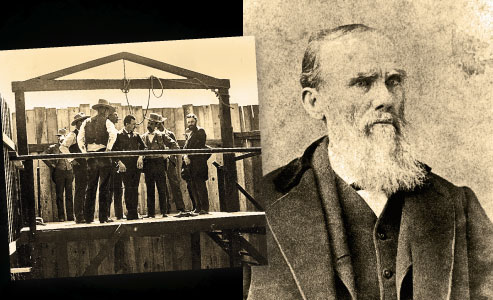

Small in stature, about five feet five inches (some reports state he was three inches taller) with a scruffy white beard, stooped shoulders, dark, piercing eyes and a fair complexion, Maledon faintly resembled portrayals of the Grim Reaper in the few photos that survived.

One newspaper reporter described Maledon as a “wispy little fellow.” Another, at the Fort Smith Elevator, described Maledon as so composed while performing his hanging duties that “launching a man into eternity appears to have no more effect on his nervous system than castor oil on a graven image.”

Newspaper accounts reported that Maledon led 60 (some reports claimed up to 81) men to the gallows, a greater number than anyone else in the nation. The numbers are where much of the Maledon story gets skewed. In 1887, for example, a January 21 article in the Fort Smith Elevator reported that he had assisted in the hangings “of about 50 men” up to that date.

Jerry Akins, author of Hangin’ Times in Fort Smith: A History of Executions in Judge Parker’s Court, says 50 hangings sounds like pure exaggeration. Both the Fort Smith National Historic Site and the future U.S. Marshals Museum now underway in Fort Smith consider Akins an expert on Judge Parker’s court.

“Maledon’s work was difficult to document,” Akins says. “He wasn’t even an employee of the courts or under the U.S. Marshals’ authority for at least 13 of the first hangings that took place. He also didn’t serve a continuous period of 22 years as Judge Parker’s hangman. In fact, he was a jail guard more often than he was an executioner.”

Career on Record

Some reports have Maledon serving as hangman as early as 1873, which cannot be proven conclusively, since the executioner went unnamed in official court accounts of the first 13 capital punishments.

We know that Maledon was a guard for the U.S. Marshals in 1871, when the court was moved to Fort Smith, but by that December, he was a disgruntled former employee.

In February 1872, Maledon was working as a deputy sheriff in Fort Smith when a local paper reported him shooting two prisoners who had attacked him while trying to escape the jail.

In September 1873, he went back to work as a guard. He participated in the October 10, 1873, execution of Tuni and Young Wolf, under executioner Charley Messler.

In March 1875, Maledon left the marshals and became deputy township constable. That same year, on May 10, Judge Parker held court for the first time in Fort Smith, taking over for his corrupt predecessor William Story.

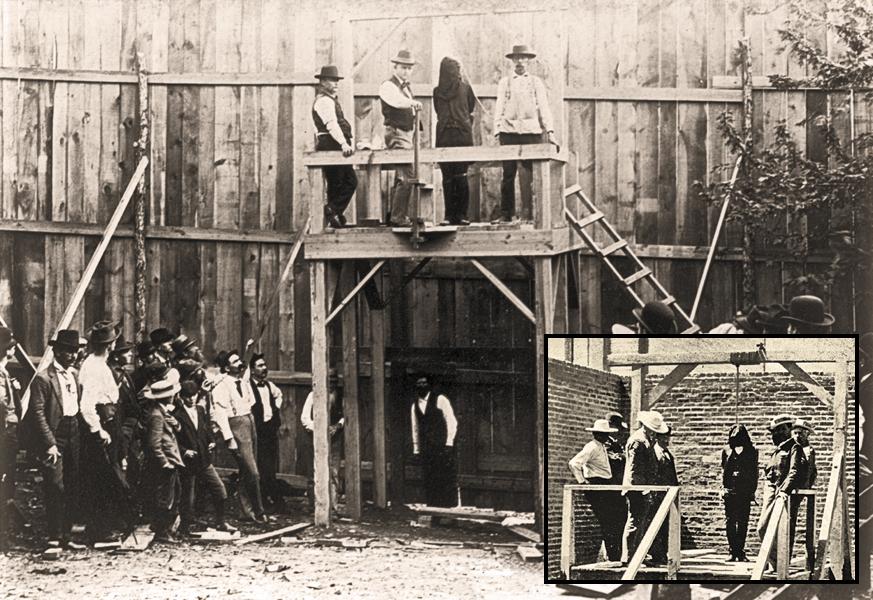

We do have a newspaper account reporting Parker’s first hangings, of six men at one time, that named Maledon as the executioner. Supposedly more than 5,000 people packed the jail yard to witness the executions on a “sturdy platform…six feet above the ground” with a “twelve-by-twelve inch overhead beam [supporting] the noose ropes” and a “slanted roof…in case of rain,” reported the Independent-Extra in Fort Smith on September 3, 1875. The paper noted, “…George Maledon, the hangman, adjusting the nooses about their necks.”

Akins says that account is discredited. Maledon was serving in the petit jury pool at the time of the execution. He wouldn’t go back to being on guard detail until October 14, 1878. The year 1878 is also when Fort Smith executions began being conducted privately, which may account for why specific instances of when Maledon served as hangman were not publicly reported.

“Another reason to doubt this 1875 article,” Akins says, “is that it has Parker speaking to the condemned before their execution. The only time Parker spoke to these men was from the bench, individually, at their sentencing.”

Maledon himself told The Chicago Tribune in 1887 that the first man he “ever had anything to do with” was John Childers, executed on August 15, 1873. But even he admitted he might not be recalling the date and year of his first execution accurately.

Later on, in the September 25, 1887, article, Maledon admitted he didn’t keep records of the executions: “I pay very little attention to criminal records of any kind….”

The truth, says Jessica Hougen, curator for the future U.S. Marshals Museum, is that much of Maledon’s story about his years in the Western District court is full of holes and inconsistencies.

“He was never a deputy marshal, as was widely reported. He also propagated his own myth after retiring as Judge Parker’s hangman,” she says. “Nobody really knows the truth from fiction when it comes to George Maledon. But at the same time, we do know when he was here in Fort Smith, he took his profession very seriously.”

Maledon made that clear to The Chicago Tribune in 1887: “I have got the business down fine, and know just how to prepare a noose and how to adjust one to make a complete and successful job. Of course I feel sorry for any man who is so unfortunate as to get himself hung [sic], but at the same time think a larger share of my sympathy is due the other fellow—the one that has been murdered.”

Taken to Task

Before Maledon retired in October 1891, due to deteriorating health, his life story got a boost after he met S.W. Harman, a publicity-seeking attorney who convinced the executioner to tour the Indian Territory and Southwest with a tent, showing off relics from the gallows, including handmade nooses and photos of several dead men Maledon had hanged.

From this venture came the 1898 book, Hell on the Border, which a few historical sticklers contend is “full of lies.” The book tour brought in the crowds, perpetuating Maledon’s version of his role as the “chief executioner” in Fort Smith.

The year before the book’s publication, an 1897 article took Maledon to task for his “wonderful tales.” “He did not hang the number of men he claims to have hanged,” reported the Fort Smith Weekly Elevator on September 24, 1897.

“He did not hang Cherokee Bill, and the number of men executed on the gallows here is nothing like so great as he represents,” the paper continued. “Besides, he was not the first executioner of the court here. The first six or eight men who stepped off the gallows here were hung [sic] by Charley Messler, a saloon keeper, well remembered by all of the old attaches of the court.”

The first man to step off the federal court’s gallows in Fort Smith was half-breed Cherokee John Childers, hanged by Messler’s noose on August 15, 1873. He had robbed and killed an Indian trader, Reyburn Wedding, in October 1870. He confessed to his crime while on the gallows.

The newspaper went after Maledon even further, by stating that, after Messler, Charles Burns “dropped a number.”

As far as Maledon went, the newspaper reported: “Maledon figured to some extent at several of the early executions, but only by tying the wrists and feet of the condemned and putting the black caps on their heads. If the records were looked up closely it would be discovered that only about half the men hanged in the old jail yard met death at his hand.”

How Many Did He Hang?

Akins has listened to the newspaper’s century-old request and examined the historical records, which are still unclear about how many hangings Maledon presided over. The records don’t even indicate which execution was his first.

Parker sentenced 160 people to death from 1875 to 1896, but of these, records show only 79 were executed, stated Michael J. Brodhead in a 2003 biography of Judge Parker. Many of Parker’s original cases were commuted. (Prior to Parker’s tenure, seven men were executed, for a grand

total of 86 men put to death between August 15, 1873, and July 30, 1896.)

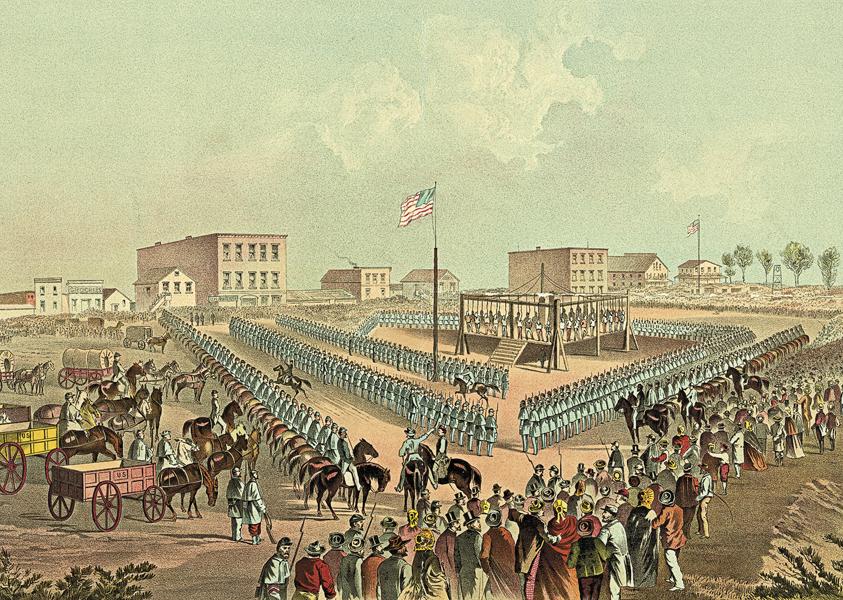

If the Fort Smith Weekly Elevator is correct that Maledon executed “only about half the men hanged,” Maledon executed roughly 39 men. That would mean his notorious hangman death count narrowly beats (or possibly doesn’t even beat) that of executioner William Duley for one singular event, hanging 38 Sioux in Mankato, Minnesota, in 1862—the nation’s largest mass execution.

The shroud of uncertainty continues to hang over this “Prince of Hangmen.” For a man who has put so many to death, we don’t know the specifics surrounding his death, most notably the date he died. The Fort Smith National Historic Site records his death date as June 5, 1911, while other sources state May 6, 1911. His birth and death dates are unlisted on his tombstone at the Mountain Home National Cemetery in Johnson City, Tennessee.

Perhaps that’s a fitting end to Maledon, who was eulogized as the man who hanged more men “than any known legal executioner of modern times” in America, a claim that this research puts to test.

The clouds of mystery around Maledon’s last years may also be why no one knows how and why he ended up in Johnson City, 781 miles from his Arkansas home and the legendary gallows in Fort Smith.

With more than a century’s worth of credence placed on the number of hangings credited to this “Prince of Hangmen,” Maledon’s moniker may remain stubbornly in place for years to come.

Marie Bartlett is a North Carolina-based freelance writer, a former member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and a current member of Western Writers of America. Visit OnceAWriter.com for details on her professional background.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Botched hanging photo courtesy Bill Secrest Collection; Decapitation photo True West Archives –

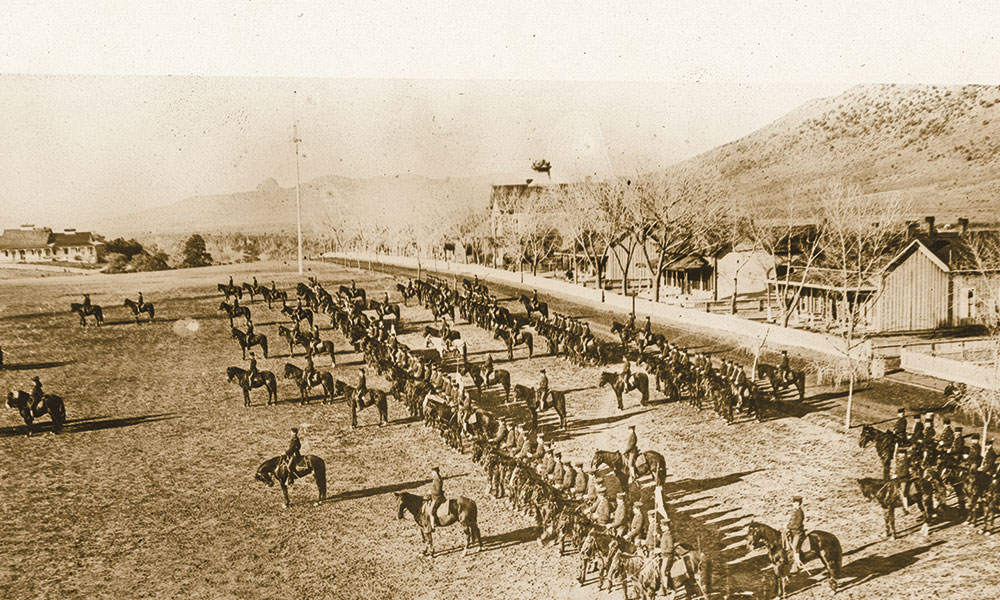

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Silan Lewis, a Choctaw convicted of murder, chose his executioner—childhood friend Lyman Pursely. In Wilburton, Indian Territory, on November 4, 1894, Lewis was blindfolded and kneeling on the ground, with two men holding his arms, when Sheriff Pursely fired his Winchester. The lawman missed the heart, though, and Lewis lived for three minutes as the sheriff smothered his old friend to death. This photo of the bungled execution created a controversy among U.S. senators and likely influenced the 1898 passage of the Curtis Act, which abolished tribal courts, like the one in Wilburton, and conferred full jurisdiction to federal courts. Lewis ended up the last man executed by Choctaw Nation.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Denver Public Library, Western History Department –

– Courtesy Fort Smith National Historic Site; Fort smith gallows illustration published in harper’s weekly, unknown issue –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Sharlot Hall Museum –

– Gallows photo courtesy Bandido by John Boessenecker, University of Oklahoma Press; Vasquez photo True West archives –