True Grit is an American masterpiece. The success of the film by Joel and Ethan Coen has surprised pundits and led, yet again, to predictions of the return of the Western.

No one has been more surprised by this than the Coen brothers, whose reputation as quirky, independent auteurs is threatened by the incredible commercial success of their new film. At $150 million and still going strong the film has already doubled the gross of their Academy award winner for best picture No Country for Old Men. With 10 Academy award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Cinematography, the film has emerged as both a critical and a commercial triumph.

The success of the film has led to a revival of interest in the Charles Portis novel that inspired both the classic 1969 film and the current Coen brothers production. “Charles Portis could be Cormac McCarthy if he wanted to, but he’d rather be funny,” declared Roy Blount Jr. The author is indeed a national treasure, a writer’s writer beloved by Blount, Larry McMurtry and Nora Ephron as a true American original. His novel has sold more than 100,000 copies since the film’s debut, securing spots on both the Amazon and The New York Times bestseller lists.

Born in El Dorado, Arkansas, in 1933 Portis served in the Marine Corps during the Korean War before returning to the University of Arkansas to study journalism. After graduation he worked for several Arkansas newspapers before joining the New York Herald Tribune alongside Tom Wolfe and Jimmy Breslin. He left the newspaper business in 1964 to pursue fiction, publishing his first novel, Norwood, in 1966. He followed it with True Grit in 1968, which was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post. The novel is the memoir of a strict Calvinist from the Ozarks who recalls her youthful grand adventure in the Indian Territory with an alcoholic, one-eyed lawman to avenge the murder of her father. The affection that grows between the girl and the old marshal is the heart of the tale, and it is not betrayed by a single false note of sentiment at any point in the book.

Portis’s agent sent galleys of True Grit to several film studios prior to publication. John Wayne, anxious to play Rooster Cogburn and planning to direct the film (as he had his previous film, The Green Berets), had his Batjac Productions place a $300,000 bid for the rights. Hal Wallis, the legendary Hollywood producer now headquartered at Paramount, outbid Batjac and other contenders to secure rights to the novel. He immediately offered Wayne the Cogburn role, along with a $1 million payday and 35 percent of the film. Wayne was delighted.

As the 1960s ended the film industry, along with the rest of American society, was going through dramatic, even traumatic, changes. This was highlighted by another film released in 1969 about a cowboy of sorts. Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman starred in Midnight Cowboy, which became the darling of the critics and the “New Hollywood,” winning the Best Picture Oscar for that year. But Wallis was “Old Hollywood” to the core. He had, after all, produced Captain Blood, The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, Now Voyager and dozens of other important films for Warner Brothers during the 1930s and 1940s. He was no stranger to Westerns either, with producer credits on Santa Fe Trail, They Died with Their Boots On, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Last Train from Gun Hill and The Sons of Katie Elder, where he had first worked with Wayne. Wallis brought in another representative of the “Old Hollywood,” that consummate professional Henry Hathaway, as director on the film. Hathaway had directed The Sons of Katie Elder, and he and Wayne were old friends dating back to when they first worked together in 1941 on The Shepherd of the Hills. The year before Hathaway had directed 5 Card Stud, with Robert Mitchum and Dean Martin, for Wallis. He had used screenwriter Marguerite Roberts for that film and now approached her to write True Grit.

Roberts was also “Old Hollywood,” but with a twist. In 1951 she had been blacklisted for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Along with her husband, screenwriter and novelist John Sanford, she had joined the Communist Party in 1939 but left it in 1947. Before then she had ranked as one of Hollywood’s top screenwriters throughout the 1930s and 1940s with both Paramount and MGM. The screenwriter for the Clark Gable classic Honky Tonk in 1941, as well as The Last Outpost, Ziegfield Girl and The Sea of Grass, Roberts could not work for a decade. Columbia Pictures finally offered her a contract in 1961 to write Diamond Head, and in 1968 Wallis hired her for 5 Card Stud. She had a natural affinity for Westerns populated with rugged men from her childhood in Greeley, Colorado. “I was weaned on stories about gunfighters and their doings, and I knew all the lingo too,” she recalled. “My grandfather came West as far as Colorado by covered wagon. He was a sheriff in the state’s wildest days.” She stuck closely to Portis’s novel in both structure and dialogue, diverging only in?Texas Ranger La Boeuf’s fate and in the final scene. She did not use Mattie as the narrator because her scenario shifted the focus to highlight Wayne’s Rooster Cogburn, making Mattie a supporting character. This is her most dramatic change from the novel and the great difference between her script and that of the Coen brothers. Wayne, famous for his conservative political views, was unconcerned with Roberts’ past politics but was deeply impressed by her writing skills. He repeatedly declared her screenplay for True Grit to be the finest he had ever read.

Wallis called on another veteran for cinematographer, and it proved an equally wise choice. Lucien Ballard had made his way to Hollywood in 1929 after getting kicked out of the University of Oklahoma. He found work as a laborer at Paramount and within a few months was assisting director Josef von Sternberg with his cameras, the beginning of a cinematography career with at least 130 credits. He came to the Western late, working with his friend Budd Boetticher, but proved to have an amazing eye for landscape and color. He had worked with Hathaway several times, but his greatest collaboration was with Sam Peckinpah with whom he would shoot five features. Ironically Ballard also shot Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch the same year he worked on True Grit. In the history of the Western film True Grit represents the last of the traditional Westerns, while The Wild Bunch is the first of the new, or post-modern, Westerns. They are both great films—although Peckinpah’s is superior—and they both benefitted enormously from the keen eye of Lucien Ballard. Vincent Canby, film critic for The New York Times, noted perceptively in his review of True Grit that: “Anyone interested in what good cinematography means can compare Ballard’s totally different contributions to The Wild Bunch and True Grit. In The Wild Bunch, the camera work is hard and bleak and largely unsentimental. The images of True Grit are as romantic and autumnal as its landscapes, which, in the course of the story, turn with the season from the colors of autumn to the white of winter.” And so it was with the Western film genre, with Ballard serving as undertaker for the grand finale of the traditional Western and as able midwife for the birth of the new Western.

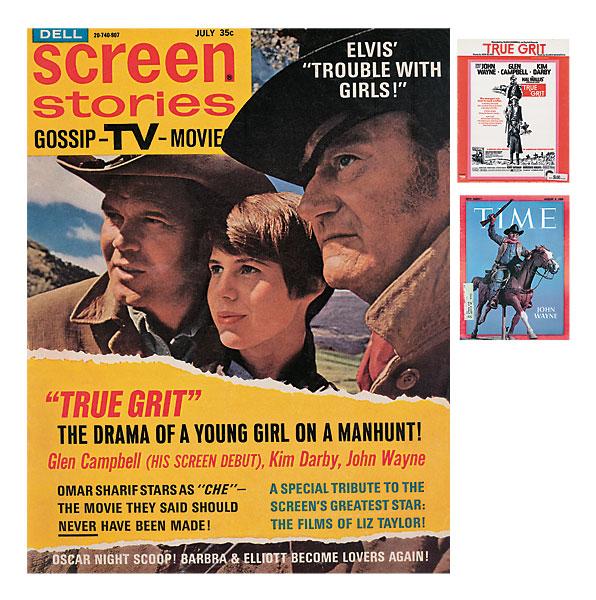

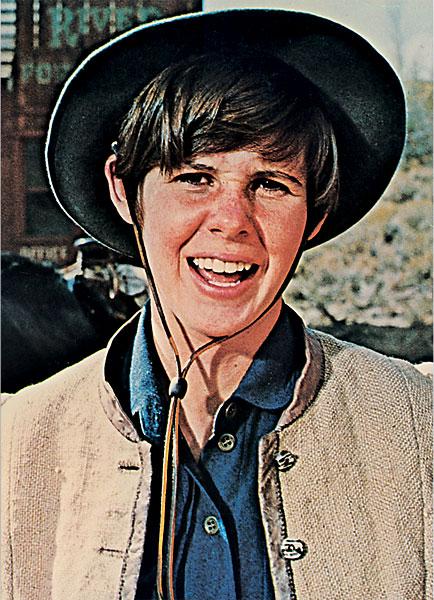

Wallis did not totally ignore the “New Hollywood.” He cast popular singer Glen Campbell as the Texas Ranger, Robert Duvall as Ned Pepper, Ron Soble as Boots Finch and Dennis Hopper as Moon, but it was for the role of Mattie Ross that he most wanted a star who could appeal to the youth market. His first choice was Mia Farrow, and she promptly agreed. While the script was being completed she went off to London to film Secret Ceremony with Robert Mitchum. He warned her that Hathaway could be a tyrant on the set, so she demanded that Wallis replace him with her Rosemary’s Baby director Roman Polanski. The deal promptly collapsed, and Wallis was without a leading lady with filming to begin in a few weeks. Watching television one evening Wallis found his lead, a complete unknown named Kim Darby. He quickly signed her for the film, although he grumbled over the high price she demanded to appear in the prestige production. A bit old for the role, she nevertheless acquitted herself well despite butting heads with the rigid Hathaway. Her characterization of Mattie (and her hairstyle) fit nicely as a proto-feminist in 1969.

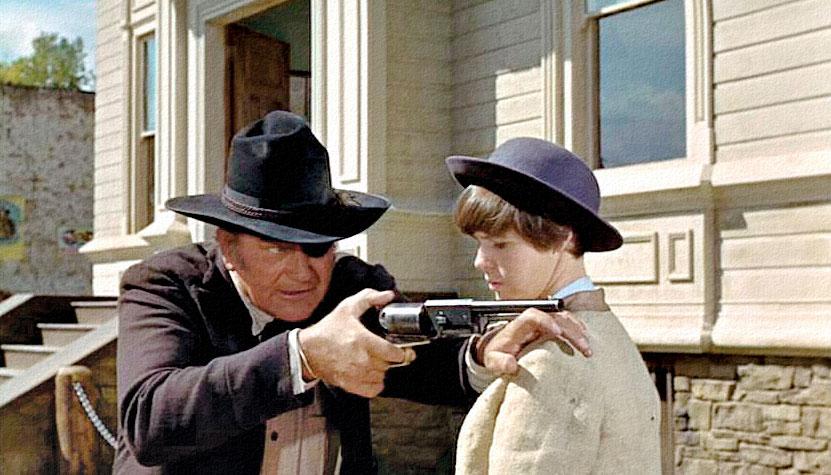

Filmed in southwestern Colorado, around the towns of Montrose and Ridgway, and at Mammoth Lakes, California, the movie exploited the majestic landscapes to full effect. Elmer Bernstein’s robust score further enhanced the majesty of the mountain vistas beautifully captured by Ballard’s camera. The climactic gunfight is one of the most enduring images in the history of the cinema. Wayne, however, was uncomfortable with even the modest level of violence in the film, especially in the cabin scene where Moon’s fingers are cut off (which is in the novel). “I thought it was going too far,” he declared. “Henry fell in love with this idea. I think he didn’t feel that the lines that I had growling at this fellow to try and get him to confess would mean anything unless there was a shocker ahead of it. So he certainly put a shocker ahead of it!” Amazingly, this was also the first time Wayne had ever uttered a profanity in a film: “Fill your hand, you son-of-a-bitch!”

“Self-parody is the price of style,” noted Stefan Kanfer in a 1969 Time cover story on Wayne. “John Wayne charges into it in his latest movie, True Grit. Like all consummate stylists, he remains unharmed. Only the enemy is hurt.” In that grand gallop across the mountain meadow Wayne might just as well have been charging into all the hippies, flagburners, ivory-tower intellectuals and counter-culture critics that so bedeviled his world—for it was indeed the grandest ride of a storied career and a fitting finale for an American icon.

Wayne’s Rooster Cogburn channels Wallace Beery and Victor McLaglen with abandon but consistently plays off his own public and screen persona to great effect. His roughhewn lawman’s coldness slowly melts before the young girl’s boldness (“she reminds me of me,” he says in a Roberts line not in the book). By the film’s end, when he looks at her fragile form in a sickbed, we see his deep affection and his fear of losing her etched in his craggy face.

In the film’s final scene (an invention that departs from the novel) Mattie proposes to Wayne that he reside next to her for eternity in the Ross family plot. In the original Roberts’ script Cogburn comments on Mattie’s budding love for the dead Texas Ranger when Mattie declares that she will never marry. Roberts foreshadowed this throughout her script. In the final version all such talk of the Texan is gone, replaced with an exhilarating finale celebrating the power of Wayne’s persona. In the novel the love Mattie feels for Rooster, in as much as she can feel true emotion for anyone, is subdued but made apparent in the book’s final pages. In the film it is but a subtext, as in some ancient tale from the age of chivalry—of love unspoken, unrequited, perfect in its purity.

Snow fell just before Hathaway shot the final scene. “We hadn’t counted on snow in that scene,” Wallis noted, “but when it fell we used it, working straight through until we finished the sequence.” Thus did nature conspire to provide a visual metaphor for Rooster’s (and Wayne’s) denouement. But even this can not daunt the hero, who jumps his horse over a fence calling back to the girl to “Come see a fat old man sometime.” The film thus ends on an upbeat note of exhilaration for the audience, for even death can not conquer their hero.

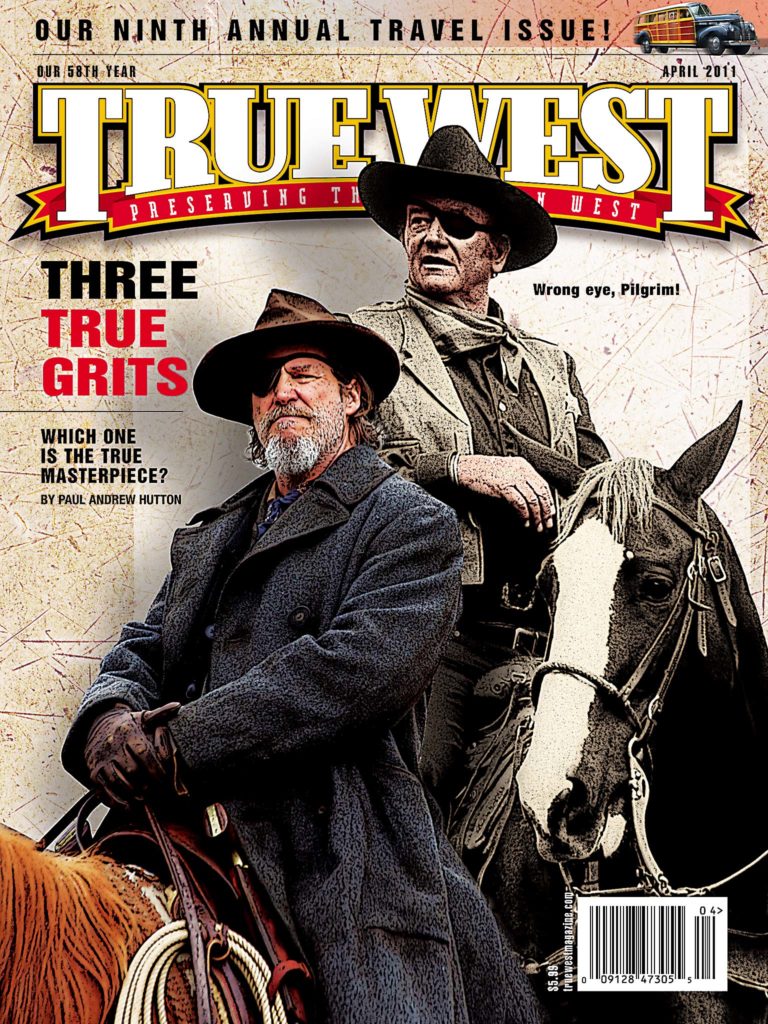

John Wayne casts quite a long shadow, still beloved as an American icon, so remaking his most famous film was not for anyone without true grit. Joel and Ethan Coen dodge the remake issue altogether by holding up the novel as their inspiration. “Our movie is from the Charles Portis novel,” Joel Coen asserted. “We haven’t seen the movie since it came out.” Jeff Bridges echoed that sentiment in a Hollywood Reporter interview: “The book is wonderful, and it reads like a Coen brothers script. I didn’t refer to John Wayne or that other movie at all. I took it totally fresh, like I would any other part.” Bridges probably did ignore Wayne’s broad portrayal, for his Cogburn owes much to his Bad Blake character in 2009’s Crazy Heart. Hailee Steinfeld, wise beyond her years, happily admitted to True West that she watched the Wayne film before auditioning: “Wayne was such an icon, not only as that character, but as himself. I just think he’s so cool.”

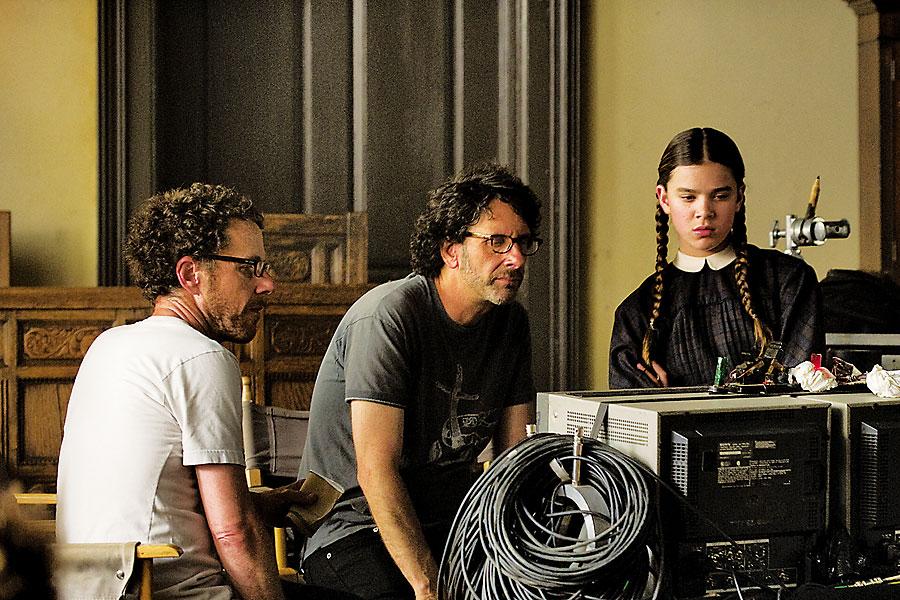

The casting of the 13-year-old Steinfeld was an inspiration, but the Coen brothers were as bedeviled in search of the right actress as Wallis had been back in 1968. They auditioned some 15,000 girls via online videos and open casting calls before finding newcomer Steinfeld 90 days before filming was to start. “Hailee could handle the language, which is where most of these kids fell short,” Joel Coen said. “She came into the room with Jeff, and she wasn’t at all taxed. She just went for it.” Indeed she did. Steinfeld is an absolute wonder in the film, more than holding her own with superb actors such as Bridges, Matt Damon and Dakin Matthews (as Stonehill). Since the Coen brothers’ script returned the focus to Mattie (with her narration as bookends to the action) the triumphant characterization of the young actress is absolutely critical to the success of the film.

Roger Ebert, still America’s wisest film critic, praised the Coen brothers for their past eccentric artistry but felt True Grit was reflective of a new direction for the quirky directors: “This is the first straight genre exercise in their career. It’s a loving one. Their craftsmanship is a wonder. Their casting is always inspired and exact. The cinematography by Roger Deakins reminds us of the glory that was, and can still be, the Western.”

Many critics have noted that the new film is truer to the novel than the Hathaway film. This is not true. Both films diverge from the book, as do all screen adaptations, at several key points. But both films are also remarkably faithful. The dialogue is strikingly similar in each film (because it is impossible to improve on Portis). The Coen brothers return to the novel for their final scene, but since it lacks the backstory material from the novel on Rooster and Cole Younger it is not as powerful as they might have wished. It is, however, depressingly somber in tone, which is the main thematic difference between the two films.

The current film also takes a harsher view of race relations than either the Hathaway film or the novel. In the hanging scene the two white prisoners are allowed to speak, but as the Indian begins to speak he is silenced. In the novel the Indian accepts Jesus as his savior and declares, “Now I must die like a man.” Mattie is impressed. In the Hathaway film the Indian is played by Jay Silverheels (famous for numerous film roles and as Tonto in the Lone Ranger television series); the original script gives the same speech as in the novel, but all the speeches were cut in the final film. In the novel and the Hathaway film Mattie treats her black employee and friend Yarnell Poindexter with great respect, but in the new film she is curt and brusque with him. The stable boy is black in the Coen brothers film, which is not the case in the novel. Also interesting is the kicking of the two young Indian children by Rooster in the new film. This is not in the Hathaway film at all, but in the novel they are teenage boys who are tormenting a mule, and one is white and the other is Indian. The point in the novel is that Rooster will not see animals tortured; it has nothing to do with race. Captain Boots Finch, the Choctaw Indian policeman, is an important character in the novel and in the Hathaway film (played by Ron Soble) but is absent from the new film. He is not only a friend to Cogburn but also clearly his equal as well. Race relations on the American frontier were far more complicated than the image presented by the Coen brothers.

The new film does not kill off the Texas Ranger but does allow him to vanish for a while (word is that Damon’s schedule forced this change in the story). Damon also nearly bites his tongue in two in another diversion from the novel that is the Coen brothers at their quirky best. Equally unique to the Coens are the decisions to leave the bodies unburied at the dugout (in the novel they are taken back in hopes of a reward) and to introduce a series of characters along the journey (the hanged man, the stoic Indian and the bear man). Perhaps these charmers were left over from O Brother, Where Art Thou.

The new film is fascinating and highly entertaining. It captures both the essence of the novel and the majesty of the West. Filmed in Granger, Texas (the town scenes), and in northern New Mexico its depiction of the majestic landscape is seductive and at times surreal. The desperate race to save Mattie is brilliantly filmed against a star-lit landscape reminiscent of Van Gogh, Thom Ross or at least any clear New Mexico evening. The West won these jaded, sophisticated filmmakers, and the result is a towering achievement for all involved.

“Time just gets away from us,” are Mattie Ross’s final words in the Coen brothers film.

Indeed it does. Has it really been 43 years since Portis’s True Grit was first published? Is it possible that 42 years have passed since John Wayne rode to glory and an Academy award in that same year that men first walked on the moon? And now the Coen brothers have captured lightning in a bottle yet again with a fresh version of this American classic for a new audience in a new century. Hopefully those who have so enjoyed both films will now take the time to read the book. It is no disservice to Marguerite Roberts and Henry Hathaway or to Joel and Ethan Coen to frankly say that all the wonderful rhythms of True Grit come not from Hollywood but from the talented pen of that overlooked American master Charles Portis. It is to him that we must give thanks for Mattie Ross’s “true account of how I avenged Frank Ross’s blood over in the Choctaw Nation when snow was on the ground.”

Photo Gallery

On the eve of the new True Grit release, more than 500 True Grit fanatics converged in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where the story is set, gathered at the actual Judge Parker’s gallows to turn each man, woman and child into Rooster Cogburn, the deputy U.S. marshal made famous first by John Wayne and now by Jeff Bridges. A crowd donned in eye patches, marshals’ badges and dozens of homemade costumes shouted out Rooster’s famous lines from his climactic showdown with Lucky Ned Pepper.

– Courtesy Fort Smith Convention & Visitors Bureau –

Thirteen-year-old Hailee Steinfeld (above) played 14-year-old Mattie Ross in the Coen brothers’ version.

– All True Grit images courtesy Paramount Pictures.–

Director of the 1969 film, Henry Hathaway (above right), in his trademark fedora, in 1970.