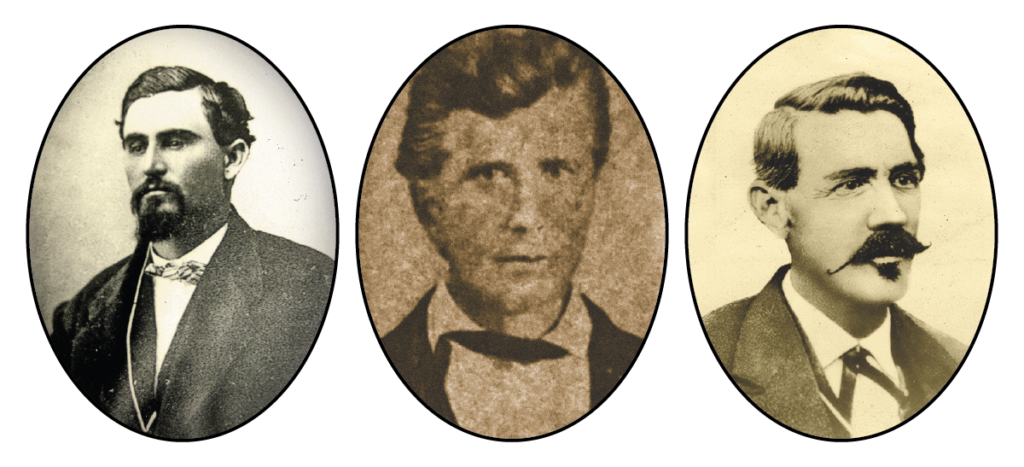

Oliver Loving and Charles Goodnight made history in 1866, and 120 years later Larry McMurtry made them legends.

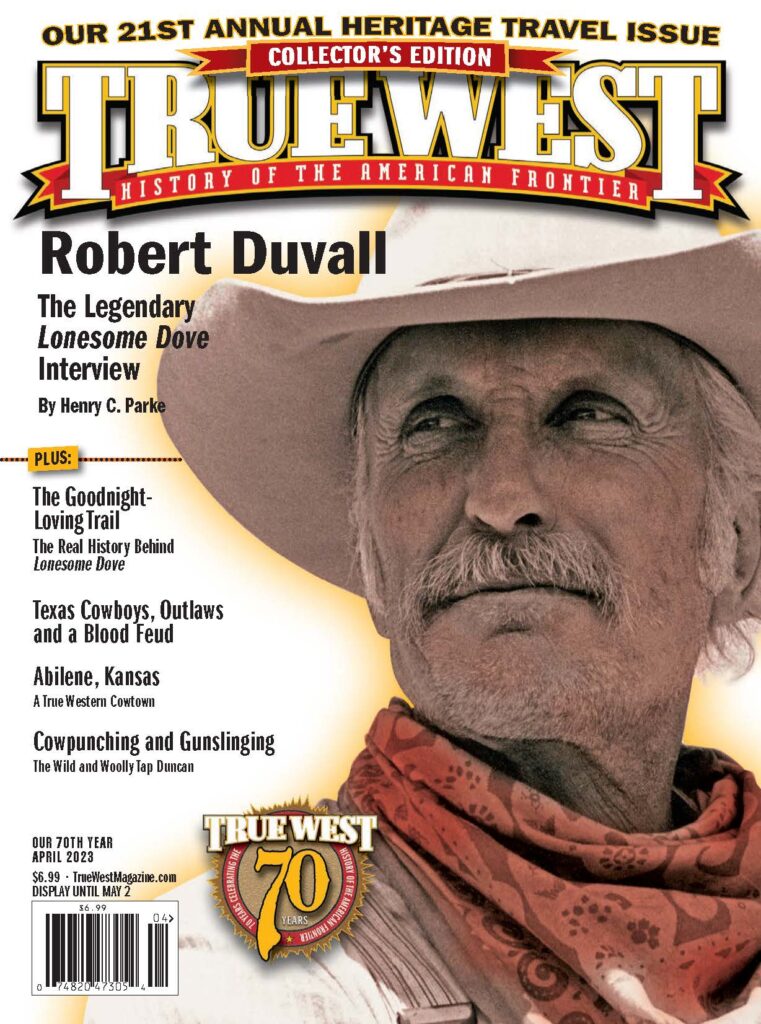

The Goodnight-Loving Trail has inspired songwriters and novelists. Cattleman Charles Goodnight became one of the iconic figures of Texas and the West—and helped save the American bison from extinction. Oliver Loving, whose death in 1867 led to one of Robert Duvall’s most endearing acting roles, has a Texas county and an Eddy County, New Mexico, village named after him.

Goodnight and Loving are credited with blazing the trail to deliver cattle to the Bosque Redondo Reservation at Fort Sumner in New Mexico Ter-ritory in 1866, and the trail eventually stretched to Denver and Cheyenne.

“The trace that led from Texas to Fort Sumner is generally known as the Goodnight Trail, while that which Goodnight later blazed direct to Cheyenne is called the Goodnight and Loving Trail, though sometimes the terms are used interchangeably,” J. Evetts Haley wrote

in Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman (Houghton Mifflin, 1936).

At least, that’s the legend. Two historians, however, have recently suggested that maybe the trail should be known as the Chisum Trail.

Chisum vs. Goodnight & Loving

“Erroneous popular mythology holds that Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving made the first drives across West Texas and up the Pecos River to New Mexico markets in 1866 and 1867,” James Bailey Blackshear and Glen Sample Ely argued in Confederates and Comanches: Skullduggery and Double-Dealing in the Texas-New Mexico Borderlands (University of Oklahoma Press, 2021). “In fact, this route was established prior to Goodnight and Loving and was known as the Chisum Trail decades before Goodnight’s biographer branded it the Goodnight-Loving Trail.”

The authors partially base that argument on an 1897 civil engineer’s map that “labels the cattle route leading from the Concho River watershed to Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River as ‘the Chisum Trail.’”

Doing a scan on Newspapers.com and NewspaperArchive.com, granted, isn’t sound scholarly research, but the earliest findings of Chisum Trail (not including misspellings of the famed Texas-to-Kansas Chisholm Trail) that I found is 1884; Goodnight Trail, 1885; and Goodnight-Loving Trail, 1923. Chisum moved his Texas cattle operations to New Mexico in the late 1860s, basically following much of the Goodnight-Loving route.

“The Goodnight trail was called for the man who opened it and drove cattle over it for years, Charles Goodnight,” the Galveston (Texas) Daily News reported on November 25, 1892. “It started in the country southeast [actually, southwest] of Fort Worth and led southwestward to the Pecos, which it crossed at Horsehead crossing, followed the river up through New Mexico and went over into Colorado, ending near Pueblo.”

West from Texas

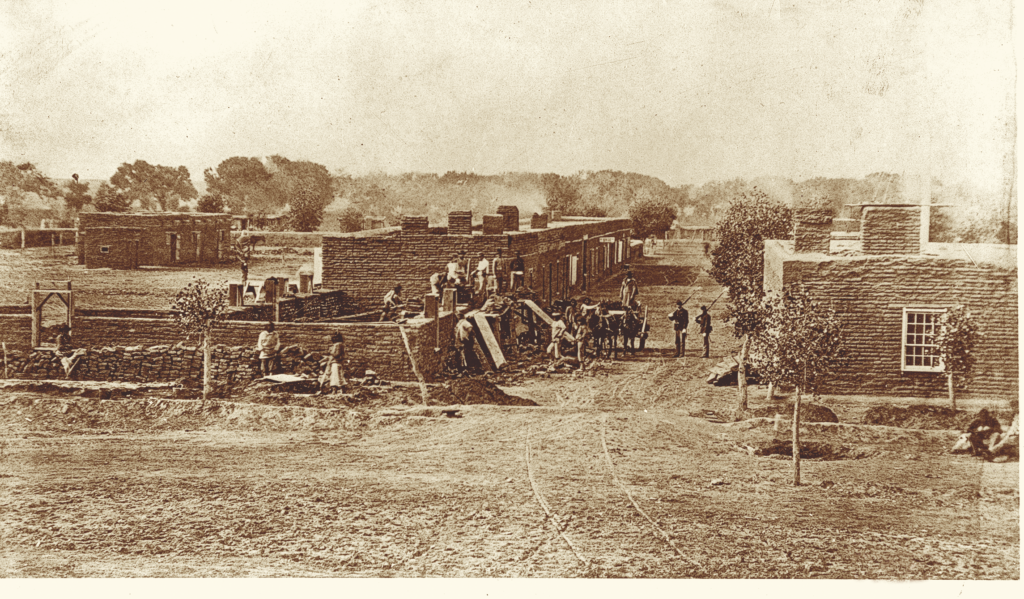

With the establishment in 1863 of the million-acre reservation near Fort Sumner, beef was needed at that remote outpost in present-day De Baca County before 1866. The Santa Fe Gazette ran a notice from the Army’s Department of New Mexico’s chief commissary seeking delivery of “good marketable Beef Cattle” to be delivered to Fort Sumner: 200 by May 31, 1864; 300 by June 30, 1864; and 500 by July 31, 1864.

By then, Chisum was tired of selling beef to the Confederacy. Born in 1824 in Tennessee, Chisum had moved to Texas by 1837, where he worked in Paris as a store clerk. After stints as owner of grocery stores and in politics (Lamar County clerk, 1852-54), Chisum turned to ranching in North Texas, where he lived in Bolivar (near present-day Sanger) from 1856-62. When the Civil War broke out, he was placed in charge of getting herds to the Confederate army along the Mississippi River. Chisum later moved his operations to the Colorado River country east of present-day San Angelo and also ran a store in Trickham, which became a point on the Western cattle trail.

After the fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1863, Chisum learned that selling beef to the Confederacy was a money-losing enterprise. By 1864, a Confederate dollar was worth a dime. “Union contractors,” Blackshear and Ely wrote, “paid in a currency that actually had value.”

Enter Union operators James Patterson, William C. Franks, Thomas L. Roberts and James Conwell. They rode into Texas and, with Chisum’s help, gathered a herd of Confederate cattle and moved them into New Mexico Territory in the spring of 1865. Patterson and his associates weren’t alone. Other Unionists managed to slip Texas beef into Mexico by loosely following John Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company route (September 16, 1858-March 21, 1861). Chisum soon had a New Mexico connection, relocated there, and, Blackshear and Ely wrote, “West Texas cowmen were calling this Texas-New Mexico cattle road the ‘Chisum Trail.’”

Not that it matters because in 1866 Goodnight and Loving teamed up to make history and legend.

A Legendary Partnership

Goodnight was born in Illinois in 1836, and his family moved to Texas when Goodnight was nine, four years after his father’s death. At age eleven, Goodnight started hiring out to farms. He tried other jobs, and in 1856, three years after his mother remarried, Goodnight partnered with his stepbrother, John Sheek, in the cattle business. In 1857, Goodnight and Sheek moved their cattle operation to Palo Pinto County.

Loving, a Kentucky native who moved to Texas in 1843 when he was 30, had driven herds up the Shawnee Trail, and in 1860 he partnered with John Dawson to bring 1,500 cattle to Denver. Commissioned to drive cattle to Confederate forces on the Mississippi River later that year, Loving soon found himself in a situation similar to Chisum’s. The Confederate government reportedly owed Loving between $100,000 and $250,000 after the war.

It was Goodnight’s idea to take a herd to Bosque Redondo, and newspapers had spread word that there was a market for beef at Fort Sumner.

The Office of Supervising Commissary announced that it sought bids for delivery of 6,000 cattle, beginning July 1, “for issue to the Indians on the Bosque Redondo Reservation.”

“The cattle,” the notice in the March 22, 1866, edition of the Leavenworth (Kansas) Daily Conservative read, “must all be weighed upon the scales at Fort Sumner or other point of delivery upon the Reservation, under the personal supervision of the A.C.S. at Fort Sumner, and his certificate of weights must accompany the accounts of the Contractors when presented for payment.”

Goodnight could have asked Chisum for advice. “He was a great trail man,” Goodnight said years later. “No one had any advantage of him as an old-fashioned cowman, and he was the best counter I ever knew. He could count three grades of cattle at once, and count them accurately even if they were going at a trot.”

Goodnight did seek Loving’s input. Loving warned Goodnight of the hardships on such a drive across dry country. Seeing that Goodnight was undeterred, the older cowman said, “If you will let me, I will go with you.”

“I will not only let you, but it is the most desirable thing of my life,” Goodnight replied. “I not only need the assistance of your force, but I need your advice.”

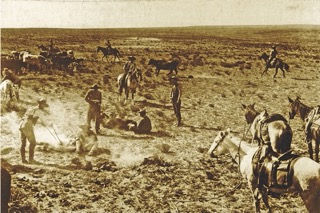

Their herds joined south of Fort Belknap in present-day Newcastle, and on June 6, 1866, the drive of 2,000 cattle and 18 men—including former slave Bose Ikard and “One-Armed” Bill Wilson—started west.

Staying on the Butterfield route, men and livestock trod past Camp Cooper and Fort Phantom Hill and through Buffalo Gap near present-day Abilene, then pushed on toward Fort Chadbourne and the Middle Concho River near present-day San Angelo, where they rested for what lay before them: The Staked Plains.

Beating the Odds

They moved through Castle Gap and, 12 miles later, reached the Pecos River at Horsehead Crossing and the country Goodnight called “the graveyard of the cowman’s hopes” and “the most desolate country that I had ever explored.”

Pushing north, they crossed the Pecos River at Pope’s Crossing, not far from the New Mexico border. The crossing vanished with completion of Red Bluff Damn and Reservoir in 1936.

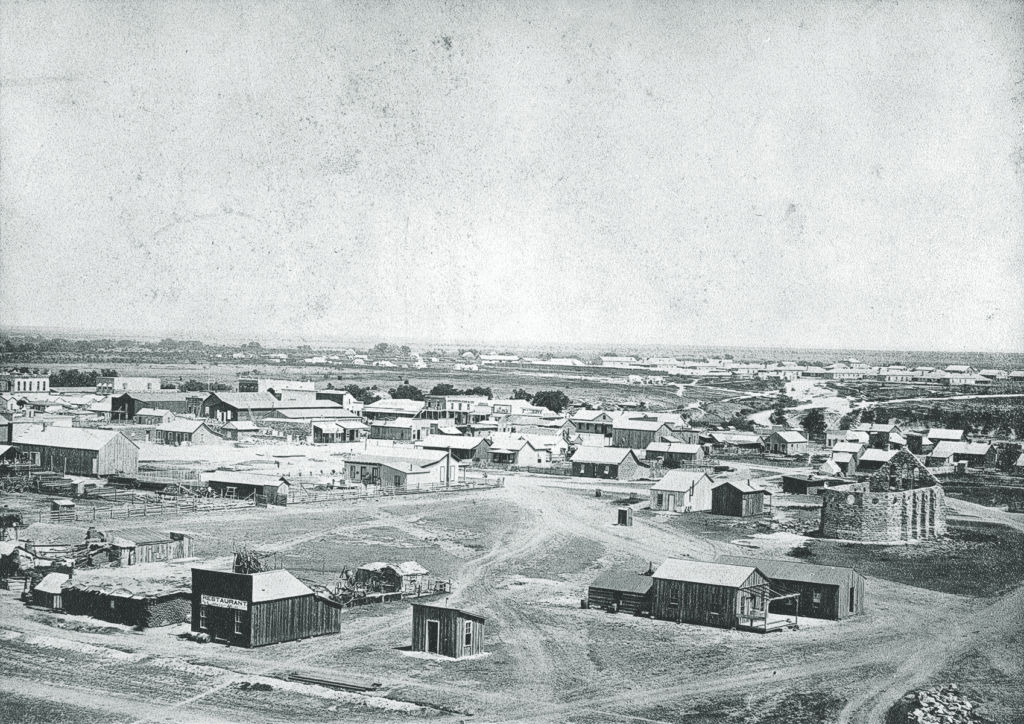

“Immense numbers of cattle are now in this Territory and many more are en route from Texas,” The (Santa Fe) New Mexican reported on July 21, 1866. “We hear many rumors about the beef contract at the Bosque, and some who are not aware how things are managed in this country, will be enlightened by the developments that will be made as soon as facts and figures can be gathered.”

Goodnight and Loving learned how things were managed when they reached Fort Sumner. Government contractors bought only steers, and the Texans had driven a mixed herd. You’d think that, if indeed Goodnight sought out Chisum’s advice, ol’ John would have mentioned the fact that Sumner was a steer-only market. Maybe he did. Maybe Goodnight and Loving also had eyes on the northern plains.

They sold the steers at Sumner for $12,000, and Goodnight returned to Texas, while Loving and his crew pushed the 700 to 800 remaining cattle to Denver. There, John W. Iliff, called the “Cattle King of Colorado” when he died in 1878, bought the herd.

The Goodnight-Loving partnership was strong, so they drove another herd in 1867, taking the same route. Loving might have thought it was a good time to get out of Texas.

A notice in the Dallas Herald said the Parker County sheriff directed Loving to appear in district court in Weatherford in August after Robert E. Bell filed a petition against Loving and his son, James, alleging that Bell was owed $1,432.92 for cattle that had been delivered in October 1866. “Said amount is now due and unpaid, for which [Bell] prays judgment against said defendants for said debt and costs of suit.”

By the time that notice appeared in the press, however, Loving was dead.

Riding ahead of the herd to initiate contract bidding at Sumner, Loving and Wilson were attacked by Indians in southern New Mexico. Loving was wounded, so he sent Wilson for help—which gave us Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove and made Duvall the favorite trail boss and ex-Texas Ranger of many Americans. A group of Hispanic traders found the wounded Loving and brought him to Fort Sumner, where he died from gangrene on September 25.

Goodnight pushed the herd into Colorado, where he began a ranch and cattle-relay station near Trinidad. In 1868, Goodnight returned to Fort Sumner, loaded Loving’s coffin into a wagon and brought him back to Texas for burial—in Weatherford’s Old City Greenwood Cemetery. Haley called this bit of legend “the strangest, and most touching funeral cavalcade in the history of the cow country.”

Bose Ikard, who died in 1929 at age

85, is buried nearby, complete with Goodnight’s praise: “Served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches. Splendid behavior.”

North to Wyoming

Later in 1868, Goodnight contracted with Iliff to drive cattle to the Union Pacific Railroad

in Cheyenne, Wyoming, extending the Goodnight-Loving Trail again: to Pueblo, east of Denver to the South Platte River, past Greeley and then along Crow Creek to Cheyenne. To save the expenses of Uncle Dick Wootton’s toll road and avoid rugged Raton Pass, Goodnight later moved the trail through Trinchera Pass, not far from Capulin, New Mexico.

But Goodnight and Loving (and Chisum) weren’t the only cattlemen who would follow their trail. “By 1870,” Haley wrote, “the trade along the Goodnight and Loving Trail was well established, and the amount of money handled by its Western bankers was noted as enormous.”

In 1885, Kansas closed its borders to Texas cattle drives, and with ranges in Colorado and points north needing cattle, the trail became a popular route through Texas and New Mexico.

Popular with Texans anyway. Not necessarily non-Texans.

“The Northern New Mexico association have pledged themselves to see that no cattle are trailed from Texas northward west of the old Goodnight trail,” the Galveston Daily News reported July 24, 1886, “and will institute trespass proceedings against all herds found on the range of any of its members after today.”

Not that it mattered.

“The Big Die-Up”—that tragic winter of 1886-87— killed hundreds of thousands of cattle, especially on the northern ranges. After that, lower railroad shipping rates and more efficient range management took over.

Long cattle drives and trails like the Goodnight-Loving, Goodnight, Chisum, or whatever you want to call it, became a part of Western legend and history.

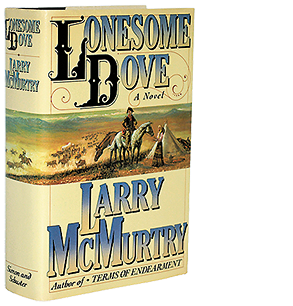

Lonesome Dove: Larry McMurtry’s American Masterpiece

In 1985, Texas author Larry McMurtry published his 11th novel and 12th book, Lonesome Dove. Nearly four decades later, the Pulitzer Prize-winning bestseller is considered one of the greatest and most popular American novels of all time. What many may not remember is that it was also a major turning point in McMurtry’s life and writing career. Up to that year, the Archer City, Texas, native was best known as a novelist of the 20th-century West. Like his Western peers Max Evans, Jim Harrison, Ivan Doig, Thomas McGuane and J.P.S. Browne, he mined his own experiences and life to write about the West he knew and loved.

He had also found fame as a screenwriter and competed for national headlines in Hollywood and New York with contemporaries Tom Wolfe, Pat Conroy and Ken Kesey. He had transcended the label Western writer—until he wrote Lonesome Dove—his first 19th-century Western novel. And while an 843-page novel cannot be considered a whim, McMurtry himself never considered it as great an American novel as it is. He was even quoted as saying it was “the Gone With the Wind of the West, which is good and bad.” I would challenge McMurtry’s modesty and suggest that in the pantheon of American literature, Lonesome Dove should be side-by-side with James Fennimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!, Edna Ferber’s Cimarron, John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose and—of course—Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind!

—Stuart Rosebrook