– Courtesy Library of Congress –

They were more than the sum of their parts, 19th-century surveyors, the unheralded vanguards of the Old West who established original geographical boundaries and retraced and identified existing borders in accordance with legal descriptions. Part-astronomers, part-geologists, part-engineers, these mapmakers were also arbitrators when land lines were in dispute. Wars have been fought and people killed over boundary disputes in which the surveyor was often the common denominator.

Yet only a handful of surveyor names remain familiar: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and Daniel Boone. But many more risked their lives in the line of duty to map what ultimately became the passes, railroads, towns, dams and other structures that helped form the backbone of the West.

The face and persona of our Westward Expansion, surveyors shaped Western history through their endurance, sense of adventure and knowledge of precision tools and mathematical principles.

Jacks of All Trades

“The early surveyors required the skills of a woodsman to blaze trails, and agronomist or mineralogist skills to document the soil structure or important minerals…[and] knowledge of botany to document the species of trees and determine the difference between plants that were edible and those that would kill them. “Good marksmanship was needed to obtain fresh food on site, and to defend against hostile Indians,” wrote Nebraska surveyor Jerry Penry, in The American Surveyor, a national trade journal for his profession.

“Perhaps no other occupation in history has required the worker to encompass so many different areas of expertise as the American surveyor,” he theorized.

The job was hard; the perils many. One of the earliest accounts of surveyors killed took place in 1838, just two years after the Battle of San Jacinto, when Texians defeated Mexican Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna. On the Guadalupe River north of San Antonio, Indians attacked a survey party and killed nine of the crew, including one surveyor who managed to carve his name, “Beatty,” on a tree before he died. At least seven more survey parties were attacked that spring and summer, from the Rio Frio to the Red River.

Henry P. Mayo, a third-generation Texas surveyor, is a member of the Surveyors Historical Society. He helped research and compile A Marylander and Texian: H.G. Catlett’s Quest for Fortune in Early Texas, in which noted Texas surveyor H.G. Catlett tells his story of early surveys through central Texas, as well as his exploits as a Texas Ranger. Rangers often conducted land surveys during the early years of Texas settlement.

“Despite attempts to prevent surveys on Indian hunting grounds, the incursions continued,” Mayo says. “In March 1838, a deputy surveyor planned surveys on the headwaters of the Navasota River. Kickapoo Indians attacked his group, killing three men.

“As a modern-day surveyor, I often relate to these pioneer surveyors. Fortunately, today, we don’t have to fight Indians, only local citizens who protest the end of their quiet country living.”

Building the Railroad

Arguably, the most important role that surveyors played in developing the West took place during the building of the 1,776-mile-long Transcontinental Railroad, completed on May 10, 1869.

In his acclaimed book, Nothing Like It in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, 1863-1869, Stephen E. Ambrose called pioneer surveyors the true “…mountain men, adventurous, capable of taking care of themselves, ready for whatever the wilderness threw at them…. Nothing could be done until they had laid out and marked the line.”

Though some were self-employed contractors who surveyed in temporary positions—unregulated and unlicensed—others were hired by the government. Route surveyors established alignments for railroads and roads. Those who worked for the General Land Office (now known as the Bureau of Land Management) stayed in confined areas as they divided up townships and individual tracts of land. Construction surveyors determined the best locations and elevations on which to build.

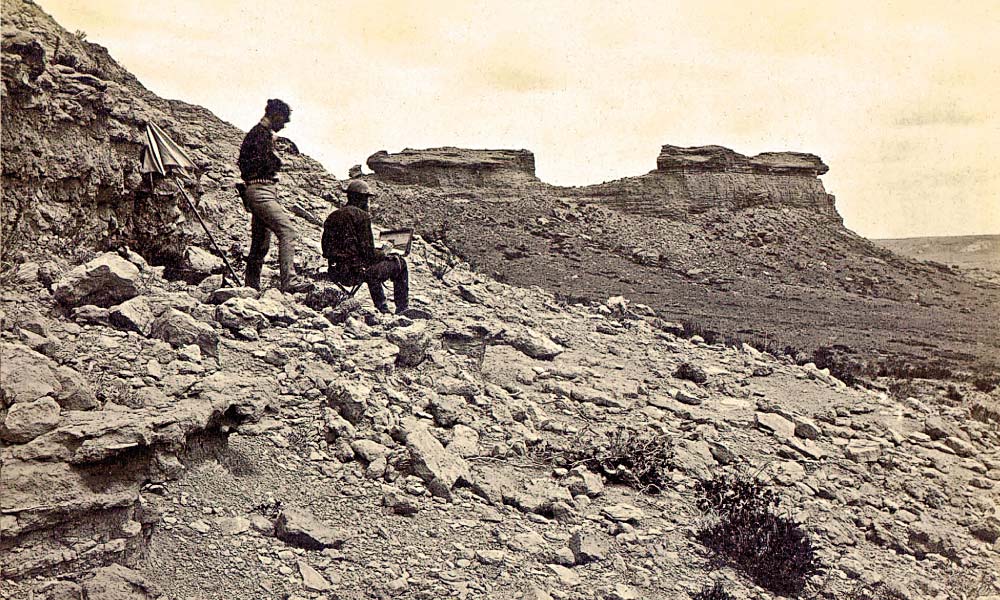

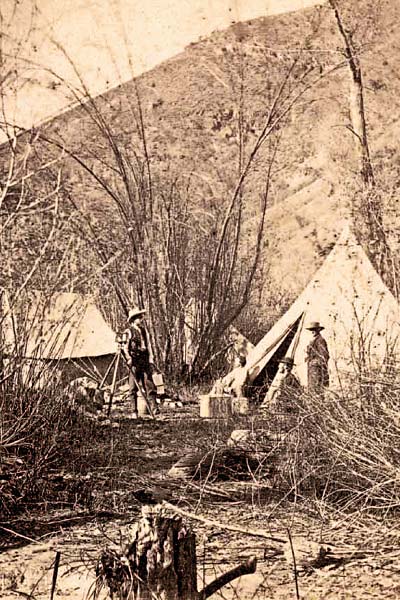

The business typically consisted of a lead surveyor, “chainmen” (a chain was a measuring device, with 100 links, totaling 66 feet in length), a flagman and cornermen (they marked the end of section lines), plus a teamster to handle the wagons and horses, and a cook. Most surveyors were young, physically able men who labored, traveled, ate and camped together for weeks on end.

Their equipment, loaded in wagons or carried on horseback, included blankets, tents, survey chains, monuments (today known as stakes), a transit (similar to a telescope) and a tripod, six-shooters, rifles and ammunition, a chronometer for accurate time, if lines of longitude were needed (a north-south state line, for example), and a compass.

Enough surveyors died at the hands of Indians during the building of the Transcontinental Railroad that survey parties were advised to wait for military escorts. Native tribes viewed these European “measurers” as a primary cause for the land disappearing out from under them.

Buck’s Last Line

As for the surveyors, the “Indian menace” was a genuine threat. Cheyennes, Arapahos, Sioux, Pawnees and Kickapoos roamed the region over hunting grounds that whites were determined to grab and develop. One renowned case in 19th-century Nebraska history became known as the “Nelson Buck Massacre,” an incident in which a surveyor and his party disappeared in July 1869 and were never seen alive again.

After Nebraska Territory entered statehood in 1867, Buck waited two years for the federal government to award the Illinois surveyor the contract. His job was to survey Red Willow and other Southwestern counties in Nebraska Territory in order to confirm the Kansas-Nebraska boundaries.

While out scouting, crew members spotted a band of Indians, killing three in what appeared to be an unwarranted attack. One of the crew was also killed. An Indian escaped, reporting the murders to his tribe, which set a chain of retaliatory events in motion.

Over the next few days, the Indian band pursued what remained of the survey crew, taking their horses, their rations and destroying two wagons, as well as killing five white men. Buck’s remains were later identified by his saddle and revolver—his name was inscribed on the weapon.

Though historians say Buck and his crew made errors in judgment, including underestimating dangers from Indian attacks, the tragedy continues to be commemorated in Nebraska’s surveying history.

“Theirs was a hard life with a tragic ending,” the plaque reads today, set alongside Nebraska Highway 89 near Marion, within a mile of the massacre site, by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Resilient and Tough

Daily conditions in the field were fraught with hardship. Fresh water was almost always in short supply. The grub was “poor and without variety,” according to journal accounts, unless the men could hunt for meat after a day’s work.

Ira Cook, a deputy surveyor in Iowa from 1849 to 1853, described his resting place after a long day, when the surveyors were too worn out to construct shelter: “My own bed was at the foot of an oak tree, using the root for a pillow…I thought it rather tough, but I soon got used to that sort of thing.”

Early Nebraska surveyor Harley Nettleson stated, at times, the men worked all day without food. Surveying in the wilds in 1883, he reported that several of the men were sick from drinking alkali water. He added, “…sometimes [we] had nothing to eat until evening. Food consisted of beans, rice, salt pork or bacon, biscuits, and coffee.”

Along with laboring six to seven days a week and walking up to 20 miles a day, surveyors dealt with not only Indian attacks but also wild animals, venomous snakes and serious accidents, though each hazard was understood as a normal part of the job.

Land surveyor Rollin C. Curd, now in his 90s and living in Nebraska, wrote A History of the Boundaries of Nebraska and Indian Surveyor Stories, in which he describes the type of men who joined a 19th-century survey party in western Nebraska: One was an attorney who came west to “make a fortune” and study law privately, but had joined the crew for the adventure; another had been a schoolteacher. One was just out of college and deemed a tenderfoot. A particularly nervous crew member quit after 30 days, saying he was concerned his scalp would end up dangling on the end of an Indian belt.

Nebraska’s first state surveyor, Robert Harvey, recalled an incident when the men feared for their lives. In August 1872, the crew was surveying township lines in Custer County, near the South Loup River. They had seen signs of Indians and had selected a marshy camp they could defend, reasoning that the natives couldn’t surround them or cross the marsh.

“While the cook was getting dinner, I looked across the valley to the west and saw a head pop up…then another and another, until several Indians on ponies appeared on the ridge,” Harvey remembered. “…They had seen us…[a] force of five men were set to digging rifle pits around the wagon…. The men with the spades were throwing up earth and going into the ground like badgers….”

One of the surveyors took off, much to Harvey’s disappointment, as even the loss of one man could prove disastrous. Harvey found him in the river, changing clothes.

“If there’s to be any killing around here,” the surveyor explained, “I don’t want to be found dead in old ragged overalls….”

As the survey crew prepared to fire on the intruders, Harvey called “Halt!” The believed hostiles were actually Indian soldiers, part of the cavalry camped a mile or two down the river. They had mistaken the survey crew for elk.

The Tradition Continues

Contemporary surveyors maintain an appreciation for their predecessors. To raise awareness of the contributions surveyors made to the West, Montana surveyor Kurt Luebke helped re-create an authentic survey campsite, using 19th-century artifacts, in Bannack State Park.

“We believe surveyors were instrumental in leading the way for U.S. history,” he explains. “They helped provide an organized and civilized settlement as each new frontier opened, while the mapping of rivers, trails, waterholes, forts and settlements allowed people to travel as safely and efficiently as possible.”

Arizona surveyor Rick Bunger collects statewide survey histories, conducts interviews with old-timers and plans on writing a book about the contributions surveyors have made to Arizona history.

Denny DeMeyer, PLS, a land surveyor in Blaine, Washington, and co-chairman of North American Land Surveyors, says, “Everything ahead of society was done by surveyors. No government land was sold, no towns or cities platted, no railroads, canals, irrigation channels, roads constructed or mines developed without them.”

Garland Burnett has spent more than 40 years in land surveying and is recognized as an expert witness in ancient boundary cases for New Mexico courts. At one point, he worked for the U.S. Forest Service and became familiar with 19th-century surveyors whose work he retraced.

“It’s a complex and confusing profession to most people,” he says. “Our work is somewhat esoteric unless you have some knowledge of math, computer science, geology, history, astronomy and real property law, to name a few. But if you don’t know what happened in the past, you can’t determine what’s needed in the present.”

Land, boundary and title consultant James R. Dorsey, PLS, spent more than half a century in surveying, specializing in wetland boundary problems in the Western states. Now retired and living in Nevada, he is an author, lecturer and instructor. Dorsey believes that without the orderly location of land by surveyors, range wars would have been even worse, with a “strongest-take-all” attitude.

“The contribution by surveyors goes all the way back to our Founding Fathers when they said that all men are created equal,” Dorsey says. “Without that mandate and the definition of private ownership land, along with the Homestead process that was part of the land survey system by the government, there would have been no migration west—at least nothing orderly.”

– All images courtesy Denver Public Library unless otherwise noted –

Marie Bartlett is a North Carolina-based freelance writer, a former member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and a current member of Western Writers of America.