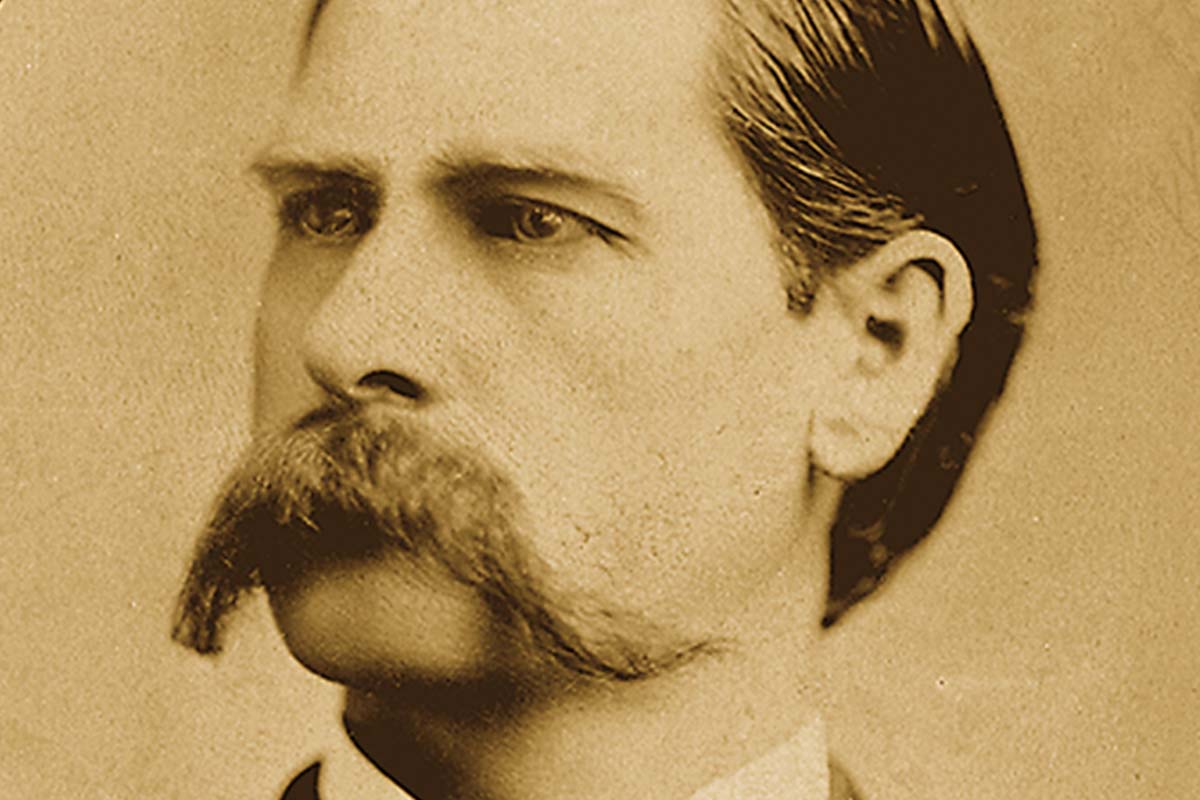

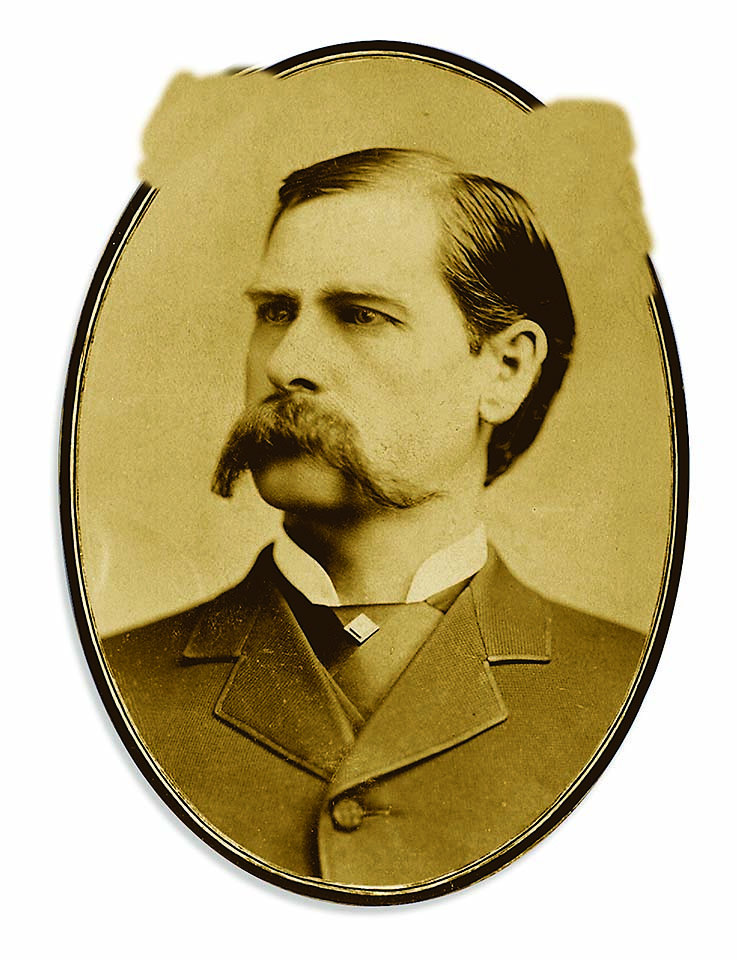

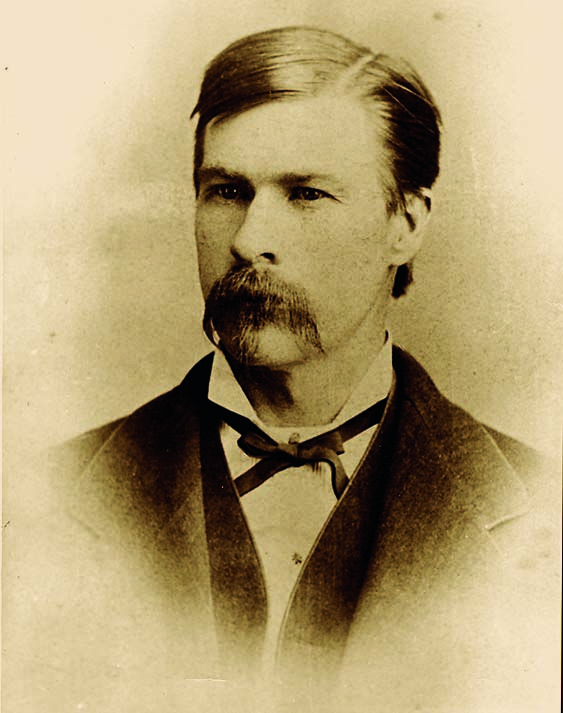

Wyatt Earp, who has become controversial since his fictionalization by television, did serve in both Dodge City and Tombstone as a legally appointed deputy marshal. True West presents the proof with these findings of a revealing probe into government records and the words of a man who knew Earp personally.

The question of whether Wyatt Earp was a bona fide U.S. marshal or an imposter has been asked many times and still is being asked by readers of True West and Frontier Times.

Just what are the facts that lie behind the mystery of the badge Earp wore while in Tombstone?

Some are of the opinion that doubt about Earp’s legal status grew out of Stuart N. Lake’s biography, Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal. Although Lake may have gone astray on some of his material, he can hardly be blamed for the story that Earp was a fraud, legally at least. There are more than 20 books bearing copyright dates from 1907 to 1959, and somewhere in most of them will be found a hint that Earp’s status quo may have been in doubt. Only one, however, comes right out and says such was the case. The others make some mention of it but never go so far as to seriously question Wyatt’s legal status.

It is true that there is no record at the Department of Justice in Washington to show that Earp was ever a U.S. marshal. But that proves nothing. Back in the late seventies, U.S. marshals came and went, and how long each stayed on the job depended usually on how many politicians he knew. No accurate record of the appointments was kept until along toward the turn of the century when the business of selecting marshals was systematized.

One night last fall, I was reading Pat Jahns’ biography of Doc Holliday. In his book, Jahns quotes a telegram from Marshal Crawley P. Dake to Acting Attorney General S. F. Phillips. This telegram, while it calls no names, is quite evidently a short report on the 0.K. Corral fight, and Dake speaks of “my deputies.” This could only have been a reference to the Earps.

After having read this, I wrote a letter to the Department of Justice to see if this telegram was authentic. The letter was referred to the National Archives for an answer. From a report written in 1941 by Frank D. McAllister, an employee of the National Archives, I began to comprehend the true picture.

McAllister’s first paragraph explains why there is no record of Earp in the Justice Department. Until 1896 the Department of Justice did not keep a systematic record of deputy U. S. Marshals. Some were recorded, but a larger number were not. In 1896 the fee system was abolished and this was changed. While there is no reference to Wyatt Earp by name, there are several references to the Earp brothers.

The earliest of these references is dated November 17, 1881. It is a letter from S. F. Phillips to Crawley P. Dake concerning one of Dake’s deputies, a “Mr. Earp” of Tombstone. According to this letter Earp “…is disposed rather to quarrel with the Territorial authorities than to cooperate with them.”

On December 5, 1881, Marshal Dake sent the following letter to Attorney General Phillips, in connection with the gunfight at the 0.K. Corral:

“…the Sheriff of Cochise County in which Tombstone is situated, attempted to interfere with the Messrs. Earp and their assistants (Marshal Dake’s deputies) but the attempt has completely failed. The Earps have rid Tombstone and neighborhood of the presence of this outlaw element. They killed several cowboys in Tombstone recently and the Sheriff’s faction had my deputies arrested and after a protracted trial my deputies were vindicated and publicly complimented for their bravery in driving this outlaw element from this part of our territory. The Magistrate discharged my deputies on the ground that when they killed Clanton and the McLowerys they were in the legitimate discharge of their duties as my officers. Hereafter my deputies will not be interfered with in hunting down stage robbers, mail robbers, train robbers, cattle thieves, and all that class of murdering banditti on the border.

“I am proud to report that I have some of the best and bravest men in my employ in this hazardous business—men who are trusted and tried, and who strike fear into the hearts of these outlaws.” (Department of Justice Files, Arizona)

According to this letter all of the Earps were federal lawmen. One might even say that Doc Holliday was also a deputy U. S. Marshal.

Earlier in 1881 (November 28th) Acting Territorial Governor John J. Gosper wrote a letter to Marshal Dake about the problem in Tombstone. The letter read: “Another cause of the troubles alluded to is the fact that the present Sheriff of Cochise County and one of the Earp brothers, not your deputy, but a brother to the latter, being in some matter connected with the police force for the City of Tombstone, are candidates or aspirants for the sheriffship at the polls another season; the rivalry between them having extended into a strife to secure influence and aid from all quarters has led them and the particular friends of each to sins of commission and omission greatly at the cost of peace and property.” (Enclosed in letter to S. F. Phillips from C. P. Dake, December 8, 1881. Department of Justice Files, Arizona.)

Anyone with a reasonable knowledge of the history of Tombstone will immediately recognize the brother spoken of as Wyatt Earp.

In any of these reports the deputy marshal Earp could have been Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan or all three. According to the District Clerk’s office in Tucson, Virgil Earp took the oath of office as a deputy U.S. marshal on November 27, 1879. If, as the letters seem to indicate, Morgan and Wyatt were federal lawmen, their appointments must have come sometime in 1881.

On March 18, 1882, Morgan Earp was murdered while playing pool with Bob Hatch in Hatch’s billiard parlor. There is nothing in the newspaper account to tell us anything about Morgan’s official status at the time of his death. Although the records are missing, the Subject Index of the Department of Justice lists a letter which tells of the murder of Deputy U. S. Marshal Earp. Only Morgan Earp was killed while in Tombstone, so this letter evidently referred to Morgan.

In April of 1882 the Department of Justice sent a Special Agent to investigate the conditions of Marshal Dake’s office. In his report the Agent stated:

“He (Dake) retains upon his force as Deputy one of the Earp boys of Tombstone who is now an outlaw and with others is hiding in the mountains awaiting their time for a big fight in Tombstone.” (Department of Justice Files of the Appointment Clerk, “Confidential Report of S. R. Martin, Special Agent, April19, 1882, on Marshal Dake.”)

This report could refer to only one of the Earp brothers, Wyatt. Morgan was dead and Virgil was in California recovering from his wounds. Warren Earp was with his brother, but in the face of Warren’s youth and inexperience, Dake would have hardly chosen him as a lawman over his brother Wyatt.

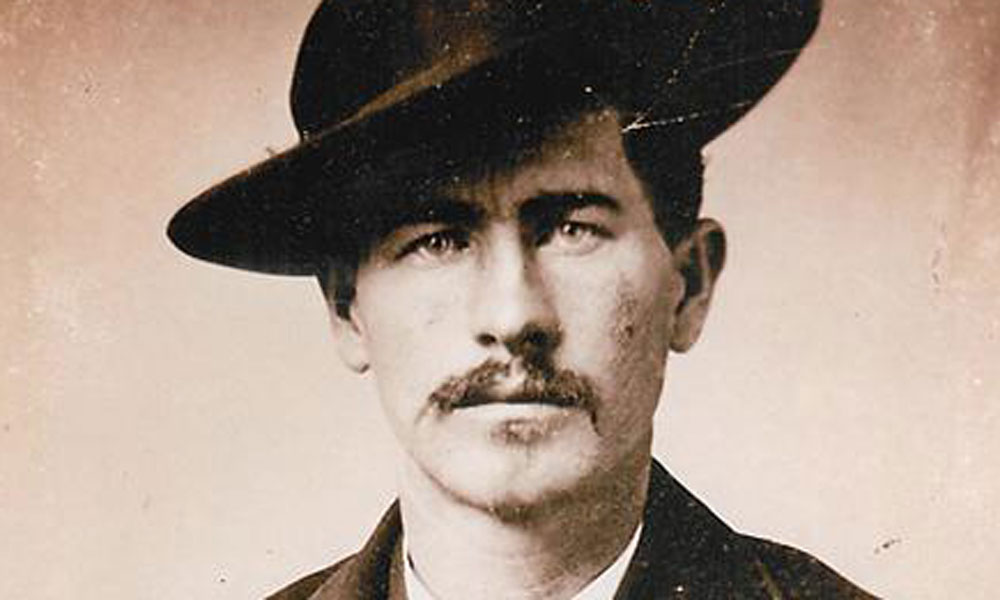

– Photos and Illustrations Courtesy True West Archives –

From this information it seems that Virgil, Wyatt and Morgan were all deputy U.S. marshals. Virgil went to Tombstone as a deputy U. S. marshal since he took the oath of office in Yavapai County just a few days before he moved to Tombstone. Morgan and Wyatt were later appointed to work with their brother. After Virgil was wounded and Morgan was murdered, Wyatt remained to avenge the death of his brother.

From the evidence available in the National Archives, coupled with that in the District Clerk’s office in Tucson, we see that the Earp brothers had federal authority from first to last in Tombstone.