– All photos True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

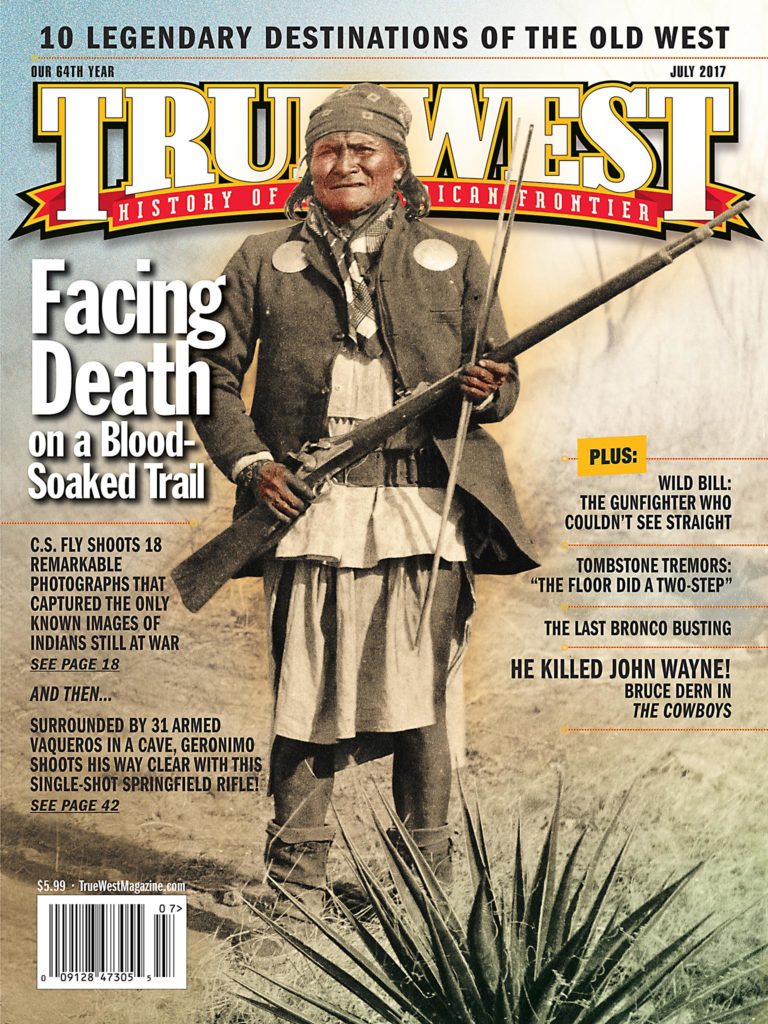

In the middle of March 1886, Camillus Sydney Fly, perhaps Arizona’s best-known frontier photographer, loaded his camera, camping gear, provisions and a box or two of pre-sensitized eight-by-10-inch glass photographic plates onto pack animals and departed his Tombstone studio, accompanied by his assistant, a Mr. Chase. Fly was hoping to catch U.S. Army Gen. George Crook at Silver Springs on his way to the expected surrender of the renegade Apache chief Geronimo and his followers.

After an encounter with American forces several months earlier in the Sierra Madre Mountains of northern Mexico, Geronimo had unexpectedly offered to meet with Gen. Crook, who commanded the Military Department of Arizona and was well-respected by the Apaches. Word soon spread of the upcoming conference, and Fly wanted to record it on film.

Geronimo had declined to meet Crook on American soil, fearing American treachery, and chose Cañon de los Embudos (translated as “Canyon of the Funnels”) in northeastern Sonora, Mexico, as the meeting location.

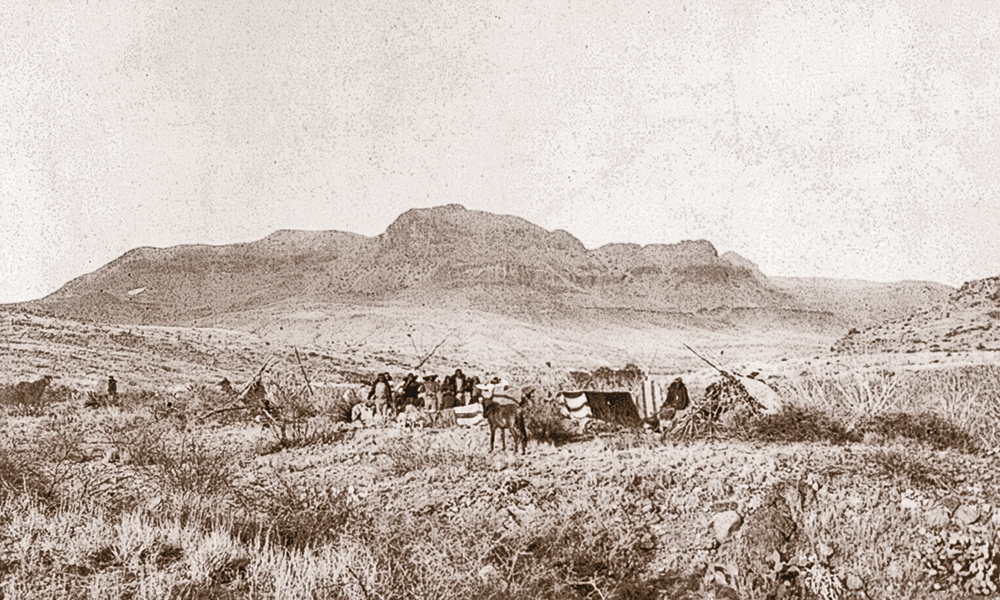

After a January meeting with Geronimo to make preliminary arrangements, Lt. Marion Maus marched his men about 80 miles north to the mouth of Embudos canyon on San Bernardino Creek, about 14 miles south of the international boundary. Maus established a camp there and waited until the arranged meeting time in March, watching for smokes from the Apaches that would signal their readiness for the summit.

When smokes were observed and Apaches were spotted in late March, Maus sent a message to Fort Bowie for Crook and then moved his camp up to where Embudos Creek emerged from the mountains.

After receiving word, Gen. Crook and several companions headed south from Fort Bowie, along the western slope of the Chiricahua Mountains, on a 50-mile, two-day ride to Silver Springs. Fly met the general at that camp site on the evening of March 23 and secured permission to follow along behind the column to record the momentous occasion for posterity.

Beyond John Slaughter’s ranch headquarters, the military party traveled on a road that crossed the unfenced U.S.-Mexico border into Sonora, passed the ruins of the old hacienda of the original San Bernardino Land Grant, crossed Cooke’s Wagon Road and continued south, paralleling the flowing San Bernardino Creek.

Three miles south of the border, on March 24, the troops stopped at Contrabandista (translated as “Smuggler”) Springs and made camp. At this spring, probably modern El Ojito, was a makeshift store run by a Charles Tribolet, an unscrupulous U.S. Army beef contractor. Tribolet’s most profitable merchandise was not beef, but tobacco, mescal and whiskey.

The following morning, Crook’s party left the valley of San Bernardino Creek and headed southeast toward the meeting place. They crossed the canyons of Guadalupe Creek and Bonito Creek, and reached Embudos Creek, near where it flowed out of the Sierra los Embudos. Here, Embudos Creek was bounded on the south by lava buttes that rose sharply from the canyon’s edge. The Apaches had chosen their campsite on the upper slopes of these buttes, where they could see approaches from all directions and could easily melt into the mountains behind at the first hint of treachery. Geronimo had chosen a campsite, on lower ground, for the U.S. Army, on the opposite side of the creek.

The first meeting with Geronimo took place on the afternoon of Crook’s arrival, March 25. When Fly whipped out his camera, he saved for posterity the only known images taken of American Indians during wartime, which are published below.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy C.S. Fly’s Photographic Gallery, Tombstone, AZ –

– Courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution –

–Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Library of Comgress –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society 78151 –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Aftermath

When Fly completed his photography on the morning of March 26, he packed up his gear and left for Tombstone, about 80 miles away. Within a couple of days, he had prints made and for sale.

Back in the mountains, things were not going as well. Crook had met with Geronimo on the afternoons of March 26 and 27. At length, Geronimo agreed to bring all of his people in to surrender at Fort Bowie in a few days. When Crook left Embudos early on March 28 to return to Fort Bowie, the situation was already deteriorating. The Apaches had been heard carousing the night before under the influence of Tribolet’s liquor.

In the very early morning hours of March 30, Geronimo and his party rode silently back into the mountains. They continued raiding in Arizona and New Mexico Territories and in Sonora, Mexico, for several months before finally surrendering to Gen. Nelson Miles at Skeleton Canyon on September 4, 1886.

Cartographer Tom Jonas specializes in 19th-century trail research in Arizona

and the Southwest, cartographic analysis and custom historical mapping.