– True West Archives –

Whiskey’s role in shaping the West, and its rise to prominence over rum or vodka, has its roots in the early days of the United States. Its story began with early colonists who learned to distill spirits from their new agricultural bounty of corn, wheat, barley and rye. That continued with our founding fathers, which led to the Whiskey Rebellion. Whiskey also has strong ties to early explorers, mountain men, pioneers, the railroads and more. It was sold as medicine, used to barter with, and fueled the temperance movement. Because whiskey’s main ingredients were easily grown all over North America, the art of distilling spread as rapidly as settlers into newly settled regions. Whiskey was quick and easy to produce, and distilling grains into alcohol made them more valuable, more transportable and more easily stored for long periods. The popularity of whiskey grew, and as whiskey’s popularity increased, so did its value as a trade good.

– Photo by Ernest J. Bellocq, True West Archives –

Whiskey on the Frontier

Early explorers Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and Zebulon Pike took whiskey along with them on their expeditions. In addition to its being a standard Army ration, it was used as a reward for their men and for trading purposes. By the time Lewis and Clark set off on their expedition, the Indians along their planned route were already accustomed to the use of whiskey as a trade good and—in fact—demanded it. French Canadian traders had already established the whiskey negotiation as part of their regular commerce with the tribes they encountered. Major Thomas Biddle, who would be on the later Yellowstone Expedition up the Missouri, wrote, “So violent is the attachment of the Indian for it [liquor] that he who gives most is sure to obtain furs, while should anyone attempt to trade without it, he is sure of losing ground with this antagonist. No bargain is ever made without it.”

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Later, trappers like Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, James Beckwourth and Jedediah Smith carried it with them as a trade good after they, too, learned that the Native peoples wouldn’t trade with them if they didn’t include whiskey in the bargaining process. Beckwourth recalled a trading rendezvous: “The absent parties began to arrive, one after the other, at the rendezvous. Shortly after, General Ashley and Mr. Sublet [Sublette] came in, accompanied with three hundred pack mules, well laden with goods and all things necessary for the mountaineers and the Indian trade. It may well be supposed that the arrival of such a vast amount of luxuries from the East did not pass off without a general celebration. Mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent, were freely indulged in. The unpacking of the medicine water contributed not a little to the heightening of our festivities.”

Missouri played an important role in the settling of the West. It served as a starting point for traders and pioneers in wagons where goods of all kinds were shipped up the Missouri River to the West, and it served as a major hub for the whiskey business. It’s where most of the emigrant trails began, including the Santa Fe and Oregon. As a flood of emigrants rolled their wagons, handcarts and livestock across the West, the lives of the peoples who already called the West home would never be the same. Whiskey’s popularity as a trade good made it an essential tool in opening up new territory, but its influence compounded the damage that was emigration’s legacy for Native peoples. In 1833 whiskey was trading at $5 per pint or $40 per gallon—the cost for whiskey in New York was between $29 and $36 per gallon. (In today’s money, $40 would be about $990.) Supply and demand ruled, and whiskey became a hot commodity. Distillers and others in the business in Missouri enjoyed a good trade in the late 1860s and early 1870s because they were able to ship products to many western cities from the port city of St. Louis.

The Insatiable West

As whiskey became more profitable as a commodity, producers had a hard time keeping up with the demand. Businessmen who wanted to turn a quick profit and fill their coffers created “rectified” whiskey products that were watered down or doctored with other cheaper ingredients like tobacco juice, kerosene, or grain alcohol—hence the term “rotgut.” Straight whiskey was aged in new oak barrels for a minimum of two years, whereas rectified whiskey was usually consumed immediately, requiring no aging, and was often further distilled. Many whiskey peddlers and saloon owners made their own version of whiskey. Elixirs and bitters were also available and were another common way that both men and women pioneers could get drunk.

With its value as a trade commodity firmly established in the West, it was only natural that as the frontier expanded so did whiskey-based entrepreneurship. Pioneers opened a variety of whiskey-related businesses, and a host of other enterprises were formed in the West to support its swelling population. Businesses like stagecoaches, freighters, glass and bottle companies, barrel makers, distributors, hotels, railroads, cities, gamblers, distillers, mining, salesmen and saloons all thrived because of whiskey.

– True West Archives –

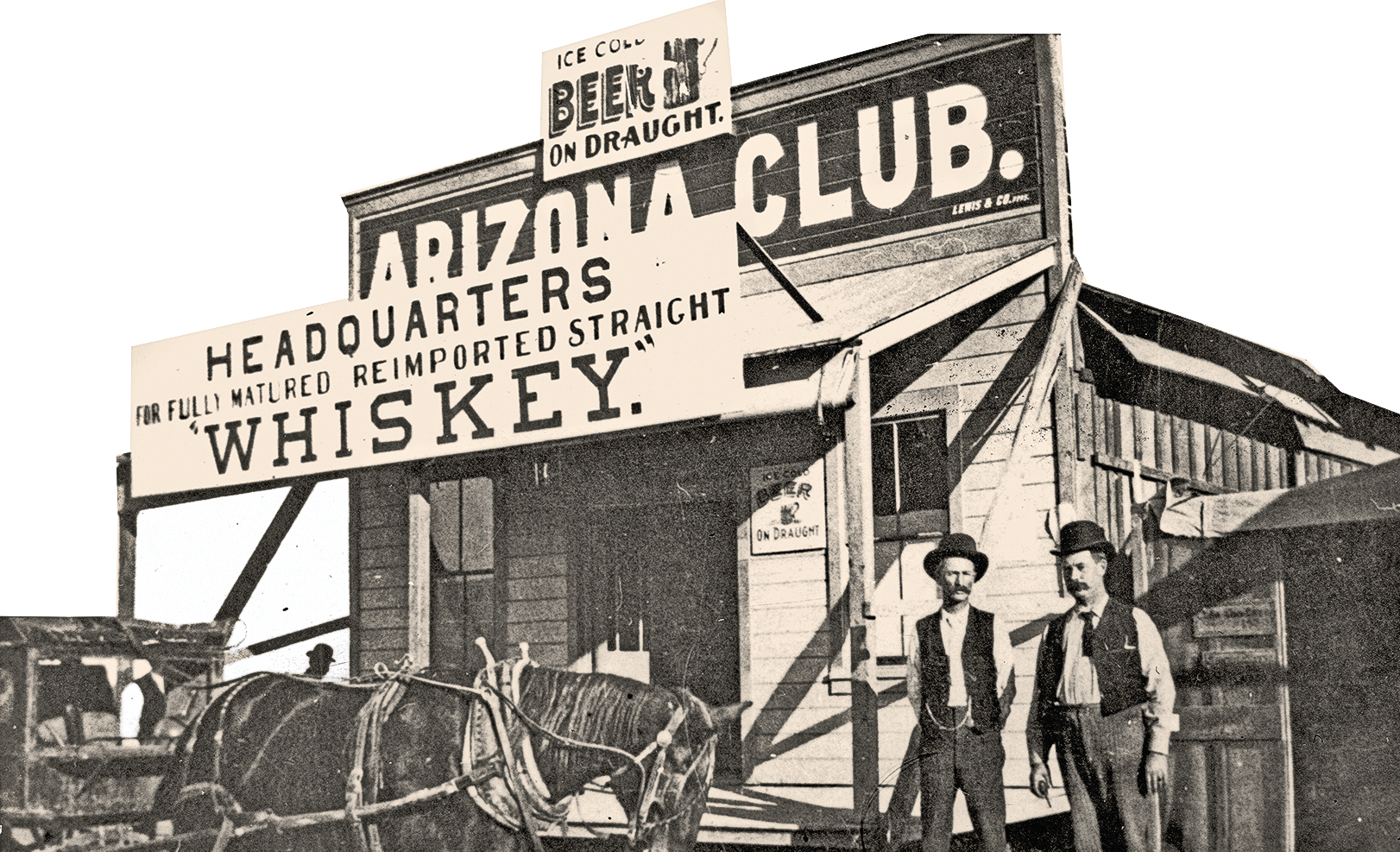

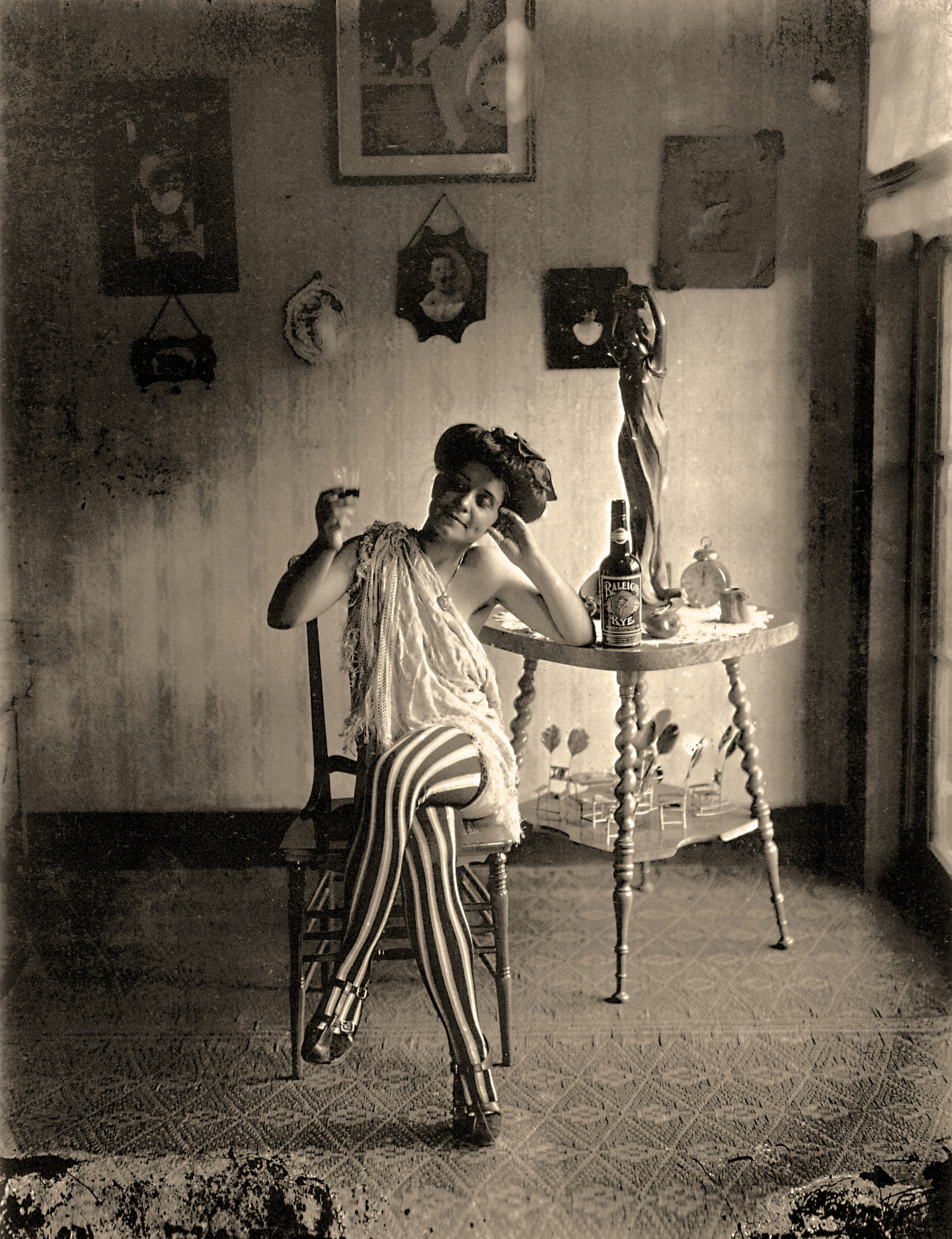

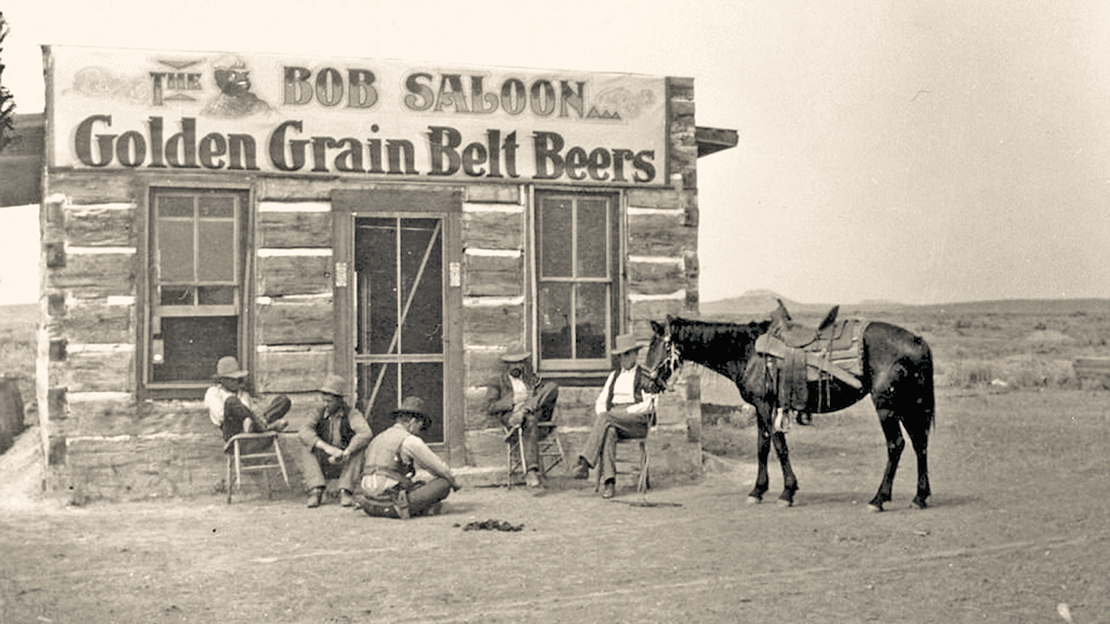

Boom and Bust

Businesses all across the West boomed with whiskey, but none more than the saloons, dance halls and brothels. Other than the distillers themselves, the men and women involved with these businesses undoubtedly had the biggest connection to, and profited the most from, whiskey’s influence. They were the epicenter of most towns, the place where men gathered to get their news, talk politics and unwind, further establishing whiskey’s influence in the shaping of the West. In money towns like Tombstone, Arizona, Virginia City, Nevada, or Dodge City, Kansas, popular whiskey drinks of the day included Whiskey Cocktails, Whiskey Slings, Whiskey Punches, Rock and Rye and Stone Fences. Only in rural or poorer towns would saloon owners serve their customers a simple shot of rotgut or cheap whiskey in dimly lit, ramshackle watering holes.

– Courtesy BBCW, PN.89.112.21262.10, Cody, Wyoming –

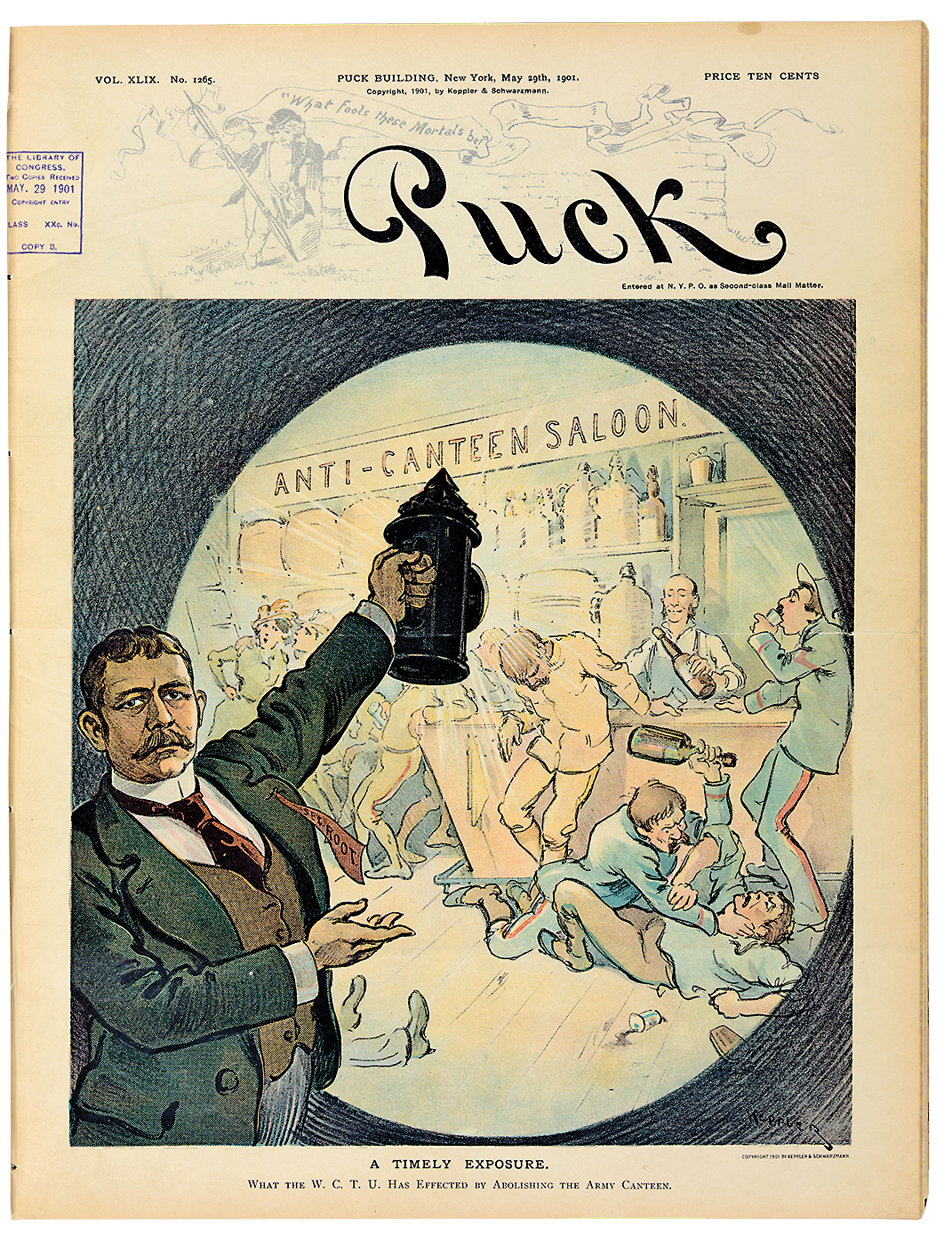

Whiskey had become the popular tipple of the American West, but its rise was about to fall. As the turn-of-the-century neared, so did the push for regulation and temperance. The Bottled in Bond Act was enacted in 1897 because, until then, the government did not regulate what was put in whiskey bottles and sold to the public. The act was a significant regulatory reform and ensured that 100 percent of the liquid sold as single-malt whiskey was distilled in the same distilling season, by a single distiller, and that the spirit had been aged for a minimum of four years in a federally bonded warehouse. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union had been created in the 1870s and was pushing for Prohibition. State prohibition laws, and eventually national Prohibition, were passed and brought another chapter of scrutiny, economics and opportunities to control markets. When the repeal of Prohibition allowed whiskey back on the market, it was regulated and mass-produced, and the love affair between the American West and whiskey was all but over.

Whiskey in the West Today

Today, that’s all changed and America is back in love with the golden elixir. The whiskey industry is experiencing a renaissance of distillers and their spirits—and a significant number of distillers are now located in the American West. Single barrel bourbons, single malt Scotches, whiskey festivals with educational whiskey seminars, whiskey magazines and much-improved and expanded distillery tours are paving the way for the small-batch distiller and the American brown spirit’s revival. Small-batch distillers are being propelled by a combination of modern trends in consumer products, including celebrating local heritage and interest in unique artisanal products. The emphasis on buying quality local products from people who share details about their origins also plays a role. Novel product innovations have also allowed the smaller distilleries to gain recognition.

– True West Archives –

Some of today’s artisan distillers are experimenting with blue corn, oats, quinoa, amaranth and other exotic ingredients. Balcones Distilling in Waco, Texas, created its Baby Blue whiskey from roasted heirloom blue corn, and its Brimstone whiskey is smoked with sunbaked Texas scrub oak. While some distillers are using exotic ingredients that the pioneers didn’t even know existed, others are using technological distilling methods. It’s quite possible that Western frontier whiskey-makers may have experimented with the maturation process by adding smoked woodchips or tree bark to the barrel to speed the flavor process, as is being done today at Boothill Distillery in Dodge City, Kansas. It uses 75 percent corn, 25 percent wheat whiskey mash and it is aged in 30-gallon barrels for a month with added oak spirals for extra infusion. The modern trend in Western whiskey-making is not to return to quantity and lower cost, but to emphasize quality and innovation.

– Courtesy Deadwood Inc., Adams Museum –

Sherry Monahan has been writing about food and beverage on the frontier since 1998. She was curious about why whiskey, and not rum or vodka, is associated with the West. That led her to write a book titled Golden Elixir of the West, which explores that and a whole lot more about whiskey in the West.