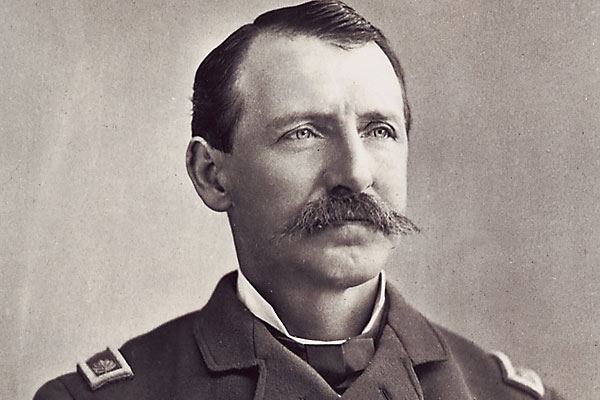

In February 1, 1896, Col. Albert Jennings Fountain and his eight-year-old son Henry were on the last leg of the 150-mile trip from Lincoln, New Mexico, to their home in Mesilla.

They’d been on the rough road for nearly three days, braving cold winter winds and temperatures. They passed the White Sands area as daylight faded; they were about to become the subjects of a great Old West mystery.

What happened to the colonel and his boy? It’s a question that’s been posed for more than 110 years. A few books included the odd chapter to the case, but it’s only now that someone has written a full-length treatment of the Fountain disappearance—first-time author Corey Recko, in his book Murder on the White Sands. Recko discusses some previously unpublished writings of men investigating the case.

The Threat of Death

That somebody had it in for Albert Fountain was no surprise.

He’d always been a “love him or hate him” kind of guy—an attorney, politician and public figure who spoke his mind. He made some powerful enemies, so threats against his life were all too common. His reputation also took a hit when he served as defense counsel at Billy the Kid’s 1881 murder trial.

In Lincoln in January 1896, the colonel obtained grand jury indictments against rancher Oliver Lee, his pal Bill McNew and 21 others on charges of cattle rustling. A dangerous man, Lee had at least one killing to his credit; He and McNew also served as Dona Ana County deputy marshals. The deputies were close associates of Judge Albert Fall, a leader of New Mexico’s Democrats—and a bitter enemy of Albert Fountain. The indictments came down; Fountain took much of the evidence with him on the return to Mesilla.

He knew the trip was dangerous. On the last day of the grand jury, somebody handed him a note stating, “If you drop this we will be your friends. If you go on with it you will never reach home alive.”

His son Henry had traveled with him, after Albert’s wife insisted nobody would kill the man in front of a little boy. And they certainly wouldn’t hurt the kid.

As father and son made the lonely journey home, the elder Fountain saw a number of riders watching them from a distance. They never got close enough to identify. Others who passed the Fountains on the road saw the men too and urged the colonel to be careful. But he wanted to get home, and he didn’t want to show any fear. The trip continued.

The Investigation

When they failed to arrive home on February 2, folks went looking for them. Searchers found their empty wagon, and some of Henry’s clothing. A large bloodstain covered the ground near where the wagon had left the road. Not far away, shell casings proved at least one man had knelt behind some brush and fired a rifle. Something bad had taken place—but just what?

A top Pinkerton agent was hired to look into the case. Legendary lawman Pat Garrett was also called in. Tracks from the crime scene—most were convinced Albert and Henry had been murdered—led to Oliver Lee’s ranch. Yet the evidence was circumstantial, and nobody had found any bodies. Investigators also faced numerous roadblocks thrown up by Lee and his men, and their friend Albert Fall.

A grand jury handed down indictments against Lee, McNew and Texas hardcase James Gilliland later that year, but the accused made themselves scarce. Not until three years after the murders, in May 1890, were Lee and Gilliland put on trial. (McNew was never brought to trial.) And they were charged only in the murder of Henry Fountain. The defense lawyer Albert Fall was one of the best, ripping into witnesses and blowing big holes in the prosecution’s case. The jury deliberated just eight minutes before finding the defendants not guilty. Nobody was ever tried for the murder of Albert Jennings Fountain.

An Admission of Guilt?

Fast forward to 1937. An elderly Gilliland spills his guts about the case, admitting that he, Lee and McNew had killed the Fountains—and he showed one man the site where the two were buried. Yet when authorities dug through the area, they found no remains. For their parts, Lee and McNew (and their descendants) always denied any involvement in the murders—so did Albert Fall, who some suspected of ordering the hits.

In his book, Corey Recko reports that Lee, McNew and Gilliland probably did commit the crimes, and Fall was likely not directly involved. But even Recko admits that many questions remain to be answered about this great Old West mystery.