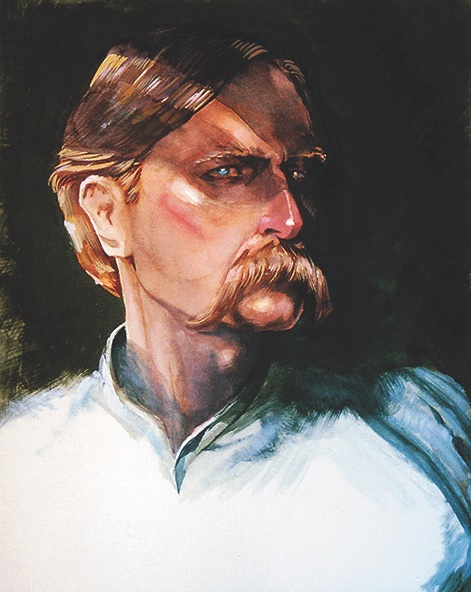

Historians and writers share their perspectives on the West’s most famous lawman.

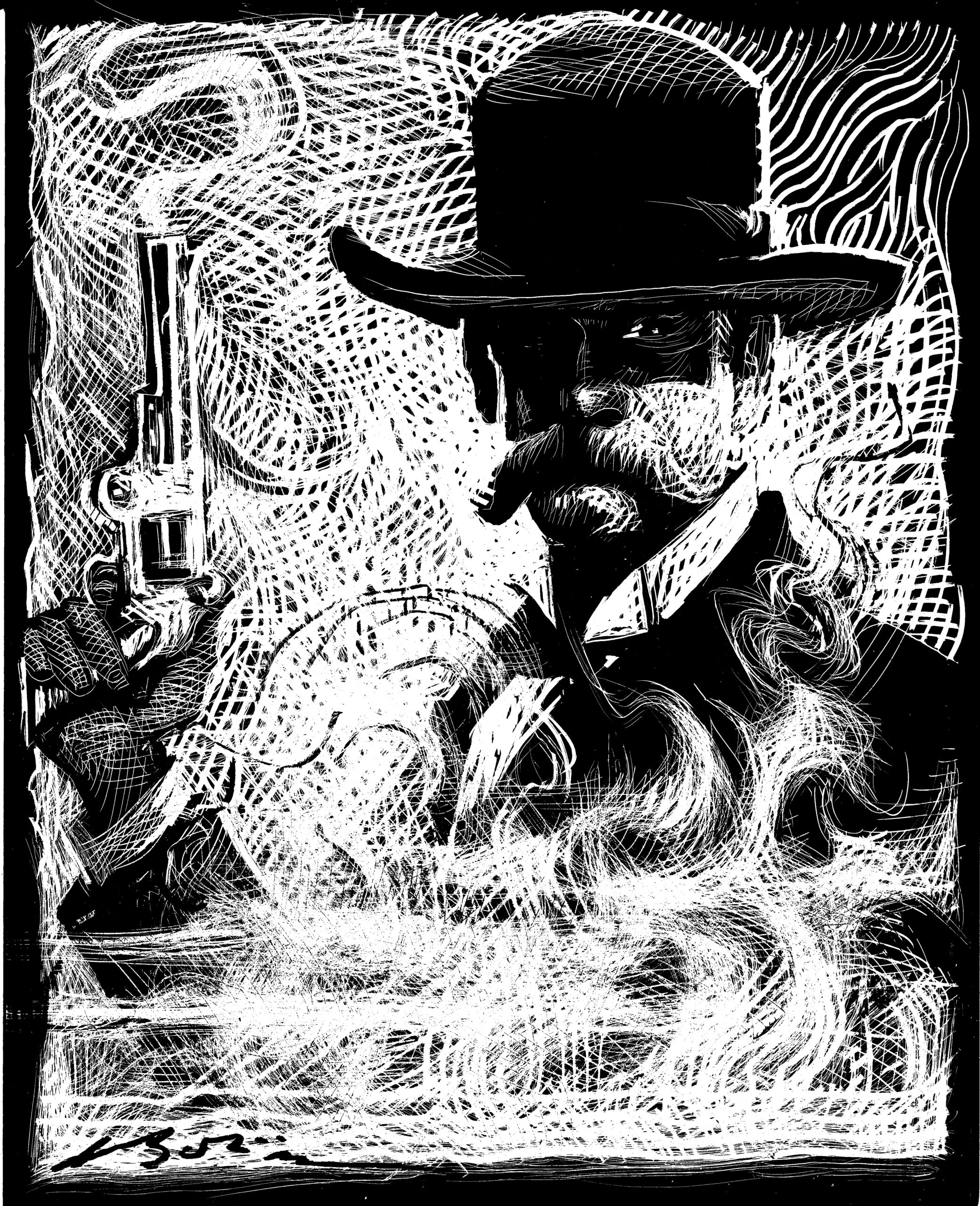

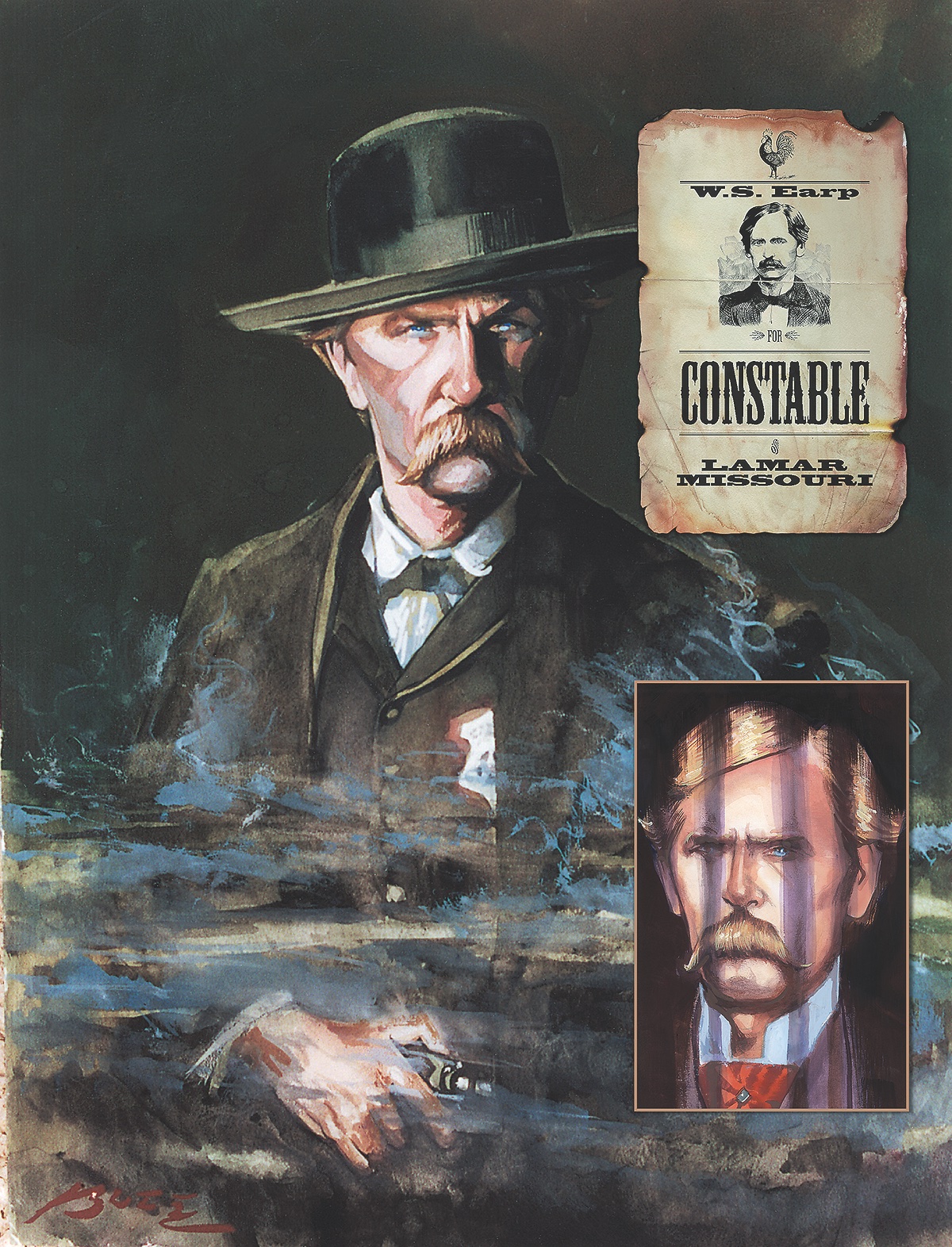

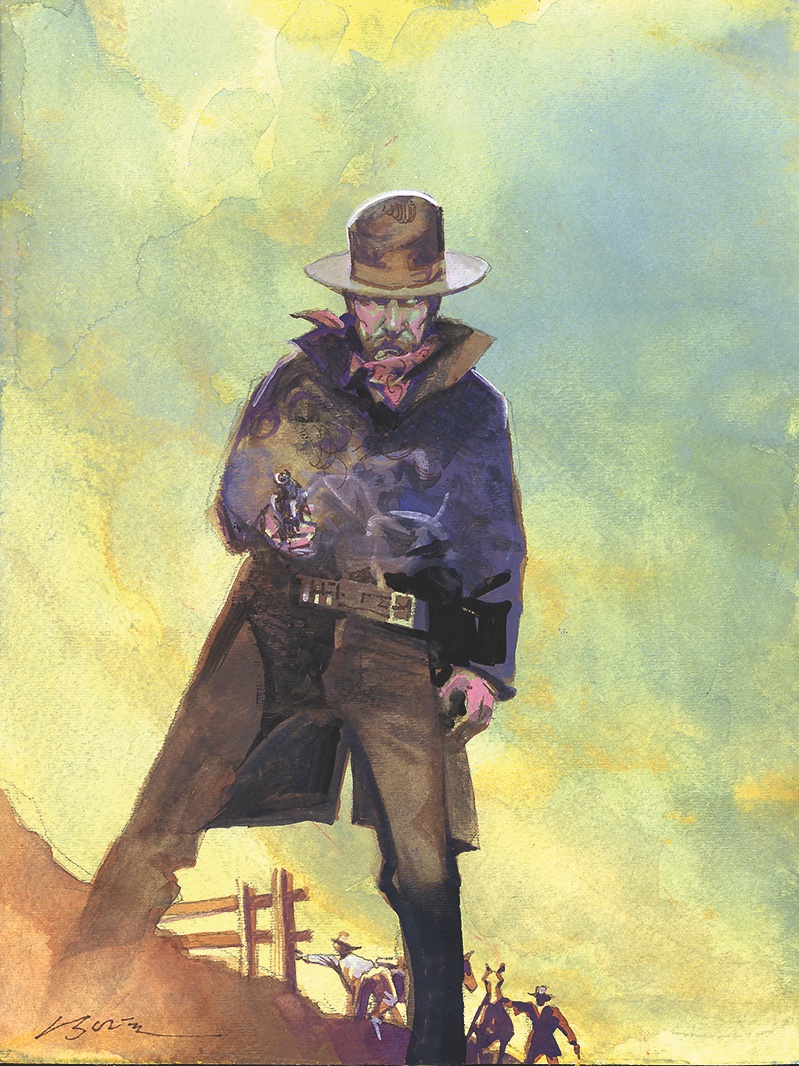

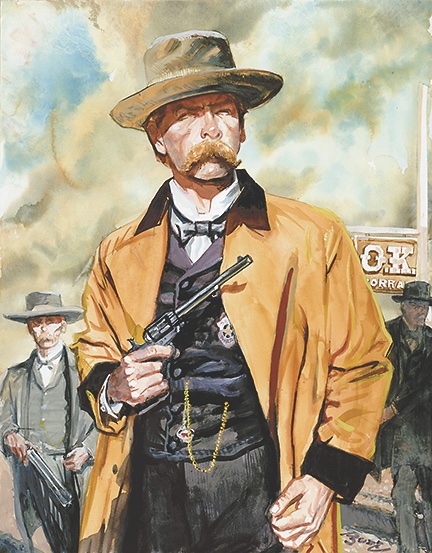

In honor of the 140th anniversary of the gunfight near the O.K. Corral between the Earps and the Cowboys in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, on October 26, 1881, we have asked fellow Earp historians, writers, novelists, artists and friends to weigh in on the question “Is Wyatt Earp still the hero?” We have given True West’s historian Paul Andrew Hutton the first word on the frontier marshal. And rightfully so, Wyatt Earp historian, artist and executive editor of True West Bob Boze Bell will have the last.

A HERO’S JOURNEY

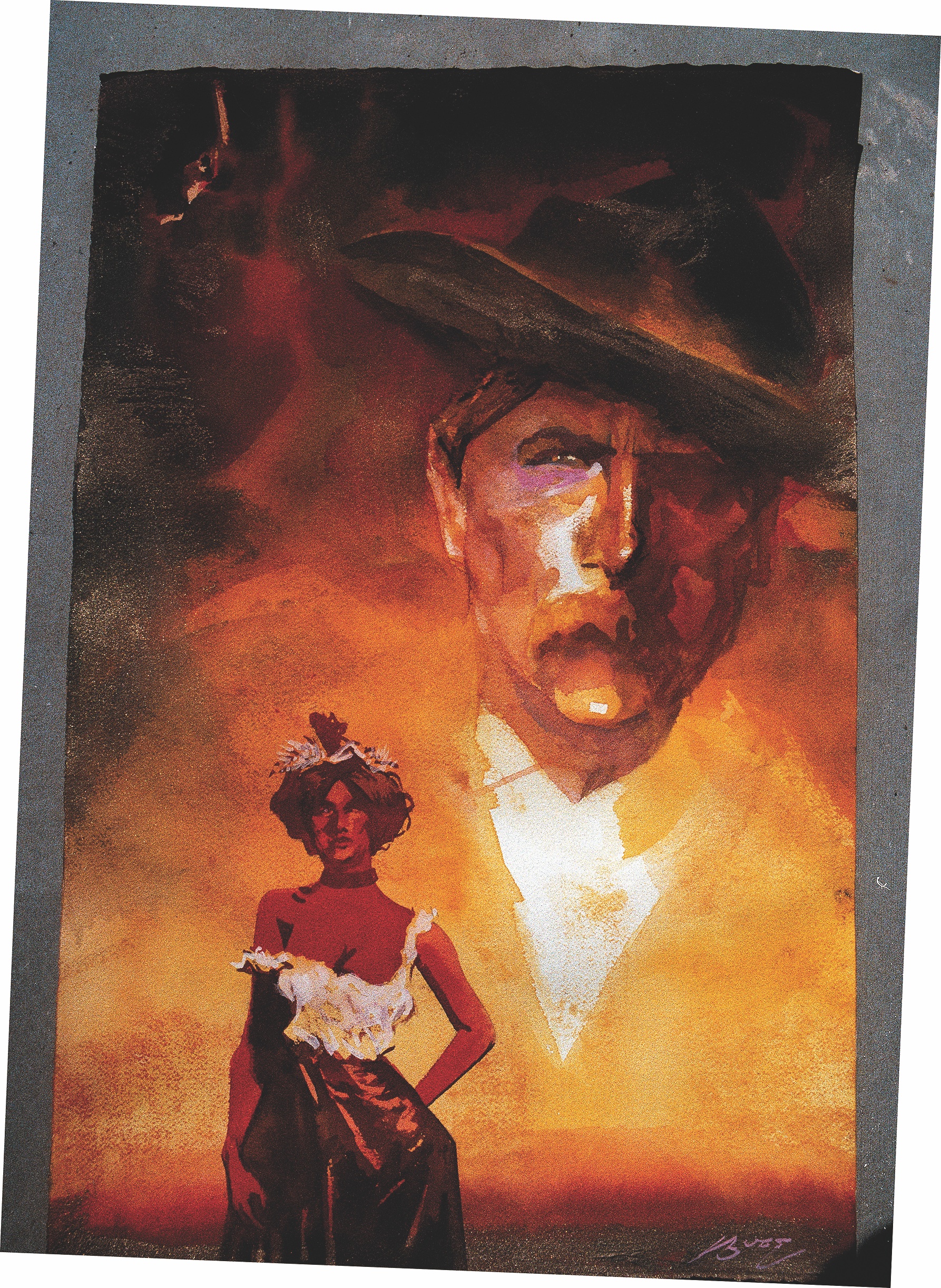

One hundred and forty years after that perfectly named gunfight that made him famous, and 90 years after the publication of Stuart Lake’s biography that ensured him immortality, Wyatt Earp remains firmly fixed in the pantheon of America’s heroes. The tireless work of debunkers in history, fiction and film has failed to tarnish the shiny star of the town-taming marshal who finally had to step outside the law to deliver true American gunpowder justice. The debunkers’ work has had scant impact on public perceptions (and, of course, the sometimes sordid details of his life are far too deep in the weeds for most people to care about anyway). The latest Earpiana—most notably the books by Casey Tefertiller and John Boessenecker and the films Wyatt Earp and Tombstone starring Kevin Costner and Kurt Russell—have all cast Earp in a heroic mold. Earp’s supreme moment of truth at the O.K. Corral has become part of the American lexicon, while also serving as the prototype for every Western showdown written about or filmed since October 26, 1881.

Wyatt Earp was a late bloomer as a hero. While he was certainly well known on the frontier, especially in boomtowns, on the gambling circuit and as an all-around “sporting man” of some distinction, he was never remotely as famous as Davy Crockett, Kit Carson, Wild Bill Hickok, Jesse James or Buffalo Bill Cody. The O.K. Corral fight was reported in the national press but usually in a negative light as an example of uncivilized lawlessness in the West. Bat Masterson and Pat Garrett were far better known as frontier lawmen in their own time than Earp.

The seed of Earp’s fame was planted, fertilized and carefully nurtured by Stuart Lake, a gifted writer who had once been a press agent for Theodore Roosevelt. Lake crafted a remarkable American epic in Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal published by Houghton Mifflin in 1931. This was perfect timing, for the public was eager for tales of the American frontier just as the generation that had “won the West” was dying off. Western histories by Walter Noble Burns, Emerson Hough, Frederick Bechdolt and William McLeod Raine had all recently done well, and Lake also enjoyed considerable success as his Earp biography became a bestseller and was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post. Lake’s Earp was central to the frontier story. “The Old West cannot be understood unless Wyatt Earp is understood,” he wrote. “More than any other man of record in his time, possibly, he represented the exact combination of breeding and human experience which laid the foundations of Western empire.”

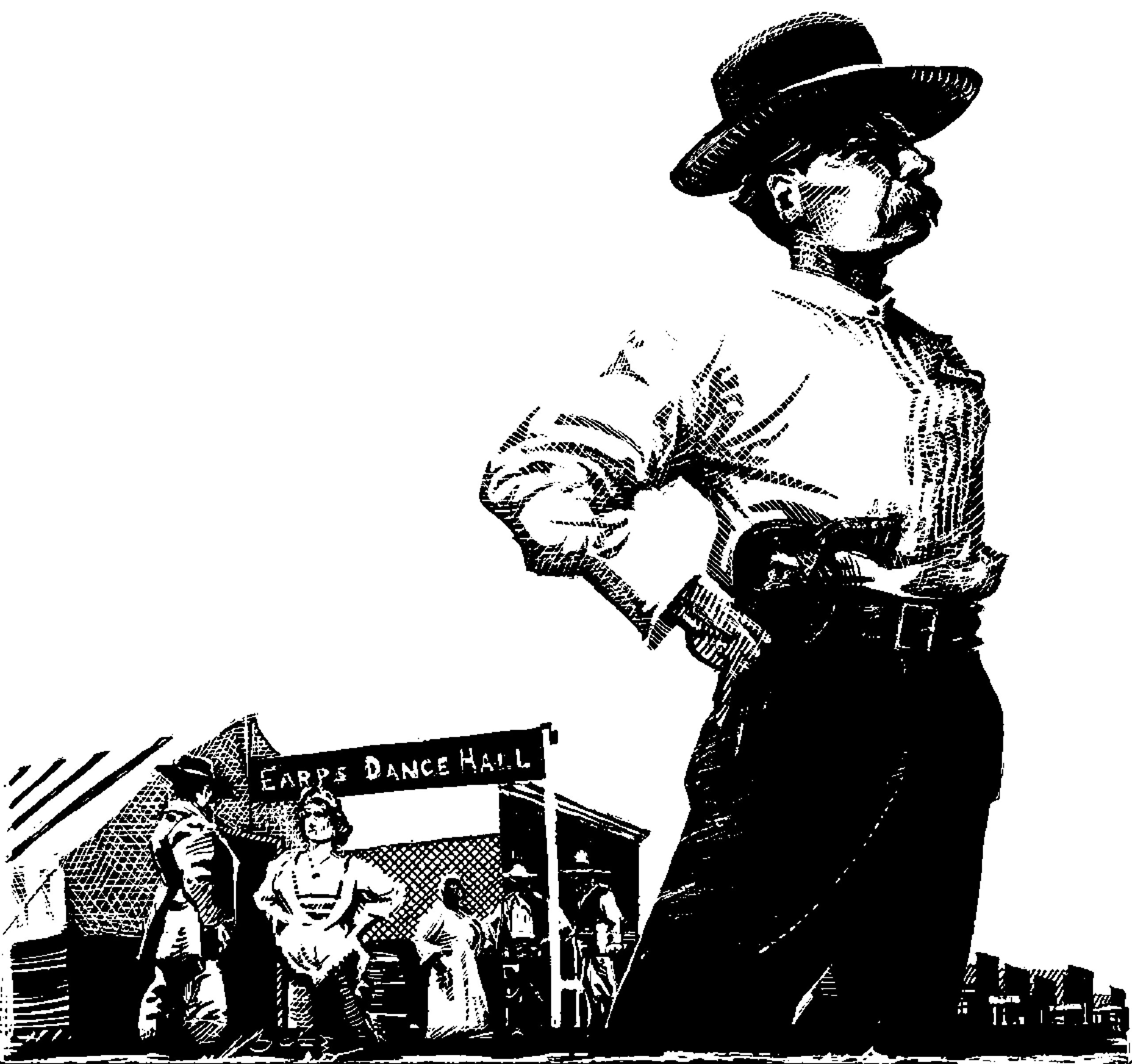

Thanks to Lake, Earp, the itinerant gambler and sometime lawman who lived rather precariously on the dark underbelly of frontier boomtown life emerged as the towering legend of an incorruptible marshal who tamed the toughest towns in the West. Lake’s book was optioned by Fox studio for $7,500 and was filmed four times (Frontier Marshal with George O’Brien in 1934, Frontier Marshal with Randolph Scott in 1939, My Darling Clementine with Henry Fonda in 1946 and Powder River with Rory Calhoun in 1953). Over 40 films have been based on Earp’s career, and Hollywood has played the critical role in creating and sustaining his glossy legend. Lake’s book also provided the inspiration for the ABC television series starring Hugh O’Brian that premiered in 1955. The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp ran for six seasons, and its success helped initiate a decade-long period during which Westerns dominated the small screen.

In a snide 1959 article on the Western TV boom, Time magazine noted that the real Earp was “a hardheaded businessman, less interested in law and order than he was in a fast buck.” The success of the show Time attributed less to history than to O’Brian’s muscles and square jaw. “Actor O’Brian (real name Hugh Krampe) looks like an Oklahoma Olivier. In his flowered vest, ruffled shirt, string tie and sideburns, and with two 16-inch Buntline Specials strapped to his thighs, he really cuts the mustard with the teenage cow bunnies.”*

This television white knight was ripe for debunking, and Ed Bartholomew and Frank Waters promptly obliged. Their Earp, a con artist and ruthless killer who hid behind a badge, was copied by a string of lesser talented researchers and writers. Waters, a distinguished Western writer, was a caustic forerunner of the current “woke” generation. His attack on Earp was also meant to deconstruct the frontier myth of American progress and exceptionalism that he blamed for many of the planet’s problems. The source of all these ills, according to Waters, was “America’s only true morality play—the Cowboy and Indians movie thriller…the basis of our tragic national psychosis—a fixation against all dark-skinned races, beginning with the Red, which was killed off, and carrying through to the Black, which was enslaved, the Brown legally discriminated against, and the Yellow excluded by legislation.” Waters felt that if only he could dismantle the heroic Earp legend, he could begin to destroy the whole frontier narrative. Lake’s Earp was central to his task: “This veritable Wild West textbook…[the source] of other books, pulp-paper yarns, movie thrillers galore, radio serials, a national TV series, Wyatt Earp hats, vests, toy pistols, tin badges—a fictitious legend of preposterous proportions.” In two books, The Colorado in 1946 and The Earp Brothers of Tombstone in 1960, Waters attempted to bring down the Earp legend and the American frontier story that it was such an integral part of.

Waters failed in his own time to destroy the heroic story of the frontier movement, but his writing foreshadowed the so-called “New Western History” that would come to dominate college classrooms a generation later. That dark vision of the American past in turn spread to public schools across the nation. The result is the bitter debate over our shared history that dominates public discourse today. With the gentlemen on Mount Rushmore targeted for cancellation, it may be that Wyatt Earp is low enough on the totem pole of American heroes to escape attention—but do not count on it. If he does raise the ire of the “woke mob,” it will not be in response to the reality of his life, but rather to the frothy legend so lovingly constructed by Stuart Lake and his posse of fellow travelers in Hollywood.

Heroes are but a reflection of the beliefs and aspirations of those who embrace them. People identify with heroes, and as society evolves and changes, old heroes are often replaced by new figures. But some characters are so great that they have resisted change. These heroic figures—from the time of Homer’s tales of Greek and Trojan warriors to the last stand of the Spartans at Thermopylae, from the legends of King Arthur and El Cid to the battles between Richard the Lion Heart and Saladin, to the forests, mountains and plains of the New World, where the names of Boone, Crockett, Carson and Cody would become legendary alongside those of their foes Tecumseh, Red Eagle, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Geronimo—have all shaped national identity. Our heroes define us. If these hero tales (no matter the truth of them) are rejected, it indeed makes a powerful statement and can erode any sense of national unity.

Is Wyatt Earp still a hero? Time will tell.

*Actually, the Time author was incorrect: O’Brian’s Earp was armed with one 16-inch Buntline Special and one normal length Colt revolver.

—Paul Andrew Hutton

Wyatt a hero? I can hardly hear you; Josephine is hollering at me; William Shakespeare is yelling something about tragic flaws…but the ghost of Lincoln Ellsworth is whispering YES.

—Ann Kirschner

The real Wyatt was certainly a man of physical courage, as were many people of the Western frontier. But it’s the other half of the definition that’s the harder test, the part about being a person of high moral principles. And the answer is, sadly, no, unless you consider things like frequenting bordellos, gambling and killing your enemies to be high moral behavior. Neither in his time nor in ours would those things be considered principled activities. So, although his real adventures make for a good story, they do not reveal true heroism, in the total sense of the word. It took novels and Hollywood to make a hero out of Wyatt Earp.

—Victoria Wilcox

“I think he was a pimp, a thief and a killer.” -Michael Biehn

I would say Wyatt Earp was a brave man who did what he thought he had to do. He was certainly flawed and did many questionable things in his life, such as pimping, horse theft, gambling and bunco; so not heroic, but certainly brave and someone I would want by my side in a fight.

—Peter Brand

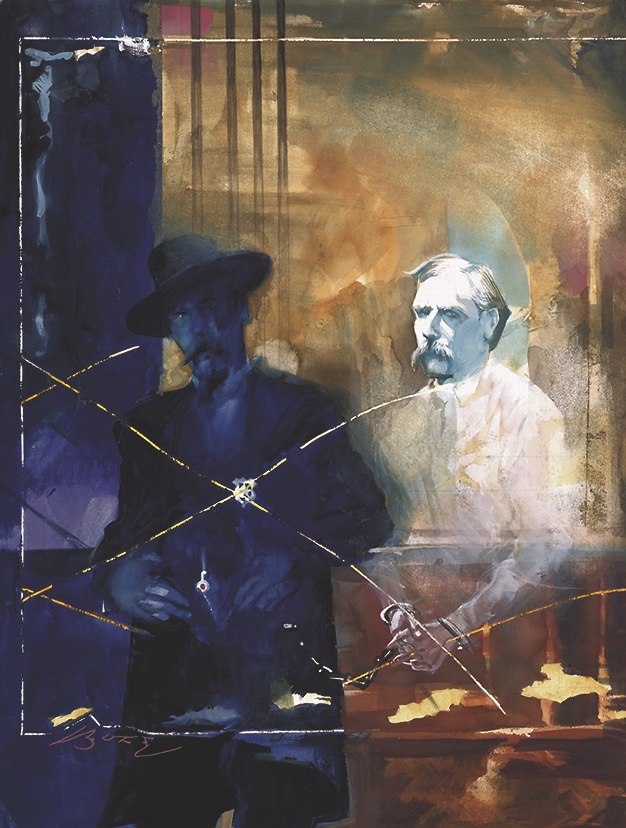

I have long felt the film Ride the High Country is a film about the battle waged for Wyatt Earp’s soul. Joel McCrea had portrayed Wyatt Earp in Wichita (1955) and Randolph Scott had portrayed Earp in Frontier Marshal (1939). Two years before Sam Peckinpah’s second film was released, Frank Waters’ The Earp Brothers of Tombstone was published. So, at the time Ride the High Country was in production, there were two decidedly different takes on Wyatt in print. Stuart Lake presented “Wyatt the Good,” while Frank Waters presented “Wyatt the Bad.” In the Peckinpah film, McCrea plays a lawman of high principle, “Wyatt the Good.” Scott plays a former lawman who has taken to exaggerating his exploits and who is not above breaking the law to increase his wealth, “Wyatt the Bad.” There are hints in the film that Wyatt is being dealt with in the film’s story. First, the Earps are mentioned by McCrea, seeing a banner that claims Scott had cleaned up Dodge City, McCrea says, “I didn’t know you ran with the Earps.” Then, the final gunfight is obviously based on the O.K. Corral shooting. When Warren Oats yells out, “Start the ball, Old Man!” to start the shooting, he is echoing Ike Clanton, who on the day of the O.K. Corral shooting, said, “The ball will open when Holliday and the Earps appear on the street.” So, while the film tells the story of the conflicts in Wyatt Earp’s soul, by extension, it is also covering the conflicts in the soul of America, a nation conflicted by noble ideals on the one hand, and unprincipled opportunism on the other hand.

—Jeff Morey

Humans need heroes. All great heroes are flawed, both real and mythical: Samson, Hercules, King Arthur, Frodo, Mickey Mantle, The Duke, Patton, Reagan and Wyatt Earp. A hero is just someone who does the right and necessary thing at the right time—even if it’s not always for the right reason. Yes, Wyatt is still a hero.

—Lydia O’Rafter

Wyatt Earp, to me, has never been either a hero or a villain, but a complex individual with some admirable qualities and flaws; pretty much like any other gun-toting historical figure on the frontier. The contradictions that partly come out of the “legend” portrayals and differing perspectives are very interesting to me. Most Earp aficionados have no objections to his going on a rampage during his “vendetta ride” and pitilessly gunning down men in vengeance. I have no problems with it either, but why has it always been seen as okay for Earp to do that, but Bonney and the Regulators are routinely condemned for their own vendetta ride in the spring of 1878 when they gunned down Morton, Baker, Brady and Hindman to avenge a brutal murder? I fail to see the distinction between the two courses of action.

What, because Brady wore a badge? Pah-lease, so did John Selman, for chrissake.

—James B. Mills

So, is Wyatt Earp a hero? In this writer’s opinion, he meets the criteria, by virtue of his actions and what his story did for one of my favorite places in the world: the town too tough to die, Tombstone.”

—Randie Lee O’Neal

So he was friendly with whores. So was Jesus. So Earp clobbered people with pistols. So did Hunter S. Thompson. So he was a Republican. So was John McCain. Heck…your question takes me by surprise…as if it had been written by an associate professor of Woke Studies.

—Red Shuttleworth

To me a hero is someone who saves lives not someone who takes them. Jesus hung out with prostitutes to save them, not because he was their pimp. Wyatt was doing a job, that doesn’t make him a hero.

—Larry Willis

During the last three decades, an enormous amount of material has been dug out to better illuminate Wyatt Earp and the Tombstone saga. Some may seem to tarnish Earp; some may seem to enhance his reputation. Together it shows that Wyatt Earp was never the stainless hero created by legend-making writers and filmmakers. Very few historical figures can live up to their legends.

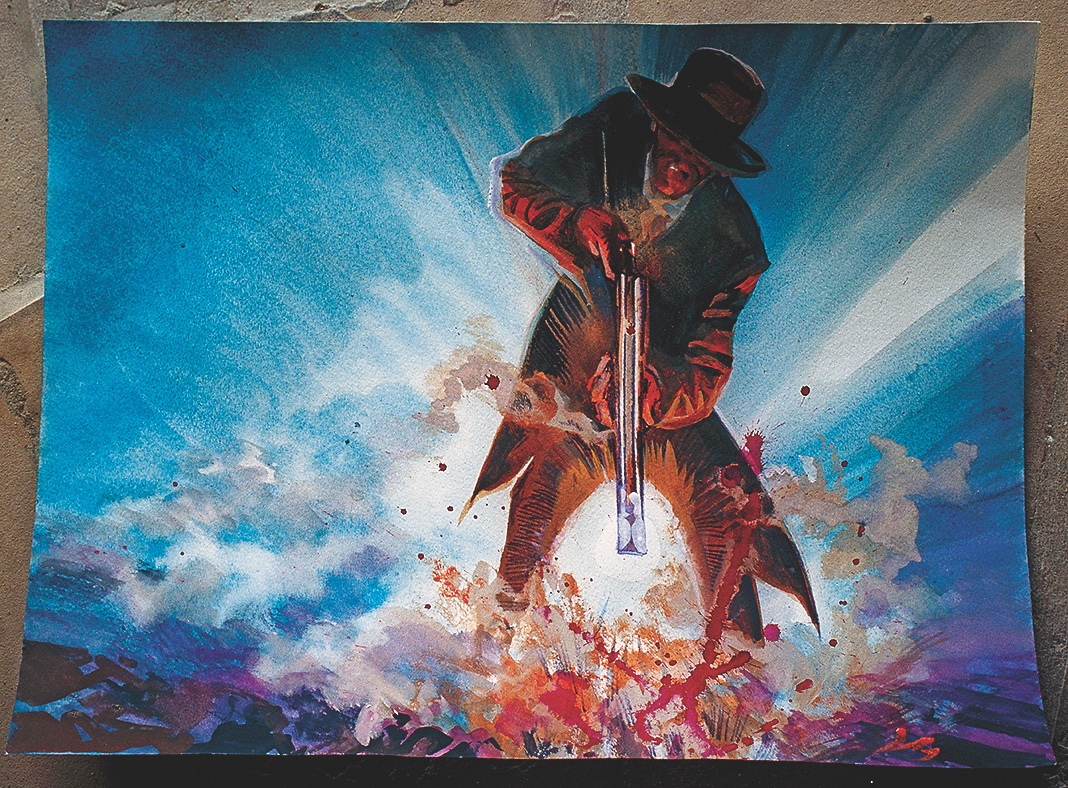

With Earp, the more we learn, the more interesting he becomes. He certainly had his personal flaws, but when the time came to stand tall, tall he stood. The Tombstone story is really about what happens when outlawry grows out of control, and how a community responds. It resonates today as it did 14 decades ago.

When that challenge came to Wyatt Earp, he responded with remarkable courage. If that is the test of heroism, then he passed with nobility.

—Casey Tefertiller

Wyatt Earp has long been known to students of the Old West as an itinerant frontier gambler whose entire law enforcement career lasted only seven years. Then, during the past two decades, a great deal of previously unknown information about Wyatt has surfaced. For many historians and Western buffs, he has since evolved from the Lion of Tombstone to the Pimp of Peoria. Nonetheless, of all the adventures and misadventures in Earp’s life, his epic battle against the Cowboys in Arizona Territory made him a hero, then and now. In 1881-1882 Wyatt, his brothers and a handful of loyal friends took on and defeated the biggest outlaw gang of the Old West. It was the highlight of his life, and remains one of the most remarkable incidents in the history of American law enforcement.

—John Boessenecker

Directly after the shocking assassination of President James Garfield, Tombstone’s city government enacted zero-tolerance gun control ordinances. On October 26, 1881, City Marshal Virgil Earp was ordered by Mayor John Clum to disarm men seen carrying weapons inside city limits. Those men were at the O.K. Corral because they were leaving town and they had the right to take their guns with them, but the confrontation accelerated within moments. The officers were later exonerated using legal logic that protects police in officer-involved shootings to this day: they reacted quickly to a perceived threat in a pressured situation.

Where’s the heroism? Wyatt never claimed it. He was dogged for the rest of his long life by the worst 30 seconds of it. After he died, his widow took control of his posthumous reputation, insisting that Stuart Lake write the hagiography that became a TV show: The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.

I can still sing the theme song, but the West was not lawless, and no man is flawless. I look for my heroes elsewhere.

—Mary Doria Russell

Wyatt Earp: Frontier lawman, gambler, outlaw, Western legend. An icon whose reputation, justified or not, has been created and enhanced through literature, films and television. Justified by some, vilified by others. Loyal, vengeful, complicated, egotistical, arrogant, passionate, moody, stoic. Before you develop your opinion, however, forget the film and television. They are just entertainment, and, in most cases, highly fictionalized. Read the books…plural. Some well researched, others not so. Then make up your mind. All Earp wanted to do in life, as with many, was to take advantage of the situation and do what he thought was right.

—John Farkis

I’m not sure if Wyatt ever deserved the “hero” designation. The Earps as a family were shameless opportunists who never took a stand without a buck being attached to it. The celebrated gunfight was the culmination of a petty political squabble that had little impact on the outcome of American history—like so many legends, a local affair blown all-to-hell out of proportion. Unimportant and irrelevant, especially at a time when a new generation of learners fail to find themselves in the prevailing narrative.

—Kirk Ellis

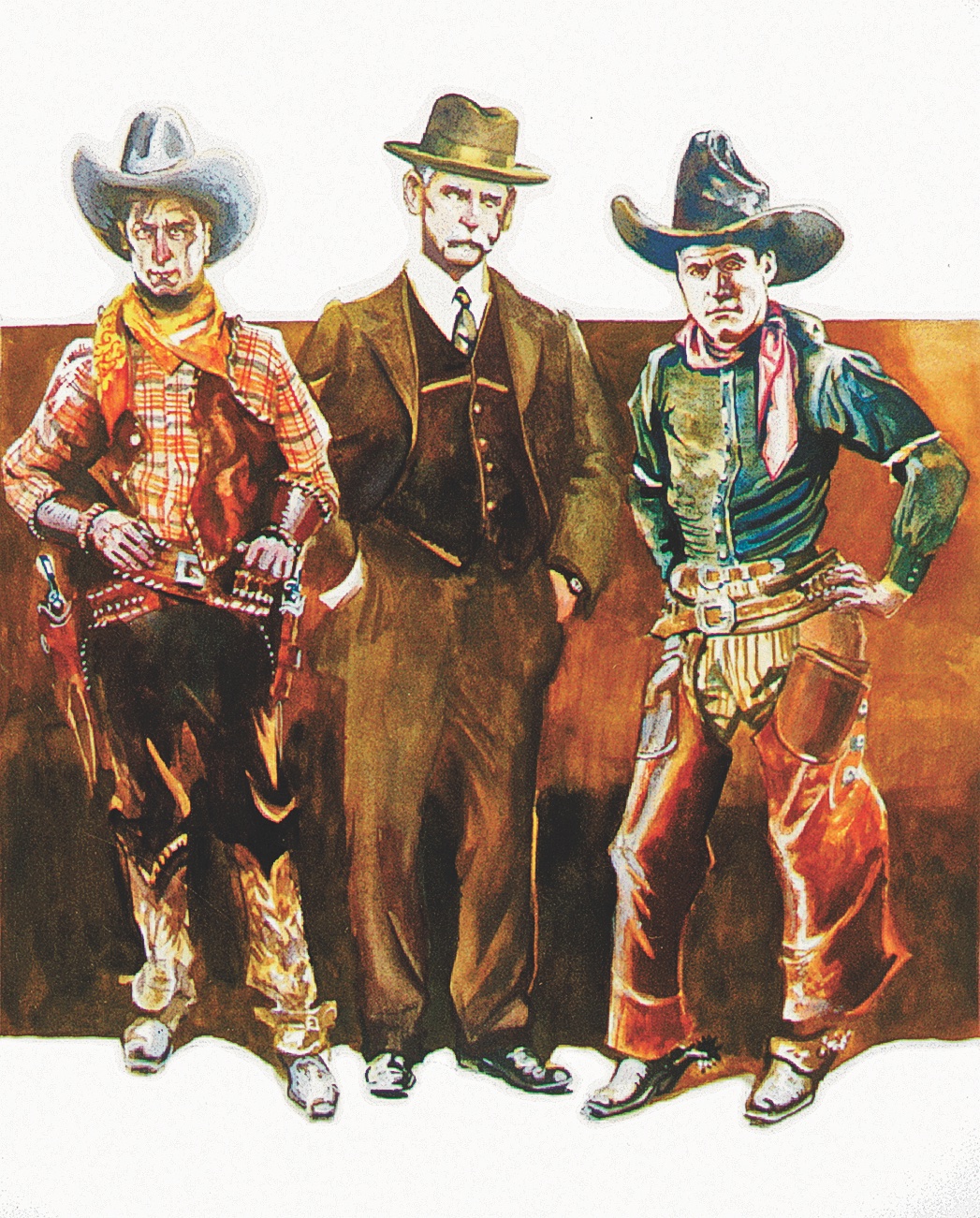

Left to right: James, Warren, Wyatt, Nicolas, Virgil and Morgan. Two died from gunshot wounds, four were wounded in gun battles and the father was kicked by a mule. Only one came through it all without a scratch—Wyatt Earp.

I don’t think of Wyatt Earp as a hero. The very premise of a “good guys-bad guys” approach to history distorts the humanity of the individuals so labelled and the issues that they confronted. Honestly, I can’t even call him a good man, given his checkered career and flaws of character. But he was respected and even admired by good men who saw in him qualities they envied. He lived for 81 years, and the violent moment for which he is best remembered lasted less than 30 seconds. Add the few months of the Vendetta and the deaths that came with it, and he was still a better man than those he killed.

—Gary L. Roberts

“Wyatt Earp matters because of what he means, not for who he really was.” -Thom Ross

Wyatt Earp will always be my hero. Sure, he wasn’t a saint, but don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

—Paul Hoylen

I don’t look at Wyatt Earp as either a hero or a villain. Projecting our own mores and values on people of another time leads to false perceptions and a warped view of history. He was a man of his time, doing what seemed right by his own lights.

—Doc McCandless

It’s easy to get bogged down in the weeds with someone like Wyatt Earp. Is he a hero? Sure. A villain? Probably. He embodies everything we Americans like about ourselves, our history and our so-called “great men.” And everything we don’t like, too. There’s a little dirt on most American heroes, and Wyatt Earp is no exception.

—Samuel K. Dolan

Although Wyatt Earp demonstrated toughness and bravery, he was really only out for himself and his family.

—Greg Scott

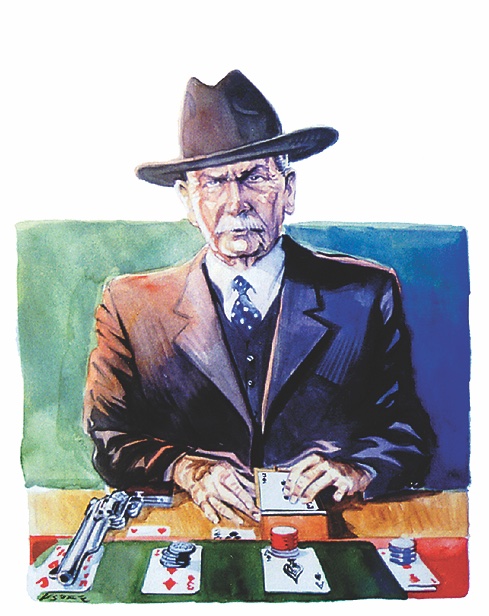

It’s doubtful that any American has had more of his legend turned into “fact” than Wyatt Earp, who had a brief career as a frontier peace officer and scarcely wore a badge over the last 48 years of his life. Before and after ”lawing,” as it was called in the 19th century, Earp was a teamster, boxing referee, prospector, buffalo hunter, racehorse owner, croupier, stagecoach guard, bouncer, saloon keeper, bodyguard, Hollywood movie advisor and, for a while before he became a noted lawman in Kansas, a pimp. He’s been portrayed by more actors than any American president—Walter Huston, Henry Fonda, Burt Lancaster, Hugh O’Brian, James Stewart, James Garner, Kurt Russell and Kevin Costner, to name just a few. But the only years Hollywood has taken notice of are those spent in the cow towns of Wichita and Dodge City, Kansas, and the silver mining camp, Tombstone, Arizona. What happened over that brief span has engendered enough books to fill a small library.

—Allen Barra

Having grown up on such TV staples as The Adventures of Rin-Rin-Tin and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, when my family planned to relocate to Arizona, I couldn’t wait. Not long after arriving, we made the pilgrimage to Tombstone. Strapping on my pair of cap guns, I expected a showdown there with Hugh O’Brian. Alas, I never faced his “Buntline Special.”

More than 65 years have passed. Since then, most of us have a far different perspective on the marshal of the “Town Too Tough To Die.” Stuart Lake’s fanciful biography, early television and movies have been replaced by scores of “factual” articles, documentaries and tomes of varied size and quality toppling the Earps from their pedestals. As a historian, I appreciate such scholarly efforts. But the five-year-old in me wants to see if I could beat O’Brian’s lighting draw!

—John Langellier

I’ve been studying Wyatt for more than 70 years. I first became interested in 1946, when Henry Fonda played him in My Darling Clementine. I saw him made larger than life by Hugh O’Brian. Then I watched his character debauched in that sorry 1960s film, Doc, a time when it was “cool” to tarnish heroes. I briefly let myself be influenced by Frank Waters’ The Earp Brothers of Tombstone. Over the past 20 years with True West, I had the good fortune to meet and read writers like Casey Tefertiller, Jeff Morey, Doc Roberts and John Boessenecker. They are not just good writers but researchers extraordinaire.

Wyatt Earp was a sporting man, much like his peers. He had flaws (don’t we all), but he was a strong character, head and shoulders above those who tried to take him down in Tombstone. He is best described by what Louis L’Amour called “a good man to ride the river with.”

—Marshall Trimble

I emphatically say yes! Although he was human and had his flaws, as do we all, and as so eagerly elucidated by many modern-day authors who have picked apart the minutiae of his life in every way possible, he must be judged by the morals of his time, and not modern-day ideals. There is absolutely no question that he and his brothers were exceptionally brave men and not to be trifled with. Even the harshest of his critics must admit that. When I think of Wyatt, I think of his 1896 quote—“He is like a sheep dog, feared by the flock and hated by the wolves,” and then try to imagine if I could muster the courage to take a stand against superior odds as he had so many times in his lifetime. Sadly, I fear not…. Could you?

—David de Haas

He was never a hero to me. Wyatt Earp was a fascinating frontier figure, with some bad spells mixed with strong leadership. From Kansas to California, Arizona to Alaska to Nevada, he was a presence. In those eras, he was someone to consider. At the faro tables of Tombstone, the mining claims of Idaho, or the Dexter Saloon in Nome, Wyatt Earp was given more consideration than other folks. Hero worship? Not necessarily. This was just being smart. The novels, movies and television presentations may have exaggerated parts of his career, but in the day, wherever he was, Wyatt Earp mattered.

—Don Chaput

When I was a kid, I wanted to be Wyatt Earp—well, at least Hugh O’Brian’s version of him. I wanted to be brave, courageous and bold (and wear cool Western clothing). But I grew up, got into the Old West field, and discovered that the real Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp was not all the small screen cracked him up to be. I came to know researchers who dug up the dirt—the pimping, the cons, the gambling, etc., etc. And, lo and behold, this flesh-and-blood Wyatt became ever more interesting than the cardboard cutout hero. And maybe that’s the important thing. I have few “heroes” when it comes to the Old West, men (or women) who I aspire to be like. Wyatt Earp sure isn’t one—but I could study him, read about him, even digest the popular culture image of him, for days on end.

—Mark Boardman

I’m glad to admit that Wyatt Earp is one of my two favorite Old West characters, along with “Comanche Jack” Stilwell. I love the whole Wyatt Earp story.

Hero? I don’t know in what regard we might use that term for Wyatt. Lake, Burns and other early writers did a pretty good job of putting Wyatt in that light, as did the 1950s TV show and movies such as Tombstone. However, with the advent of the Internet and historic newspaper websites, we’ve learned a good bit about Wyatt that has put him in a less-than-heroic light. Documented history often changes one’s perspective from previously held opinions.

However, I’ve never had a hero who didn’t have “feet of clay.” Wyatt did, and so did virtually every other lawman of the Old West. Wyatt’s story is one that keeps us going. Long May His Story Be Told!

—Roy B. Young

THE LAST WORD

When I was 10, Wyatt Earp was my hero. He could do no wrong, and like the song said, I believed he was flawless. Then a series of historical breakthroughs changed everything.

“Wyatt Earp is now relegated to the trash heap of history.” So pronounced two prominent historians who had uncovered evidence in 1959 that Wyatt Earp’s second wife—who he had abandoned—had turned to prostitution and committed suicide with an overdose of laudanum. Oh, and on her deathbed she was quoted as saying: “Wyatt Earp ruined my life.”

And then it got worse. But let’s go back to the beginning of the myth-making process.

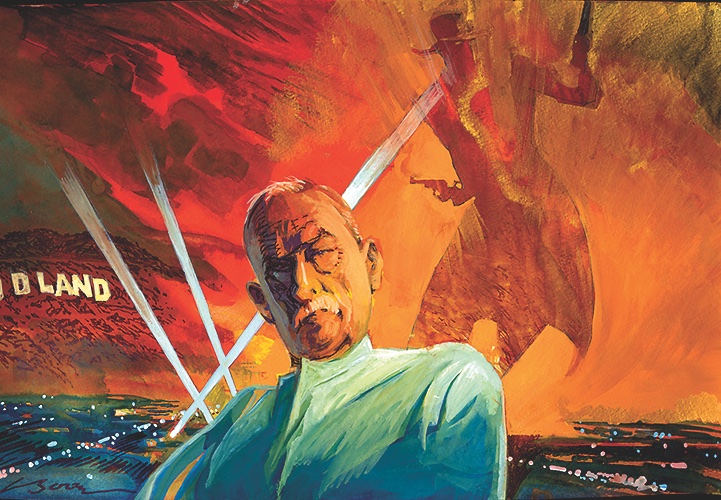

Thanks to authors Walter Noble Burns and Stuart Lake, Wyatt Earp basically came out of nowhere in the 1930s, and after this initial discovery period, he then had a huge resurgence when Stuart Lake sold the Earp-as-Super-Lawman idea to TV and we got the Hugh O’Brian TV show in the mid-1950s. This image held solid until researchers (like historians John Gilchriese and Frank Waters) started turning up murky, and even more shady aspects of his life, full of scandalous and sordid, edgy and violent aspects, writ large for the consumption of a very un-woke audience.

A PIMP’S PROGRESS

Then came even more damning evidence when it was discovered that Wyatt Earp had been a bouncer on a floating bagnio (whorehouse) in Peoria, Illinois, at the time he claimed he was hunting buffalo on the plains and that the census for 1872 appears to show him living in a bordello. Of course we already knew that later in Dodge City several soiled doves went by the name Earp, but this really put Wyatt in the camp of the procurers. Not a nice place for a legendary “flawless” lawman

Perhaps what we choose to believe about him says more about us than it does him. I for one no longer think of him as a hero, but I still admire his guts. But the most wonderful part of the effort to seek the truth has been meeting the fellow buffs and historians who study this history and try to make sense of it every day. That has been the true reward for me. So, thank you, Wyatt Earp, for bringing me together with some pretty brilliant and humorous people.

MY CURRENT TAKE

From my perspective today, I see Wyatt Earp in the late 1920s trying to get his story told to vindicate his felonious actions in the Tombstone part of his life (it was a mere 22 months of his long life). He didn’t want to necessarily become a heroic do-gooder, but that was what was ultimately in the cards. Stuart Lake took care of that.

From there, a crooked town (Hollywood) spun out a crooked fable that has spanned the globe. Equal parts hype, nostalgia and human longing, the old lawman stands tall and, at least on film, he vanquishes all his enemies, the facts be damned.

—Bob Boze Bell

“I will not say that all of the people in the motion picture industry are crooks, but I will say that all the crooks in Hollywood are in the motion picture industry.” -Zane Grey