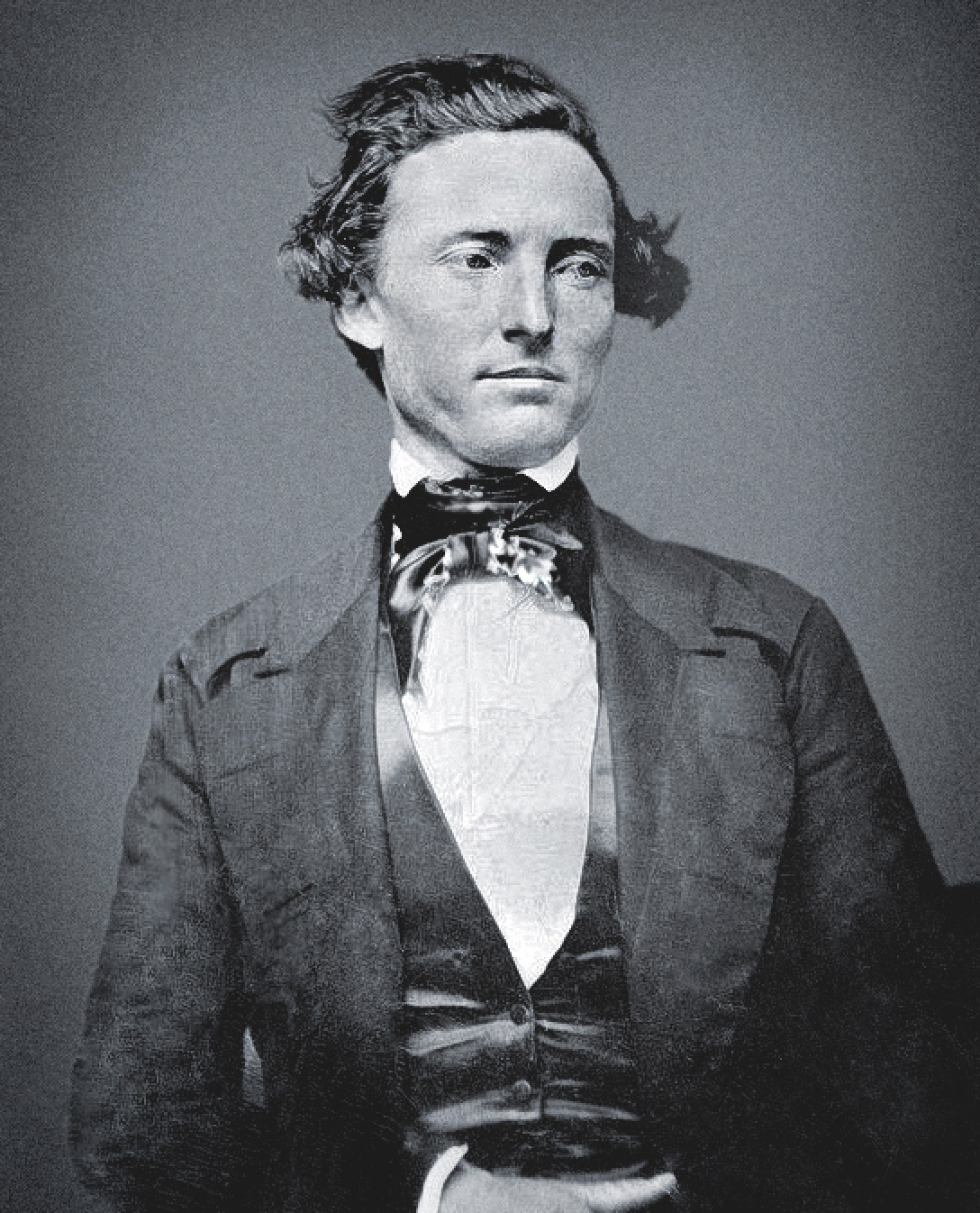

– MATTHEW BRADY, COURTESY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS –

A Texas Rangers historian reflects on one-sided history and the danger it presents to our understanding of the past—and the present.

The Texas Rangers have been fighting one foe or another for nearly two centuries. Now the world-famous law enforcement body finds itself under fire in a cultural war—and there’s already one Ranger down.

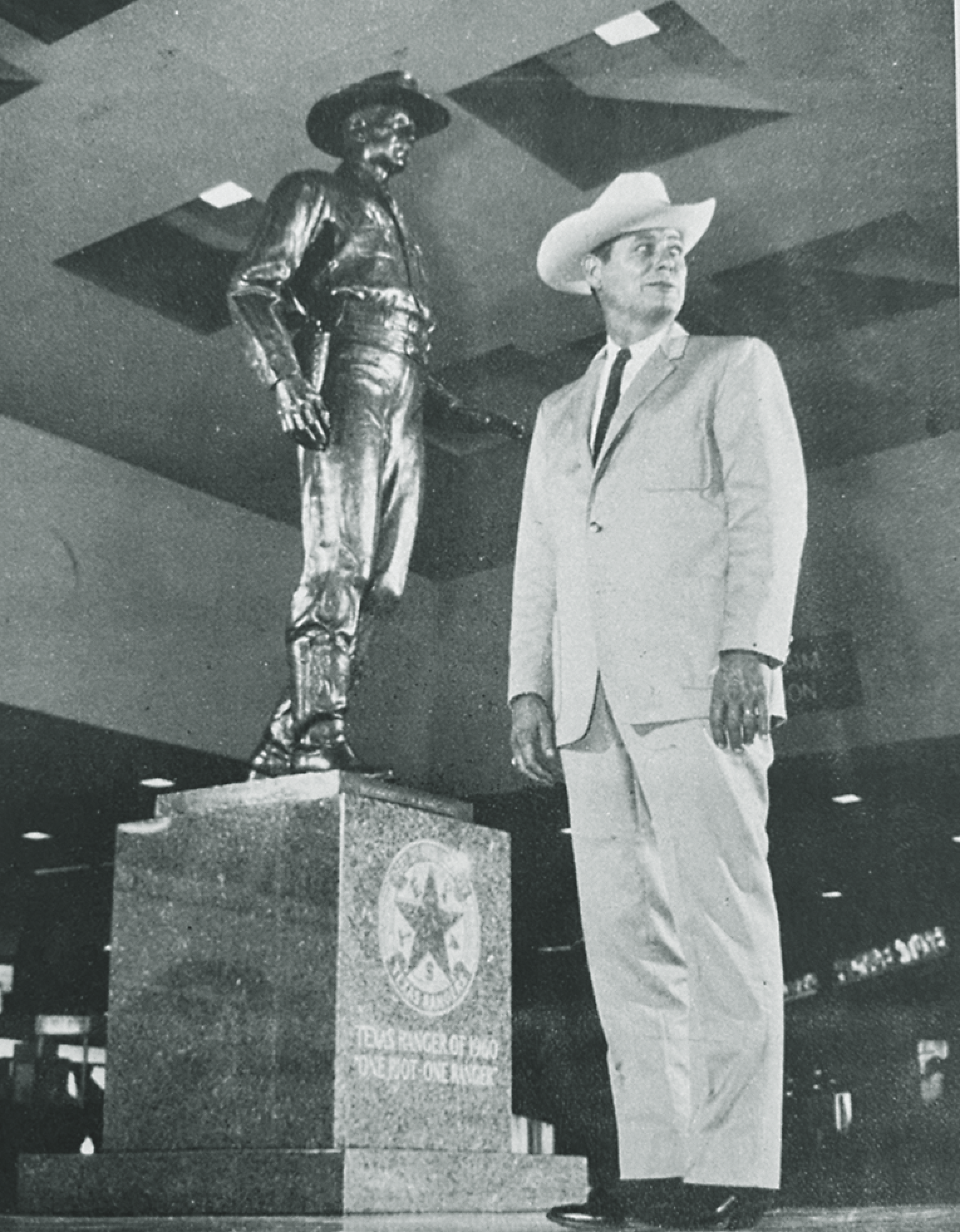

In early June 2020, the City of Dallas removed the iconic 12-foot bronze One Riot, One Ranger statue at Love Field, an airport fixture since 1963. The reason: Jay Banks, the Ranger who stood as model for sculptor Waldine Tauch, did not enforce school integration in Mansfield, Texas, in the 1950s. That is absolutely correct, but as modern Rangers still must, mid-20th-century Rangers followed orders. They didn’t unilaterally set state policy. Wrong as what happened in Mansfield was, Banks and other Rangers would have been out of a job had they not done what Gov. Allan Shivers sent them to do.

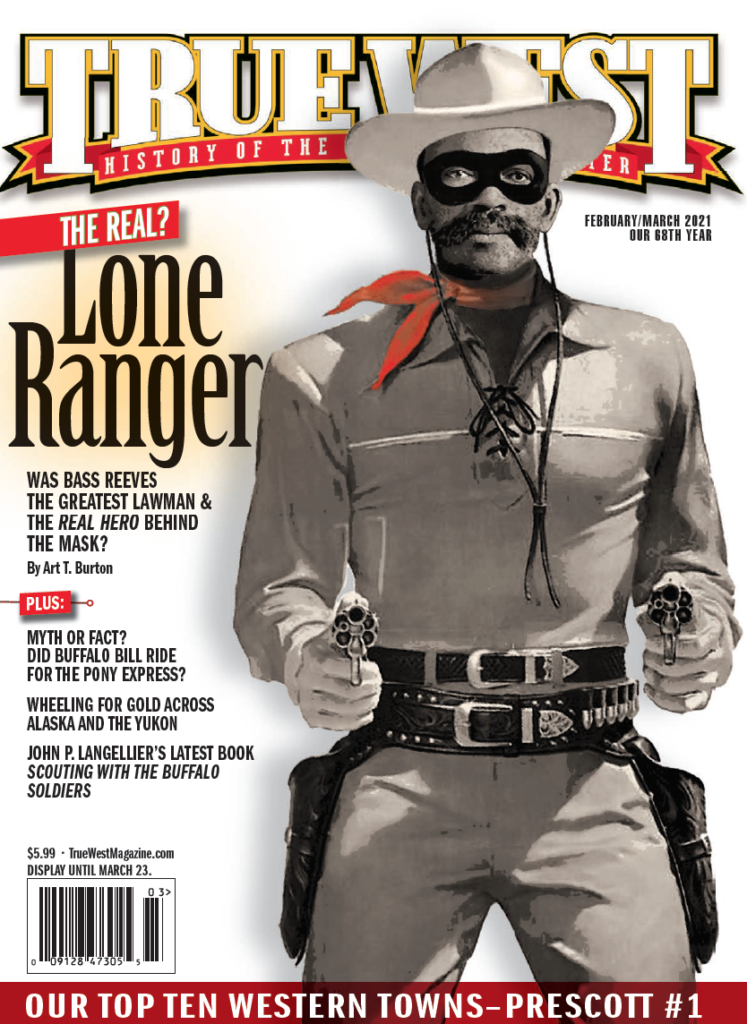

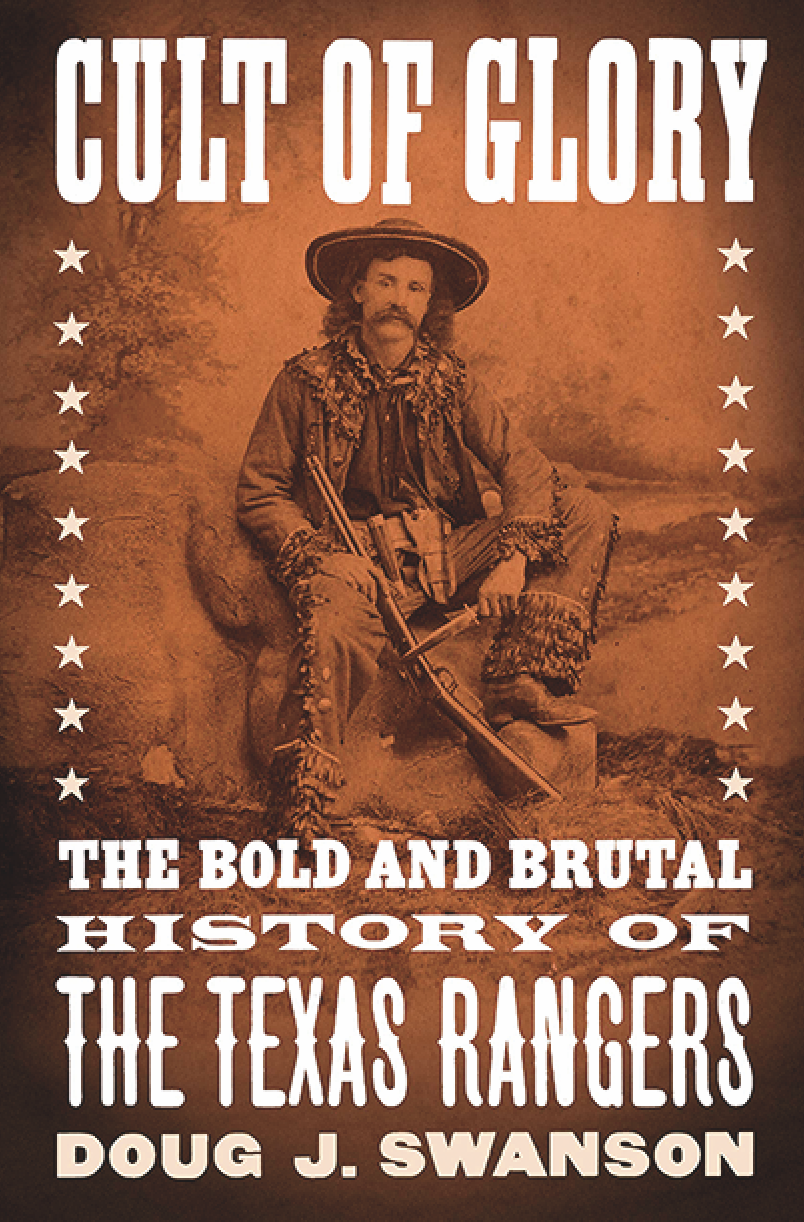

Since shortly after the establishment of Stephen F. Austin’s Anglo colony in the 1820s, the amalgamated entity that collectively came to be known as the Texas Rangers—ready- to-ride volunteers, paid militia, state or federalized troops, rough-hewn frontier lawmen, worthless political appointees, crooked state cops, honest state cops and finally, well-trained professionals—have mostly looked for trouble, pursuing hostile Indians to thieves and killers. This time, however, trouble has come to them, primarily in the form of a new, thought-provoking, and well-written if mostly one-sided history of the Rangers by Doug Swanson, Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers (Viking, $28).

Anyone who has read other Ranger his- tories knows that the Rangers were often violent, sometimes inept, sometimes nothing but rogue killers and sometimes corrupt. But not all. They also did good— they rescued captive children, they recov- ered stolen horses and cattle, they arrested (or killed) wanted outlaws, they escorted surveying parties, they protected and policed transcontinental railroad workers, intercepted bootleggers, brought order to oilfield boomtowns, took down corrupt government officials, captured bank robbers and solved cold-case homicides.

One of Swanson’s main themes is that over the decades the Rangers have carefully cul- tivated their image. That’s both true and not true. The Rangers certainly have had some showboaters—from frontier days to the modern era—who never minded being quoted or photographed, but many more kept a low profile and in fact abhorred publicity. (No question, this was sometimes for good reason.) The Ranger myth, while irrefutable, was more an evolving creation of the popular culture and news media than a deliberate Ranger strategy. Today, however, much like Marines, Rangers are quite aware of their reputation and none of them want to be the one to bring embarrassment to the force.

– COURTESY AUTHOR’S COLLECTION –

In Cult of Glory, primarily using secondary sources, Swanson mostly focuses on Ranger abuses (admittedly often horrific) of American Indians, Mexicans, Blacks and labor organizers with only occasional mentions that they often did the right thing. Like the history of the Rangers, the book is not error-free. On page 62, the author has Samuel Walker in 1844 facing off with a

Comanche “wanted for arrest.” Rangers had no law enforcement power at that time and would not have been having a hand-to-hand fight with a hostile Indian they intended to take into custody. On page 197, in discuss- ing the noted Ranger Capt. Leander McNelly, Swanson says Western writer Zane Grey based his novel Lone Star Ranger on McNelly. That’s incorrect. Researching his book, Grey spent time in and around El Paso with Ranger Capt. John R. Hughes and dedicated it to Hughes and his men.

If our society is to have a reasonable and productive conversation about what was wrong or right about our history and what can be done about it today, this book certainly offers ample fodder for the “what was wrong” camp. But it lacks balance. The late Western writer Elmer Kelton put it well in “My Kind of Heroes,” his 1994 speech at the Texas State Historical Association, “There is a dark side to our history. But those who see it only in terms of the warts are as one-sided as those who see only the glory.”

Mike Cox is the author of 30-plus nonfiction books and five books on the Texas Rangers.