Shot-for-shot, Bob Boze Bell captures what C.S. Fly missed 140 years ago.

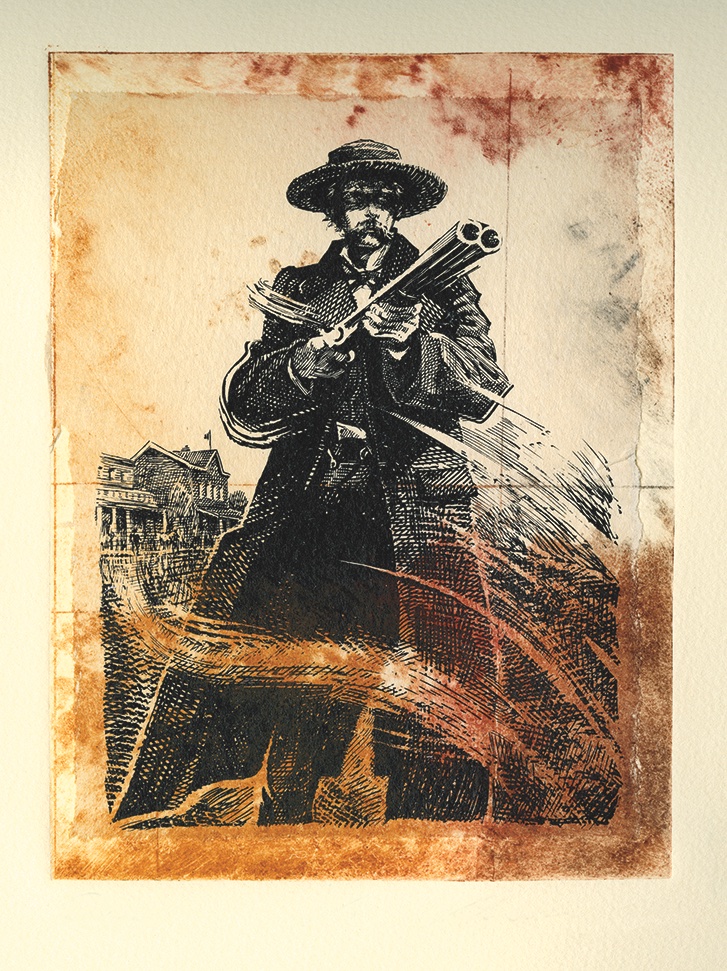

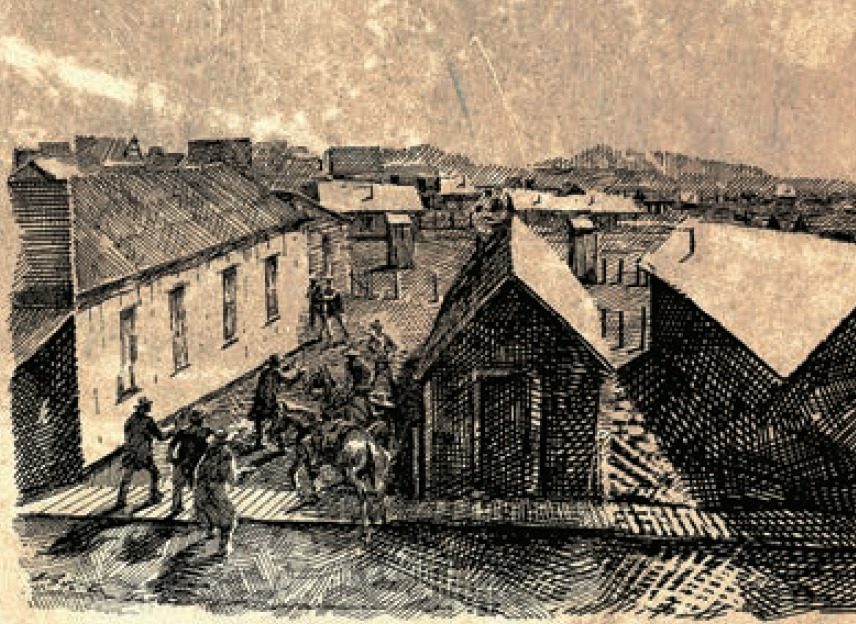

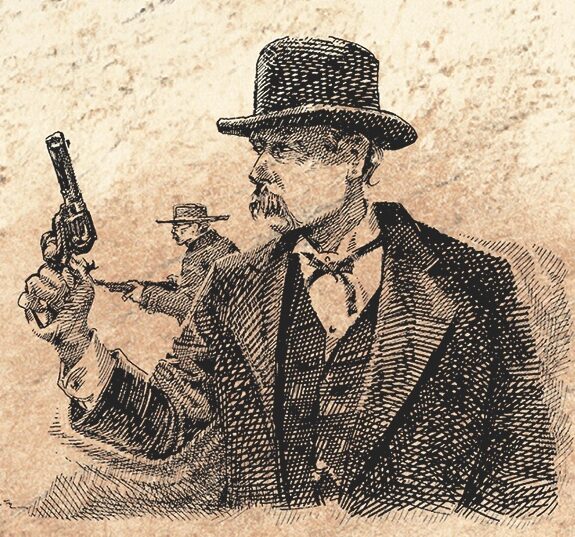

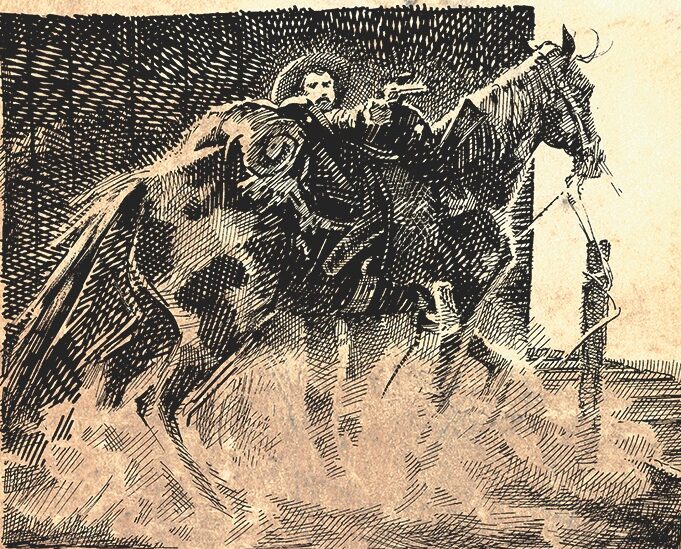

All Artwork and Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell

All photos, unless otherwise noted courtesy True West Archives

WHERE’S THE PHOTO?

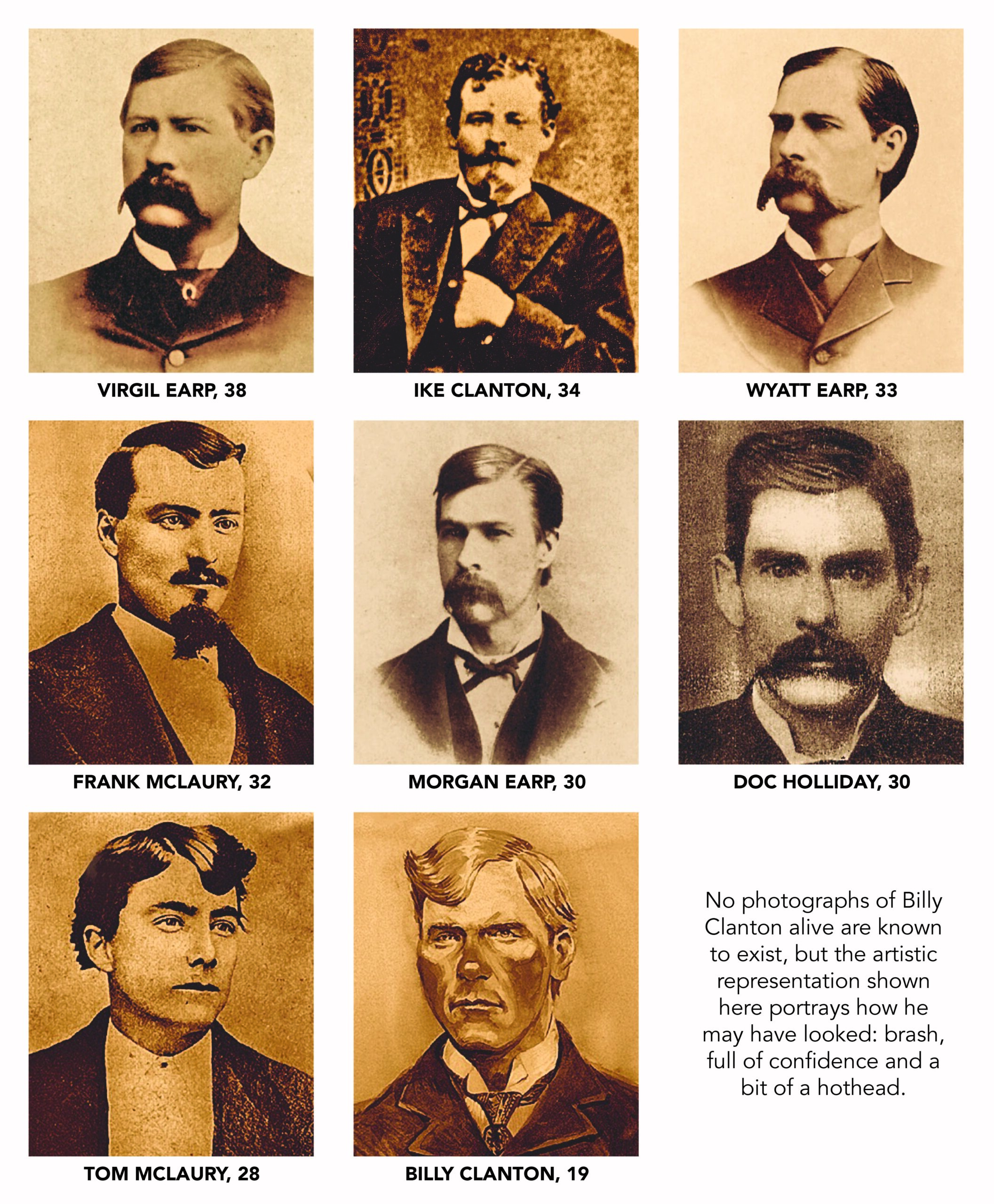

October 26, 1881, in Tombstone. One of the most celebrated events in Old West—maybe American—history. Eight men face off in an empty lot behind the O.K. Corral. Thirty seconds. Thirty bullets. Three die. Two are severely hurt. One is grazed. Four run for the hills. All march into history and legend.

Where’s the photo?

C.S. Fly, a prolific and (with his wife, Molly) gifted photographer who ultimately takes some of the great shots of all time. His studio abuts the empty lot to the south. The Earps and Doc Holliday have their backs to his building, just feet away. But no photo of the gunfight.

What happened? Well, apparently Fly was caught by surprise (the whole town was, including the participants). He was doing something else as the guns went off. He didn’t have time to set up his equipment. And when silence came to town, Fly had another calling—to go into the lot, to check on the participants. He took the gun from the hand of a dying Billy Clanton. And then the bodies, living and dead, were removed. And maybe Fly was too stunned to think of photographing the bloody grounds.

So, no photos—until the next day, when Fly captured the bodies, well dressed and laid out in coffins, of Cowboys Frank and Tom McLaury and Billy Clanton.

Thus, the Old West field is left wishing that things were different, that Molly or C.S. Fly had been prescient enough to have a camera ready to go when the gunfight began.

Even then, a photo would have been just an image of one moment in time. It couldn’t tell the whole story. It could not paint the perfect picture.

This is what artists have been doing for more than 120 years—trying to paint (or sketch) the perfect picture of the Tombstone street fight. They’ve taken the various oral and written accounts, the evidence, the analysis compiled since 1881 and mixed it into colors to be placed on the canvas (or whatever material they choose).

Our own Bob Boze Bell is one of the premier chroniclers of the fight. Since his first attempt at age 12 (don’t ask how long ago that was), he estimates he’s tried several hundred times to paint/sketch/scratchboard the shootout (including the lead-in events, the aftermath, and the participants). Bell figures he’s gotten more accurate as time has passed and more information on the gunfight emerges. Some are little details, like Tom McLaury’s silver hatband, or Wyatt Earp carrying his pistol in an overcoat pocket. But they’re important, if for no other reason than many viewers (or potential buyers) know those little facts and expect them to be correct.

As noted, a piece of art, like a photograph, is a snapshot of a specific moment in time.

Unlike the photo, though, it goes through the filter of the artist’s mind and arms and hands and fingers. A camera merely reports on what it sees. An artwork is an interpretation. That can give it more power—say, when the painting is in color and the photos of the period are in black and white. Artwork can provide perspective on events because the portrayal reflects the biases and opinions of its creator. But that also means it may not be entirely accurate, so historians have to take it with a grain of salt and a dollop of skepticism.

With all that in mind, let’s look at a few of Bell’s greatest hits, O.K. Corral-style. Let’s see just how well he hits the mark.

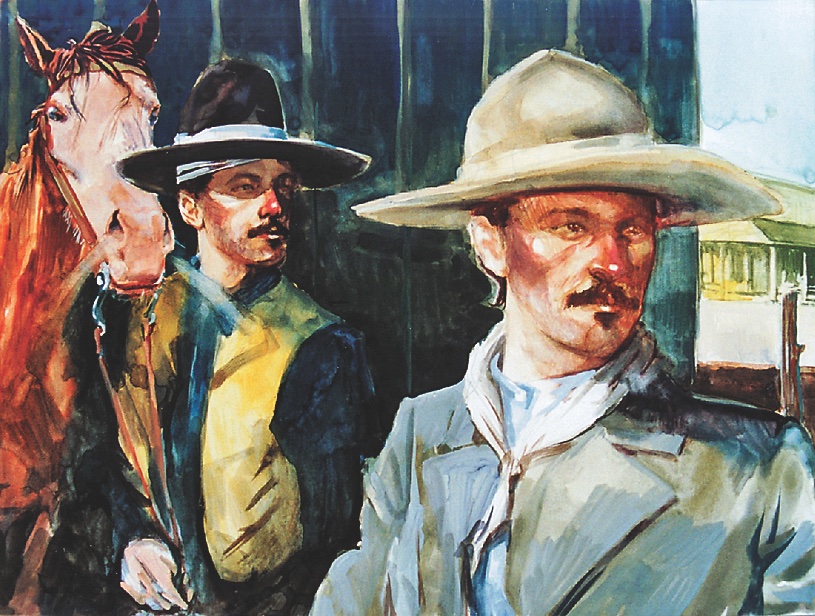

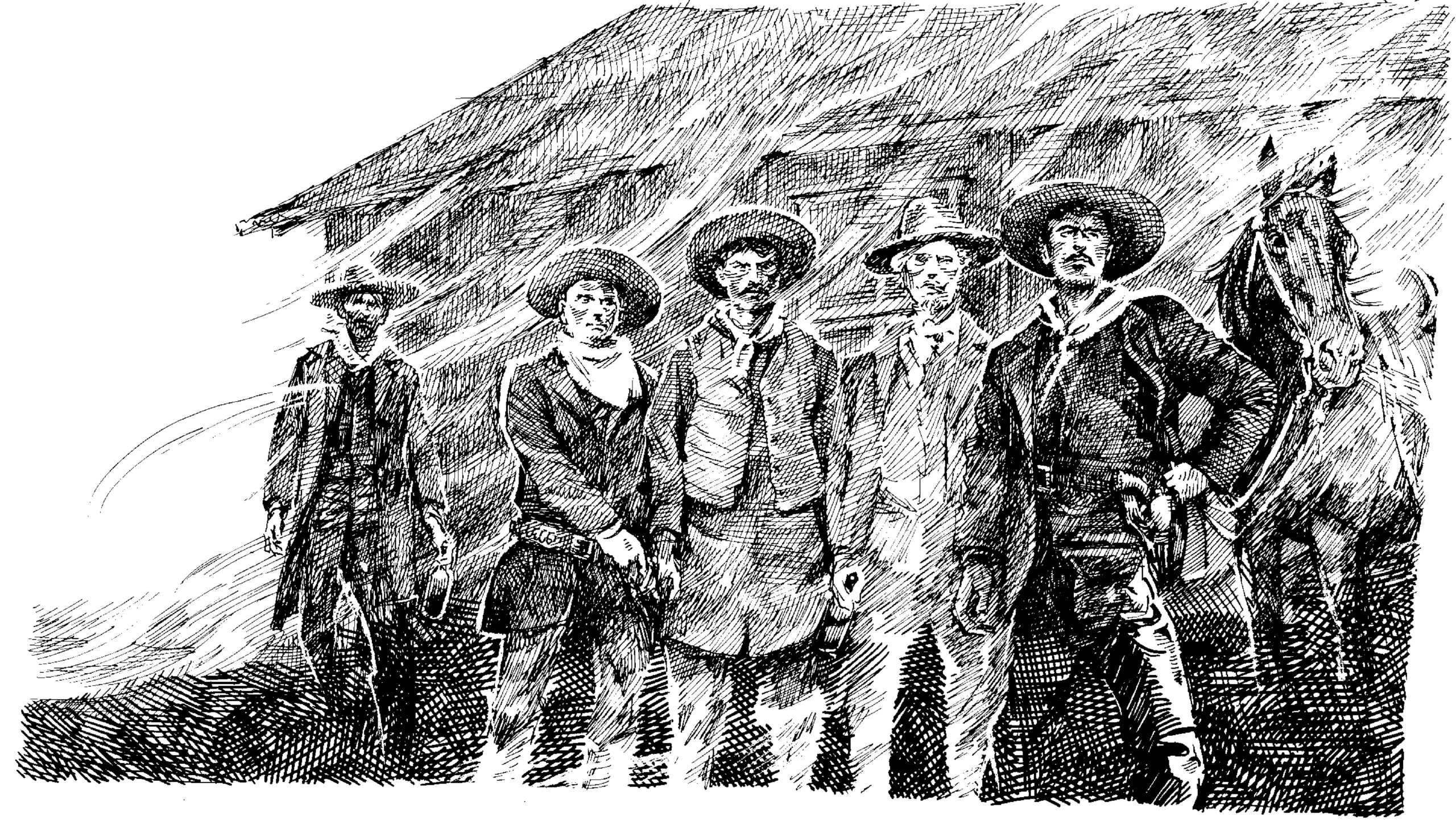

Tom and Frank (upper left) anticipate the motive of the oncoming Earps. Note the silver hat band detail on Tom’s hat.

The Cowboys (top) had regrouped west of the O.K. Corral rear entrance, just beyond Fly’s in the side yard, outside the window where Doc is boarding.

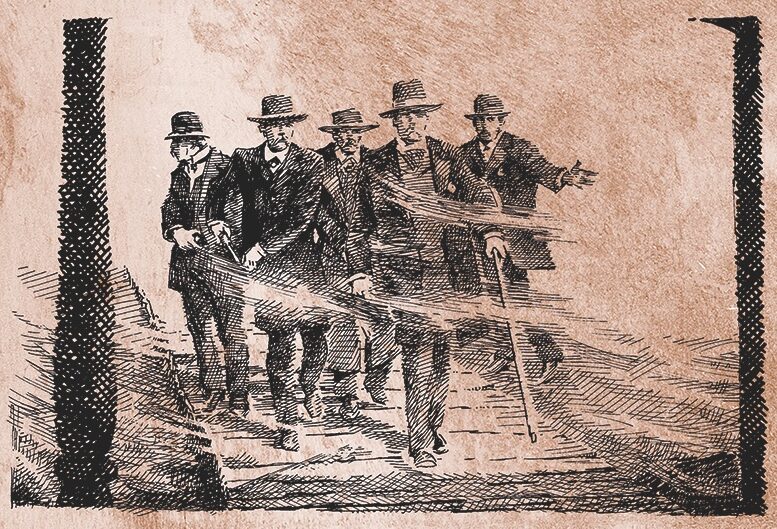

When Sheriff Johnny Behan confronts the Earps and Doc (middle) with the news that he has disarmed the Cowboys, Virgil and Wyatt both pocket their pistols, but the four men continue toward the Cowboys.

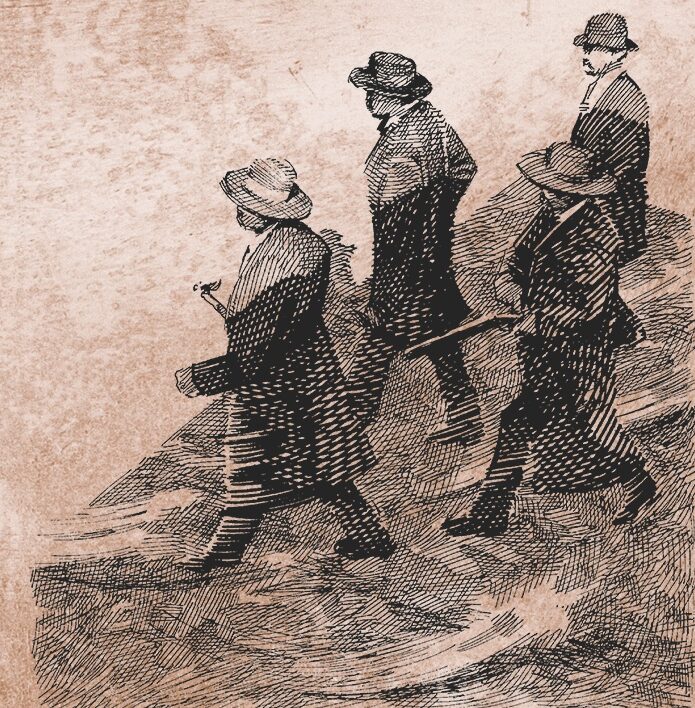

Virgil and Wyatt walked ahead of Doc and Morgan two-by-two (left) as they entered the vacant lot.

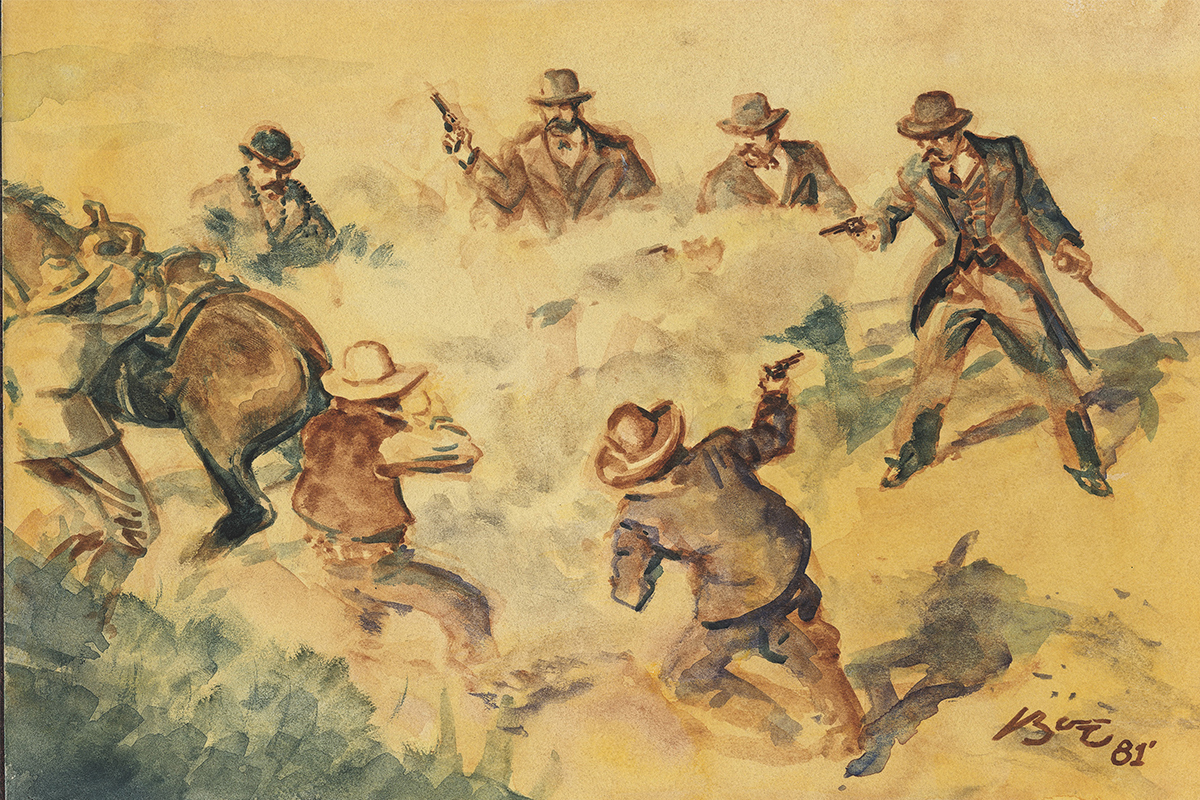

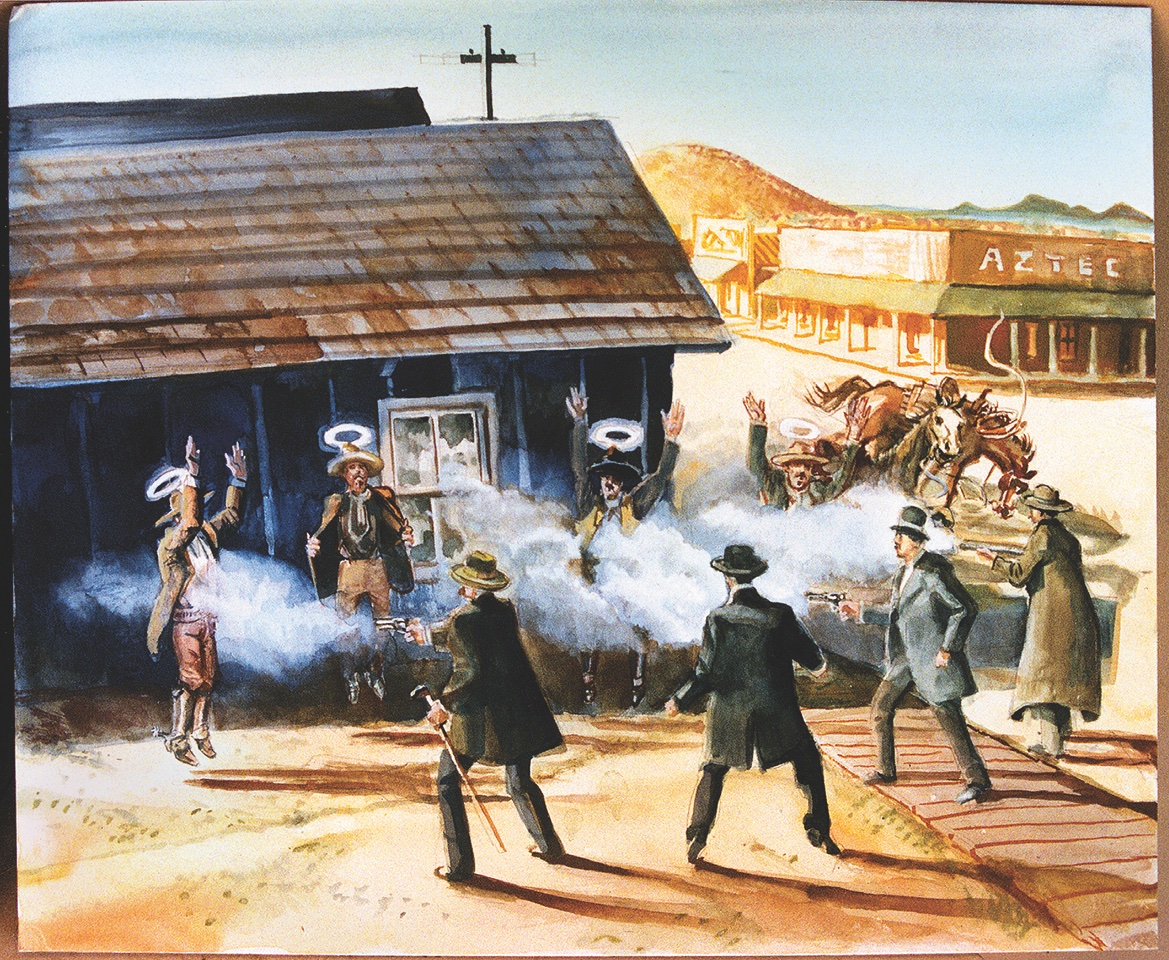

A COLORFUL DEPICTION

The first is one of the artist’s better-known paintings of the street fight (page 28). It is a depiction of many moving parts. Billy Clanton is at the extreme left, falling into the Harwood House wall as Marshal Virgil Earp, directly across from him, fires away. Just beyond Billy, two horses are rearing in terror at the gunfire and sudden movements. Tom McLaury is out of view, behind one of the horses, probably trying to reach for a rifle in a saddle scabbard. Doc Holliday is barely seen to the right of the horses; he’s leveling a shotgun, trying to get a clear shot at Tom.

Frank McLaury is up next—for the moment. He’s already been gut-shot, but that hasn’t taken him out of the fight. He’s hit Morgan Earp (on the ground) with a bullet that went through his shoulder and damaged his shoulder blades. Wyatt has a protective stance over his brother while firing at Tom McLaury’s horse.

There’s more blood to be spilled over the next 10 to 15 seconds—but that is for another painting.

And to be honest, there are many well-known parts not covered by this painting. But this painting does what it’s supposed to do: provide a colorful look at a historical event, as conceived through the eyes and mind of a talented artist who is also a history nut.

Bell has also covered almost every movement, hour-by-hour of the participants in the street fight on October 26, 1881. He has meticulously done his research for over four decades, even re-staging the events and the gunfight participants with re-enactors in historical locations. With tension and drama, his black-and-white, duotone and color illustrations capture every perspective of the Earps and Holliday, the Cowboys and the streetscapes of Tombstone on that fateful October day. His sketches and illustrations vividly capture the points of view of all the combatants and visualize the scenes of the day, including Virgil’s dramatic proclamation, “Hold on, I don’t want that!” just before the first shots are fired.

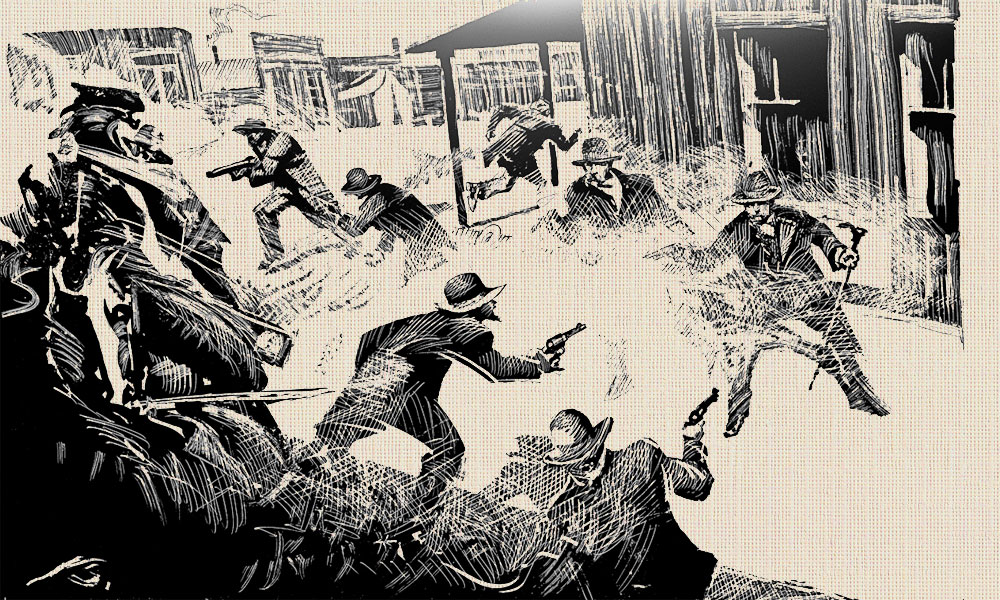

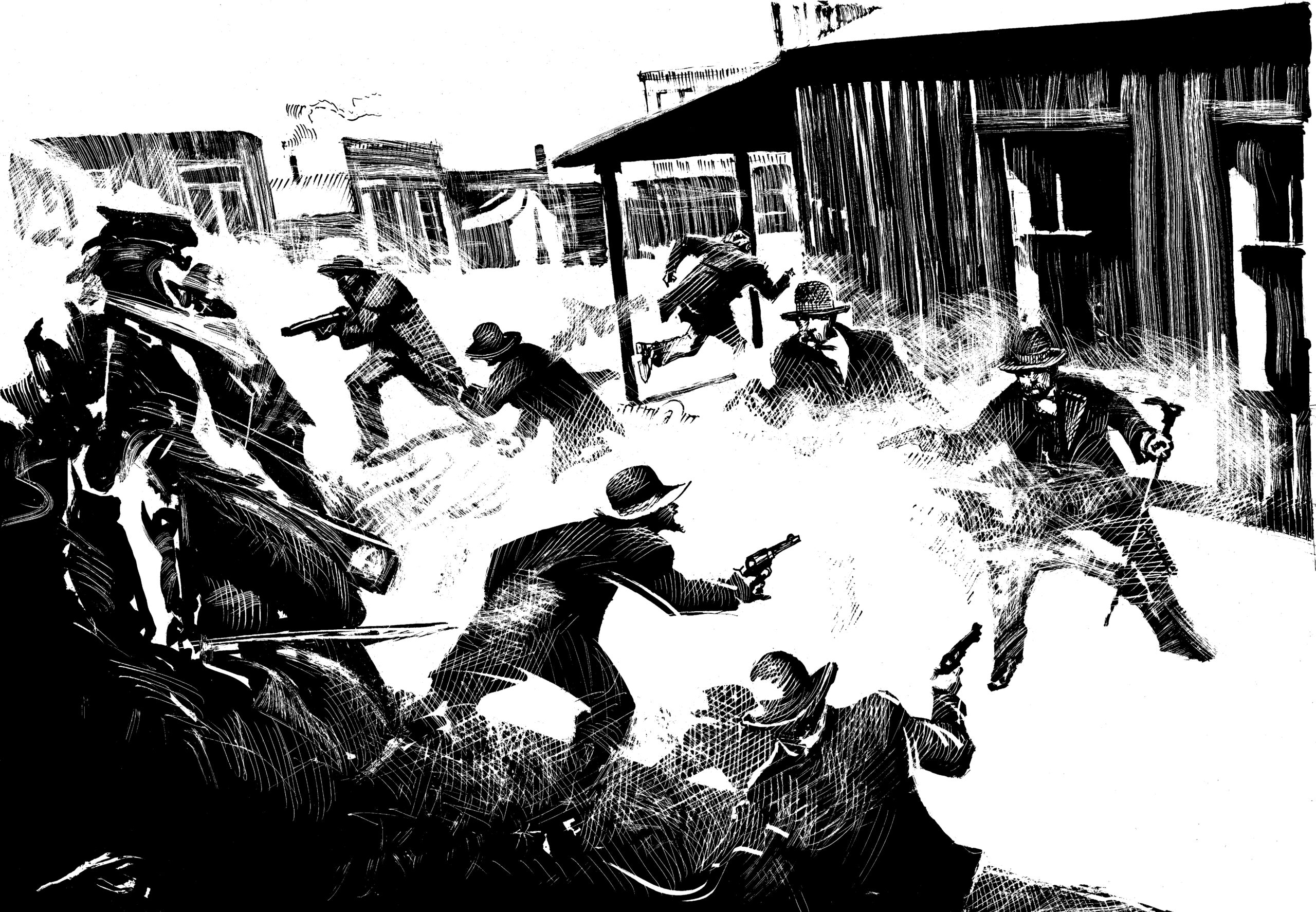

THE BLACK-AND-WHITE DEPICTION

Bell has done hundreds of black-and-white pieces on the street fight. One of his best, captures the shootout (page 28) just seconds before the moment captured by the color piece—he believes that this one may be one of his best in terms of accuracy. Note that Ike Clanton is hightailing it toward Fly’s, escaping the carnage that he helped start.

Morgan Earp is going down after being shot in the shoulder by Tom McLaury. Wyatt and Virgil Earp are firing at Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury, both of whom are shooting at the lawmen. Doc Holliday, the closest to Fremont Street, is using his shotgun to get after Tom McLaury, who is obscured by his horse. At this point, it appears Billy Clanton is going down after being hit a couple of times. There’s no indication that Frank has yet to put a bullet in Virgil’s right calf

The gunfight is about half done.

A couple of other observations. First, the gun smoke is thicker and heavier than in the color paintings—and that is more accurate, considering the testimony and the firearms of the period. Second, the faces are more indistinct, less detailed. That gives the piece a frantic, confused aspect that correctly reflects the atmosphere in the empty lot on that cold afternoon. None of these guys were anticipating a shootout; they really didn’t want one. So it was a surprise when the guns went off; the adrenaline started racing, and all were acting out of instinct—not through knowledge or experience. Which is why two-thirds of the 30 shots fired missed their mark.

Sure, black-and-white automatically means that something is missing in the interpretation—color. But it has its own striking feel and presence. Which does the artist favor?

“I don’t have a preference. I just want to get it right and be authentic,” Bell says. “Except when I’m being snarky and want to make a point.”

Which brings us to…

“I had my pistol in my overcoat pocket, where I had put it when Behan had told us he had disarmed the other parties. When I saw Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury draw their pistols, I drew my pistol.” -Wyatt Earp

HOW OLD ARE THE GUNFIGHTERS?

–Addie Bourland

BLOW-BY-BLOW

WITNESS STATEMENTS

SNARKY AND MAKING A POINT

Bell has done the fight “six ways to Sunday,” as he says. Generally, the pieces are connected by the search for accuracy. But occasionally, BBB will turn things around a bit to make a point—Boze-art, let’s call it.

One such effort (which is also one of the artist’s favorites) shows the Cowboys with their backs quite literally against the wall of the Harwood House (above). Their hands are raised in surrender. Only two of them, Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury, are armed, and both weapons are holstered. As the two sides face off, Virgil Earp orders the Cowboys to throw up their hands—and they immediately comply. The Earps and Holliday then open up on the men, getting off five shots before the Cowboys can return fire. This is not a gunfight; it’s a massacre, a murder. And to emphasize this viewpoint, our audacious artist has placed halos over the heads of the Clantons and McLaurys.

BBB illustrates the question, “Were the Cowboys unarmed victims in the gunfight?”.

BBB’s black-and-white illustration of the street fight captures the intensity of the deadly confrontation as the shooting started. And, yes, that is Ike Clanton beating cheeks, top center.

This is based on the testimony of Ike Clanton at the so-called Spicer Hearing into the incident, which took place just days later. Others, including Sheriff John Behan, support that view. But it didn’t wash with Judge Wells Spicer. The bullet wounds suffered by the Cowboys could not have happened if their hands were raised. And if this scenario was accurate, how the heck did Ike Clanton walk away unscathed? He helped inflame the situation with his boasts and threats—and yet Wyatt Earp allowed him to make a run into Fly’s? That’s part of the reason that the Earps and Holliday went free.

Oh, and as to those halos? Our artist is making a point: “I did that to show how ridiculous the idea is that they were choir boys. That is satire, not authenticity.”

Bell excels at satire (in all media and in person).

THE BOTTOM LINE

The bottom line: works of art are the closest thing we’ll get to a real depiction of the events of October 26, 1881 (excepting re-enactments). And, for many, that may not be enough. We live in an age when we can use a smartphone to video all sorts of events—catching all the action, all the people, all the elements. Some such videos have made their own sort of history in the last few years. So we’re spoiled. Our expectations are way out of whack, especially when it comes to the past.

Sure, there are movies. But Hollywood has shown an aversion to accuracy when it comes to the “O.K. Corral” (heck, even using that name is way off). The wrong people die or are wounded. The gunfight goes on for 10 minutes, and dozens of shots (or maybe more) are fired. The list goes on and on and on. Many of us have given up on Westerns to tell the true story of the Tombstone street fight.

Billy Clanton (far left) slams against the Harwood House, while Virgil (right and below) fires at him. Behind Virgil, Morgan has been hit and is down while Wyatt shoots at the withers of Tom McLaury’s horse. Frank McLaury is about to fire—he will hit Virgil in the calf.

No doubt, art from people like Boze Bell is limited in what it can do. It probably can’t depict all the movement without blurring the people. It can’t show the reality of gun smoke without obscuring the entire picture. We can’t know the exact facial expressions of the participants—placid? Stern determination? Pain? Frozen terror? A painting can’t capture the noise and the smells associated with the gunfight.

Still, artwork can spur further pictures of the mind that help fill in the gaps, that extend the image both forward and backward. It can move us to imagine what Tombstone was like on that day. And most importantly, it can spur us to investigate the people, places and events that made southeast Arizona so fascinating at that time. The history is out there, in words and more, available to one and all (including through magazines like this). And the art, when done well, adds a great deal to the experience of exploration.

But with all that said…there’s always the inclination, the desire, to go back in time, visit the photography studio next to that empty lot, find the proprietor, grab him by the lapels and shake Buck Fly to his core:

“Where’s the photo?”

Mark Boardman is the features editor at True West, the managing editor of The Tombstone Epitaph, and pastor of Poplar Grove United Methodist Church in Indiana.