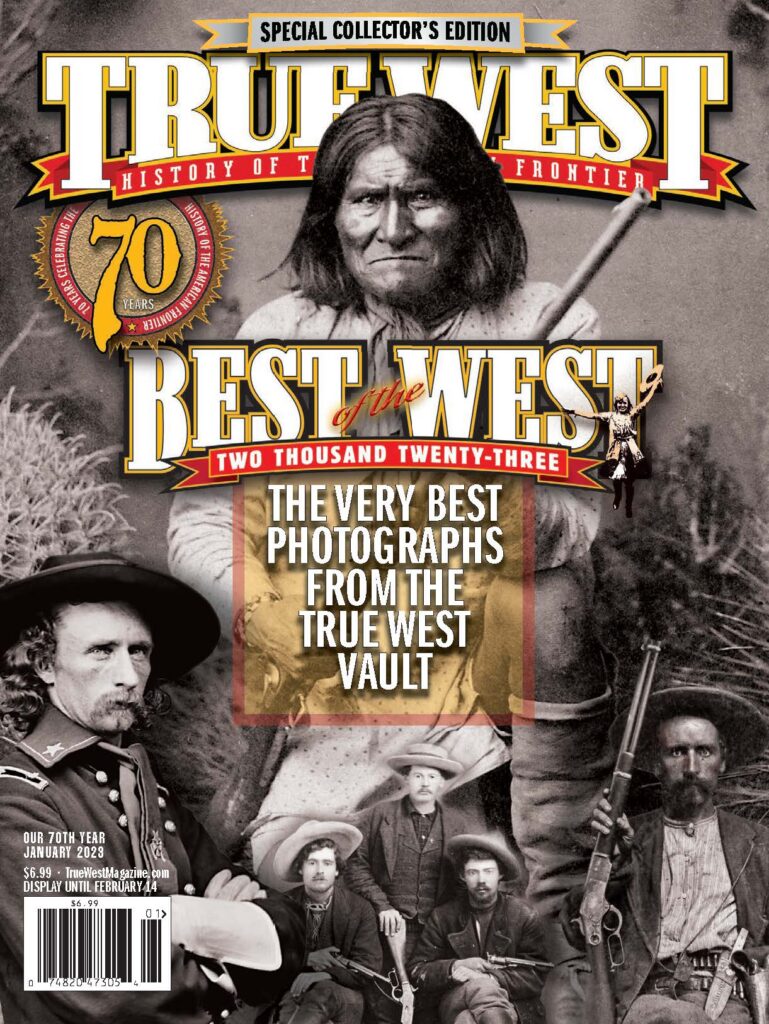

The very best historical photographs from our treasured vaults define our idea of the West.

In honor of our 70th year, the editors of True West have invited our contributors to offer their choices for the most emblematic photographs taken in the West. The portfolio reflects the authors’ interests in Western history and offers a window into their individual perspectives. The photo essay also is an introduction to a year-long commemoration of True West’s 70th anniversary and the very best photography of the West from the 1840s to the 1940s. We look forward to your perspective as we look back together at the images and image makers that spark our imaginations, trigger our emotions, elicit our empathy and drive our desires to learn more about our Western past.

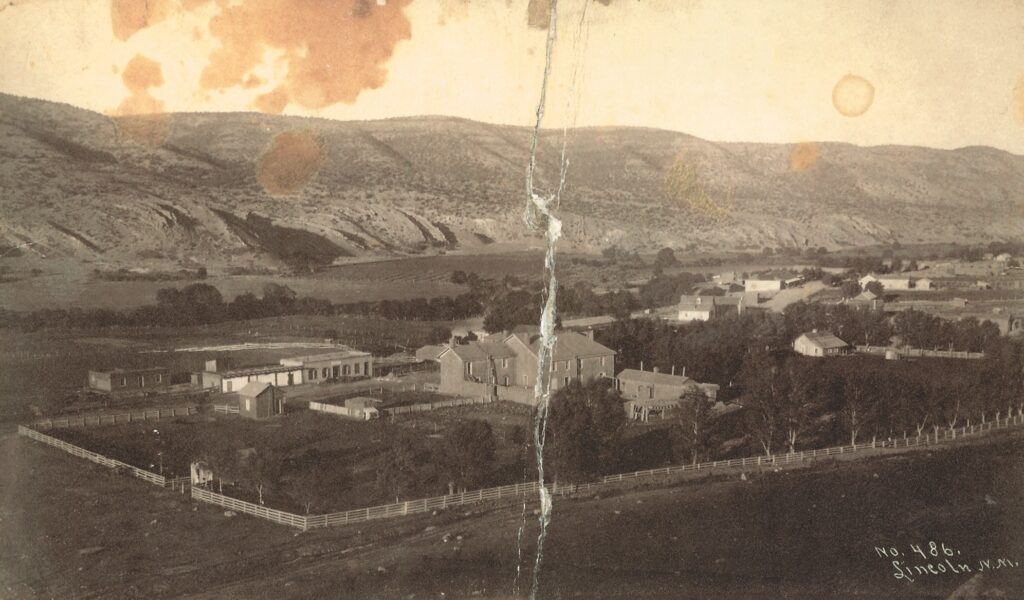

Lincoln, New Mexico, circa 1880sIn many respects, the town that Billy the Kid knew is still there, a living history for visitors from around the world. —Mark Boardmanar, thousands of free Blacks and former slaves such as this unknown man, enlisted in the U.S. Army and were sent West as part of six newly formed all-Black regiments, where they earned the nickname Buffalo Soldiers. —Stuart Rosebrook Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University

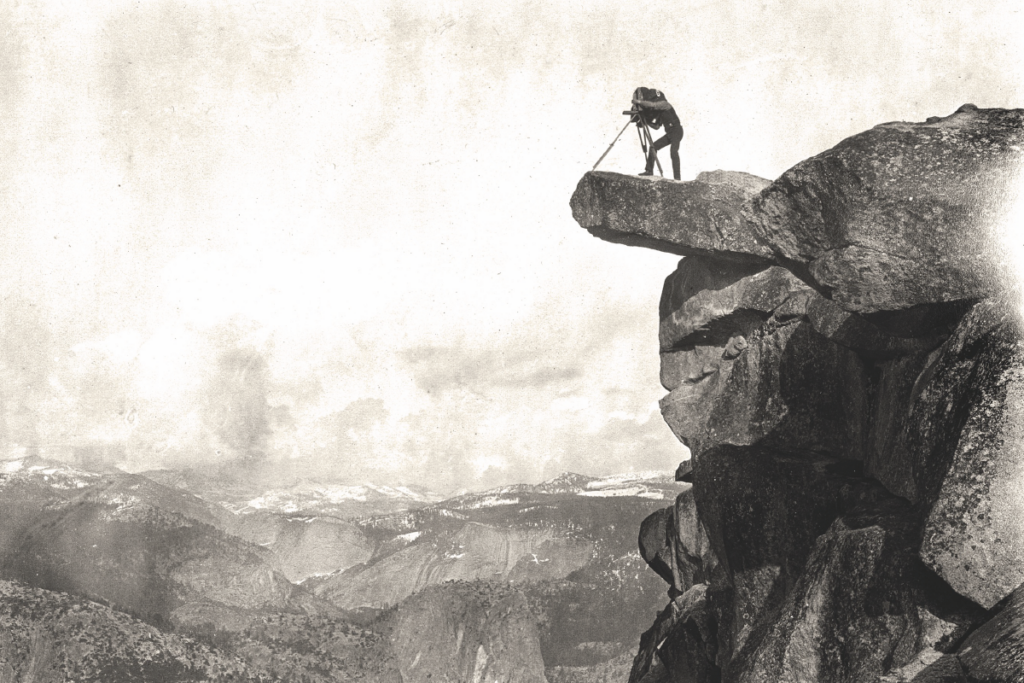

Contributor Johnny D. Boggs is a great admirer of the 19th-century Western photographers. Boggs chose William Henry Jackson’s photo of himself with his equipment on Yosemite’s Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park to underscore the nearly miraculous effort it took Jackson and his peers to get a heavy camera through that country. All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted.

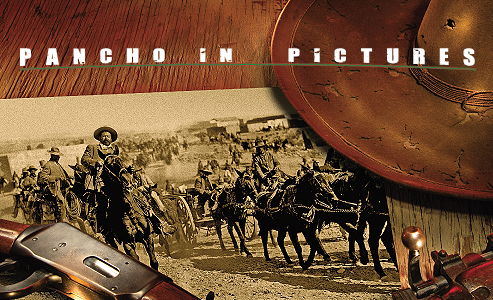

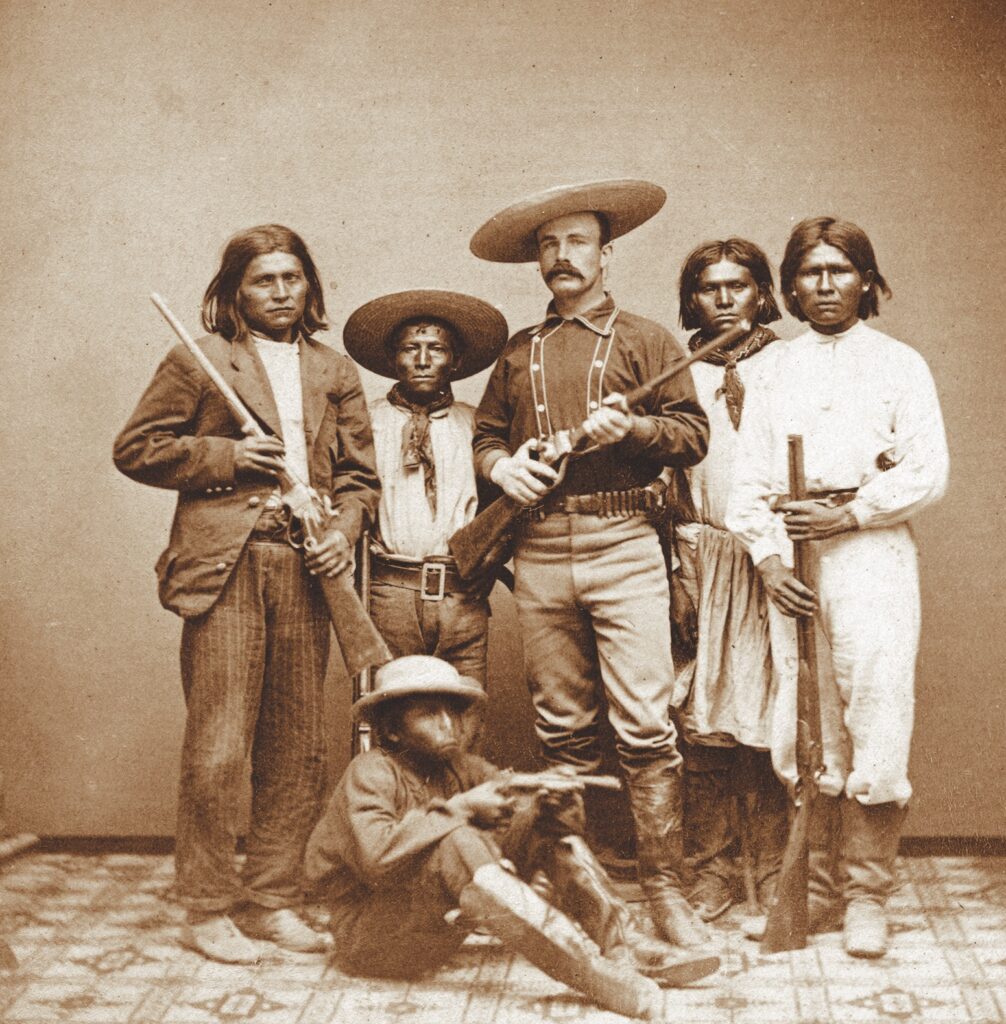

Apache Scouts

We always see the Apache Scouts in the 1886 mode, but these men, who tracked and scouted for Gen. Black Jack Pershing during the Pershing (Mexican) Expedition in 1916, represent the transitioning of a frontier army with its scouts to the modern U.S. Army/Cavalry. Their “Last Hurrah” was during this 1916 counteroffensive against Pancho Villa after his attack on tiny Columbus, New Mexico.

—Lynda Sánchez

Courtesy National Archives

Galen Clark, Mariposa Grove, Yosemite, circa 1860s

I picked up this CDV at the Las Vegas Antique Arms Show years ago, and no one knew who this grizzled-looking mountain man was. Later, I found out it is a photo of Galen Clark, the man who contributed to the writing and passage of federal legislation to protect Yosemite and the Mariposa Grove of Sequoias. Here, circa 1860s, he stands next to one of his beloved big trees, and holds his trusty half-stock muzzle loading rifle, with his “possibles” hunting bag and powder horn across his shoulder.

—Phil Spangenberger

Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection

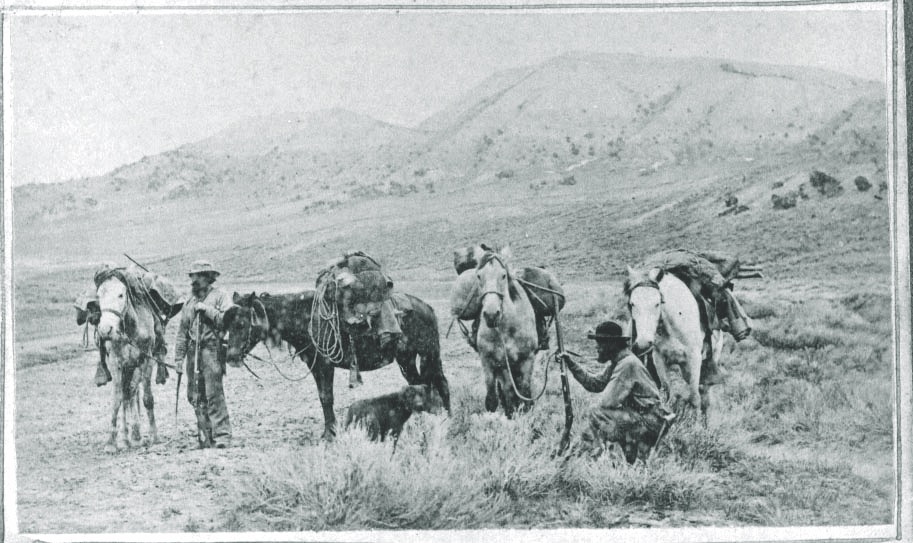

Utah Frontiersmen, circa 1860s

Photos of Westerners with muzzle loading plains rifles, like the Hawken, Gemmer, Lehman, Dimick or other front-loading guns, are seldom encountered. This image, reportedly photographed in Utah, probably dates to around the 1860s, and offers a good look at how many frontiersmen of that era looked and reveals how heavily packed out their horses were—including their saddle mounts. It’s quite a different look than what is shown in the movies—a small blanket rolled behind the cantle and a pair of flat saddlebags.

—Phil Spangenberger

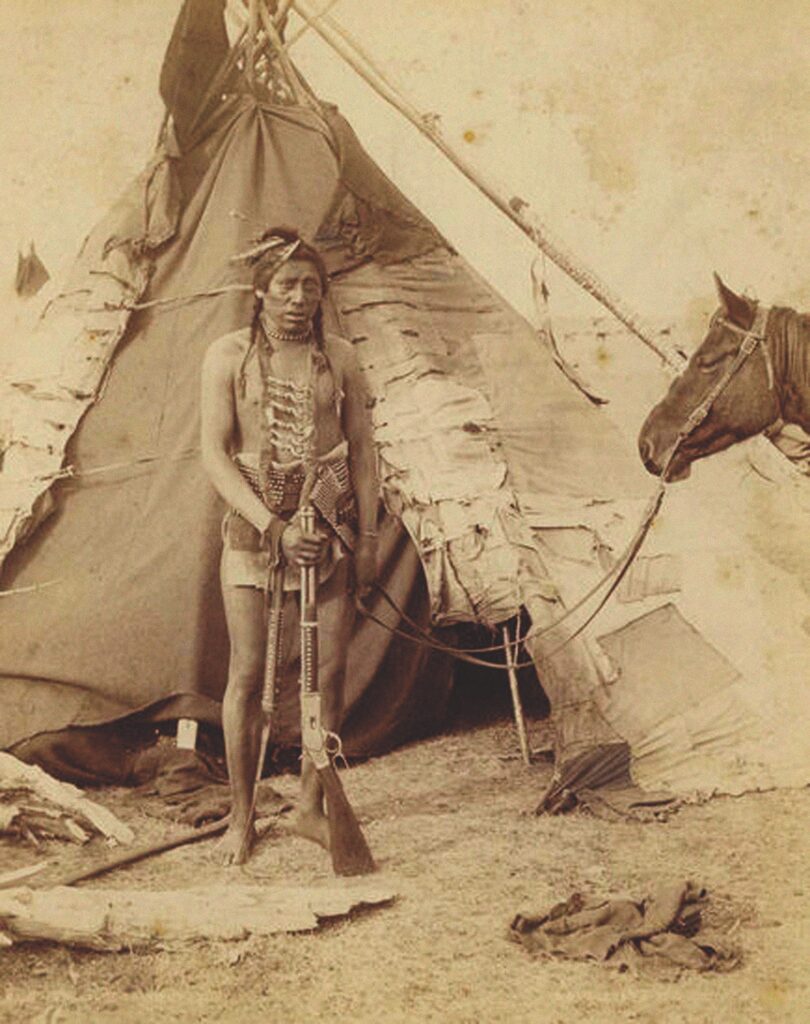

Canadian Blackfoot Brave

I’ve always considered this photo of a late-19th-century Canadian Blackfoot brave one of the prime examples of a northern Plains Indian ready for the hunt or for battle. All studded out with his brass-tacked 1873 Winchester carbine and belt full of cartridges, he’s also equipped with a heavily tacked knife scabbard, riding quirt, a necklace and bracelet, and a unique breastplate, made up of northwest trade gun brass serpentine sideplates. Even his pony’s U.S. Cavalry headstall has had brass tacks added for a more personal look.

—Phil Spangenberger

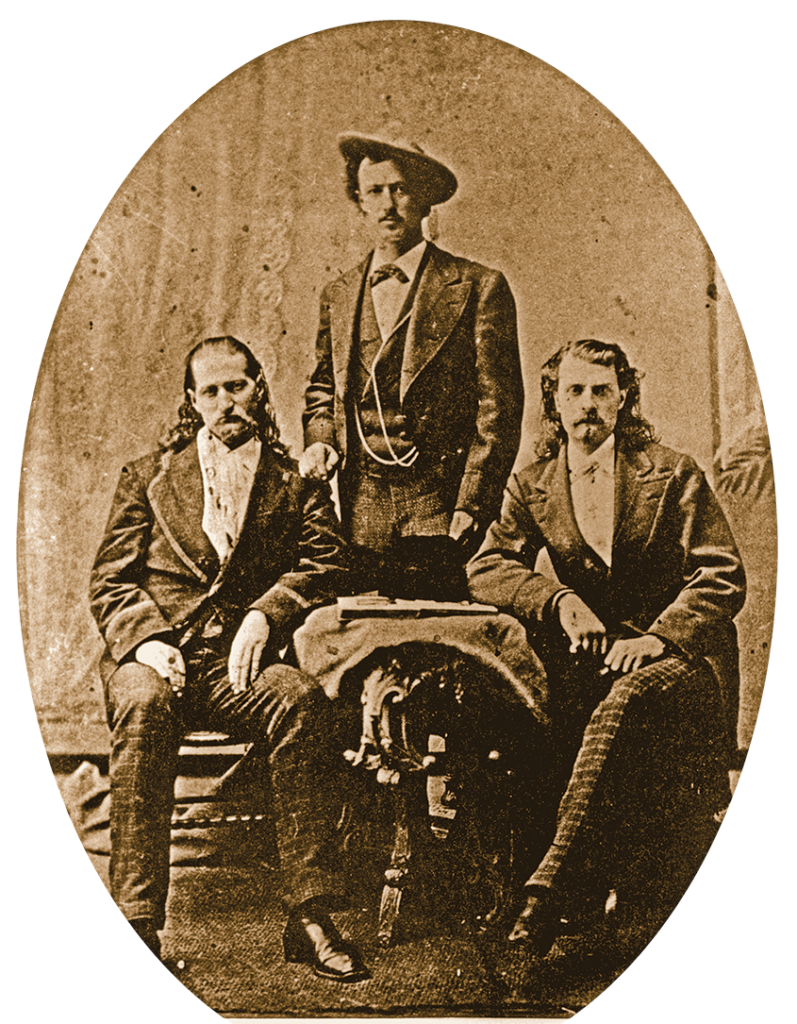

The Original Three Amigos

Wild Bill Hickok, Texas Jack Omohundro and Buffalo Bill Cody posed for posterity on their 1873-74 theatrical tour. They look like they’re already pissed off at each other.

—Johnny D. Boggs

Hickok, Omuhundro and Cody seated at the little table—The Holy Western Trinity. Only one of them will live long enough to see the 20th century…and then he lives long enough to see his memories dissolve in the mud of the trenches in Europe.

—Thom Ross

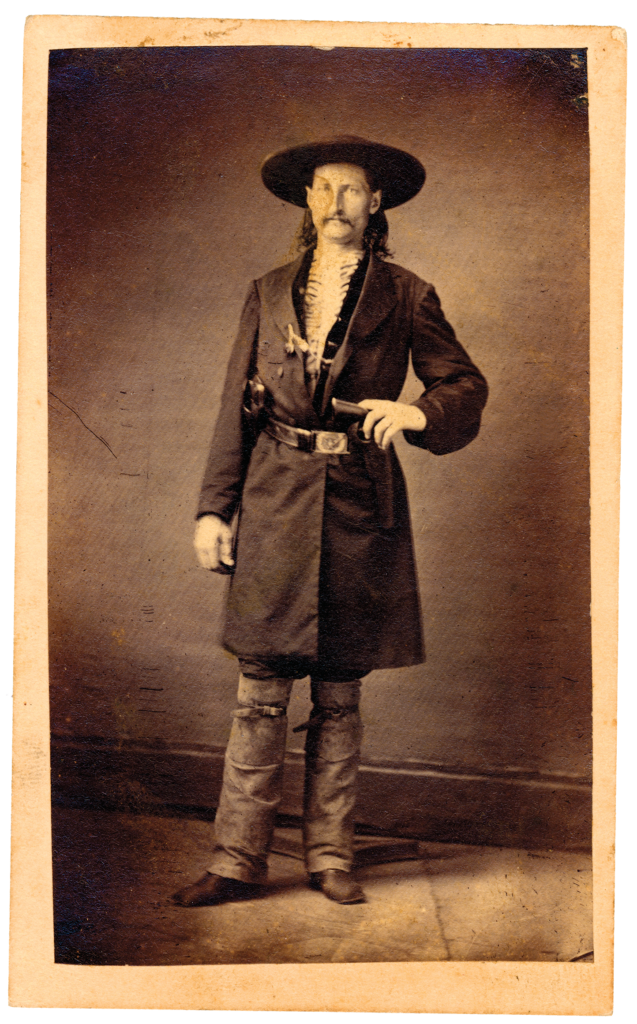

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok

This photo of James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok dispels the popular notion that the “Prince of Pistoleers” always packed a pair of .36 caliber, 1851 Navy Colts tucked in a sash. While he certainly seemed prone to use the ’51 Navy model, Hickok was known to have carried a variety of revolvers—and was undoubtedly very good with them all. This image, reportedly taken in Springfield, Missouri, around 1864, shows him wearing an eagle plate belt with a brace of holsters carrying 1860 Army Colt .44s, identified as such by the grip style.

—Phil Spangenberger

Love the leggins, the fancy shirt and the cocky stance. If you look up gunfighter in the dictionary, this photo should be there.

—Bob Boze Bell

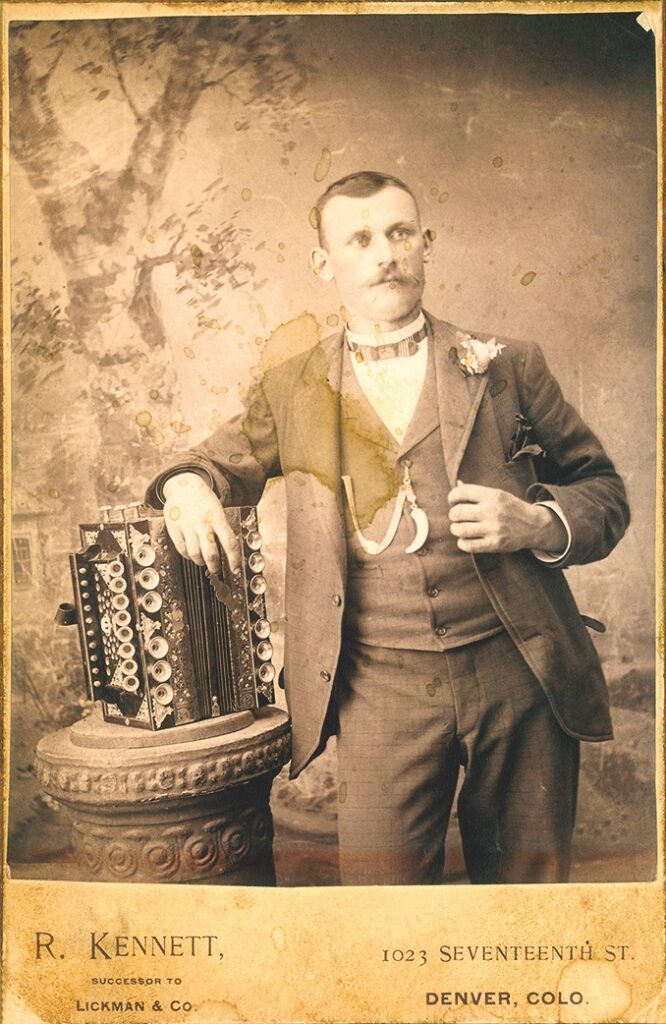

Denver Accordian Player, circa 1890 cabinet card

The highly ornamented accordion belonging to this musician sports 16 “trumpets” in the key cover and 12 in the instrument’s molding. Note the musician’s watch chain, the fob of which is a bear claw. He’s unidentified, but quite the dandy nonetheless.

—Mark Lee Gardner

Courtesy Mark Lee Gardner

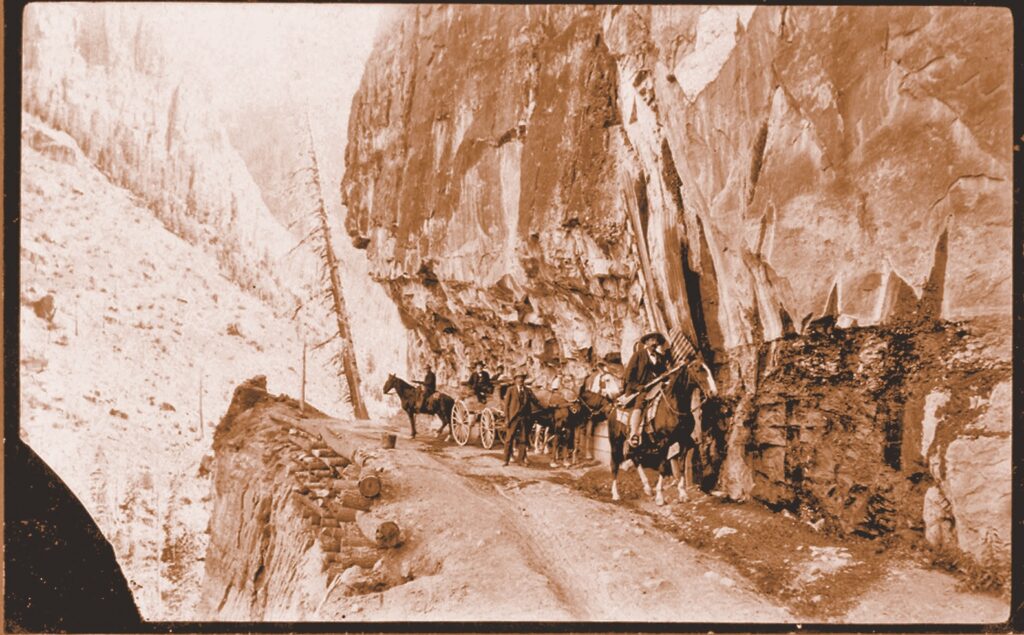

Dangerous Pass

I found this fascinating photograph in Randsburg, California, many years ago, and always wondered what the story behind it was. Who are these people and what are they carrying that required two armed guards—at least one with a Model 1897 Winchester pump shotgun? Looking at the crude mountain road where they’ve stopped to water the horses (possibly the Sierra Nevada’s Tioga Pass that originally served the nearby mining district and named around 1878 for the Tioga mine) causes one to wonder about the dangers of road construction in these rugged mountains.

—Phil Spangenberger

Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection

Cowgirl, date and location unknown

Although this pretty lady looks like a proper Easterner in her finely tailored riding habit, the adobe-wall in the background, the Western-style sidesaddle, braided horse tack and cowgirl gauntlets all boldly say Old West! We’d bet she’s likely the daughter or wife of a wealthy cattleman, and standing with that well-bred caballo, she shows that she knows her way around horses.

—Phil Spangenberger

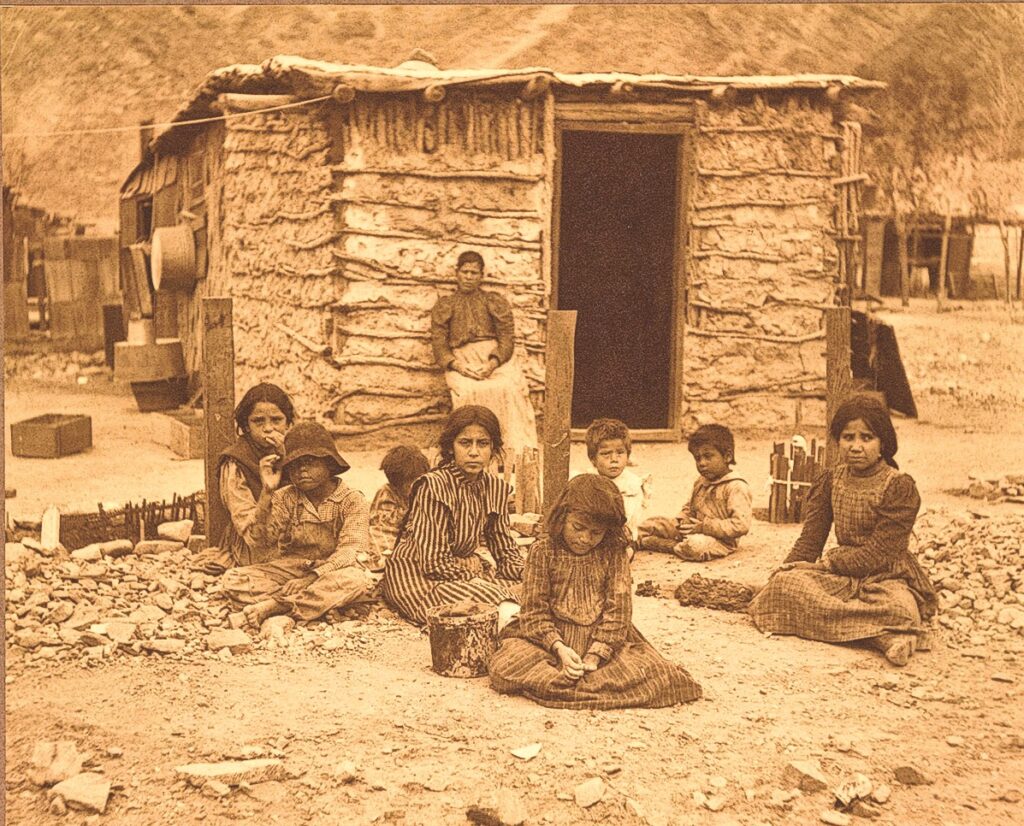

Arizona Pioneers, circa 1887

Settlers endured harsh conditions and scant home-building materials across much of the West. This Mexican-American family built their jacal of adobe, wood, cactus and stone along the Colorado River.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Courtesy Huntington Digital Library

Jack Stillwell, Army Scout

The curly-headed Jack Stilwell was the youngest member of Forsyth’s scouts and hero of Beecher Island. What Kansas boy grows up to become a friend of “Buffalo Bill” Cody, “Wild Bill” Hickok, Billy Dixon, “Texas Jack” Omohundro, and dozens more frontier scouts, plainsmen, lawmen and soldiers? His brother, Frank, turns outlaw in Arizona, and Jack meets Ike Clanton, Pete Spence, John Behan and the Cowboy clan as they try to chase and bring to justice the Earp Vendetta Posse. “Comanche Jack,” scout, deputy U.S. marshal, judge, United States commissioner…you died way too young!

—Roy B. Young

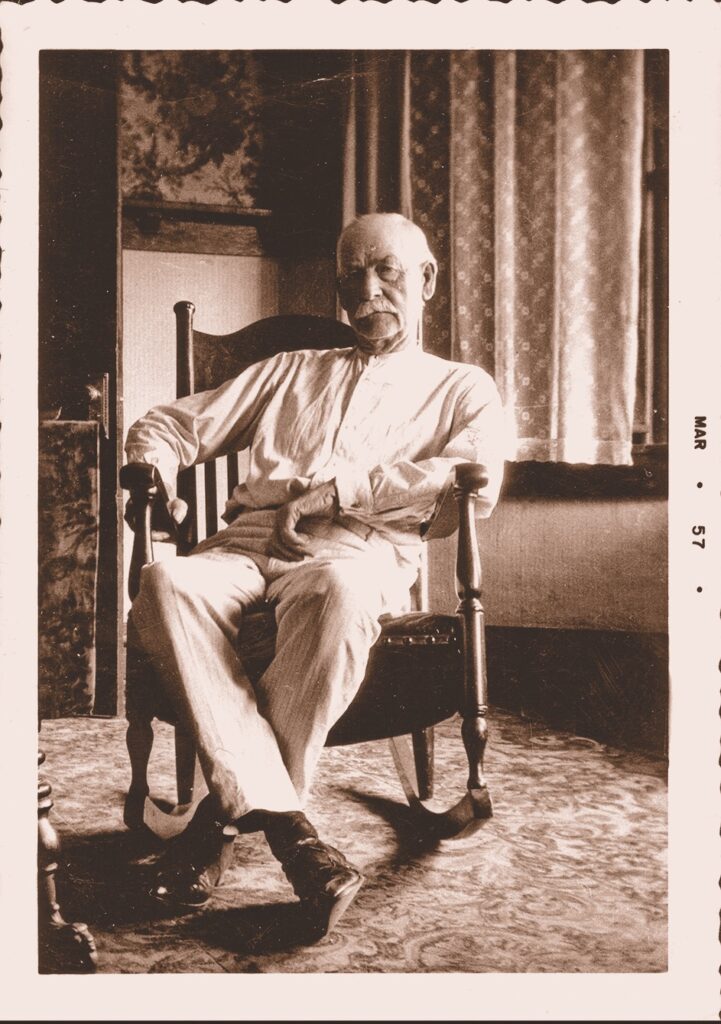

Wyatt Earp

Wyatt Earp sitting in his rocking chair. “Where did the time go,” he asks. “I sure miss seeing Doc and Bat.” “Sadie, bring me another biscuit with strawberry jam.” “If I could do it all over again, I sure wouldn’t ______!”

—Roy B. Young

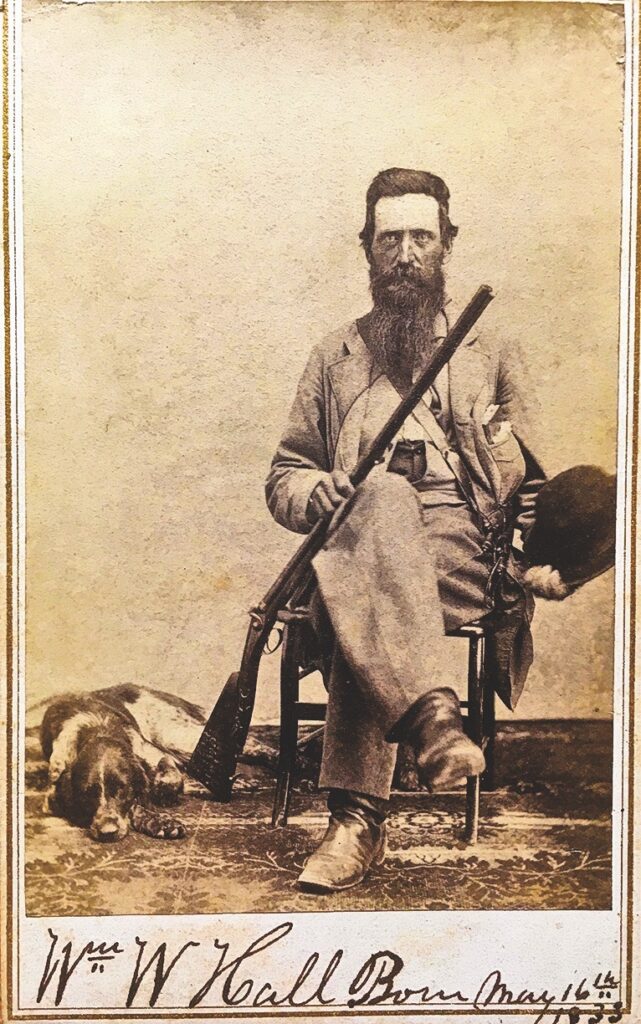

William Wallace Hall (1833-1911), photographed in Atchison, Kansas, August 12, 1867

I love everything about this carte de visite photo: favorite bird dog napping on the floor, the hat positioned just so in his left hand and, of course, the ZZ Top beard. Hall’s obit tells us he “was one of the best-known farmers in Atchison County. He was a good husband, a good father and a good neighbor.”

—Mark Lee Gardner

Courtesy Mark Lee Gardner

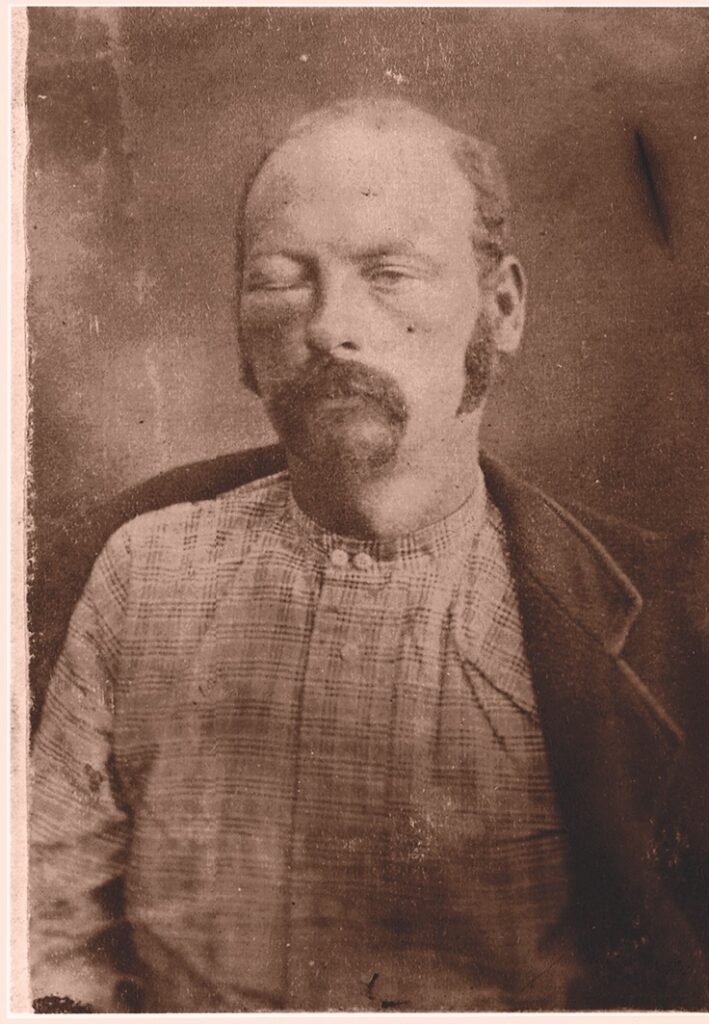

Cole Younger

How many times did this tough beat-up outlaw get shot again before this photo was taken?

—James B. Mills

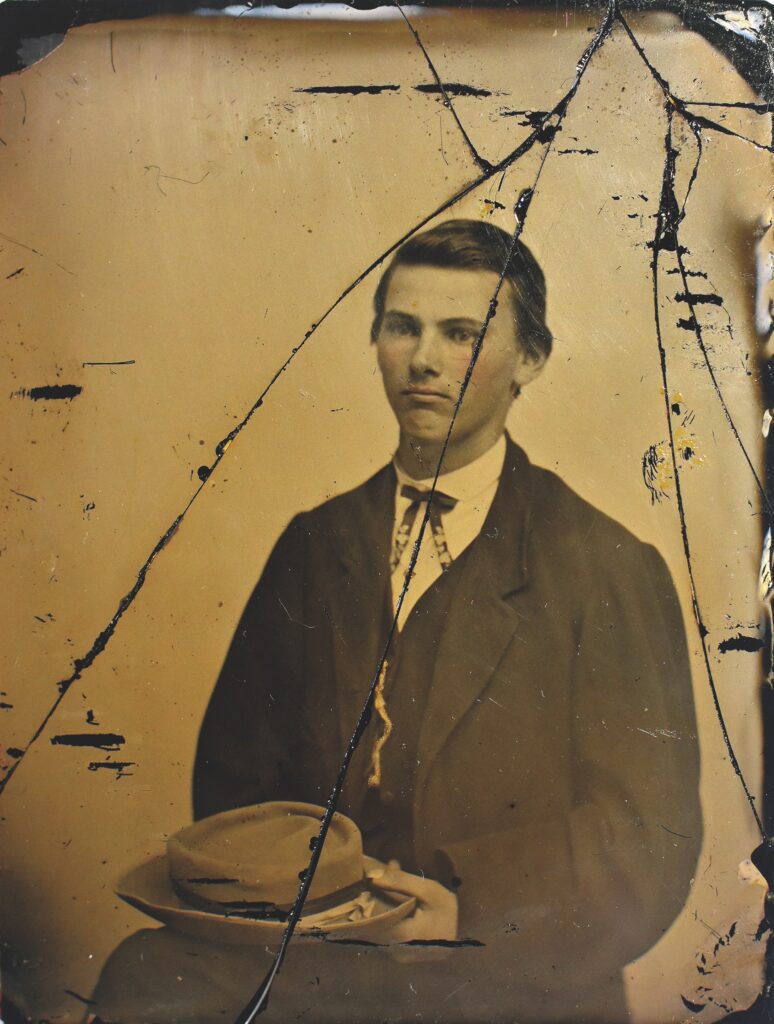

Jesse Woodson James

I was born and raised in Missouri, so Jesse James is part of my heritage. Probably my favorite “Old West” photograph, then, has to be this damaged ambrotype of young Jesse, taken when he was about 15 years old, before he’d joined the bushwhackers and well before he became a notorious outlaw. The innocence of youth is so obvious in this photo,

and I can’t help but feel sadness knowing that a savage civil war (brought about by an evil institution) will twist and warp the baby-faced youth in this photo until he is numb to violence and morality. A note on the photograph:

As stated, this is an ambrotype (an image on glass). It was likely made by itinerant photographer Thomas B. Best,

who announced his “Ambrotype Room” to the people of Liberty and Clay County in the Liberty Tribune of

November 28, 1862. Best was again in Liberty making ambrotypes in March 1863.

—Mark Lee Gardner

Courtesy of the Jesse James Birthplace Museum, Kearney, Missouri

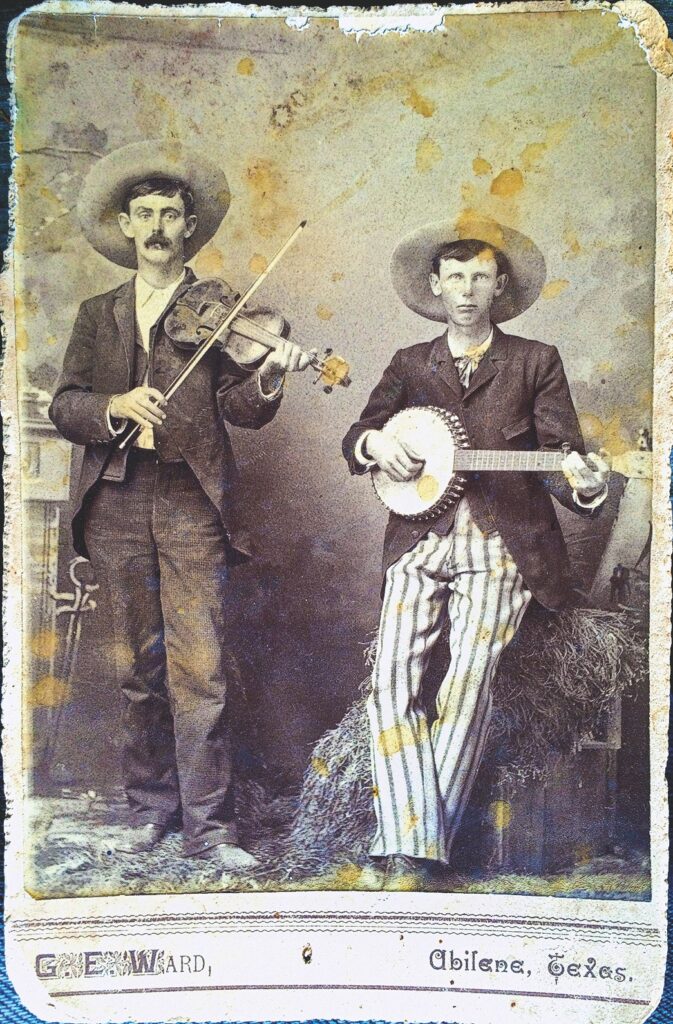

Cowboy Musicians

For several decades now, I have collected vintage photographs of musicians, primarily string instrument players (banjo, fiddle, guitar, mandolin, etc.). The favorite of my musician photos that can be considered “Old West” is this 1890s cabinet card from Abilene, Texas. Unfortunately, the musicians are unidentified, but the image is so striking that I can almost hear “Soldier’s Joy,” “Dan Tucker” and other old-time tunes coming out of that card. And, man, check out those striped britches. Yeehaw!

—Mark Lee Gardner

Photo by Gurney E. Ward, Courtesy of Mark Lee Gardner

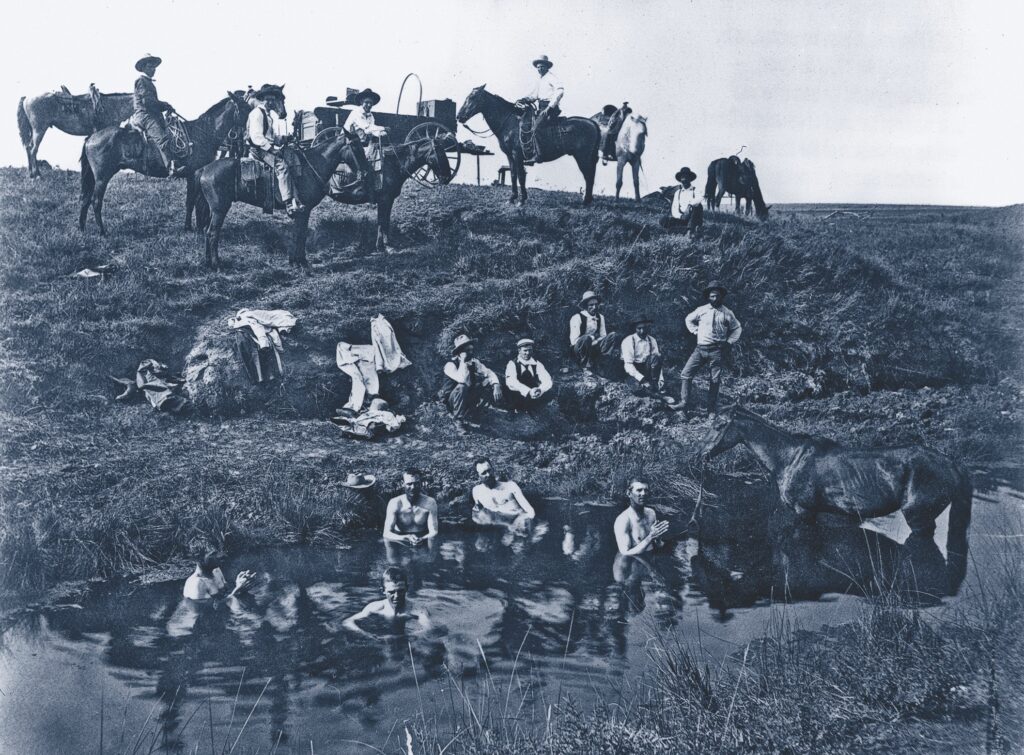

Cowboy Bath

Cowboys bathing in a pond, Seward County, Kansas, by F.M. Steele: Proof that cowboys did take off their hats.

—Johnny D. Boggs

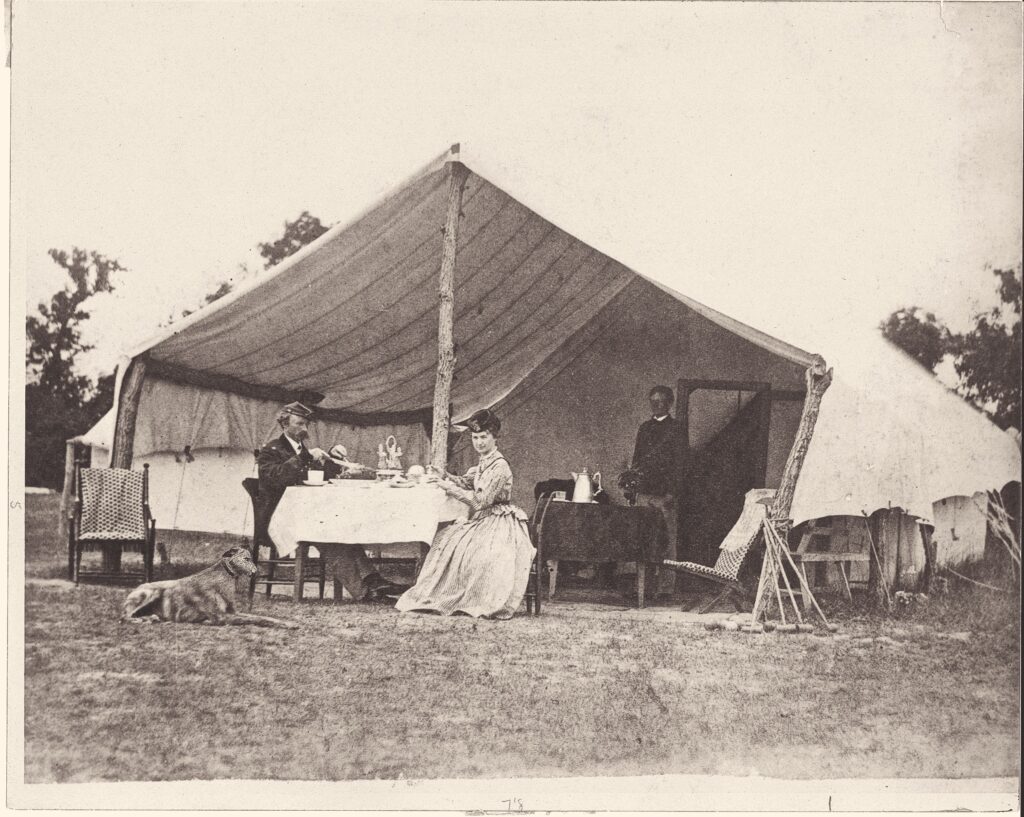

The Custers on the Prairie

Custer served Libbie some lunch on the Kansas prairie with a dog lying on the ground and a sentry standing nearby. And leaning up against the tent is a croquet set. They were humans, too.

—Thom Ross

Courtesy LIBI, NPS.gov

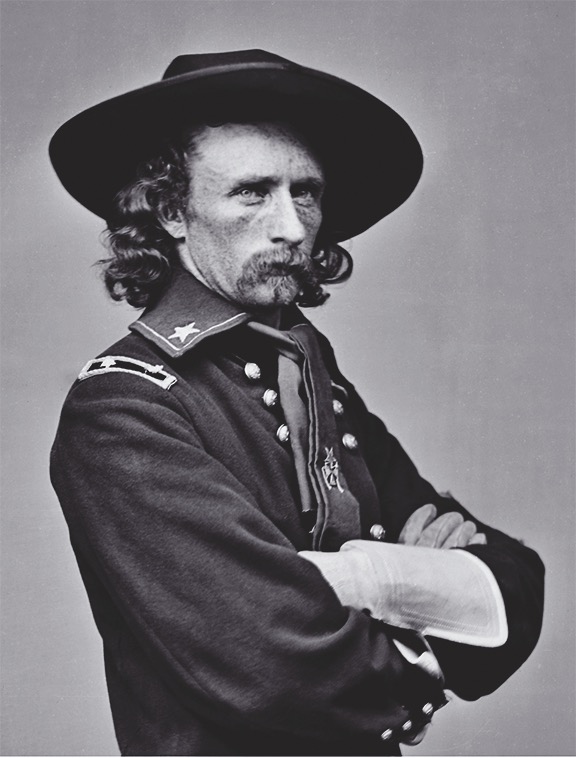

George Armstrong Custer

For me it has to be the Civil War photo of George Armstrong Custer standing, almost in profile, his arms crossed across his chest, his face looking at you with all that long hair and mustache… And he is what, 22 years old? The camera captures that feeling that no matter what happens, this kid is destined for Valhalla; and he made it!

—Thom Ross

Courtesy Library of Congress

So damn cocksure, it adds to the pathos. To me it’s like Babe Ruth pointing to the bleachers before the pitch. It isn’t bragging if you can pull it off.

—Bob Boze Bell

The Long Black Veil

There are many photographs of Elizabeth Bacon Custer in mourning dress after the death of her beloved Armstrong at the Battle of Little Bighorn, but an 1864 wartime image of a younger, newly wedded Libbie veiled in black while her husband fights in the bloody campaigns of Virginia is prophetic of a life of widowhood she is yet to fully understand.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Courtesy LIBI, NPS.gov

The Kid

Billy the Kid in front of Beaver Smith’s saloon. For a person of such ever-lasting mythic power THIS is all we have? Stupid hat, the blank expression, the awkwardness of the photographer’s stand…..THIS is Billy the Kid?? It sure the Hell is!

—Thom Ross

The ONE image of the Old West that still resonates with me…was there ever any doubt?

Can you imagine if we DIDNT have this one verified photo of the little scamp?

—James B. Mills

The most iconic, universally recognized photo in the entire Old West. How did this boy become the man that virtually everyone in the civilized world recognizes? What were his real joys? Heartaches? Ambitions? What girl did he really love? Will we ever have another photo of him, with provenance? What might he have become had he not been killed by Pat Garrett? Would he leave New Mexico, go straight or just go on being Billy? So many questions, so few answers.

—Roy B. Young

Billy the Kid: Love: the only documented photo of a favorite outlaw. Hate: a $2-plus million sale price that led to myriad…ahem…“Billy” photo discoveries.

—Johnny D. Boggs

I have spent way too much time looking at this crappy photograph. One of my historian friends quipped that studying the image is like looking at enraged mud turtles. So much noise, so little clarity. And, besides, the hat is totally wrong, his jaw is unhinged (a bend in the tin at that point doesn’t help) and his sweater is two sizes too big. How could such a bad photo be so good? Beats me, but I do love it in spite of all the flaws. Here’s looking at you, Kid.

—Bob Boze Bell

The most famous Old West shot of them all. Billy the Kid at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, in 1880,

the only known photo of the desperado. A tintype, the image is reversed but still gives us a

good idea of what the Kid looked like.

—Mark Boardman

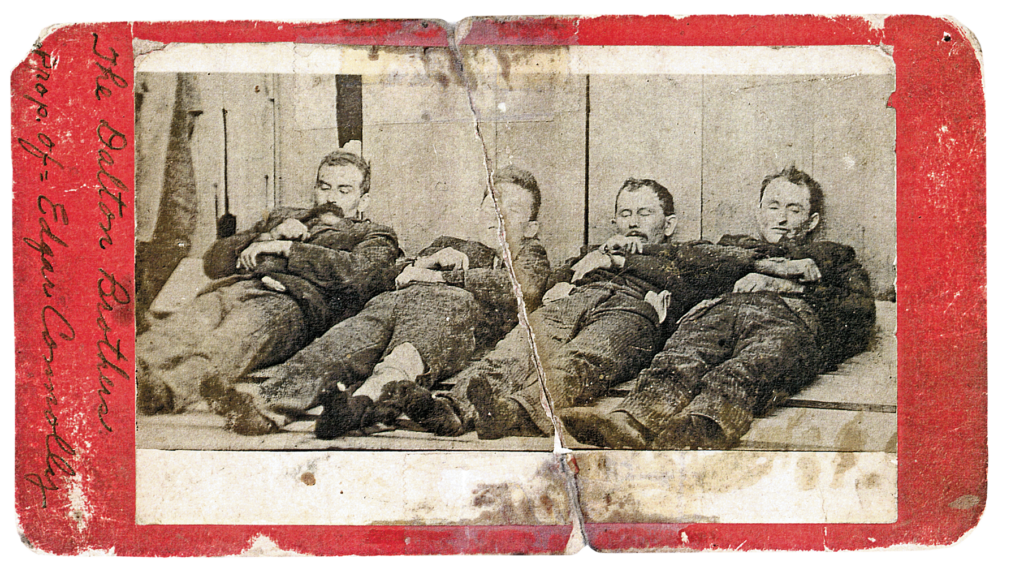

Death on Display

Along with the dead Daltons after the failed Coffeyville Raid there is that kid peering at the camera from the hole in the fence; this is NOT child abuse! This is a fabulous photo of grim death being watched over by a child.

—Thom Ross

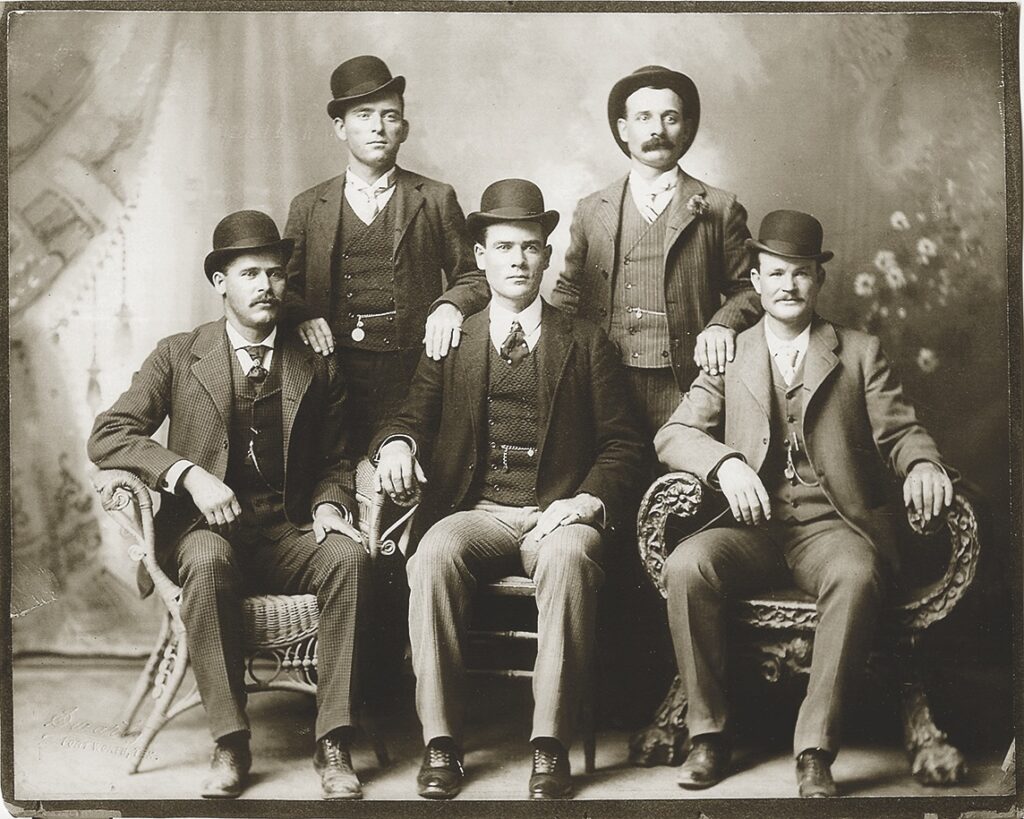

The Wild Bunch in Fort Worth, Texas

The grin on Butch’s face (sitting, far right) says a lot about who he may have been…a kind of happy-go-lucky, free-as-a-bird character; and then all the smiles end in grim death; not even their fancy suits could save any of them.

—Thom Ross

The Last Hurrah

A rare photo shows (l-r) the Sundance Kid, Etta Place and Butch Cassidy at their Argentinian ranch, ca 1903. For a time, they lived a peaceful life—until the Pinkertons came looking in 1905 and the outlaws moved out.

—Mark Boardman

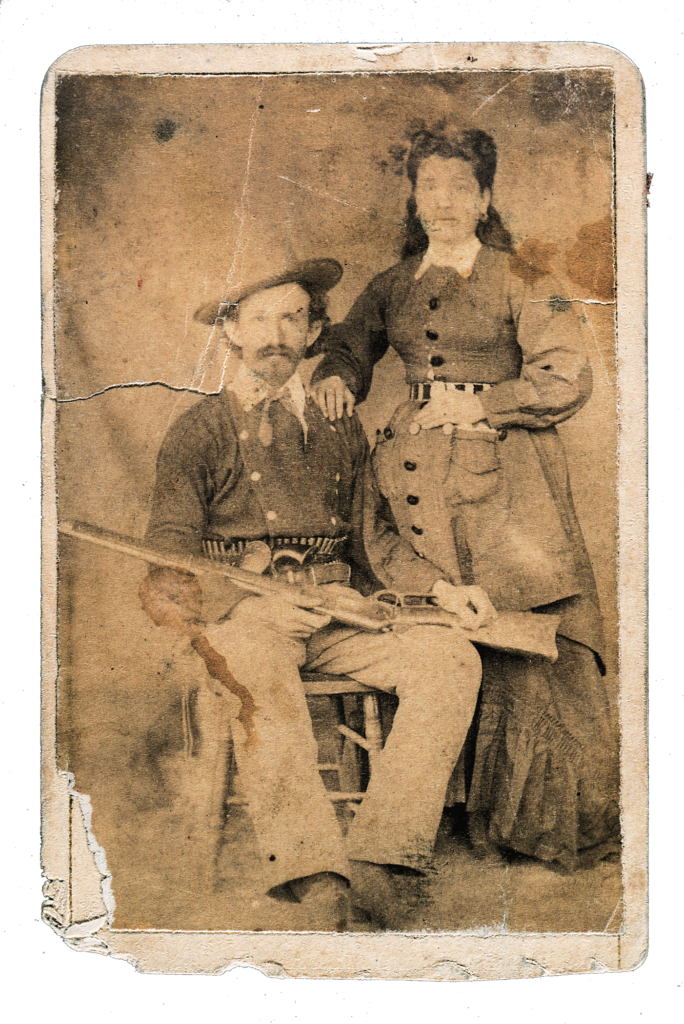

Bloodstained

Billy the Kid pal Charlie Bowdre and his wife, Manuela, sat for their portrait in Las Vegas, New Mexico, in 1878. Bowdre carried this copy when he was gunned down by Pat Garrett and posse in December 1880; those are believed to be his bloodstains.

—Mark Boardman

Lincoln, New Mexico, circa 1880s

In many respects, the town that Billy the Kid knew is still there,

a living history for visitors from around the world.

—Mark Boardman

Silver and Gold

The Tough Nut Mine, just outside of Tombstone, is shown in an 1880 photo taken by

Carleton Watkins. At about that time, the three investors—Ed and Al Schieffelin and

Dick Gird—sold their interests for a million dollars each.

—Mark Boardman

Courtesy Library of Congress

John Clum

The classic portrait of John Clum was taken by Dudley P. Flanders just after Clum arrived at the San Carlos Reservation in August 1874. Clum was the Forest Gump of his era, appearing first as an Apache agent at San Carlos (peacefully capturing Geronimo with his Apache police in 1877), and as publisher of the Tombstone Epitaph and mayor of Tombstone in the early 1880s. Clum left Arizona for Washington D.C. then in 1890 went to Alaska as a postal inspector and eventually Postmaster. Clum left Alaska in 1909 and traveled for the Southern Pacific Railroad lecturing on the West. This is one of my favorite images of John Clum for the importance of both the subject, and the photographer.

—Jeremy Rowe

Courtesy the Jeremy Rowe Collection

Navajo Woman with Child (Bosque Redondo, 1864-1868)

The harrowing expression on her face is a testament to the suffering her people were enduring there.

—James B. Mills

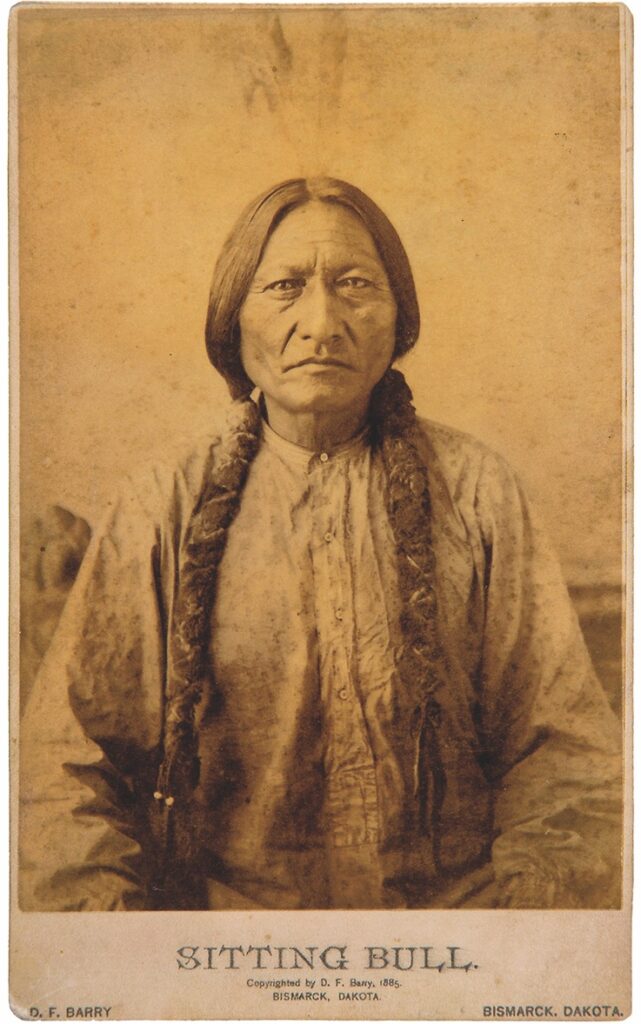

Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull…defiance…wisdom…leadership…in one photo.

—James B. Mills

Photo by D.F. Barry, True West Archives

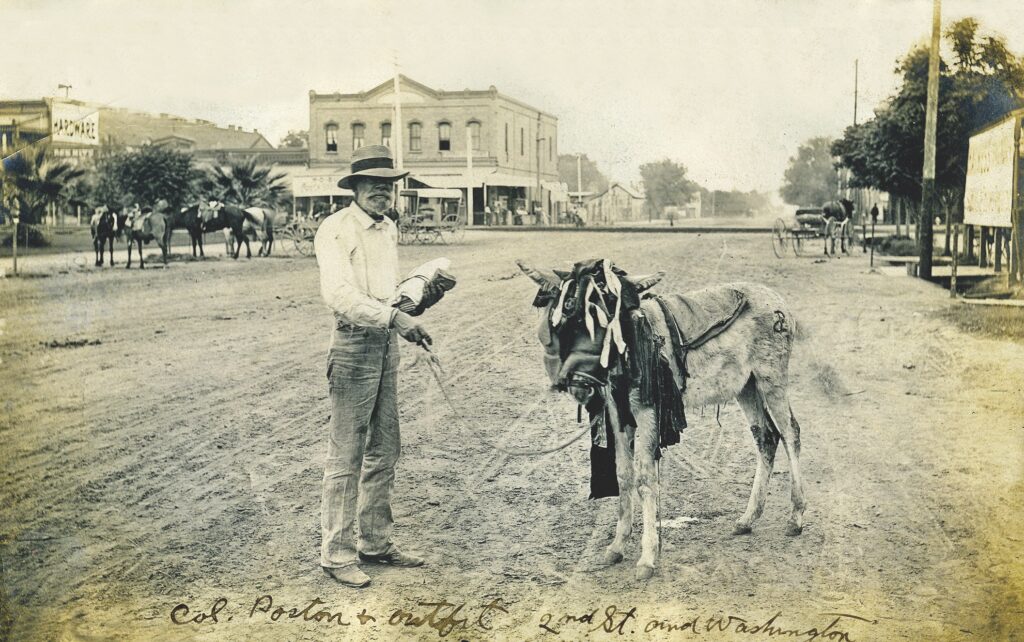

The Father of Arizona

Charles Debrille Poston (aka Colonel Poston), 1895-1902, was called the “Father of Arizona.” Poston was an explorer,

miner and the first delegate to the United States Congress from Arizona Territory in 1863. This portrait, circa 1898, shows the dramatic change as he went from wealthy miner and powerful politician to his final years as a pauper. Poston had become a fixture in Phoenix with his heavily decorated mule when the Arizona Legislature awarded him a $25 per month pension. Images of Western pioneers in their heyday have become iconic, but few document the other side of many of their lives.

—Jeremy Rowe

Courtesy the Jeremy Rowe Collection

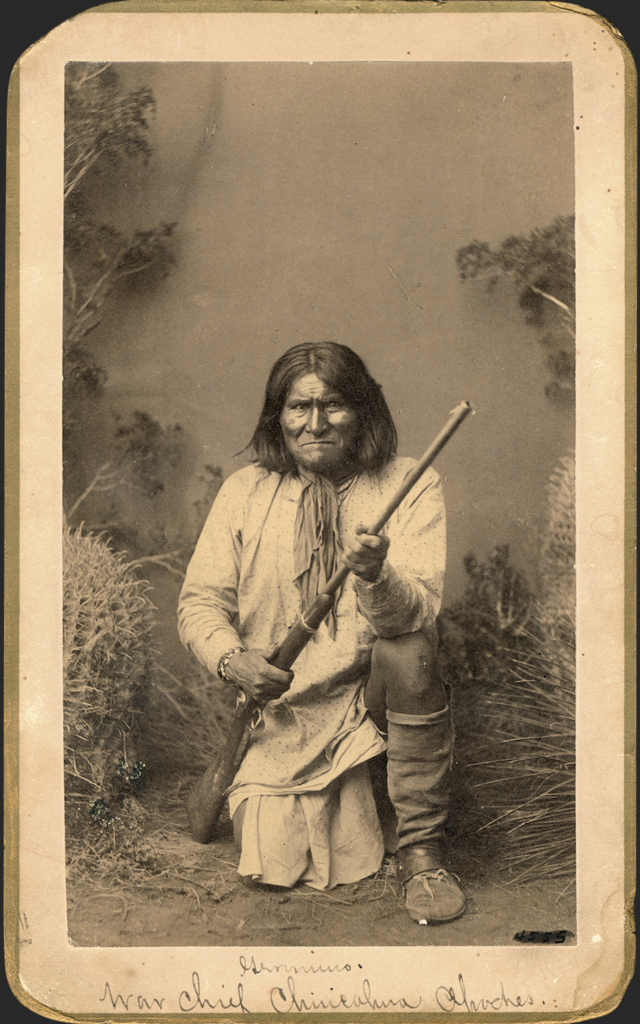

Geronimo Cabinet Card by A. Frank Randall, San Carlos Reservation, Arizona Territory, 1884

This is the earliest known photo of Geronimo, which C.L. Sonnichsen captioned “the face that launched a hundred articles, stories, and novels.” Within the last couple years it has come out that Chato, one of Geronimo’s mortal enemies is seen posing with the same rifle, the same scarf in the same location, begging the question, what exactly was the real Geronimo and what were studio props?

—Bob Boze Bell

Belle Starr and Friend

This is a new find and it’s got historians excited because some think the woman on the left could be the notorious Belle Starr. The face looks good, the hat is her style. What do you think?

—Bob Boze Bell

Courtesy the Dain Calvin Collection

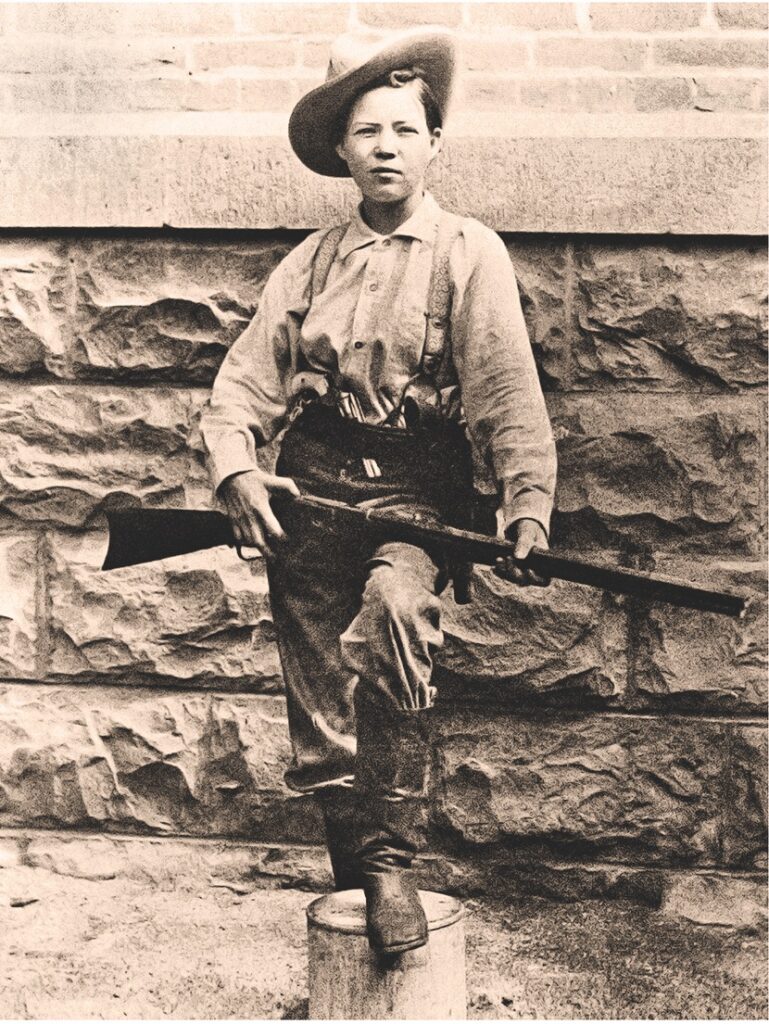

Pearl Hart with Rifle

Such a great image and to think it was taken at the Yuma Territorial Prison makes it even sweeter.

—Bob Boze Bell

I love the rifle-toting pic of Pearl Hart in the “bandit” outfit she wore when she robbed the stage to Globe in 1889. She needed suspenders to hold up the pants; her boots were way too big, and if she hadn’t cocked her dirty white hat, it would have covered her eyes. This is the “tough” photo of her that captured the nation. I also like the “sweet” picture of her that ran in newspapers back East. She’s seated with her hands demurely holding a small hankie, wearing a hat with flowers, a patterned blouse and an embroidered skirt. She looks just like the headlines: “A Beauty but a Bandit” and “Petite and Pretty, but Full of Nerve.”

—Jana Bommersbach

Calamity Jane

This is one of the finest photos of Calamity Jane, taken before she was debauched. She cuts a fine figure, and you can see how attractive she was in the beginning. Love it.

—Bob Boze Bell

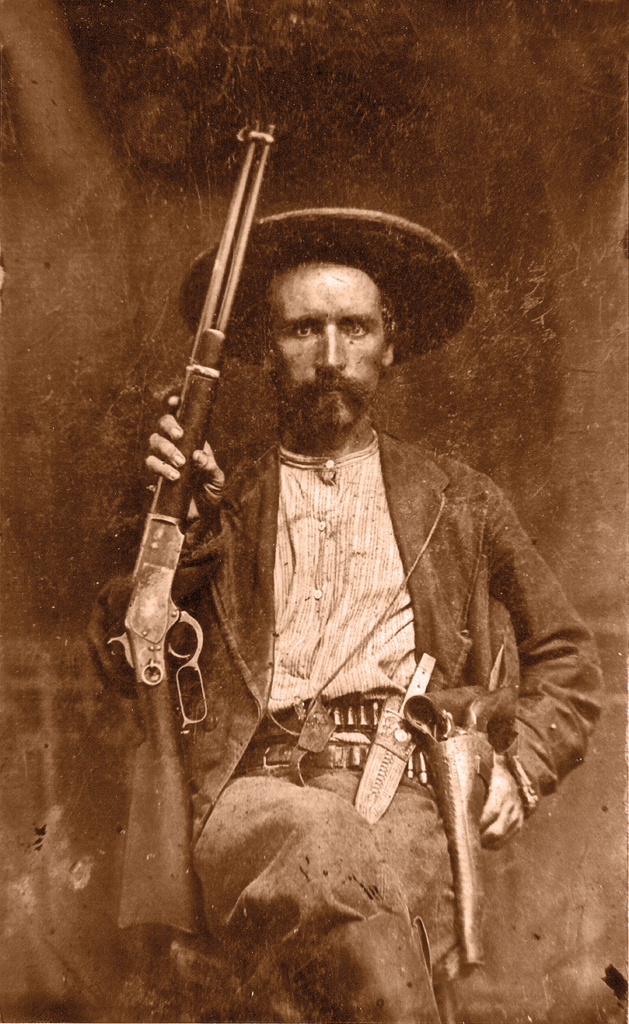

New Mexico Rustlers Cabinet Card, photographer and place unknown, circa 1880

Several historians think the standing man is John Kinney, leader of a large gang of rustlers in Southern New Mexico. I love this image because the guys look so hard and devious. One of my favorite shots of New Mexican bad boys.

—Bob Boze Bell

Loaded for Bear

Emblematic of the men who have served in the Texas Rangers the past 200 years, James B. “Jim” Hawkins was an original member of the Rangers’ Company D.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Courtesy Chuck Parsons

Kit Carson

The beaver hat (an ironic touch since it was that poor critter being made into headgear that first made Carson famous—sort of like Crockett’s coonskin cap) may well be from an incident in June 1854 when Carson was scouting for Major James Carleton against the Jicarilla Apaches. Carson was on a hot trail and assured Carleton that they would locate the Jicarilla camp by two o’clock the next day. Carleton, who at the time felt Carson’s reputation to be highly exaggerated, sniffed that if that indeed happened he would purchase Carson a fine beaver hat from New York. Precisely at two o’clock the next day the Indian village was located. Carleton became a believer and in his report of the action praised Carson as “justly celebrated as being the best tracker among white men in the world.”

Several weeks later a hat box arrived from New York at

Carson’s Taos home. The inside band of the fine beaver hat

was inscribed “At 2 o’clock—Kit Carson—from Major Carleton.”

—Paul Andrew Hutton

From “The Jayhawkers of ‘49,” John Colton Collection,

Courtesy Huntington Digital Library

Mickey Free

The enigmatic, one-eyed captivo cuts a fine figure in this early photo of Mickey Free. I still think there is a movie to be made about him.

—Bob Boze Bell

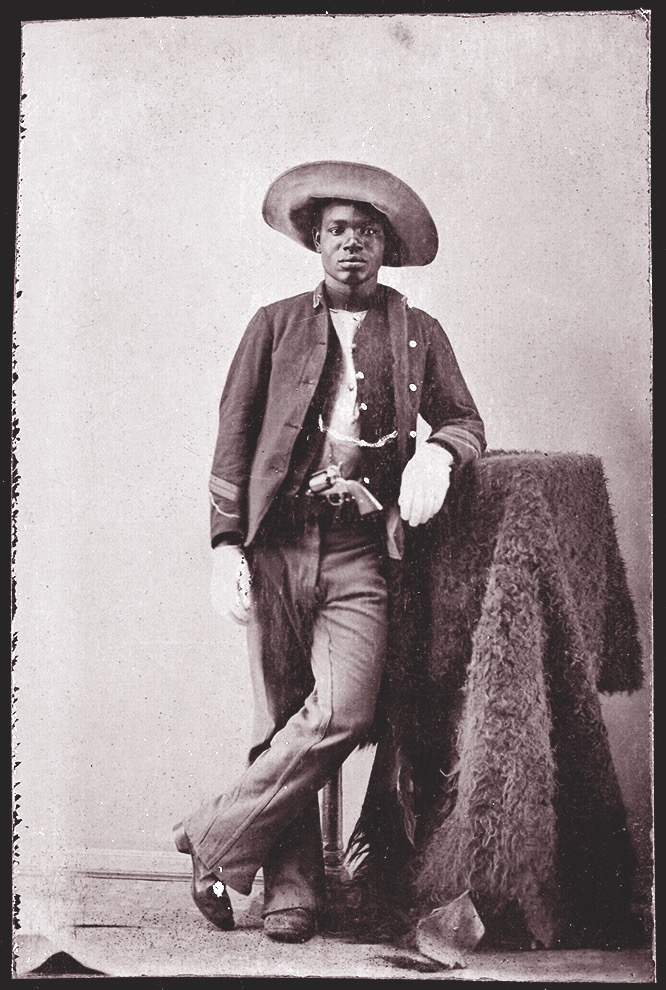

Buffalo Soldier

After the Civil War, thousands of free Blacks and former slaves such as this unknown man, enlisted in the U.S. Army and were sent West as part of six newly formed all-Black regiments, where they earned the nickname Buffalo Soldiers.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University

Ghost Dance, 1891

This has always been one of my very favorite photographs because of its age and because of what it represents. Here is a culture at its wit’s end, dancing to make White people disappear.

—Robert Ray