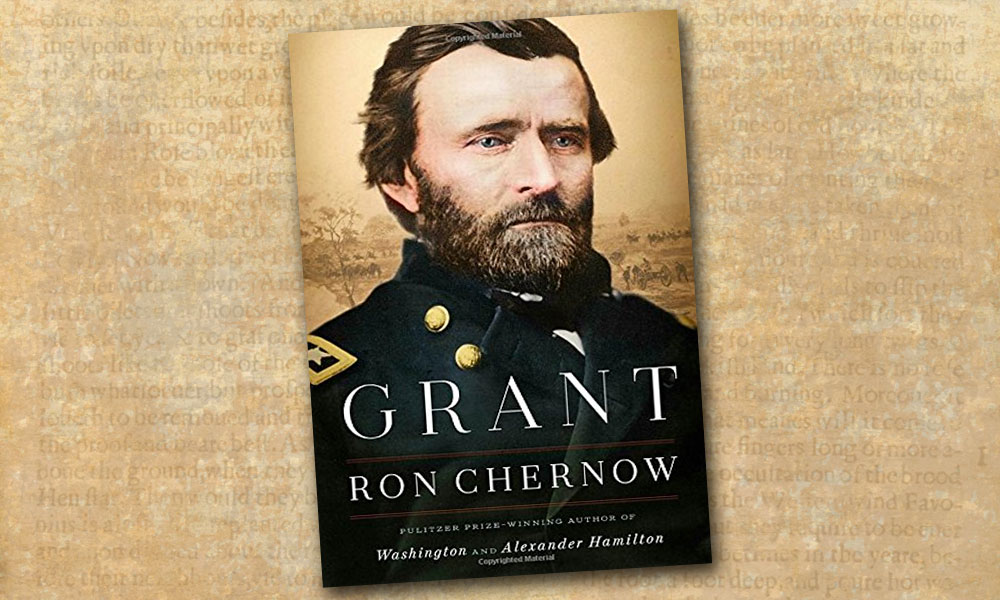

A century and a half ago, Civil War hero General Ulysses S. Grant was fated to become the Republican nominee for president of the United States. Grant was respected for his wartime leadership and post-war leadership of the Army. In 1868, the nation was in the midst of deep political, sectional and regional divisions over President Andrew Johnson’s administration, Reconstruction and the Western Indian Wars. Similar to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952, Grant was nominated on his superb record as a military man, but a novice to the politics of Washington, D.C. A Midwesterner like Ike, Grant won the office in a year of political and racial turmoil and unresolved wars. His subsequent two terms as president, from 1869-1877, would be the longest for a Republican until the man from Abilene served from 1953-1961.

Ron Chernow’s Grant (Penguin Press, $40) succinctly challenges a century-and-a-half of character stereotypes and misguided conclusions—many political or regionally biased—that Grant was the right man for the presidency, albeit with all the flaws of a man who struggles with the disease of alcoholism. “While drinking almost never interfered with his official duties, it haunted his official duties, it haunted his career and trailed him everywhere, an infuriating, ever-present ghost he could not shake,” Chernow writes. “It influenced how people perceived him and deserves close attention. As with so many problems in his life, Grant managed to attain mastery over alcohol in the long haul, a feat as impressive as any of his wartime victories.”

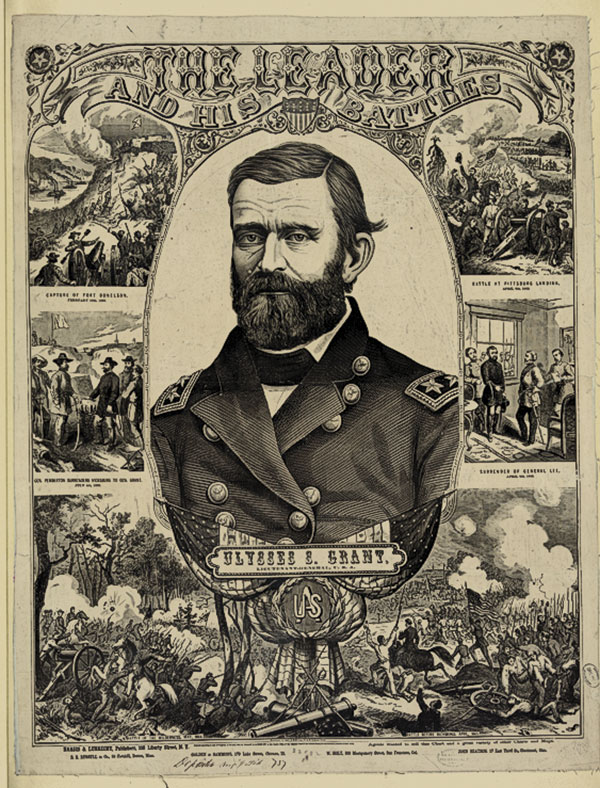

— Lithograph and Photo Courtesy Library of Congress —

With Grant, Chernow has published seven major biography/histories, including Washington: A Life, Alexander Hamilton and The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. The Brooklyn, New York, author has established himself as the greatest living American biographer. If his prior six books were not proof enough, Grant should be considered his finest effort. He is an empathetic and fair author, who has sought a deeper understanding of Grant’s flaws and strengths—as well as his loves and sorrows—with equal vigor. Throughout the biography Chernow also confronts 150 years of stereotypes in the historiography and scholarship that has slowly diminished the legacy of the Midwestern man raised in a temperate, abolitionist family home on the edge of Ohio frontier.

Chernow focuses much of his research and prose on the wartime years, 1861-1865, and Grant’s presidency, but like fellow Pulitzer Prize-winner T.J. Stiles’ recent biography Custer’s Trials, Grant deftly demonstrates how Grant’s egalitarian youth and military service in the West—before and after the Civil War—influenced his style of leadership, misunderstood by so many. “He…always led by the force of personality, not by gold braid and ribbons,” Chernow wrote about Grant.

Grant is more than 1,000 pages long with scholarly endnotes, bibliography and index, but Chernow’s style does not lag; it paces the reader forward with dramatic intrigue. The historian masterfully reveals that Grant’s life is equally common as it is noble. A scholar drawn to the drama of leadership and power, ambition and intellectualism, Chernow brilliantly reminds the reader of the humanity of the man who was raised in a modest, middle-class, Midwestern, Methodist home, only to become one of America’s greatest generals and one of the nation’s most overlooked and underrated presidents. As Grant’s good friend Mark Twain wrote, “All I care to know is that a man is a human being—that is enough for me; he can’t be any worse.”

—Stuart Rosebrook