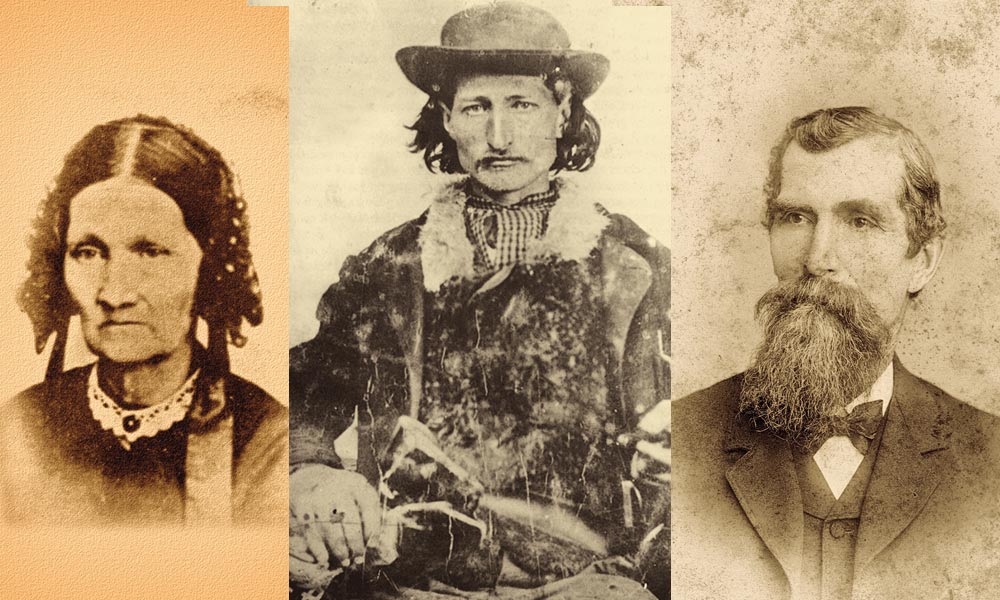

– Polly Butler, True West Archives; Wild Bill, National Archives, Washington, D.C., Photograph Courtesy Ethel Hickok; Lorenzo Hickok courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

Late afternoon finds me on the square in Springfield, Missouri, seeking the spot where Wild Bill Hickok gunned down Dave Tutt in that classic gunfight.

I mean, would I—or Louis L’Amour or any Western novelist—have enjoyed any semblance of a career, had not these two gunmen met here in 1865?

For years, I’ve wondered how it happened: Tutt, between College and Boonville…and Hickok, cattycorner away between South and St. Louis…separated by an estimated 100 paces—say, 80 yards—drawing their revolvers and firing simultaneously, Hickok unscathed and Tutt falling dead near the courthouse with a slug in his heart.

Eighty yards. That’s exceptional marksmanship with a revolver, especially in 1865.

Yet now, as I hurriedly find the marker that identifies where Tutt died, I understand. Wild Bill’s bullet didn’t kill Tutt. A rush-hour car must have hit the fool.

Didn’t your parents warn you not to play in the street!?!?!

Springfield made Wild Bill Hickok famous, but perhaps not because of a dead man named Tutt. It was also here in 1865 that Hickok agreed to an interview with Col. George Ward Nichols, who went on to write an article about Wild Bill that Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published 150 years ago in February 1867.

From then on, Wild Bill enjoyed celebrity status until he was killed in 1876—a good career move, seeing how it rocketed the Illinois native into immortal legend. But

he had lived a pretty eventful life even before he talked to a pseudo-journalist

in Springfield.

Land of Lincoln

Before he became Wild Bill/Dutch Bill/Duck Bill/Shanghai Bill, he was James Butler Hickok, born on Saturday, May 27, 1837, in Homer, Illinois. Homer eventually became Troy Grove, and it’s here you’ll find the Wild Bill Hickok Memorial, a state historic site. Although Wild Bill’s childhood home is long gone, the nearby Mendota Museum & Historical Society displays a scale model of the house.

– Map and Photo Courtesy Library of Congress –

His father was a diehard abolitionist, and legend has it that Wild Bill helped his father with the Underground Railroad. But the kid dreamed more of following in the footsteps of Daniel Boone and Kit Carson. Kansas Territory appealed to him. By 1854, two years after his father’s death, Wild Bill found work in Utica/North Utica, Illinois, driving a wagon for the Illinois and Michigan Canal. When his boss mistreated his team, Hickok did what most employees only dream of doing: He tossed the SOB into the canal.

Kansas Days

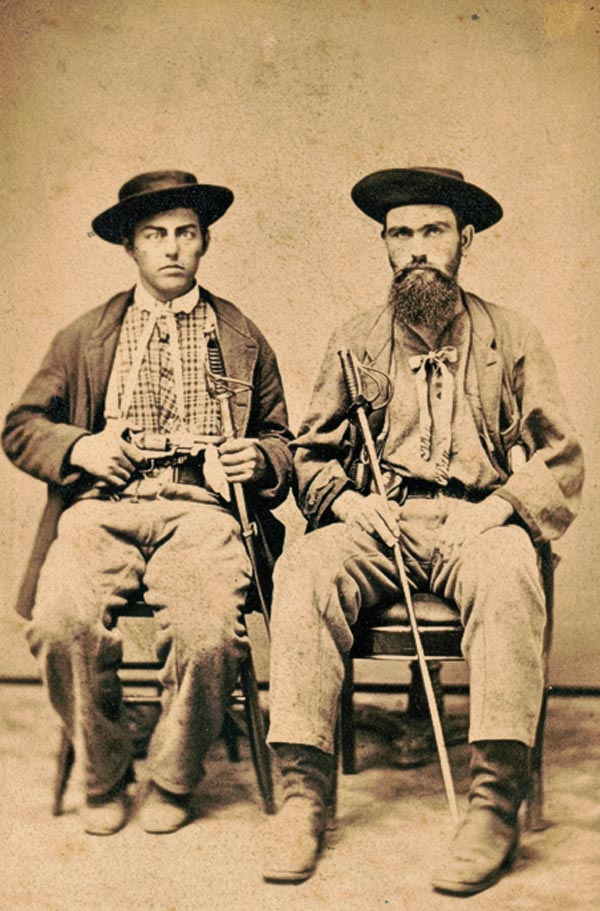

Two years later, Wild Bill and his brother, Lorenzo, set out for Kansas to farm and likely help in the Free State Movement. The Monticello Community Historical Society, headquartered at Floyd Cline Hall in Shawnee, has identified the Hickok land claim as being located at 8649 Clare Road in Lenexa. I’ll take their word for it. Suburban KC looks pretty much the same.

Wild Bill reputedly joined James Lane’s Free State Army, and he was popular enough to be elected constable of Monticello Township in 1858. Before long, though, Wild Bill headed to Leavenworth and took a job as a teamster for Russell, Majors and Waddell—and met a lifelong friend, a young lad named William Cody. Wild Bill reportedly even spent the fall and winter of 1859 at the Cody home in Leavenworth.

With Russell, Majors and Waddell

By 1860, both Wild Bill and the future Buffalo Bill would be riding hell-bent-for-leather with the Pony Express. It must be true. Because I’ve seen the 1953 movie Pony Express, which has one of my all-time favorite Western movie dialogue exchanges.

Wild Bill (Forrest Tucker):

Well, I’m sure glad we’re not arriving here tomorrow.

Buffalo Bill (Charlton Heston): Why?

Wild Bill: ’Cause there ain’t gonna be no whiskey here tomorrow.

On April 3, 1860, the first rider rode away from Pikes Peak Stables in St. Joseph, Missouri—now the Pony Express National Museum. That rider wasn’t Buffalo Bill or Wild Bill. Wild Bill stuck to coaches and freight wagons, and there’s doubt regarding Cody’s legitimacy as a Pony Express rider.

The Pony Express National Museum (above) is housed in the restored Pikes Peak Stables, aka the Pony Express Stables, in St. Joseph, Missouri.

– Courtesy St. Joseph, MO Vistors Bureau –

If we believe the legend, Hickok met up with Jack Slade after Indians ran off with livestock at Plant’s Station in Wyoming. And Hickok led the party that went out on a successful mission to get those animals back.

We can also believe that, at some point, Hickok got into a row with a bear, and that’s what sent him to Nebraska to recover.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Rock Creek Station

Originally Weyth Creek, Rock Creek had been a camping spot on the Oregon Trail. The Pony Express rented the station from David McCanles. The Express wasn’t making money. McCanles wanted to get paid. That’s what, allegedly, brought him to Rock Creek Station—now restored as a state historical park—on July 12, 1861.

Colonel Nichols’s report has Hickok calling McCanles “the Captain of a gang of desperadoes, horse thieves, murderers, regular cut-throats…” and that Hickok defeated ten of those ruffians.

Pony Express station in 1857, Rock Creek is now a 350-acre Nebraska state historical park.

– Courtesy Nebraska Tourism –

All we know for certain is that three men—McCanles and two employees, James Woods and James Gordon—died, but who killed who is debated. I like the story that Jane Wellman, common-law wife of station keeper Horace Wellman, killed Woods with a hoe. In any event, Hickok, Horace Wellman and Pony Express rider James W. “Doc” Brink were brought to trial. The defendants said they acted in self-defense. The judge agreed and dropped the case. Hickok decided he had healed and left Nebraska.

Civil War Adventures

Back in Leavenworth, Hickok enlisted in the Union Army as a scout. We know he served as a wagon master in Sedalia, Missouri, and that he wound up in Independence, Missouri, where a woman shouted to him, “Good for you, Wild Bill.”

He didn’t object. I mean, it had to be better than Duck Bill (a moniker given him because of the shape of his nose).

(Aside: There’s also a great story that, after the war, Hickok umpired a baseball game in Kansas City. Most historians debunk it, but while you’re in the KC area, visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Wild Bill would appreciate it. He was, after all, an abolitionist.)

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

By March 1862, Wild Bill claimed he was scouting for Union Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, where Hickok took part in the Union victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in northwestern Arkansas.

After bossing wagons, fighting Rebels and spying for the Union (including, the story goes, at the Battle of Westport outside of Kansas City), Wild Bill moved to police work. That’s what he was doing in Springfield, Missouri, in 1864.

Springfield and Legend

Hickok worked as a detective in Springfield, scouted for Gen. John B. Sanborn, and was mustered out of the Army in June 1865.

In Springfield, he sat down for a friendly game of poker with Dave Tutt. It didn’t turn out to be that friendly, perhaps because of a woman, definitely because of a watch. Tutt took Wild Bill’s Waltham repeater as collateral over a $25 poker debt. Wild Bill told Tutt not to show off his watch.

At 6 p.m. on July 21, both men found themselves on the Springfield town square in an honest-to-goodness walk-down gunfight. Hickok was later acquitted of a manslaughter charge.

– Photos by Johnny D. Boggs –

Then, Wild Bill met author George Nichols and the rest is history. Of course, it took two years before the article was published. With that much time, you’d think Nichols and his editors might have gotten more facts right. But then, we might not have Joseph G. Rosa’s biographies of Hickok, Gary Cooper’s The Plainsman or countless shootouts on Gunsmoke and thousands of films, TV shows and novels.

As James D. McLaird writes in Wild Bill Hickok & Calamity Jane: “Despite having killed several men, Hickok was relatively unknown before the Harper’s article. Afterwards, he was a celebrity. Bystanders pointed him out on the streets; eastern visitors sought interviews with him; and newspapers throughout the country reported his presence as he passed through their communities.”

“Umpire Colt,” Johnny D. Boggs’s Wild Bill-baseball short story, appears in the Brett Cogburn-edited anthology, Showdown, from High Hill Press.