The Plains Indian women’s role in the buffalo hunt was no small thing. “Theirs was harder work than buffalo hunting,” explained John C. Ewers, in The Blackfeet.

“At the time of the ‘great fall hunt,’ there was no rest nor excuse for her. She must work at any and all hours,” wrote Col. Richard Irving Dodge, in his 1882 book, Our Wild Indians. “If the herds were moving, the success of the hunt might depend on the rapidity with which the women performed their work on a batch of dead buffalo. These animals spoil quickly if not disembowelled, and though the hunters tried to regulate the daily kill by the ability of squaws to ‘clean up’ after them, they could not, in the nature of things, always do so.”

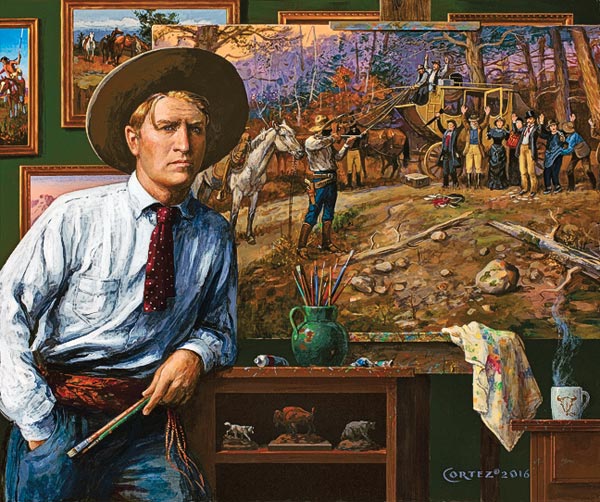

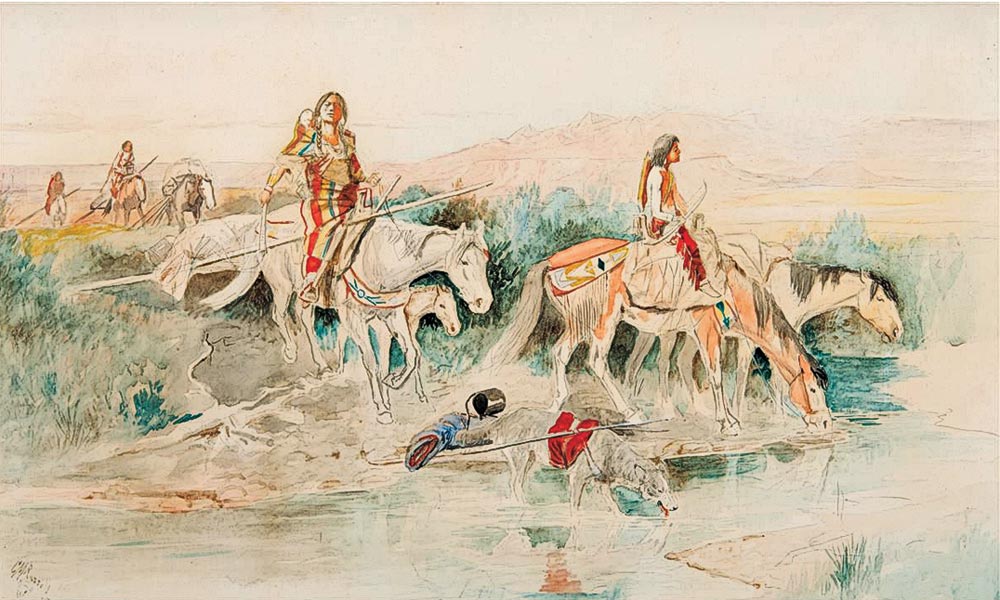

The central matriarchal figure, who labors forward with her child on her back, all while managing her heavily laden travois, is Charles M. Russell’s circa 1894 testament to these hard and fast workers. Following the Buffalo Run hammered down at $1.1 million, as the top lot at the C.M. Russell Museum’s benefit auction in Great Falls, Montana, on March 18.

When hunting bands moved from one encampment to another, to follow the buffalo across open grasslands, the men traveled light, carrying only their weapons, ever ready to defend their families. The women shouldered the burden of transporting the family lodge, furnishings and utensils. The heaviest, the tipi, weighing an average 75 pounds, dragged on the A-shaped travois.

When the time came to dress a buffalo hide, a woman had an arduous task in front of her. After removing the hide from the dead animal, she stretched it on the ground, hair side down, and drove lodge pegs through to hold it in place, as she hacked away tissue and fat with a sharp tool. After days of the sun curing and bleaching the hide, she scraped the inner surface to even it out. After rubbing the hide with an oily mixture of buffalo brains and liver, leaving it out in the sun to dry again, and finally softening the skin by rubbing it with a rough stone, the buffalo robe was ready for market.

Russell’s equal treatment of men and women in his artwork resulted in this accomplished work that proves the adage true: “A woman’s work is never done.”